Tiwanaku, c. 800–1000 C.E., near Lake Titicaca, Bolivia (photo: Mhwater, in the public domain)

The Sacred Center of Tiwanaku

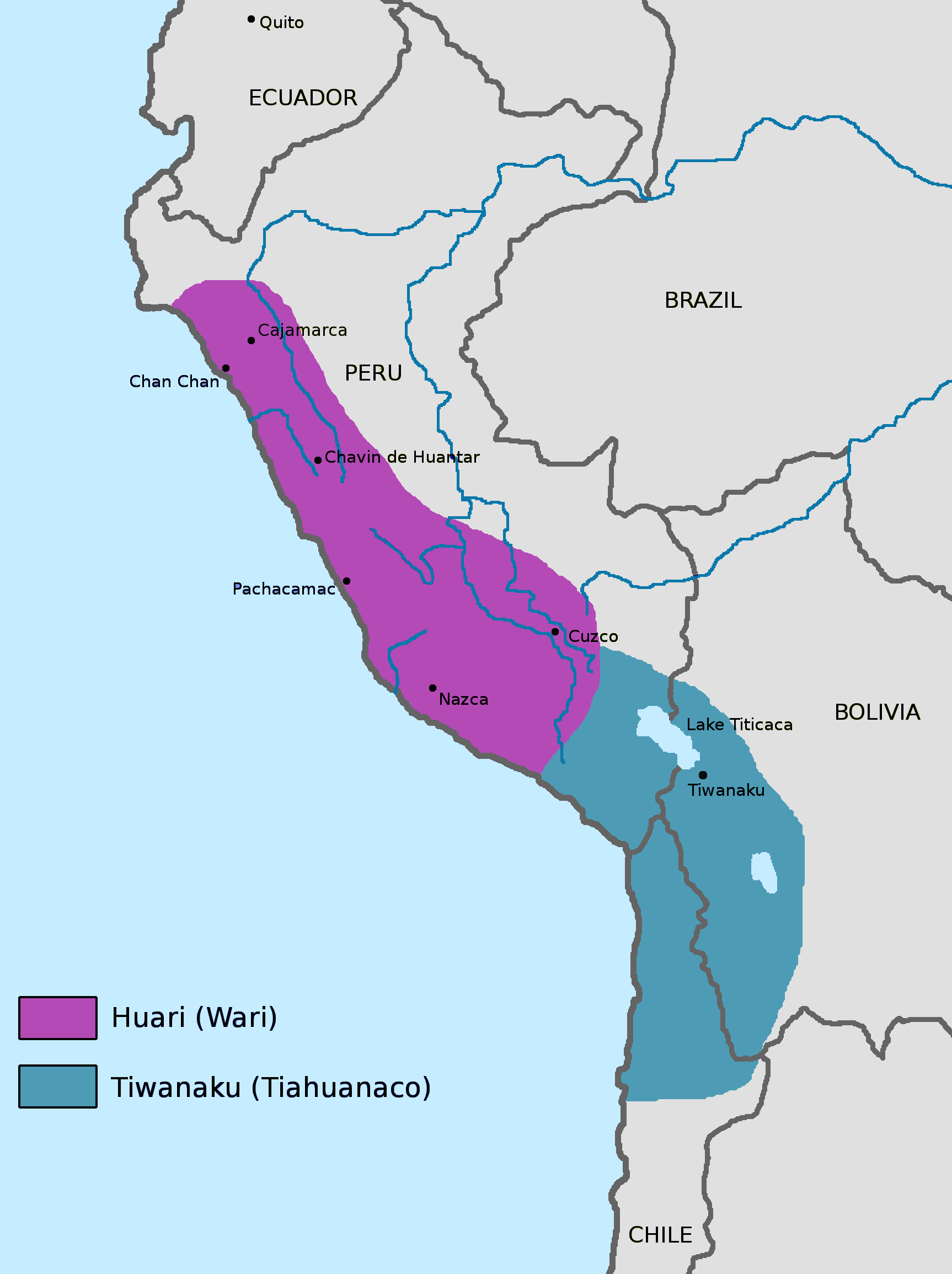

Map of Tiwanaku and Wari civilizations, South America. Wari civilization dates to the 6th–11th century, flourishing about the same time as Tiwanaku (image: Zenyu, in the public domain)

The north coast of Peru was not inactive after the fall of the Moche around 800 C.E. The Lambayeque and Chimú cultures that succeeded them built impressive monuments and cities. In fact, the Chimú civilization dominated nearly the entirety of the north coast of Peru for over 400 years until they were conquered by the Inka empire in 1470. Exciting cultural and artistic developments were also occurring in the highlands at around the same time that the Moche, Lambayeque, and Chimú cultures dominated the north coast.

