Map of South America showing the Andes (map: Mapswire, CC BY 4.0)

Mountain highlands to arid coastlines

The Andes region encompasses the expansive mountain chain that runs nearly 4,500 miles north to south, covering parts of modern-day Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. The pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Andes developed a stunning visual tradition that lasted over 10,000 years before the Spanish invasion of South America in 1532.

One of the most ecologically diverse places in the world, the Andes mountains give way to arid coastlines, fertile mountain valleys, frozen highland peaks that reach as high as 22,000 feet above sea level, and tropical rainforests. These disparate geographical and ecological regions were unified by complex trade networks grounded in reciprocity.

The Andes was home to thousands of cultural groups that spoke different languages and dialects, and who ranged from nomadic hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers. As such, the artistic traditions of the Andes are highly varied.

Pre-Columbian architects of the dry coastal regions built cities out of adobe, while highland peoples excelled in stone carving to produce architectural complexes that emulated the surrounding mountainous landscape.

Artists crafted objects of both aesthetic and utilitarian purposes from ceramic, stone, wood, bone, gourds, feathers, and cloth. Pre-Columbian Andean peoples developed a broad stylistic vocabulary that rivaled that of other ancient civilizations in both diversity and scope. From the breathtaking naturalism of Moche anthropomorphic ceramics to the geometric abstraction found in Inka textiles, Andean art was anything but static or homogeneous.

Characteristics

While Andean art is perhaps most notable for its diversity, it also possesses many unifying characteristics. Andean artists across the South American continent often endowed their works with a life force or sense of divinity. This translated into a process-oriented artistic practice that privileged an object’s inner substance over its appearance.

