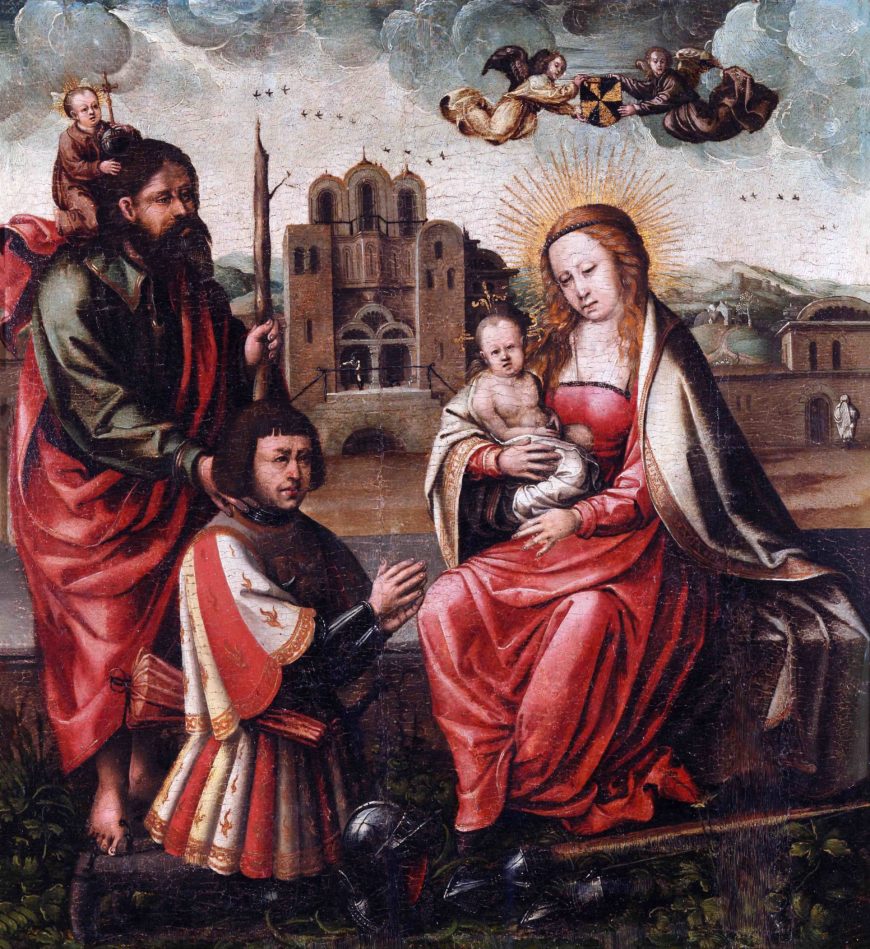

Virgin of Christopher Columbus, oil on panel, first half of the 16th century, 20 x 18 inches (Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid)

