Fountain of San Miguel in the main plaza of Puebla, with the Cathedral towering in the background (photo: Gusvel, CC BY 3.0)

Standing at Puebla de los Ángeles’s central plaza, one can see people walking under tall, leafy trees and passing by the beautiful baroque water fountain in the square’s center. The square and its delimiting streets are of an exacting geometry: the square is a perfectly traced rectangle lined by arcades on three of its sides.

The rounded Roman half arches that make up those arcades are built of grey basaltic stone typical of many of the city’s historical constructions and supported by classical columns made of the same material. Above the arcades are rows of buildings of equal height, while on the fourth side of the plaza, toward the south, stands the imposing city cathedral, which towers above the square, severe looking in its basaltic grey stone finish and carefully crafted classical ornamentation.

The city was built on a grid plan—a series of intersecting orthogonal streets with a square at the middle where the most important civil and religious buildings coexisted, with orderly rows of buildings of similar heights lining the streets. This grid plan was the result of a long tradition of ideas about how cities should be designed.

Located in central Mexico, Puebla is today a large, thriving city. It is well-known for its colonial urban design, which was influenced by ideas about renaissance classicism, including concepts of order, perspective, and decorum (propriety or appropriateness). These concepts (discussed more below) arrived in the Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain (as Mexico was known during its colonial period) together with the Spanish colonizers, who employed these notions to establish many cities in the Spanish Americas. Renaissance classicism not only influenced the way cities were designed, but also shaped and influenced other forms of cultural expression, such as architecture, books, and painting.

Renaissance humanism and classicism

What do we mean by renaissance classicism? Classicism here refers to that which is tied to ancient Greek and Roman cultures, while the related term renaissance humanism (known as studia humanitatis during the early modern period) was an intellectual movement that changed and renovated European thinking through the study of classical texts by the ancient Greeks and Romans, starting sometime in the late 14th century. To a large extent, the Italian renaissance—understood as a broad cultural movement—was fueled by humanism, given that the renaissance sought to study those classical texts and apply them to aesthetic and practical ends, such as the pictorial arts, literature, urbanism, and architecture, among others. It is broadly accepted that renaissance classicism began in northern Italy, spreading to other parts of Europe soon after, including Spain, and from there to the American continent via European colonizers.

The classical architectural tradition in Puebla de los Ángeles

Puebla was founded originally by Spaniards as a city exclusively for European colonizers. From its humble origins in 1531, Puebla grew quickly. It is estimated that the city had some 800 households by 1570. By 1600 that number had risen to about 1,500 households distributed in some 120 urban blocks.

The city’s central core, known as the traza principal or “main layout,” was the city’s most densely populated area. The plaza principal or main plaza marked the center of the city and contained a public water fountain and a pillory. Around the square stood important buildings made out of durable, stone masonry like the city hall and eventually an ambitious new cathedral building. Close to the main plaza stood the residences of the city’s elite (who were overwhelmingly Spaniards or criollos, their offspring). Meanwhile, in the city’s peripheries, communities of Indigenous migrants who came from neighboring native cities like Cholula or Huejotzingo (or some from the towns close to Mexico City, like Texcoco) lived in more informal constructions made out of adobe or shacks called jacales. Cramped tenements were also scattered throughout the city for the poorest inhabitants.

Puebla de los Ángeles quickly became New Spain’s second most important urban center and populous city after the viceroyalty’s capital, Mexico City. It was also an important artistic market for the whole viceroyalty and a popular destination for builders, thanks to wealthy elite Spanish colonizers. After settling in the Americas, they not only wished to emulate and replicate (as much as possible) the lifestyles and built environments of Spain, but also considered their way of life superior to that of the Native population, which was a reason they felt it their obligation to convert the Native population to their ideas about the benefit of living in cities. Most Indigenous towns in Mesoamerica, prior to the arrival of Europeans, were less dense than European cities. People lived scattered in the country, their homes surrounded by parcels of land. Residential units surrounded a core urban center where the community’s temples, markets, and the local elite lived. Mesoamerican cities also possessed deep connections to their natural environment, such as rivers, mountains, valleys, and more, which in turn connected their towns and villages to their cosmological belief system. Considering these traits, the Mesoamerican and European traditions differed greatly. In this way, renaissance classicism was part of a larger colonial enterprise that included the imposition of language, religion, and even the shaping of the built environment in the Spanish Americas.