The Tiwanaku civilization (200–1100 C.E.) was centered in the Lake Titicaca region of present-day southern Peru and western Bolivia, although its cultural influence spread into Bolivia and parts of Chile and Argentina. Tiwanaku’s main city center boasted a population of 25,000–40,000 at its peak, consisting of elites, farmers, llama herders, fishermen, and artisans. Its ceremonial center featured a tiered pyramid called the Akapana, and a temple complex (the Kalasasaya).

Gateway of the Sun

Sun Gate, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: Brent Barrett, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). View in Google Street View.

The people of Tiwanaku were skilled engineers and masons, producing impressive stone buildings and monuments. Perhaps one of the most iconic works of Tiwanaku public architecture is the Gateway of the Sun, a monolithic portal carved out of a single block of andesite. The monument was discovered in the city’s main courtyard and may have originally served as the portal to the Puma Punku, one of the city’s most important public shrines. The Gateway contains low relief carvings across the lintel set into a square grid. At the center of the lintel is Tiwanaku’s principal deity.

Sun Gate, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: Ian Carvell, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

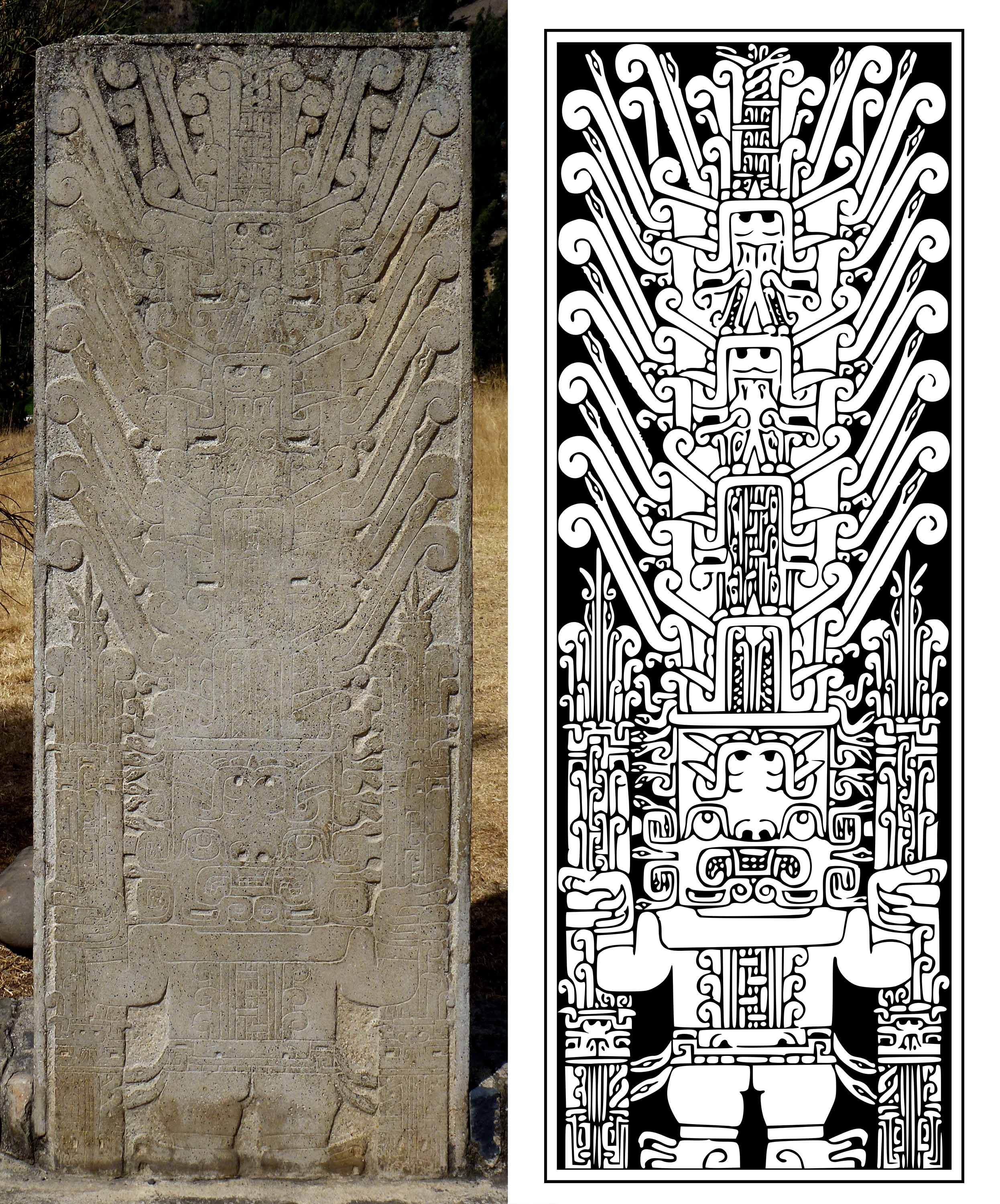

Left: the Raimondi Stele, c. 900-200 B.C.E., Chavín culture, Peru (Museo Nacional de Arqueología Antropología e Historia del Peru, photo: Taco Witte, CC BY 2.0). Right: Line drawing of the Raimondi Stele (source: Tomato356, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The figure is faced frontally, holding two implements terminating in bird heads, perhaps representing a spearthrower and spears. He wears an elaborate tunic decorated with human and animal faces. The eyes of the figure bear the characteristic Tiwanaku stylized teardrop—a winged feline that hangs down from the eye to the bottom of the face. Tendrils of hair emanate in rays from the head, terminating in feline heads and circles. Composite human-bird deities flank the central figure on both sides.

As many scholars have pointed out, the deity represented on the Gateway exhibits a number of similarities to the deity in the Raimondi Stele at Chavín de Huantar. Both stand frontally and carry a staff in each hand, grasping them in precisely the same manner. Their rayed headdresses/hairstyles extend outward in zoomorphic (animal-like) tendrils. The square, mask-like quality of their faces endows the deities with an ominous quality.

Archaeologists speculate that the doorway was originally brightly painted and inlaid with gold; thus, it is important to remember that the “pristine” and unadorned state of the ancient monuments we see today often bear little relationship to their original appearance.