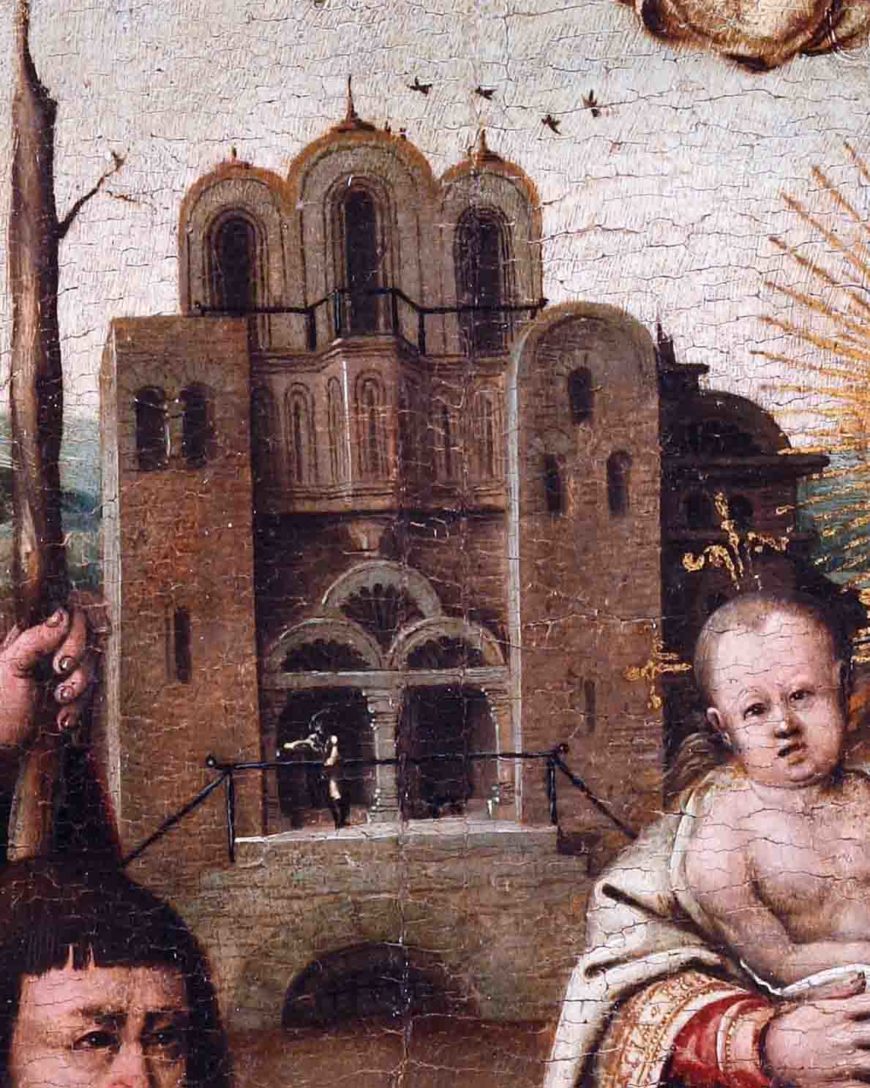

In the Lázaro Galdiano Museum in Madrid, a small painting shows Saint Christopher presenting Christopher Columbus to the Virgin Mary and Christ child. Columbus wears a gold-braided waistcoat inscribed with the Spanish heraldic motto of “Plus Ultra” (“Further beyond”—a Latin phrase and the national motto of Spain) over an armored suit.[1] The Basilica Cathedral Santa María la Menor of Santo Domingo—recognizable by its double-arched doorway—dominates the background.

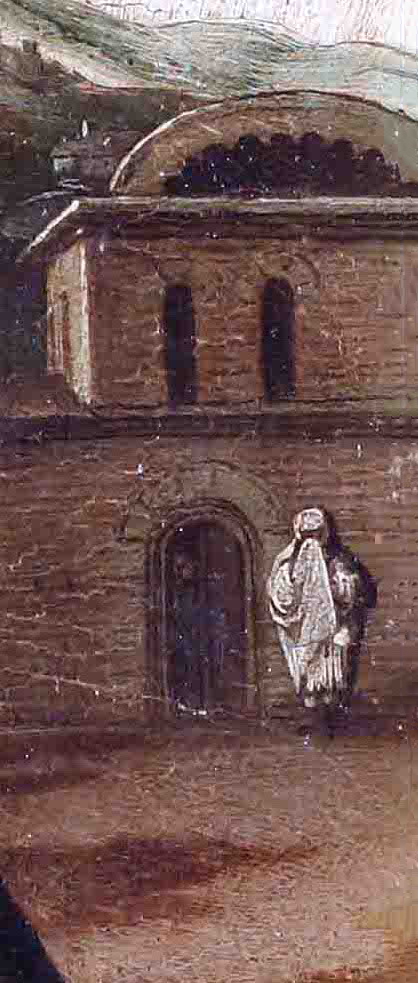

Detail of angels with the insignia of the Dominican Order (detail), Virgin of Christopher Columbus, oil on panel, first half of the 16th century, 20 x 18 inches (Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid)

Two angels float above the Virgin and carry the insignia of the Dominican Order, calling to mind the name of the city, Santo Domingo (Saint Dominic in English), the capital of the Caribbean island that Columbus named La española (eventually Hispaniola), named in honor of Spain, which had financed Columbus, and which Taíno peoples called Ayiti or Kiskeya. Today the island contains two nations, Dominican Republic and Haiti.

