Albert Eckhout, series of eight figures, 1641, oil on canvas (The National Museum of Denmark).

Map of Brazil in 1644, showing Dutch and Portuguese territories (source: Carl Pruneau, CC BY 3.0)

In 1630, the Dutch conquered the prosperous sugarcane-producing area in the northeast region of the Portuguese colony of Brazil. Although it only lasted for 24 years, the Dutch colony resulted in substantial art production. The governor Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen also encouraged scientific exploration and his palace in Mauritsstad (present-day Recife) included botanical gardens, a zoo, and a cabinet of curiosities. Maurits brought two artists, Albert Eckhout and the landscape painter Frans Post, to Brazil to document the local flora, fauna, people, and customs. One of Eckhout’s series of eight paintings helps us to understand how the Dutch artist encoded ethnic differences among the colony’s population.

Making order of a foreign world

Eckhout’s series consists of four life-size male-female pairs, each representing a different cultural or ethnic category. Although Eckhout collaborated with scientists on other projects, these monumental oil paintings employ the visual language of fine art rather than of scientific illustration. The compositions and poses are based on European portrait conventions and some panels include mythological references.

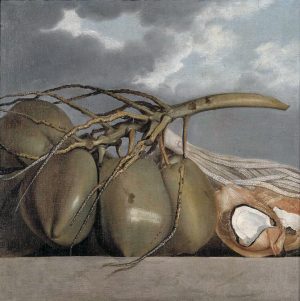

Eckhout may have used live models, and the level of detail gives the impression that these are portraits. However, they are meant to represent “types” rather than individuals. Much like New Spanish casta paintings, Eckhout conveys the moral and cultural stereotypes associated with each group. Clothing, jewelry, weapons, and baskets help to indicate the class and level of sophistication of the figures, while the proliferation of tropical fruits and vegetables advertises the natural abundance of the Brazilian land.

Hans Burgkmair, Left Side of King Cochin, from Set of Exotic Races, 1508, printed 1922 by the Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, woodcut, 26.6 × 35 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Today, scientists recognize that the idea of separate human races is socially constructed rather than based in genetics. Although the classification of peoples into groups has a long history in Western art and science, skin color was not a major defining factor until around the middle of the seventeenth century—around the same time that Eckhout painted this series. Before this, ethnic groups were conceptualized based on cultural characteristics. For instance, the early 16th-century woodcuts of Hans Burgkmair differentiated the peoples of Africa and India by their hairstyles, material culture, and behaviors, but united all the figures with the same type of idealized body. Eckhout, on the other hand, pays careful attention to skin color and physiognomy as he categorizes the people of Brazil.

Albert Eckhout, Coconuts, c. 1637-44, oil on canvas, 92 x 93 cm (The National Museum of Denmark)

Most scholars believe that these paintings were produced in Brazil to be hung in the governor’s palace. They may have been arranged around a large room with other paintings by Eckhout, including a portrait of Johan Maurits and still life paintings of tropical fruits and vegetables. The series functioned as an extension of Maurits’s cabinet of curiosities, enabling him to “possess” the portrayed figures. After the Dutch lost their Brazilian colony in 1654, Johan Maurits presented the paintings to the king of Denmark, as they had become unwelcome reminders of the failed colony.

Albert Eckhout, left: Tapuya woman, 1641, oil on canvas, 272 x 165 cm; right: Tapuya man, 1641, oil on canvas, 176 x 280 cm (The National Museum of Denmark)

Of cannibals and converts

The pair referred to as “Tapuya” represent native Brazilian tribes with whom Europeans were often engaged in battle. Their nudity, save for some leaves, strings, and small adornments, marks them as “uncivilized” in the eyes of the colonialists. The potential eroticism of the woman’s nudity is undermined by the references to cannibalism—in addition to the severed limbs that she carries, the dog at her feet probably alludes to the dog-headed cannibals that the ancient Greeks described as living in distant regions of the world.[1] The Tapuyas’ militarism is highlighted by the man’s weapons, as well as the distant group of armed figures behind the woman. The snake and spider at the man’s feet further emphasize the threat that the Tapuya represented to the Dutch.