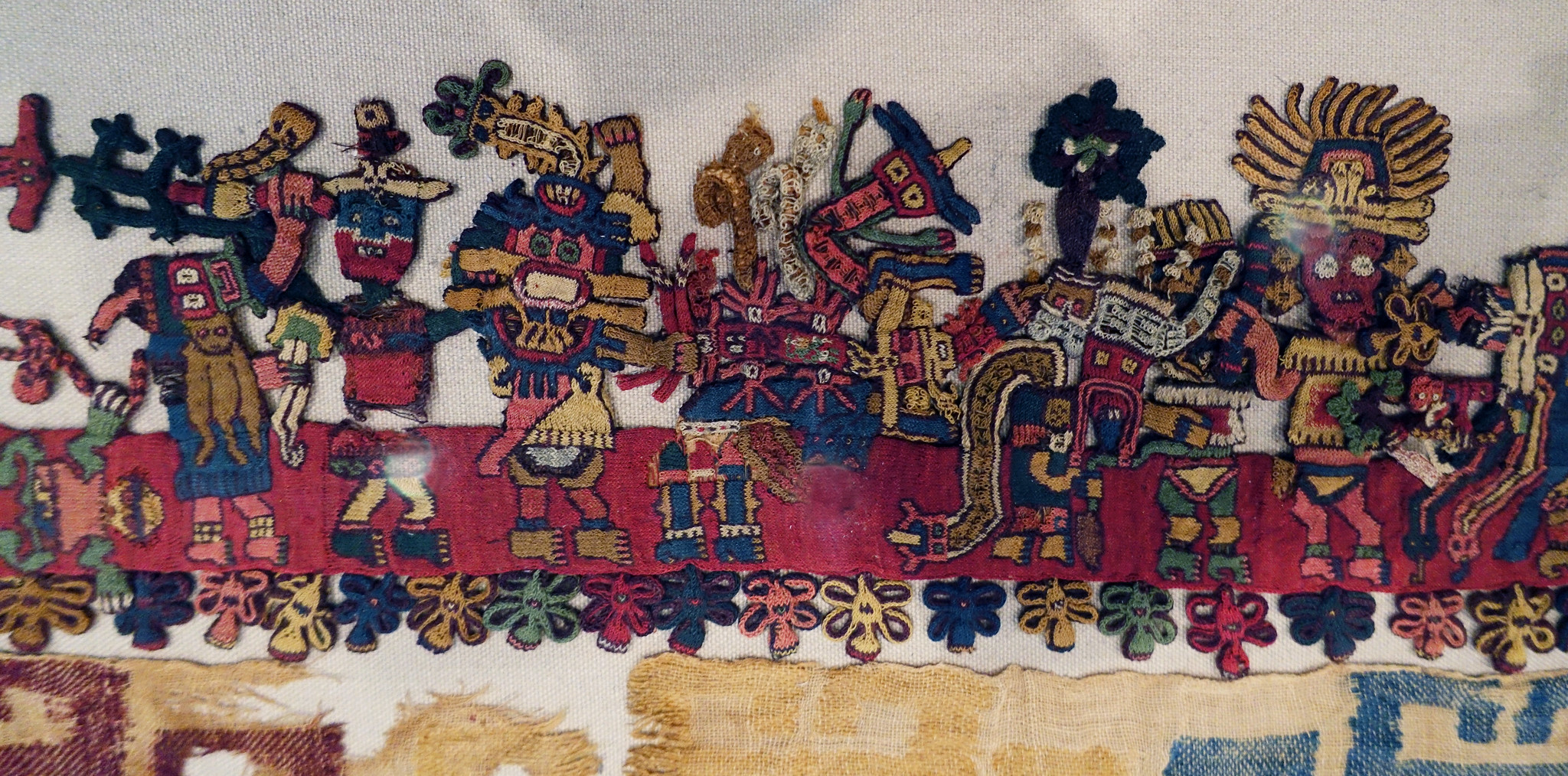

Border fragment, Paracas, 4th-3rd century B.C.E., cotton and camelid fiber, 1.43 x 12.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Andean art is also characterized by its environmental specificity; pre-Columbian art and architecture was intimately tied to the natural environment. Textiles produced by the Paracas culture, for instance, contained vivid depictions of local birds that could be found throughout the desert peninsula.

Hummigbird, Nasca geoglyph, over 300 feet in length, created approximately 2000 years ago (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The nearby Nazca culture is best known for its monumental earthworks in the shape of various aquatic and terrestrial animals that may have served as pilgrimage routes. The Inkas, on the other hand, produced windowed monuments whose vistas highlighted elements of the adjacent sacred landscape. Andean artists referenced, invoked, imitated, and highlighted the natural environment, using materials acquired both locally and through long-distance trade. Andean objects, images, and monuments also commanded human interaction.

A window frames a view of the surrounding mountains, Machu Picchu (photo: Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Worn, touched, held, maneuvered, or ritually burned

Pre-Columbian Andean art was meant to be touched, worn, held, maneuvered, or ritually burned. Elaborately decorated ceramic pots would have been used for storing food and drink for the living or as grave goods to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. Textiles painstakingly embroidered or woven with intricate designs would have been worn by the living, wrapped around mummies, or burned as sacrifices to the gods. Decorative objects made from copper, silver, or gold adorned the bodies of rulers and elites. In other words, Andean art often possessed both an aesthetic and a functional component — the concept of “art for art’s sake” had little applicability in the pre-Columbian Andes. This is not to imply that art was not appreciated for its beauty, but rather that the process of experiencing art went beyond merely viewing it.

Mantle, created to wrap a mummified body (“The Paracas Textile“), Nasca, 100-300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 148 x 62.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Detail, Mantle, created to wrap a mummified body (“The Paracas Textile”), Nasca, 100-300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 148 x 62.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

The supernatural

A bead from a necklace buried with the Old Lord of Sipán, 300-390 C.E., gold, 3 × 5.2 × 4.5 × 8.3 cm (photo: Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

At the same time that Andean art commanded human interaction, it also resonated with the supernatural realm. Some works were never seen or used by the living. Mortuary art, for instance, was essentially created only to be buried in the ground.

The magnificent ceramics and metalwork found at the grave of the Lord of Sipán on Peru’s north coast required a tremendous output of labor, yet were never intended for living beings. The notion of “hidden” art was a convention found throughout the pre-Columbian world. In Mesoamerica, for instance, burying objects in ritual caches to venerate the earth gods was practiced from the Olmec to the Aztec civilizations.

Works of art associated with particular rituals, on the other hand, were often burned or broken in order to “release” the object’s spiritual essence. Earthworks and architectural complexes best viewed from high above would have only been “seen” from the privileged vantage point of supernatural beings. Indeed, it is only with the advent of modern technology such as aerial photography and Google Earth that we are able to view earthworks such as the Nazca lines from a “supernatural” perspective.

Art was often conceived within a dualistic context, produced for both human and divine audiences. The pre-Columbian Andean artistic traditions covered here comprise only a sampling of South America’s rich visual heritage. Nevertheless, it will provide readers with a broad understanding of the major cultures, monuments, and artworks of the Andes as well as the principal themes and critical issues associated with them.

Additional resources:

Dualism in Andean Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Music in the Ancient Andes on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Birds of the Andes on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Elizabeth Hill Boone, ed., Andean Art at Dumbarton Oaks (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1996)

Sarahh Scher and Billie J. A. Follensbee, eds., Dressing the Part: Power, Dress, Gender, and Representation in the Pre-Columbian Americas (University Press of Florida, 2017)

Rebecca Stone. Art of the Andes: from Chavín to Inca (Thames & Hudson 2012)