Detail of figure in the background, Virgin of Christopher Columbus, oil on panel, first half of the 16th century, 20 x 18 inches (Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid)

The association of Santo Domingo with the Dominican order relates to the foundation of the city on the eastern banks of the Ozama river (by Columbus’s brother, Bartolomé) on the feast day of Saint Dominic of Guzmán, who founded the Dominican Order in 1216. The day coincidentally happened to be Sunday (in Spanish, Domingo), and the name of Columbus’s father was Domenico (Domingo, in Italian)— sealing the choice of the name for the city.

One figure in the background of the painting might strike the viewer as out-of-place because he is dressed in a turban and tunic. Yet this “Moorish” dress was not uncommon in Spain, especially because Muslims had controlled most of the Iberian peninsula (today Spain and Portugal) for hundreds of years. What is less well known is that enslaved Black Moors (Muslim inhabitants of Iberia) had been in Hispaniola since at least 1550 despite a royal prohibition. A letter (dated 1550) from Santo Domingo officers to the crown asks the king to exempt the (at least) 100 enslaved Moors of Hispaniola from the 1543 royal prohibition because they performed various trades.[2] Under the watchful gaze of this turbaned figure, Columbus surrenders his helmet, gauntlets, and spear at the feet of the Virgin, offering her the first Christian city of the Americas.

This painting reveals the early European interest in picturing the so-called “New World” (many people were unable to travel to the Americas, but wanted to see what it looked like). The turbaned figure also stands as a reminder to peninsular viewers (or people living on the Iberian Peninsula) of threats to Christian dominance. The final Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula only fell to the Spanish Catholic Monarchs in 1492, followed by the expulsion of Muslims and Jews who refused conversion to Christianity. In the painting, the turbaned figure provides a justification for the colonization of the Americas.

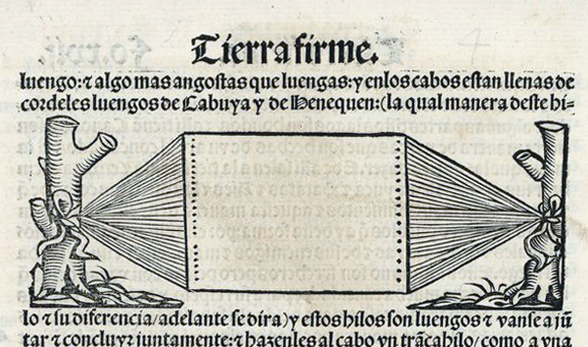

A hammock in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Natural and General History of the Indies (Toledo: Ramon Petras, 1526), p. 34

It is possible the painter worked in Seville as part of the large picture-making industry dedicated to producing religious images (especially of the Virgin Mary) to aid in conversion in the Americas. The artist would not have seen Santo Domingo firsthand, but learned about it from images or written accounts. A letter Columbus sent announcing the news of the “discovery” included, in its different editions throughout Europe, several engravings depicting America and its inhabitants. Royal chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s Natural and General History of the Indies also introduced Europeans to the fauna, flora, and peoples of Hispaniola, which he had observed in person. His book included the first illustrations of the pineapple, the hammock, the barbecue, and tobacco.

