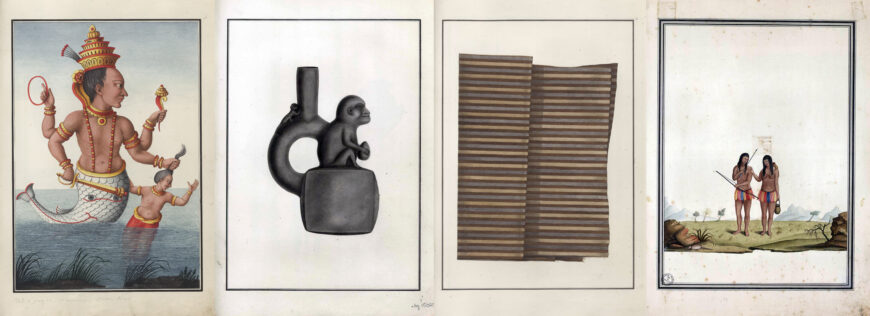

Four watercolors, left to right: “1st Incarnation Matsya Avatar;” “Monkey Vessel;” “Textile;” “Two Indigenous Brazilians” in Carlos Julião, Noticia Summaria do Gentilismo da Asia…, c. 1780–1800, watercolor (Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, C.I.2.8)

In the 1760s, Carlos Julião was dispatched by the Portuguese empire to go around the world. The National Library of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro holds an eclectic manuscript with seventy-six watercolors he produced on this voyage. The manuscript contains his report on India, ten drawings of Hindu deities, thirty-three images of Inka ceramics and textiles, and forty-three images of the “customs of the people of Rio de Janeiro,” Julião’s last stop and where his notebook remained. Our focus will be on four images from the Rio section that depict the tradition of festive Black kings and queens.

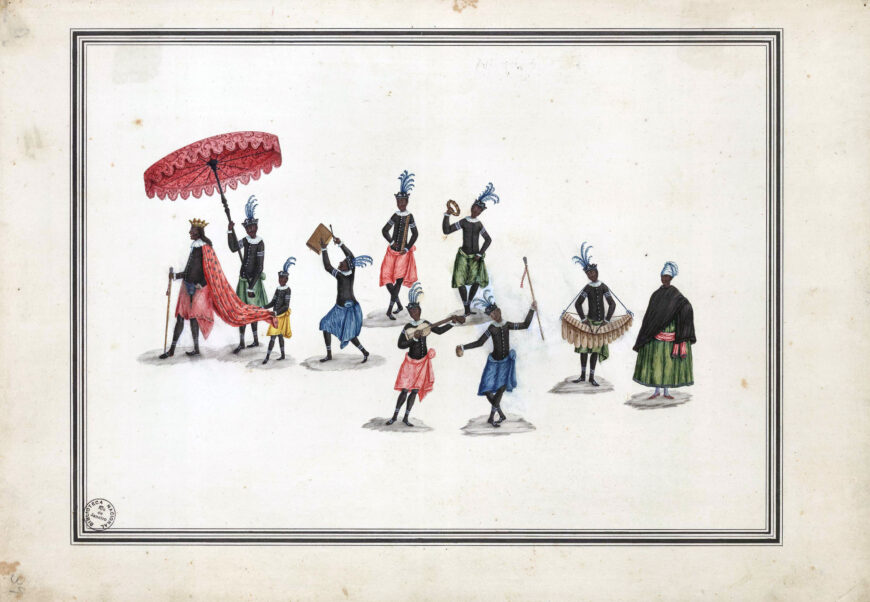

Carlos Julião, “Black King and Queen Festival,” last quarter of the 18th century (Brazil), watercolor on paper, in Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de brancos e negros dos uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro do Frio (Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, C.I.2.8)

Black kings and queens

In colonial Brazil, Black festive kings and queens would parade through the streets of its cities and towns accompanied by an entourage of attendants and musicians. This would normally take place on the first Sunday of October, the feast day of Our Lady of the Rosary. During his time in Rio, Julião witnessed this tradition and left one of the few surviving visual records from this time. By placing the performers on floating islands, however, Julião removed the figures from their colonial context. Had Julião drawn the context where these performances took place, we would see them performed on the patios of churches and the surrounding city of Rio through which they processed. One of these churches, run by a Black brotherhood, served as the cathedral of Rio de Janeiro for most of the 18th century. These performances, therefore, were staged in the heart of colonial power, and their audience would have included many of the city’s residents, including its large Black population.

From the 16th–18th centuries, the tradition of electing and crowning a ceremonial Black royal court was widespread throughout the Atlantic coast of the Americas, from New England to Buenos Aires. This tradition began in the Iberian Peninsula during the 15th century, as Afro-Iberians imitated or mocked European carnival performances, which included farcical royal courts. This mockery was mostly unproblematic for white Europeans because their own carnivalesque performances similarly mocked the ruling elite.

Eventually this Black performative tradition would become associated with Black Catholic brotherhoods. Afro-Brazilians added a Congolese martial dance known as sangamento, which was a mock battle that recalled the real war that led to the Christianization of the Kingdom of Kongo in the 1510s. The performance in Brazil thus combined an element that originated in Europe (Black kings and queens) with one that originated in Africa (sangamento).

Carlos Julião, “Black Queen Festival,” last quarter of the 18th century (Brazil), watercolor on paper, in Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de brancos e negros dos uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro do Frio (Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, C.I.2.8)

Black festive kings and queens were elected from among the brotherhoods’ leaders. Their function in the performance was ceremonial, but they were important members of the brotherhood and the local Black community. Women’s leadership is expressed through Julião’s depictions of three queens.

