Round arches carried by columns in the with Doric order reflect classicizing trends in the former Franciscan convento of Tecali de Herrera, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Luis Espinoza, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Renaissance — not just in Italy

The term “renaissance” generally invokes images of Italian cities, buildings, and artworks, rather than images of American ones. However, the renaissance had tremendous repercussions on the American continents, and its influence can be found from Philadelphia to Buenos Aires. In fact it might be more useful to think of the renaissance not as a European phenomenon at all, but as a wide-ranging cultural movement that centered on the rebirth and rediscovery of classical (ancient Greek and Roman) culture that sparked many innovations and changes in architecture, urbanism, pictorial art, theatre, science, literature, and more.

Map of New Spain. Note that at its height, the Viceroyalty of New Spain also included Central America, parts of the West Indies, the southwestern and central United States, Florida, and the Philippines.

Cities, buildings, and architects in New Spain

Spanish colonizers and criollos believed that adopting specific classicizing architectural styles from Europe helped to give their civic and religious buildings a sense of proper decorum. The idea of what constituted decorous architecture derived from Greek and Roman philosophical and architectural sources, including those written by Aristotle, Cicero, St. Augustine, and even Isidore of Seville.

In the sixteenth century, cities were considered to embody an ideal of sophisticated and refined living. This is an ancient idea that took root among peoples in Spain during the medieval period. In the Hispanic world, the term for this idea of a civilized urban center was policía (which derives from the ancient Greek term polis, meaning city). This idea of the ordered urban center was brought to the Americas where the structure and building of cities became one of the most important colonizing strategies of the Spaniards.

One of the regions in the Americas that saw a resurgence of classical culture was Mexico. From the early sixteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, the territory roughly comprised by present-day Mexico, the midwestern and southwestern U.S., and parts of Central America was known as New Spain — a territory claimed and ruled by the Spanish Crown. Throughout this period, towns and cities in the central and southern part of New Spain (by far the most populated of the territory) grew in size. They were inhabited by a diverse population that included Spanish colonizers, criollos (the offspring of Spanish colonizers born in the Americas), Indigenous peoples of diverse ethnic origin, Africans (originally brought as slaves, many later becoming freed citizens), small communities of other Europeans, Asians, conversos (Jewish people who had been converted to Christianity), and many ethnic mixtures in between.

Cities acquired a prominent place in the colonizing strategies of the Spaniards. Spanish colonizers and criollos adopted architectural styles from Europe in an effort to validate their civic and religious institutions. Cities participated in dividing peoples along ethnic lines to create social and racial hierarchies. During the sixteenth century, cities were created for Indigenous peoples, while other cities were created for Spaniards and their offspring, in what was a clear effort to segregationist effort on behalf of the Spanish colonizers. Cities for Indigenous peoples were termed repúblicas de indios, while repúblicas de españoles was the term employed for cities destined for European colonizers and their offspring. In the repúblicas de españoles—and also in the república de indios, but arguably to a lesser extent—the preferred architectural language of the most representative buildings was classical in style.

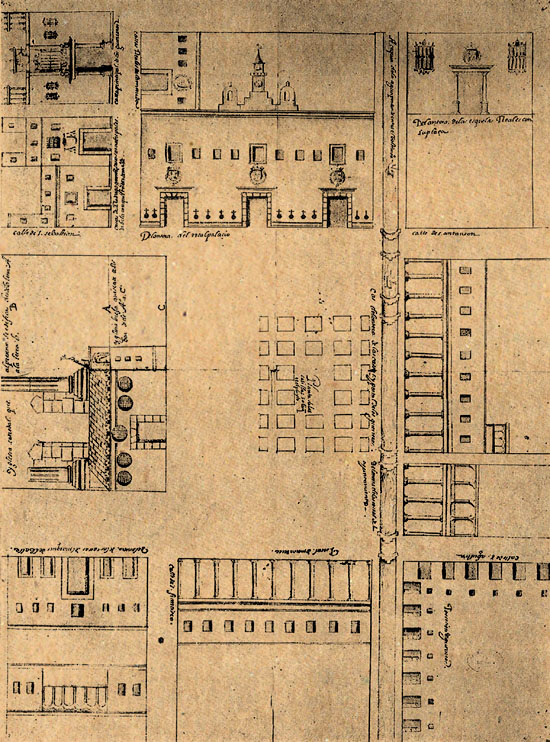

Residences for elite families or buildings such as city halls, educational institutions, and hospitals, drew from classical architectural sources. In a plan of Mexico City’s central square drawn in 1596, we can see that some of the most important buildings of the city had portals with classical elements such as columned porticoes. Mexico City at the time must have been (architecturally speaking) reminiscent of towns in the Iberian Peninsula (such as Trujillo or Cáceres, both in the region of Extremadura, the birthplace of conquerors and architects, like Francisco Becerra).