A Blueprint for Colonization

The European invasion and colonization of the Americas was launched in 1492 from Hispaniola. For sixteen years, Hispaniola was Spain’s only active colony in the hemisphere, making the lessons learned on the island an important part of the playbook for colonizing elsewhere in the Americas. In 1493, Columbus and his crew arrived after the second voyage ready to establish a trading post in the style of Portuguese feitorias (factories), which were fortified, coastal trading houses that the Portuguese set up in west Africa to monopolize trade in gold and enslaved peoples. They served as warehouses and customs agencies mediating exchange between local trading networks and European monarchs. The second voyage also brought Franciscan missionaries who would begin the process of conversion; by 1500 they had baptized 3,000 Indigenous people.

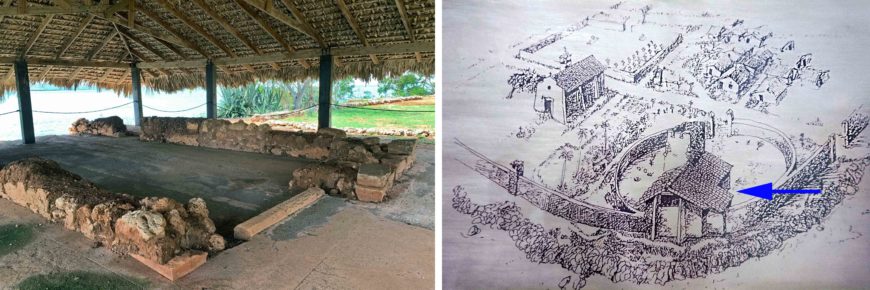

House of Columbus, La Isabela, Dominican Republic, 1494–98 (photo: Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: reconstruction drawing of La Isabela, with the House of Columbus indicated with an arrow (photo: Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz, CC BY-SA 4.0)

La Isabela, the first European settlement of the Americas, was founded on January 6, 1494 in today’s Puerto Plata province (in northern Hispaniola), after the celebration of a mass during which Amerindians first saw a sculpture of the Virgin Mary in the context of Catholic liturgy. The experiment at La Isabela failed after four years because the all-male settlement suffered starvation, absences by Columbus who left to explore Cuba, indigenous resistance, and a mutiny led by Columbus’s former servant, Francisco Roldán.

A map of Santo Domingo show the city’s grid plan. The cathedral is the large building in the center of the grid. Giovanni Battista Boazio, View of Santo Domingo, 1589, hand-colored engraving, from Map and views illustrating Sir Francis Drake’s West Indian voyage, 1585–6, published in Leiden (Jay I. Kislak Collection Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress)

Detail of Cathedral of Santo Domingo, Virgin of Christopher Columbus, oil on panel, first half of the 16th century, 20 x 18 inches (Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid)

Before La Isabela failed, the Spanish monarchy had ordered the change of the site’s status from trade post to a fully imperial venture in a move to centralize power.[3] This change tells us that the Spanish monarchs wished to expand their empire. With a defined, imperial venture in mind, governor of the Indies Nicolás de Ovando arrived on the island with 2,500 colonists, and founded Santo Domingo proper in 1502 after moving it to the western banks of the Ozama river. He developed the city using a rectilinear grid known as a traza, which anchored church, elite residences, and government buildings around a main plaza, with streets meeting at right angles. This organization had several advantages including peripheral and internal surveillance, and possibilities for expansion. With its ideal proportions, the traza symbolized the idealized civility and order of classical Rome. The work of ancient Roman architect Vitruvius enjoyed a resurgence in fifteenth-century Europe, and Spaniards reproduced this classical architectural language in their own imperial pursuits. Before the Americas, they implemented the grid model to subjugate the Canary Islands, as well as in the military encampment of Santa Fe de Granada on the eve of the final battle to recapture Spain from Muslim control. Another source for urban planning in the early Spanish Americas was the prophet Ezekiel’s vision of Heavenly Jerusalem which offered the Spanish crown the opportunity to promote Santo Domingo as the heavenly city, thus raising its political and religious stature.