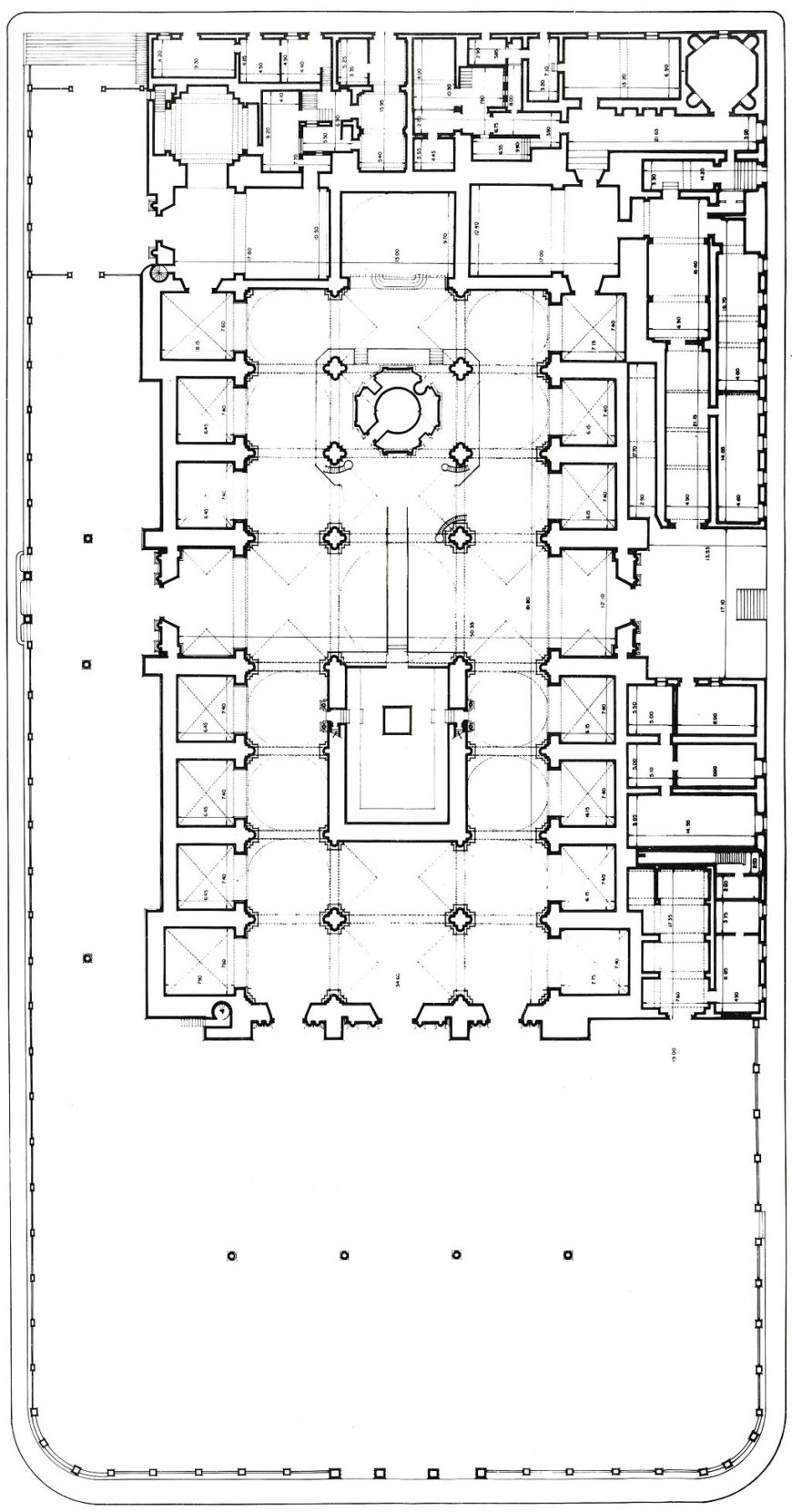

El Escorial was the pet architectural project of Philip II, who personally supervised many elements of its construction, and which would be completed by the 1580s. El Escorial, begun 1563, near Madrid, Spain

In Spain, classicism would become the primary architectural style (over gothic, mudéjar, and plateresque ornamentation) because the Spanish monarchs Charles V and later his son, Philip II, used the classical style in some key buildings that they sponsored to emulate an idea of imperialism, perhaps reminiscent of the ancient Romans.

