Crown of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, known also as the Crown of the Andes, c. 1660 (diadem), c. 1770 (arches), gold and emeralds, Popayán, Colombia, body diameter 34.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Crown of the Andes backstory

The Crown of the Immaculate Conception is a complex object. There is so much that one can discuss, from Catholic religious performances and dressing statues to Spanish colonialism and the long history of emerald and gold mining in Colombia. It is remarkable that it survives until today, given that many other crowns and metal objects that dressed Catholic religious statues have been melted down over time.

There is also an opportunity to talk about the broader life of the Crown: where it was made, where it moved, and why it is now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. If you look at the object entry for the Crown on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website, you will notice the provenance information noted as this:

Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, Cathedral of Popayán (Colombia); Tomás Olano y Hurtado, Popayán [syndic of the confraternity, granted permission to sell the crown by Pius X in 1914]; his son, Manuel José Olano, Popayán, until 1936; Warren G. Piper, Chicago, until 1938; Oscar Heyman & Brothers, New York, until 1963; Sotheby & Co., London, November 21, 1963; sold to Asscher Diamond Company, Amsterdam, acting on behalf of Oscar Heyman (1888–1970), New York; his daughter, Alice Heyman, New York, 1973–2015; sold to MMA.

But what does that mean?

After the Crown was made, its caretakers were members of the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception at the Cathedral of Popayán. In the early 20th century, Pope Pius X granted permission to the confraternity to sell the Crown to raise funds for the Cathedral, though this decision was not agreed upon nor considered desirable by all members of the broader church community. Still, it was sold, and by 1936 it was in private hands in the United States, then owned by Warren G. Piper in Chicago. Piper was a gem dealer who undoubtedly found the many emeralds on the Crown of considerable interest. He was the one who provided the nickname: the “Crown of the Andes,” and who built up its acclaim in the U.S. by having the Crown go on tour; he also rented it for events. It would be displayed at World’s Fairs and other public spaces, and was even displayed in the window of Macy’s Department Store in New York City and also at General Motors in Detroit. Besides Piper, the Crown would pass through several other hands before eventually being put up for auction in 1995 by Christie’s; it did not sell at that time (though the Colombian government did attempt to buy it back at this time).

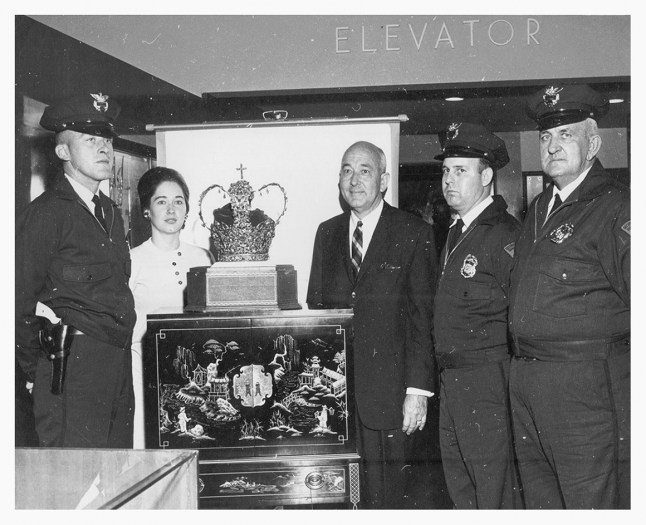

The Crown of the Andes is exhibited in Bromberg’s jewelry store, Alabama, 1958 (photo: Bromberg’s archive)

Between 1973–2015 the Crown was with the Heyman family of New York, before it was sold to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It had come to The Met’s conservation lab a couple of years earlier because of the Crown’s state: it was collapsing. There, it underwent extensive conservation efforts to repair damage. Technical studies at this time helped to date the different components of the Crown. Currently, it is on display in the American Art wing at The Met, surrounded by other paintings and silver and gold objects from South America during the period of Spanish control (what is called the viceregal era). Whether it should remain in the collection of The Met is debated, and there are calls, by some parties, for it to be restituted to Colombia, based on questions related to the legality of the initial sale.