Cathedral of Santa María la Menor, Santo Domingo, 1519–1541 (photo: Martin Falbisoner, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Cathedral Basilica of Santo Domingo was important to the city’s early urban development—it was the center of city life. Construction of the Cathedral began in 1514 (possibly 1523) and finished in the 1540s, well after the city’s residents had begun to emigrate to newly conquered territories. The coral limestone façade featured a pediment and portico—elements borrowed from classical architecture), and prominently displayed the shield of Habsburg Emperor Charles V. Ornamented tabernacles, flanking the double-arched entranceway, houses statues of the apostles, evoking the Spanish empire’s evangelizing mission. This classicizing language fits with other urban elements in the city, such as the traza (the grid structure).

Virgen de la Antigua in Santo Domingo Cathedral

Early colonial artworks found inside the Cathedral speak to the transatlantic crossings of popular Iberian religious images and devotions. In his book, Oviedo, the Royal chronicler, writes,

“a large image of our Lady of Antigua, today in the main church of this city in the altar next to the sacristy, copied from the image of Antigua in the main church of Seville.”[4]

According to Oviedo, the painting was placed in the Cathedral of Santo Domingo in 1523 after captain Francisco Vara (from Seville) found it floating in the Caribbean ocean, the only object retrieved from his vessel’s shipwreck.

Left: Painting from the left side of the main entrance: Virgen Nuestra Señora de la Antigua with two unknown donors, oil on panel, 275 cm x 174 cm, 1520–1523, Cathedral Basilica Santa Maria la Menor, Santo Domingo (photo: Li Tsin Soon, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); right: similar painting with Ferdinand and Isabel, Virgen de la Antigua with Isabel and Ferdinand, date unknown, presbytery of Cathedral Basilica Santa Maria la Menor, Santo Domingo (photo: Tyler Black, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This painting is likely one that hangs in the Santo Domingo Cathedral today, displayed on the left side of the main entrance. It features a standing Virgin, carrying the Christ child with her left arm and a flower in her right hand. Two angels hover above her head holding her crown, and two unidentified donors appear below.[5] Diagonally across from this painting, on the right side of the presbytery, another Virgen de la Antigua painting with similar iconography can be seen, except that the donors pictured in the lower segment are the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel.[6]

The Virgen de la Antigua was a popular form of the Virgin Mary in Spain, and stories circulated of her miraculous intervention on behalf of Christian kingdoms during the Reconquest. In one of the decisive battles in the 13th century, the image of the Virgen de la Antigua allegedly appeared in a vision to Fernando III of Castile as a mural painting inside a mosque in Seville, signaling an imminent victory against Muslim forces. Her image eventually traveled to the Americas as part of Europe’s colonial expansion in the 16th century. Devotion to her inspired votive offerings thanking or petitioning the Virgin for a safe passage, such as we see in the two paintings in the Cathedral today. Devotees also visited the image in the cathedral to implore her protection against storms and catastrophes as people coped with the unpredictability of nature.

In this early period, a great deal of art was produced in Spain for shipment to Hispaniola. Much of it was religious, made for Christian liturgical and devotional purposes. Still, there would have also been secular portraiture, sumptuous textiles, and other movable objects (like furniture) that marked the owner’s social standing. While commercial painters in Seville produced many of the works that arrived during the early colonial period, some were made by more prominent artists and their workshops, such as Alejo Fernández and Juan Martínez Montañes. Much of this early art no longer survives unfortunately. Owners emigrated with their art, storms destroyed work, and the Francis Drake’s sacking of Santo Domingo in 1586 led to the disappearance of some early colonial art as well.

Reception of Images

Art that arrived in Hispaniola aboard the first Spanish fleets forced a reckoning between cultures that did not understand or use images in the same way. In one infamous encounter, Taínos seized an image of the Virgin from an oratory, buried it in a field, and urinated on it. Seeing the incident as an insult, Columbus’s brother ordered the natives burned alive. Catalonian Hieronymite friar Ramón Pané recounts this story in the opening of his ethnographic report, An Account of the Antiquities of the Indies (completed in 1498), to suggest Taíno idolatry.[7] For the Taíno however, the venerated image could fertilize the ground just like a zemi (sculptures of wood, stone, or clay, that sheltered deities or ancestral beings). Art historian Amara Solari suggests that Taíno believed that the Marian icon embodied precontact numinous (supernatural or holy) qualities, allowing them to transpose the zemi and Christian icon.