The case of El Escorial located close to Madrid in Spain is particularly outstanding. King Philip II set out to build a palace that would also be the burial vaults of his family lineage, the Habsburgs. The building contains an impressive and enormous library and also a monastery. The building uses a strict and sober classical vocabulary, evident in the simple and stark composition that uses the classical orders in a simple and straightforward manner, always employing heavy-looking columns, entablatures, and repetitive, symmetrical patterns in the distribution of voids and massing. The influence of the northern territories of Flanders, then a part of the Habsburg’s empire, is seen in the characteristic sloped, dark slate-tiled roofs, and the pointed turrets at the building’s corners.

Knowledge of renaissance architectural classicism (or the “Roman style”) arrived in New Spain with educated Spaniards, like the first viceroy of the viceroyalty, Antonio de Mendoza, who brought many books from Spain with him and was well-read in many subjects, including architecture. Mendoza owned a copy of Italian renaissance humanist Leon Battista Alberti’s famous treatise on architecture called De re aedificatoria, written originally around 1450 in Italy and based on the treatise by the ancient Roman architect and engineer Vitrivius. De re aedificatoria was thoroughly dedicated to architecture, and discussions such as what made an architect, what were architecture’s classical rules on composition, how might an architect better design a building, among other topics.

Mendoza and his successor, Luis de Velasco, were also concerned with attracting European architects to New Spain to take on important building endeavors, such as cathedrals, city halls, hospitals, and other infrastructure works. The first Spanish architect trained in the classical tradition to arrive in New Spain was Claudio de Arciniega, who settled initially in Puebla. While there, Arciniega ornamented a public water fountain at the city’s main plaza, worked on the ornamentation of the city’s alhóndiga (city public granary), and began working on Puebla’s new cathedral, until he was lured, after a couple of years, to Mexico City.