Albert Eckhout, left: Brazilian woman, 1641, oil on canvas, 183 x 294 cm; right: Brazilian man, 1641, oil on canvas, 272 × 163 cm (The National Museum of Denmark)

In contrast to the Tapuya, the figures referred to as Brazilians are portrayed as having been tamed through their conversion to Christianity. Missionaries (Catholic under the Portuguese and Protestant under the Dutch) organized converted native Brazilians into aldeias (villages). The European-style building and tidy rows of trees in the orchard demonstrate European notions of the order that have been imposed on the Brazilian land. Both figures are partially clothed, and the woman’s bare breasts emphasize her nurturing role as mother. Unlike the Tapuya man’s club, the Brazilian man’s bow and arrows, not unlike their European equivalents, are meant for hunting animals rather than humans.

Albert Eckhout, left: African woman, 1641, oil on canvas, 282 x 189 cm; right: African man, 1641, oil on canvas, 273 x 167 cm (The National Museum of Denmark)

Africans on either side of the Atlantic

Eckhout’s African woman is shown as displaced from her homeland and forced into a world where Africans, Americans, and Europeans interacted. The American plants and native Brazilians fishing on the shore locate her in Brazil, but her hat and basket are African, while her jewelry and the pipe tucked into her waist are European. Although she probably represents a slave, the focus is not on labor but on her sexuality, as the child’s ear of corn points toward her genitals. The child’s lighter complexion may indicate that he is of mixed heritage: European men frequently had sexual relations, often coerced, with enslaved African women.

The African man literally stands apart from the other figures. He is not situated in Brazil, but in Africa, as indicated by the date palm (which is native to North Africa) and the ivory tusk on the ground, which exemplifies Africa’s trade goods. Although the sword, probably modeled after one in Johan Maurits’s collection, is more appropriate to a nobleman, the loincloth, ivory tusk, and palm tree probably stem from prints of traders in the Guinea coast, a major slave trading region. This painting is likely intended to portray a merchant involved in the slave trade that brought the woman to Brazil. Both of these representations of African people emphasize their musculature, reinforcing the European conception that Africans were inherently suited to manual labor and, thus, suited to being enslaved.

Albert Eckhout, left: mameluca woman, 1641, oil on canvas, 271 x 170 cm; right: mulatto man, 1641, oil on canvas, 274 x 170 cm (The National Museum of Denmark)

Between two worlds

The final pair of figures represents people of mixed race. The woman is a mameluca, of indigenous and white ancestry, and the man a mulatto, of black and white ancestry. The representation of the mameluca contains no references to agriculture or child-rearing. Instead, she solely provides voyeuristic pleasure to European males as she smiles cheekily at the viewer. The guinea pig reinforces her sexual availability because Europeans associated guinea pigs with rabbits, traditional symbols of fertility. To a European audience, the loose garment and flowers reference Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers and fertility who was adopted as a symbol for prostitutes and courtesans. In a place with few white women, the mameluca’s whiteness made her particularly desirable as a concubine.

In the eyes of Europeans, the so-called mulatto’s white ancestry likewise allowed him to rise above other Afro-Brazilians. He is posed in an authoritative military stance in front of a sugarcane field, the Dutch colony’s most important source of revenue. Likely tasked with protecting the fields and supervising the slaves, his appearance emphasizes his position within the social hierarchy between free and slave, European and non-European. His clothing is an imaginative mixture of European and foreign garments. While the offspring of enslaved women were born into slavery, children of white fathers were sometimes freed. Although bare feet can function as a visual symbol of enslavement, slaves were forbidden from carrying weapons—thus, the rifle and rapier suggest that he is free.

White supremacy and exploitation

Eckhout may have intended to show the relative levels of “civilization” of the various types of peoples depicted in these paintings, but scholars disagree on the order of such a hierarchy. It is clear that Eckhout viewed the represented ethnic groups to be inferior to white Europeans. The careful attention granted to skin color and physiognomy suggests that Eckhout and his patron believed Europeans possessed not only superior culture and morals, but also biology. The paintings help to convey the message that Europeans had both a right and a duty to control and acculturate foreign peoples.

The Dutch conquest of Brazil was economically motivated. These paintings accentuate the abundance and fertility of the Brazilian land, especially highlighting the lucrative sugarcane fields. The wealth generated by these endeavors, however, depended directly on the subjugation of both African and indigenous peoples. Eckhout’s portrayals of the inhabitants of Brazil and Africa as inferior to Europeans served to justify and advocate for both the enslavement of Africans and the exploitation of the Brazilian land and its inhabitants.

Notes:

1. Rebecca P. Brienen, Visions of Savage Paradise: Albert Eckhout, Court Painter in Colonial Dutch Brazil (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), 124.

Additional resources:

Albert Eckhout’s paintings at the National Museum of Denmark

Research materials on Dutch Brazil at the New Holland Foundation