Radiocarbon testing dates the Pigorini zemi after Contact, between 1492–1524 C.E., rhinoceros horn, cotton, shell, glass beads, mirrors, gold, vegetable fiber, pigment, resin, wooden mount (Museo Nazionale Prehistorico ed Etnografico “Luigi Pigorini,” Rome, Italy; photo: Lorenzo Demasi)

False starts like these, the persecution of so-called idolatry, and the near genocide of the Taíno within the first fifty years of European arrival (due to diseases and cruel labor practices), doomed the potential development of transcultural aesthetics (the merging of cultural elements into a completely new iteration) during the early colonial period. Still, one surviving zemi (called the Pigorini zemi) hints at the ways different cultures and visual systems converged during the early colonial era. Its mix of African rhinoceros horn and European glass beads demonstrate the different cultures, artistic practices, and materials that convened in Hispaniola.

![Diego Valadés, “Friar Preaching to Native Converts,” 1579, copperplate engraving, within Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi et orandi usum accommodate […] ex Indorum maximè deprompta sunt historiis. Perugia: Petrus Jacobus Petrutius, 1579.](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Houghton_Typ_525.79.865_-_Rhetorica_christiana_Diego_Valadés_211-870x1195.jpg)

Diego de Valadés, “Friar Preaching to Native Converts,” 1579, copperplate engraving, within Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi et orandi usum accommodate […] ex Indorum maximè deprompta sunt historiis. Perugia: Petrus Jacobus Petrutius, 1579.

Fragment of Christ figure, 16th century, carved lignum vitae, found in San Rafael Cave, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress; photo ©Justin Kerr, Kerr Associates)

Archaeological material can help us learn about the use of images and spaces for instruction and religious conversion in Hispaniola. A fragment of a small wooden sculpture of Christ found in San Rafael Cave in Santo Domingo is a type of religious prop employed in this exchange. Chapels or private oratories (small chapels for private worship) in the estates of encomenderos could have also functioned as early conversion sites after the Laws of Burgos of 1512 ordered that Spaniards build churches within their haciendas and display images to instruct the Taíno.

Hispaniola was the first point of long-term contact between the cultures of Europe, America, and Africa. The visual and material culture, such as paintings of Marian miracles, helped people stake territorial and identity claims. More research is needed to bring to light the production and reception of art by Amerindians, Africans, and mixed-race peoples, as well as to fully illuminate the implications of early Hispaniola’s role in subsequent colonial schemes.

Notes:

[1] Emilio Rodríguez Demorizi, España y los comienzos del arte y la escultura en América (Santo Domingo: Gráficas Reunidas, 1966), pp. 95-96.

[2] See José Antonio Saco. Historia de la esclavitud de la raza africana en el nuevo mundo y en especial en los países américo-hispanos. Habana: Cultural, 1938. Vol. I, pp. 305–306.

[3] Pauline Kulstad-González, Hispaniola: Home of Hell? Decolonizing Grand Narratives about Intercultural Interactions at Concepción de la Vega (1494–1564) (Sidestonepress, 2020).

[4] Oviedo, Historia de las Indias, Madrid, 1855, Vol I, 426.

[5] The painting is dated to c. 1520–1523 by Dominican art historian, Danilo de los Santos, in Memoria de la pintura Dominicana: Raíces e impulso nacional, Vol. 1 2000 AC 1924 (Santo Domingo: Grupo E. León Jiménez, 2003), 100. Santos, quoting the Marques de Lozoya (in Demorizi, España y los comienzos del arte, 1966, p. 9) writes that this is the oldest version of La Antigua in the country. Santos associates this painting with Oviedo’s story about a painting of La Antigua surviving a shipwreck. Demorizi, however, dates the painting to 1500, p. 50.