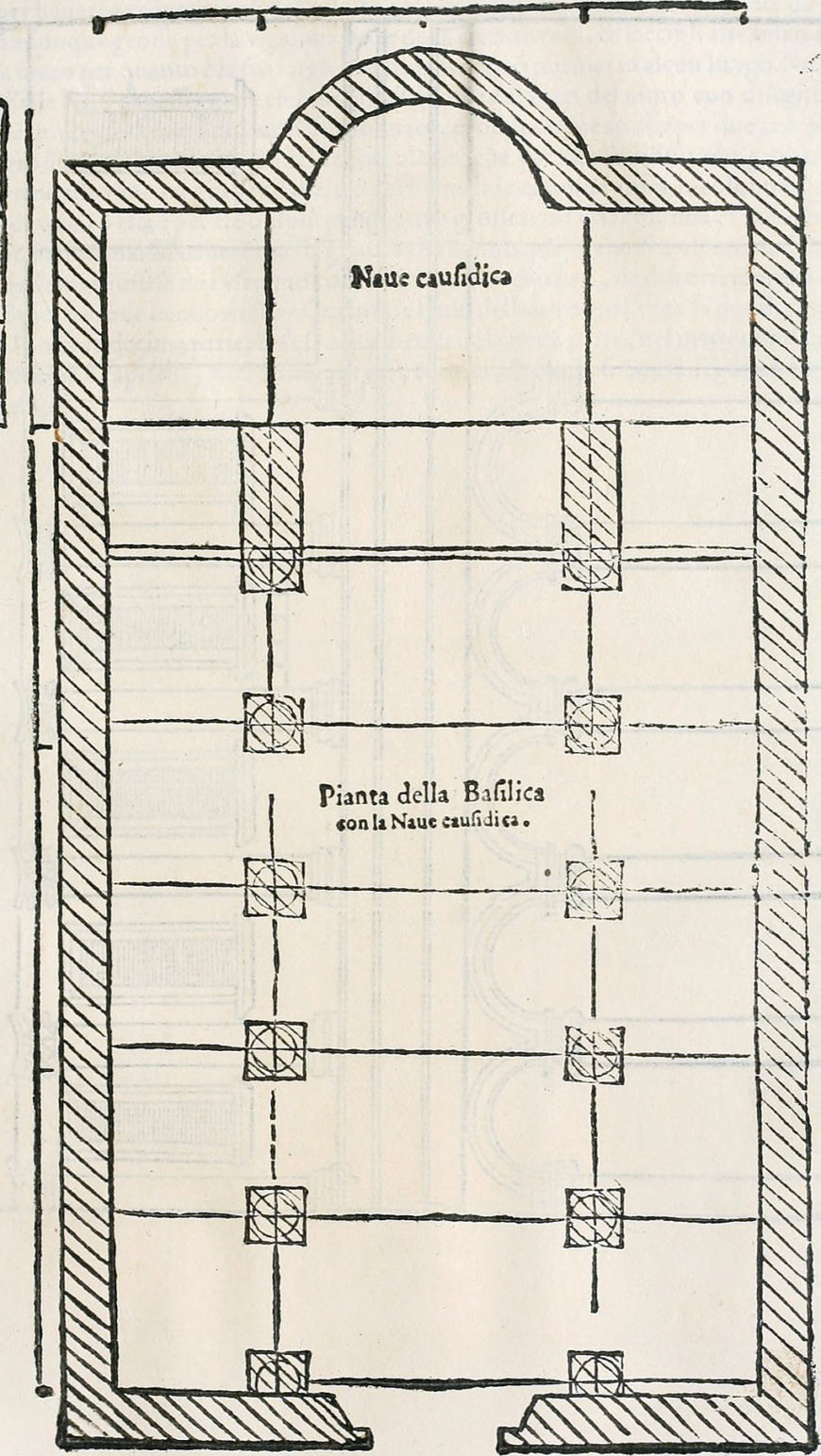

Other architects, like Francisco Becerra, Francisco Gutiérrez, and Pedro López Florín, also settled in Puebla in the latter part of the 16th century. Becerra is credited with designing the cathedral’s layout, an impressive edifice characterized by its classical ornamentation that has certain stylistic and formal parallels with Philip II’s El Escorial. One of the most important elements in Puebla’s cathedral, which is related to the classical tradition, is the building’s form, which is called a basilical plan. A basilica was a building type that harkened back to the ancient Romans. They used basilicas as public buildings where courts of law and other official affairs were conducted. The Christian tradition adopted the idea of a basilica as the notion of a large, religious building that was fit for congregating large amounts of people and carrying out processions throughout them. By the renaissance era, a basilica plan was a building model employed for important Christian religious buildings, notably for cathedrals, which had a series of ample corridors (called naves) separated by rows of columns. In Spain, many cathedrals had been built following this scheme, and Becerra adopted the basilical plan when designing Puebla’s cathedral. Relatedly, Alberti’s treatise included a model for designing a basilical building.

Becerra also had a hand in other important civic buildings, like the private residence of the Cathedral Chapter’s Dean, a cleric named Tomás de la Plaza. His residence, today known as Casa del Deán (The Dean’s House), is one of Puebla’s most relevant works of classical architecture from the 16th century.

Important religious buildings in Puebla from the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries, such as colleges, convents, or parish churches, were often designed in the classical canon. The main façade of the Santo Domingo convent is a good example of the appreciation the religious orders in this city had for classicism. The façade is severe and purist in its classicism, noted in the lack of ornamentation and adherence to the rules of classical composition of elements such as columns and architraves. The material, a dark grey basaltic stone, adds to the sense of sobriety.

Main façade of the Templo de Santo Domingo

Architectural treatises in Puebla

A significant number of architectural treatises in Puebla’s historical libraries demonstrate how individuals learned about knowledge of classical architecture in Puebla. The Palafoxiana Library and the Lafragua Library were both established in the late 16th century and have volumes by Vitruvius, Alberti, and Serlio.

The power that renaissance architectural treatises had as disseminators of visual messages was nowhere as powerful as in the Americas, where European colonizers encountered unimaginable expanses of territory that they set out to conquer and colonize. The colonization process undertaken by the Spanish in New Spain and elsewhere, involved the shaping of the built environment along colonial ideals, and classical architecture, in that sense, played a crucial role in cities like Puebla.