Relationship with Chavín

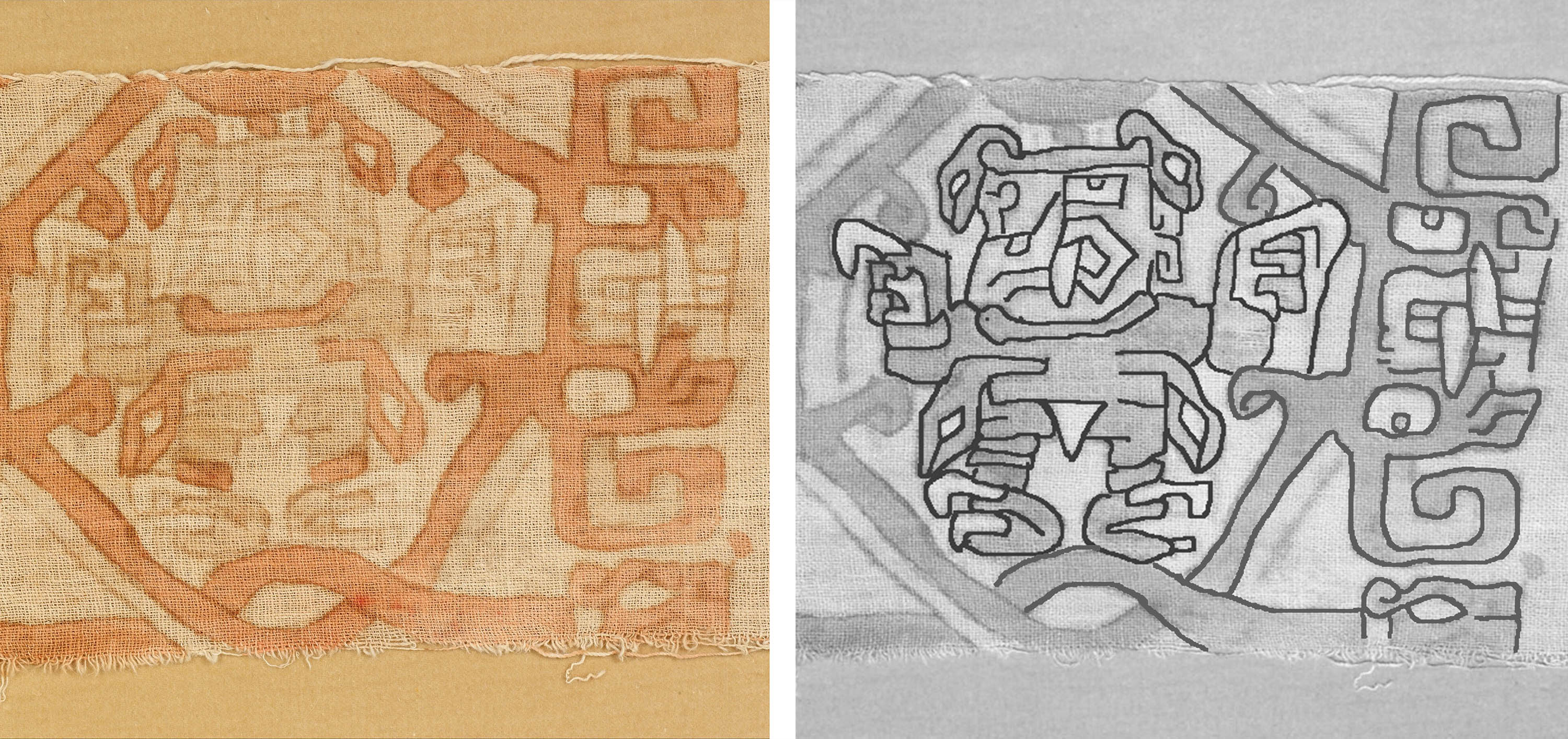

Textile fragment, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., Chavín culture, Peru, cotton, refined iron earth pigments, 14.6 x 31.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Adopting elements of Chavín iconography may have been a strategy for the Tiwanaku people to assert ancestral ties to the great early highland civilization. In the absence of a written language, images played a vital role in the transmission of ideas and values across space and time. Although the Chavín civilization had long succumbed by the time Tiwanaku reached its fluorescence, Chavín iconography traveled across the Andes through textiles and other portable objects, becoming continually reinterpreted and reinvented by each culture that came into contact with it.

Textiles and ceramics

Tiwanaku four-corner hat, 700–900 C.E., camelid fiber (Dallas Museum of Art)

While monumental stone structures and sculpture are the hallmarks of Tiwanaku art, smaller works in textile and ceramic of refined quality were also produced. Like the Wari, Tiwanaku men of high rank wore intricately designed four-cornered hats, brightly colored and decorated with geometric designs. In the example above, the overall diamond shape of the design has been divided into four sections, which is often a reference to the four cardinal directions. The rich red and blues come from difficult and expensive dyes, further emphasizing the wealth and power of the man who wore it.

Feline incense vessel, 6th–9th century C.E., ceramic (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tiwanaku ceramics, like the incense burner above, feature clean, somewhat blocky forms and surface decoration that echoes the aesthetic seen in stone sculpture, like the Gateway of the Sun above. A bold, black outline and flat areas of color characterize the painting. Here, an abstracted winged feline can be seen, with an eye divided down the middle between black and white, another typical element to Tiwanaku ceramic decoration. The painted feline head is rounder and more simplified than the sculpted one, which features more naturalistic, expressive eyes and an open mouth with prominent fangs.