[6] Demorizi dates this painting to 1520. See Demorizi, España y los comienzos del arte, 101. Additionally, according to a publication by the Fundación de la Zona Colonial, this is the panel that Oviedo says was rescued from a shipwreck, and it was brought to Santo Domingo in 1527. See Arte Sacro Colonial en Santo Domingo (Santo Domingo: Amigo del Hogar, 2002), pp. 38 and 16 [No sources offered].

[7] Ramón Pané, Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios, 53–54. As seen in Gruzinski, Images at War, footnote 24.

Additional resources

Learn more about the legacy of the Reconquest in Latin America and Columbus’ Landing and Erasing Native Resistance from Unsettling Journeys

Alemar, L. La Catedral de Santo Domingo: Descripción Histórico-Artístico Arqueológica de Este Portentoso Templo, Primada de Las Indias. Barcelona, Spain: Casa Editorial Araluce, 1933.

Brown, J. “Spain in the Age of Exploration: Crossroads of Artistic Cultures.” In Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration, ed. J. Levenson, 41–43. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991.

Conley, Tom. “De Bry’s Las Casas.” In Amerindian Images and the Legacy of Columbus. R. Jara, N. Spadaccini, eds. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

Deagan, Kathleen A., and Jose Maria Cruxent, Archaeology at La Isabela: America’s First European Town. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, accessed July 5 2020.

De los Santos, Danilo. Memoria de la pintura dominicana. Santo Domingo: Grupo E. León Jimenez, 2005.

Fernández de Oviedo y Valdes, Gonzalo. Historia general y natural de las Indias. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1851.

Gaudio, Michael. Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008)

Guitar, L. 2006. “Boiling it Down: Slavery on the First Commercial Sugarcane Ingenios in the Americas (Hispaniola, 1530–45).” In Slaves, Subjects, and Subversives: Blacks in Colonial Latin America, eds. J. Landers and B. Robinson, 39–82. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Gruzinski, Serge, Images at War: Mexico from Columbus to Blade Runner (1492-2019), transl. Heather McLean. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

Kagan, Richard. Urban Images of the Hispanic World 1493-1793. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Kulstad-González, Pauline M, Hispaniola: Home or Hell? Decolonizing Grand Narratives about Intercultural Interactions at Concepción de la Vega (1494-1564) Sidestone Press Dissertations, 2020.

Matthew, Restall, and Lane, Kris. Latin America in Colonial Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Niell, Paul. Caribbean Art and Architecture under Spanish Colonial Rule (1492-1898). Oxford Art Online, 2018. Accessed as of August 8, 2020, https://doi-org.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/10.1093/oao/9781884446054.013.2000000077

Niell, Paul, “The Late Gothic,” Postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies (2015) 6, 243–257. doi:10.1057/pmed.2015.23

Ostapkowicz, Joanna, Fiona Brock, Alex C. Wiedenhoeft, Rick Schulting & Donatella Saviola, “Integrating the Old World into the New: an “Idol from the West Indies”. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 90.202.6.114, on 21 Sep 2017 at 15:42:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.151

Otte, Enrique, “La flota de Diego Colón. Españoles y genoveses en el comercio trasatlántico de 1509”, Revista de Indias, Madrid, 1964, No. 97-98, 475.

Palm, E. 1945–1946. Plateresque and Renaissance Monuments on the Island of Hispaniola. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 5: 1–14.

Palm, E. 1944. Rodrigo de Liendo: Arquitecto en La Española. Ciudad Trujillo, Dominican Republic: Editorial ‘La Nación,’ de Luis Sánchez Andújar.

Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio. España y los comienzos de la pintura y escultura en América. Santo Domingo: Gráficas Reunidas, 1966.

van Groesen, Michiel, “The de Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634): Early America reconsidered,” Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008): 1–24.

Waldron, Lawrence. Pre-Columbian Art of the Caribbean. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2019.