Queens were chosen from female brotherhood leaders or the leaders’ wives in the case of a male-led brotherhoods. Queens wielded real and symbolic power in these communities and institutions, and Black women enjoyed greater visibility within public spaces than Black men in colonial Latin America. [1]

Representations as historical evidence

While Julião’s watercolors should not be taken at face value, when compared with other sources, they help elucidate a widespread tradition among people of African descent in the Americas. Brotherhood records, contemporary eye-witness descriptions, inventories of Afro-Brazilian households, and later images suggest that Julião’s watercolors are plausible representations of these festivities.

Julião’s images constitute an important visual representation of early modern Afro-Brazilians’ brotherhoods and festive practices. His watercolors are among the few sources that depict the king’s and queen’s regalia, how the attendants dressed, and the music that accompanied these performances. Nonetheless, we must remain critical of them as documentary evidence. For while their great value lies in being among the few sources that give us a window into festive Black kings and queens and Afro-Brazilian musical practices, we may never know for sure to what extent they truthfully represent reality.

King, queen, and attendants (detail), Carlos Julião, “Black King and Queen Festival,” last quarter of the 18th century (Brazil), watercolor on paper, in Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de brancos e negros dos uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro do Frio (Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, C.I.2.8)

A writer and an artist as witnesses

In 1762, a Luso-Brazilian writer, Francisco Calmon, left us a description of this procession, focusing on the king.

The king was dressed most ornately with rich gold embroidery and golden cords with bright gemstones. About his waist was a beautiful alligator made of the same cords and in such a fashion that it seemed real. On his head, a gold crown, and on his right hand, a gold scepter. On his left, a hat adorned with feathers. His shoes were of gold embroidery with bright gemstones. The cape, which fell from his shoulders, was of red velvet with gold borders, and lined with white fabric with beautiful roses embroidered on it. The queen’s costume, which was in no way inferior, can be measured from the king’s. [2]

Carlos Julião, “Black King Festival,” last quarter of the 18th century (Brazil), watercolor on paper, in Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de brancos e negros dos uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro do Frio (Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, C.I.2.8)

Julião’s images complement Calmon’s description in remarkable ways. In both Julião’s watercolors and Calmon’s description, for example, we can see the great pageantry of the performance, especially the rich clothing In Juliaõ’s images, feathered caboclinhos appear as musicians, expanding our understanding of their roles in the performance. The watercolors portray both the use of European (e.g., trumpet, flute, and guitar) and African (e.g., marimba, box, and güiro) instruments, including some that are transcultural (i.e., used in both African and European music at the time), such as the tambourine, the drum, and the xylophone. Julião’s images are an important source for understanding 18th-century Afro-Brazilian musical practices.

Carlos Julião, “Black Queen Festival with Attendants in White,” last quarter of the 18th century (Brazil), watercolor on paper, in Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de brancos e negros dos uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro do Frio (Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, C.I.2.8)

Julião’s depiction of female musicians suggests that women were as central if not at the center of Black festive and music practices in colonial Brazil. We know that there were dances, for example, such as one known as talheres, that were associated exclusively with Black female dancers. Julião then may add to our understanding of this history by showing Black women playing musical instruments. Scholars have long believed that men were the main musical instrumentalists in Black music traditions. Julião’s watercolors encourage us to reconsider this assumption.

Julião’s two additional queens suggest that he saw several performances while in Rio de Janeiro. This would have not been too hard, as Afro-Brazilian neighborhoods had multiple brotherhoods that would process with their king and queen and their entourage on their feast day.

Julião’s images invite us to rethink the Black experience during the age of slavery, lasting from about 1500–1888. Five million Africans were enslaved into Brazil, making it the world’s largest slave society. The cruelties of Brazilian slavery had no limits. However, Afro-Brazilian brotherhoods and their festive practices remind us that Africans and people of African descent built lives beyond slavery by constructing moments of joy and sovereignty—a joy that they put into action through their brotherhood activities of sustaining kinship and mutual aid in sickness and in death.

Notes:

[1] Because authorities viewed Black men as potential criminals and rebels, their mobility was more limited than that of Black women in colonial Brazil.

[2] Francisco Calmon, Relação das augustissima festas (Account of the Most August Celebrations, 1762), folios 11–12.

Additional resources

Downloadable pdf of Carlos Julião’s manuscript

Jeroen Dewulf, From the Kingdom of Kongo to Congo Square: Kongo dances and the origins of the Mardi Gras Indians (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2017).

Peter Fryer, Rhythms of Resistance: African Musical Heritage in Brazil (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2000).

Cécile Fromont, “Dancing for the King of Congo from Early Modern Central Africa to Slavery-Era Brazil,” Colonial Latin American Review, volume 22, number 2 (2013), pp. 184–208.

Cécile Fromont, editor, Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance, Representation, and the Making of Black Atlantic Tradition (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019).

Silvia Hunold Lara, “Customs and Costumes: Carlos Julião and the Image of Black Slaves in Late Eighteenth-Century Brazil,” Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, volume 23, number 2 (2002), pp. 123–46.

Elizabeth W. Kiddy, Blacks of the Rosary: Memory and history in Minas Gerais, Brazil (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005).

Maria Manuela Tenreiro, “Military Encounters in the Eighteenth Century: Carlos Julião and Racial Representations in the Portuguese Empire,” Portuguese Studies, volume 23, number 1 (2007), pp. 7–35.

Miguel A. Valerio, Sovereign joy: Afro-Mexican kings and queens, 1539–1640 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022).