Episcopal Palace with classicizing details, Cáceres, Spain, 13th to the 17th century, with a renaissance façade (image: Horst Goertz, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Religious architecture, including cathedrals, monasteries, and church-sponsored buildings such as hospitals and orphanages, were also designed to employ the language of classical architecture—to indicate proper decorum and appropriateness.

Façade of the ex-convento of Tecali de Herrera, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Luis Espinoza, CC BY-NC 2.0)

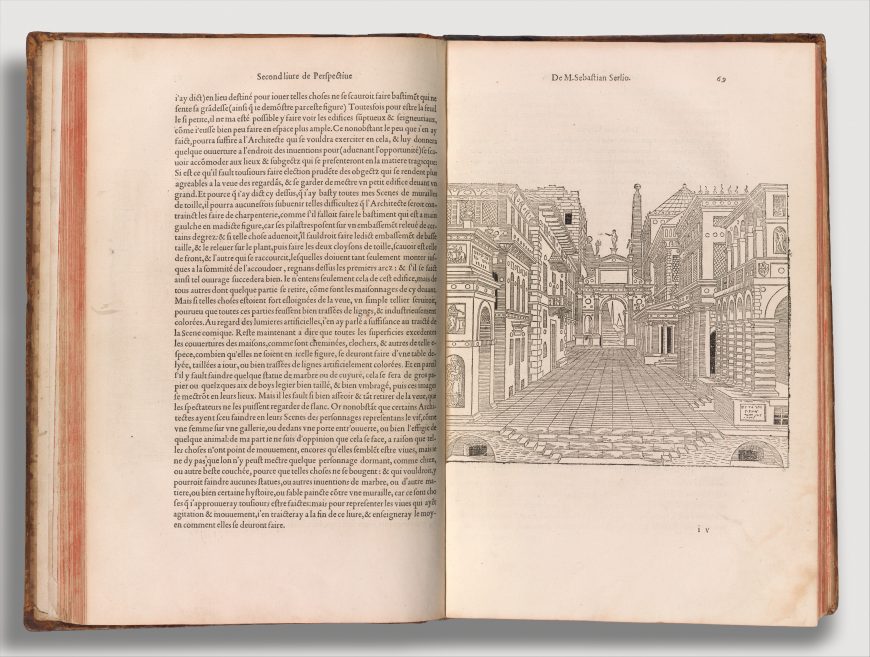

The façade of the Convento de Tecali is considered to be one of the most refined late-Renaissance designs in New Spain. Some elements, like the proportions of the architectural orders, were likely taken from a treatise like the one by Sebastiano Serlio, an Italian architect who published a profusely illustrated treatise in the 16th century, which was extremely influential in both Europe and the Spanish Americas.

Sebastiano Serlio, Book 2 of The Book of Architecture, published by Jean Barbé, 1544 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Architects, patrons, and their sources

Some of the first classically trained architects, like Claudio de Arciniega and Francisco Becerra who arrived in New Spain (from Spain) began practicing their trade during the latter part of the sixteenth century. Their presence signaled the arrival of late-Renaissance architecture to the viceroyalty.

The façade and portal of the Casa del Deán, the residence of the dean of the Cathedral Chapter of the City of Puebla, showcases the classicizing renaissance influences brought to New Spain. The design of this urban palace has been attributed to Becerra, an architect born in Extremadura, Spain. The dean, named Tomás de la Plaza, was known to be a humanist, a person who studied classical literature and culture, which explains his choice of the classical style for his residence.