Classicism in the visual arts

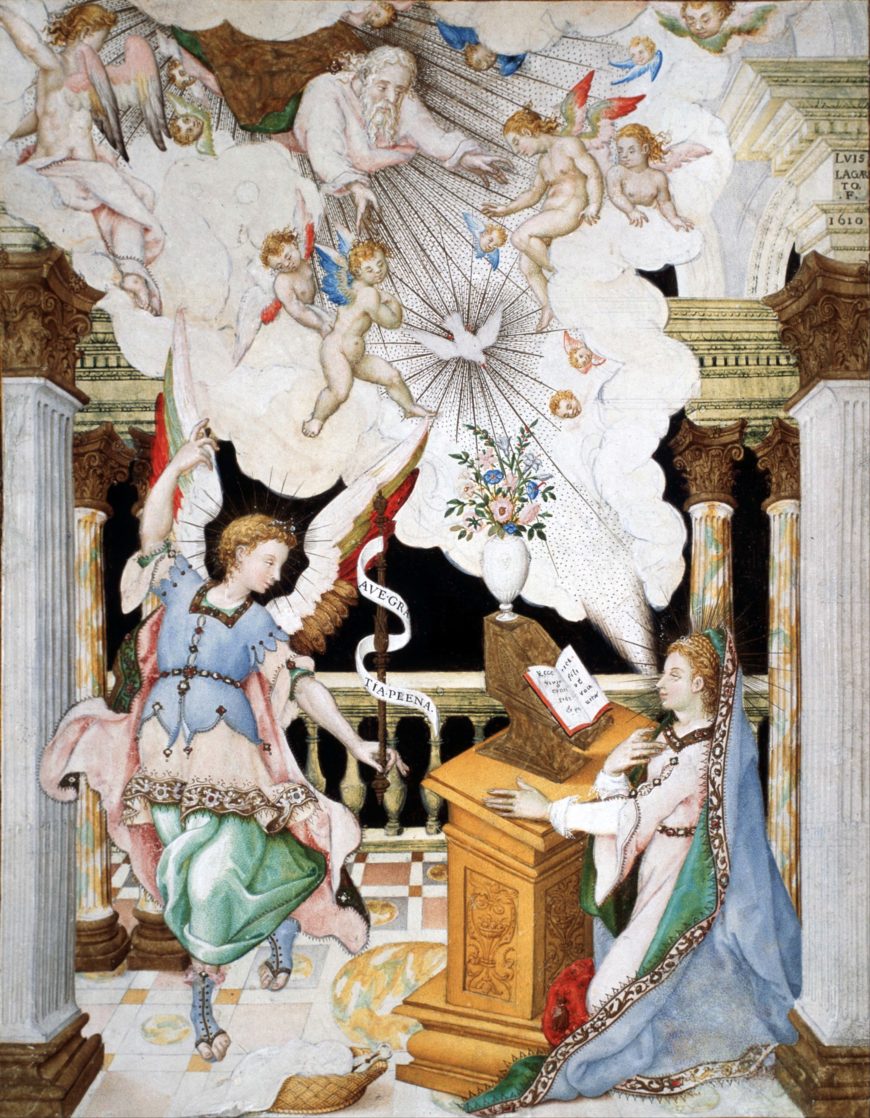

Luis Lagarto, Adoration of the Shepherds, 1610, gouache on parchment with gold leaf, 25.4 x 20.3 cm (Denver Art Museum)

The reception and popularization of the classical architectural language in Puebla is also observed in pictorial arts, such as paintings by Luis Lagarto. Born in Andalusia, Spain, Lagarto migrated to New Spain and was active in Mexico City and Puebla. He received a commission to illuminate the choir books for Puebla’s cathedral in 1600, spending more than a decade on this project. While he was in Puebla, he painted religious miniatures, including The Annunciation and Adoration of the Shepherds, both carried out sometime around 1610.

Both of these images display intricate architectural environments by the artist, who paid attention to carefully designed classical architectural backdrops. In The Annunciation, the Archangel Gabriel meets the Virgin Mary, while above them, a window into heaven opens with God and a cohort of angels watching the scene. All of this drama unfolds in an intricate and elegant architectural space, in which marble Corinthian columns are topped by a finely decorated frieze. Lagarto’s attention to classical architecture in this work is outstanding, and his depiction of entablatures, Corinthian pilasters, columns, a tiled marble floor, and a technically accomplished perspective reveal an undeniable visual proficiency regarding architectural classicism. The tendency to employ classical architectural backdrops would continue throughout the 17th century.

Reframing our understanding of the renaissance

The importance of classical architecture to Puebla’s 16th- and 17th-century colonial history helps to reframe our understanding of the renaissance as it has been traditionally understood—namely, as a northern Italian phenomenon whitewashed by notions such as the flowering of philosophy, education, and artistic innovation via an emphasis on individual agency and creativity. In the context of the Spanish colonial Americas, as we have seen with the case of Puebla, renaissance ideas and forms were part of a colonial endeavor that aided colonizers in implementing a cultural program that asserted their values over Indigenous ones. The concept of classical architecture and urbanism in Puebla was part of a broader colonial enterprise that urges a revised, expanded, or altogether redefined understanding of the renaissance.