In 1499, Alonso de Ojeda became the first Spaniard to step on what is today Colombian (as well as Venezuelan) soil. Often credited with circulating the myth of El Dorado, Ojeda’s expedition prompted that of later conquistadors, among them Jiménez de Quesada and Sebastián de Benalcázar. In 1525, the Caribbean coastal city of Santa Marta was established as the first Spanish settlement in Colombia, however it was the cities of Bogotá, Cartagena de Indias (commonly known as Cartagena), Tunja, and Popayán that would eventually rise to prominence.

Popayán, for instance, was a highly profitable city as a result of its reliance on mining and slavery, which ensured substantial wealth for the city, and thus permitted the commissioning of impressive religious monuments. Before Bogotá was proclaimed the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Granada (the name given to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in northern South America) in 1717, the city was home to the President of the Audiencia of Santa Fé, whose job was to oversee the Colombian provinces and report to the Viceroy in Lima.

An early colonial church in Bogotá

Church of San Francisco, Bogotá, 1556 (photo: Kamilokardona, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Bogotá, the oldest surviving colonial church (1556) bears a modest façade in comparison to what is found inside. Featuring one bell tower and a single nave interior, the Church of San Francisco features an elaborate retablo (altarpiece) that invades the entire area of the apse (the semi-circular at one end of the church).

Altarpiece, Church of San Francisco (photo: Felipe Restrepo Acosta, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The retablo is gilded, and adorned with biblical sculptures (such as St. John writing the Apocalypse), spiral fluted columns, and indigenous plants like coconut and chontaduro palm trees (chontaduro is the fruit of a palm tree that is native to the Pacific rim of Colombia). Not only does this demonstrate that the convergence of local and foreign iconography (symbolism) was a widespread practice in the colonies, but also that it was a trademark of early colonial churches, when the process of evangelization was in its early stages.

The Fortified City of Cartagena

Cartagena, founded in 1533, is located on the Caribbean coastline of Colombia. The city played an influential role in the dissemination of enslaved Africans throughout the viceroyalty. Due to its strategic position, Cartagena was not only an important trading post, but also a prime target for invaders, explaining the overwhelming presence of fortresses throughout the city. Starting in 1610, it also served as the seat of the Spanish Inquisition (founded in 1478 by Ferdinand and Isabel — King and Queen of Spain — to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms), which established only three Holy Offices in Latin America, one of which was Cartagena.

The city of Cartagena served as an important entry point into the Viceroyalty. Much like Veracruz, Cartagena was — and still is — an active port city. Enslaved people, gold, and silver were stored, exchanged, and shipped from Cartagena, which became wealthy and powerful during the colonial era. As a result, Cartagena, like other port cities in the Caribbean, such as La Habana and San Juan, was surrounded by thick and crenellated walls, hence its Spanish name as “la ciudad amurallada” (“the walled city”). This colonial city, contained within more than six miles of fortified walls, is unique in Latin America.

The Fortress of San Felipe (photo: KenWalker, CC-BY-SA-3.0)

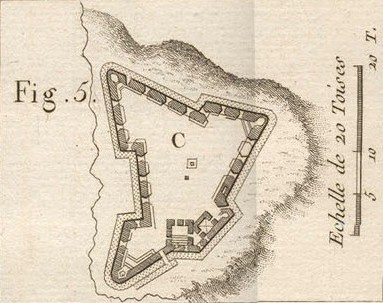

The Fortress of San Felipe, begun in 1630, was Cartagena’s main defense against French, Dutch, and English explorers, among them Sir Francis Drake, whose invasion of Cartagena in 1586 was known as the Caribbean Raid. These attacks continued into the eighteenth century, prompting various enlargements and renovations to the fortress. Located on a hilltop, the fortress provides a strategic view of both the city and port. Its thick walls (with foundations as thick as 65 feet), triangular design, and exterior ramp system make the fortress impenetrable, while a complex maze of underground tunnels connects this stronghold with the walled city.

Detail of the Fortress of San Felipe (photo: Nelsonc, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Early religious architecture in Tunja

Tunja, founded by Jiménez de Quesada in 1539, and Popayán, founded by Benalcázar in 1537, are also located in vastly different regions of Colombia. Through the efforts of important art patrons (such as Juan de Vargas, Gonzalo Suárez Rendón, and Juan de Castellanos), Tunja emerged as an intellectual and humanist center.

In Tunja, the Church of Santa Clara was the first convent of colonial Colombia. Its interior features, like at the Church of San Francisco in Bogotá, includes indigenous iconography. The golden sun, located prominently above the apse, held special significance for the Chibcha, who considered it their principal god, as well as life giving force.

Surrounding the golden sun, and throughout the interior of the church, bodiless angels appear to float aimlessly. With their heads located at center and surrounded by six wings, these seraphim recall the golden sun.

The fact that these solar symbols were made explicit both on the walls of the church, as well as on liturgical pieces, demonstrates the importance of hybrid iconography in the evangelization process, while their repetition might suggest insistency and forcefulness.