Even prior to their arrival, the first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza (who ruled from 1535–1550), was well-versed in matters of architecture, and was known to have possessed copies of the architectural treatises by Vitruvius (the ancient Roman architect) and Leon Battista Alberti (the Renaissance architect). These treatises were the most important vehicles of transmission of classical architectural forms. We see the likely influence of these publications in the official architecture that was built during the sixteenth century in the viceroyalty, and the way cities such as Puebla and Mexico City were being designed and developed. For Europeans in New Spain, just as in Europe, these treatises represented the pinnacle of architectural theory; they were the accepted repository of knowledge regarding what classical architecture was, the knowledge needed to practice the discipline of architecture, and the manner of properly designing and constructing buildings and cities.

Façade of San Martín Huaquechula, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Thelmadatter, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Complicating Classicism

By the start of the seventeenth century, it appeared clear that the classical architectural tradition had taken root. At the same time, it was also clear that the Indigenous and mestizo builders who constituted the bulk of the work force in New Spain, had also established a style of their own. This was especially the case in towns and cities that were more distant from the repúblicas de españoles.

In reality, this architectural style had been there all along, as some of the first monasteries erected by the mendicant missionaries together with the native workers and builders, were fascinating architectural combinations of European influences—including Gothic, Mannerist, Plateresque, Mudéjar, and classicizing Italianate—combined with Indigenous traits and attributes.

Façade of San Martín Huaquechula (detail), 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

We see this in the façade of the Convento de Huaquechula, for instance, approximately 56 km (35 miles) south of the City of Puebla. It has a main portal of carved stone that displays native sculptural traits, such as floral designs in an Indigenous style, in which the stigmata are represented as a native motif of a bleeding wound (center of the image, on the spandrel within a coat of arms held by a cherub). The stigmata was a symbol employed by the Franciscan Order, reminiscent of their founder, St. Francis of Assisi, who received the stigmata. Today, this style has been called at times mestizo, other times hybrid, with no consensus among experts on a definitive term.

Baroque interior of the Church of Santa María Tonantzintla, Cholula, Puebla, Mexico, 18th century (photo: Photovicz, CC BY-SA-4.0)

Once the classical language of architecture took hold, it appeared to start its transformation into the next big architectural wave, which art historians often call the Baroque — which constituted the most developed and fascinating architectural tradition to flourish during the viceregal period in New Spain and other Spanish dominions in the Americas. It bears remembering, however, that Baroque architecture in New Spain and elsewhere borrowed elements from the classical language of architecture as a basis for articulating and ordering its own vocabulary.

Additional resources

Mission churches as theaters of conversion in New Spain

Aristotle, “Book IV,” in Nicomachean Ethics, The Internet Classics Archive

Carlos Chanfón Olmos, ed., Historia de la arquitectura y el urbanismo mexicanos: El periodo virreinal, Tomo I: El encuentro de dos universos culturales (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997).

Fernando Checa, Alfredo Morales J., and Víctor Nieto, Arquitectura del renacimiento en España, 1488–1599. Manuales de Arte (Madrid: Cátedra, 2009).

Luis Javier Cuesta Hernández, Arquitectura del Renacimiento en Nueva España: “Claudio de Arciniega, maestro maior de la obra de la Yglesia Catedral de esta ciudad de México” (Mexico City: Universidad Iberoamericana, 2009).

Federico Fernández Christlieb and Angel Julián García Zambrano, Territorialidad y paisaje en el altepetl del siglo XVI (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2006).

Yolanda Fernández Muñoz, “El arquitecto Francisco Becerra,” Boletín de Monumentos Históricos – Tercera época, no. 27 (April 2013), pp. 135–50.

Jonathan Israel, Raza, clases sociales y vida política en el México colonial, 1610–1670 (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1980).

Richard Kagan, Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).

John McAndrew and Manuel Toussaint, “Tecali, Zacatlan, and the Renacimiento Purista in Mexico,” The Art Bulletin vol. 24, no. 4 (1942), pp. 311–25.

Antonio Molero Sañudo, “Francisco Becerra y Otros Nuevos ‘Arquitectos’ En La Nueva España,” NORBA, Revista de Arte XXXVI (2016), pp. 69–94.

Ernesto de la Torre Villar, Las congregaciones de los pueblos de indios (Mexico City: UNAM, 1995).

Guillermo Tovar de Teresa, “La utopía del virrey de Mendoza,” in La utopía mexicana del siglo XVI: Lo bello, lo verdadero y lo bueno, 1st ed. (Mexico City: Editorial Azabache, 1992).