The House of the Scribe in Tunja

Iconography also played an important role in domestic architecture, particularly that of the renowned scribe Juan de Vargas. Commonly known as the House of the Scribe, it served as the home of the Vargas family, who arrived to New Granada in 1564. Under the patronage of Vargas, as well as that of the Spanish priest Juan de Castellanos and the founder of Tunja, Gonzalo Suárez Rendón, a humanist tradition began to brew in Tunja.

A ceiling in the House of the Scribe, Tunja, late 16th century (photo: Stefanrevollo, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Similar to what had occurred in Renaissance Europe, the teachings of the Church were combined with the ideas of classical philosophy, creating a culture that was as much intellectual as it was religious. This was reflected not only in the private libraries of Vargas and Castellanos, which contained books, prints, and manuals (many of them from Europe), but also in their art collection. At the home of Juan de Vargas for instance, an extensive mural program features a unique conflation of Roman mythology, Christian iconography, and European painting.

Detail of the Roman goddess Diana, murals in the House of the Scribe, Tunja, late 16th century (photo: Stefanrevollo, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The mural features an iconography unlike any other in New Granada, and less common across the American continent at the time. It includes depictions of the Roman Goddess of Wisdom, Minerva, and the Goddess of Hunt, Diana, combined with religious symbols such as the Latin cross.

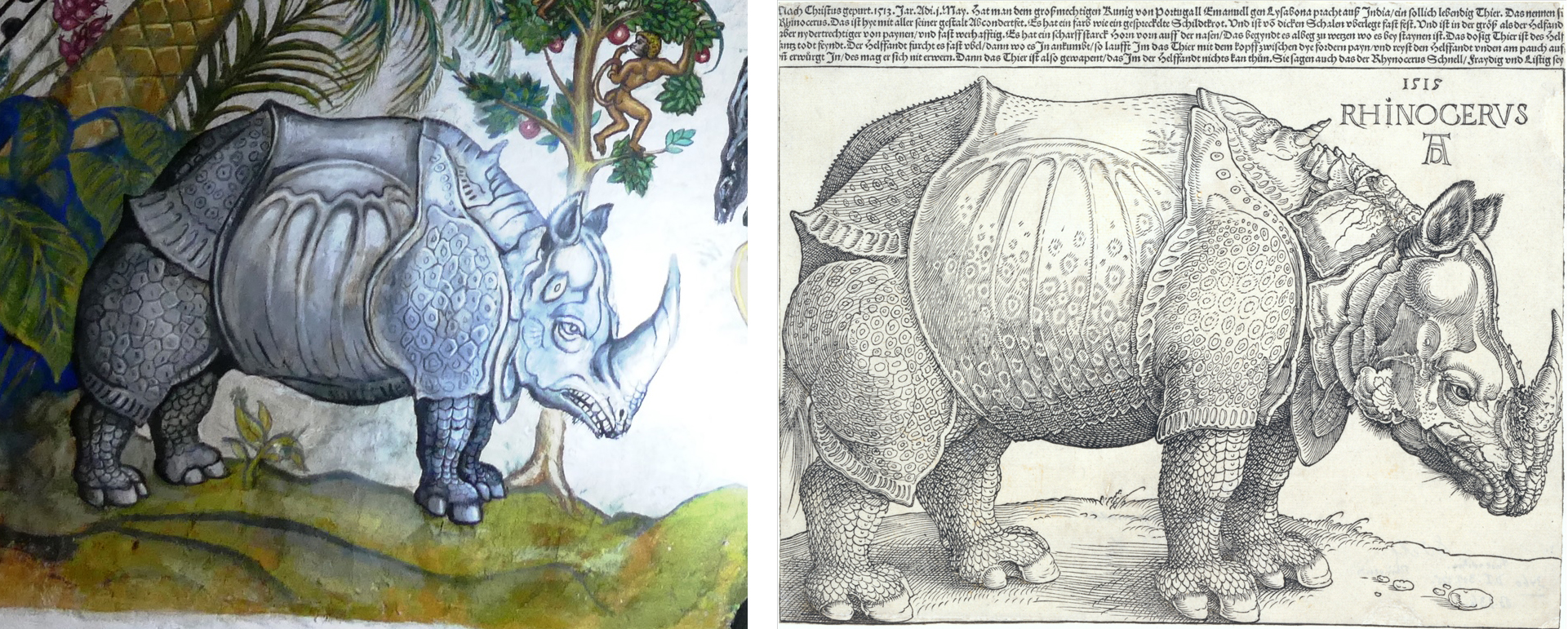

Even more interesting is the fact that these recognizable icons are set in a landscape of exotic flora and fauna, including a rhinoceros, which is not indigenous to Colombia. It is believed to have been copied from either an Albrecht Dürer print or from a copy of Dürer’s print by the Spanish engraver Juan de Arfe, published in De Varia Commensuración para la Escultura y Architectura (1587).

Left: detail of the rhinoceros, mural in the House of the Scribe, Tunja, late 16th century (photo: Stefanrevollo, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros, woodcut, 1515.

The end result is an eclectic combination of mythological and religious narratives set against a landscape of exotic figures, animals, and plants — revealing the cultural convergence that characterized the art of Spanish America.