Additional resources

Crown of Andes arrives for World’s Fair (1939)

Introduction to the Spanish viceroyalties

Object page from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Where are the boundaries of American art?” On the Crown of the Andes

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”crownandes,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:06] We’re at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, in a gallery devoted to the art of the Spanish Americas, and we’re looking at several paintings of the Virgin Mary with these elaborate golden crowns. And we’re standing before an actual crown that is gold and covered in emeralds.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:24] This is actually five pounds of gold and more than 400 emeralds. This is a fabulous object, but also displays the incredible workmanship of the craftsmen who made this.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:38] This is the “Crown of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception,” from Popayan, in what is today Colombia, and the crown has an interesting story, largely because of the materials it’s made of but also because it was constructed over several different periods of time.

Dr. Harris: [0:55] At this moment in history when the crown is created, the country we know today as Colombia and adjacent countries were part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada. This is a crown that was not made for an earthly ruler, but for the Virgin Mary, the Queen of Heaven. A sculpture, in fact, that was kept at the cathedral in Popayán.

[1:15] This crown would have dressed the Virgin Mary when she was taken out on a procession.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:19] This is what we could call a votive crown, or a votive offering. It was gifted to the Virgin at Popayán after she supposedly helped to protect the city against sickness, against smallpox, and other things like famine.

[1:34] Members of the community came together and paid to have this crown made as a sign of their thanks, and as a way of demonstrating their piety, their reverence for the Virgin. This would have been one of many objects gifted to this particular statue of the Virgin Mary. This was common in the Spanish Americas, as well as in Spain and other parts of Europe, to dress sculptures.

Dr. Harris: [1:59] It’s not surprising that at the very top of the crown we see an orb, which is a symbol of royal power, and on top of that a cross, so this idea of Christ’s dominion on earth.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:09] Then of course his mother is the Virgin Mary, and she is the Queen of Heaven, which is why she wears a crown to begin with. The original portion of the crown dates to probably the early 17th century, and that is the cross and the orb.

[2:24] The diadem that’s at the bottom dates to the mid- to late 17th century, and then the arches date to the later 18th century. What we’re seeing is a crown that was important for the Virgin of Popayán, that people continued to add to it rather than, say, melting it down and creating something else.

[2:42] When you look closely at the diadem, we see these foliate designs — what look like leaves — and floral designs that are intertwined in this intricate design around the base. Then, we have clusters of emeralds together that almost give the impression of abstracted flowers.

Dr. Harris: [2:57] The diadem was created using a technique called repoussé. It was hammered from behind to create the volumes that we see in the gold and the patterns.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:08] We know from artistic and scientific analysis that the arches were made using a different process, which helps us to date them to a later period.

[3:17] If you’re looking at it, you can see some of those subtle differences in the way that it’s been fashioned. At the same time, it does give the impression of this complete whole, even though these different parts of the crown were made at different periods of time.

Dr. Harris: [3:31] This was part of a ensemble for the Virgin on special occasions. We can imagine her also dressed in pearls and silver.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:41] She would be gifted luxurious clothes and other types of items. This is a crown that she would not have worn on a daily basis.

[3:48] If you had gone to the cathedral, you wouldn’t have seen her wearing all of these things at once. They would have been placed on her for special feast days, especially Holy Week, when the sculpture of the Virgin of Popayan would have been processed through the streets.

[4:02] Keep in mind that here in the museum, we’re seeing this crown static. It’s not moving. It’s behind a glass case. But when it was placed on the sculpture that was moving, it would have been activated and animated in different ways. Hanging from some of the arches at the top, we see emeralds that would have moved as the Virgin was processed.

Dr. Harris: [4:21] This is an object that held importance for a community over a long period of time. We get a sense of how it was used when we look at paintings of statues of the Virgin Mary also wearing a crown.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:35] If we talk about the crown in terms of its production, the materials, and the labor that went into making it, we could talk about how goldworking and emerald mining has a very long history in Colombia that predates the arrival and invasion of the Spaniards in the 16th century.

[4:53] In this area of Colombia, there were many Indigenous populations that for a very long time made objects in gold and mined emeralds. This longer history of gold extraction predates the Spaniards.

Dr. Harris: [5:08] As does the use of emeralds.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:10] These were already local traditions that were radically transformed with the arrival of Europeans and the subsequent conquest that occurred. We know from early colonial sources [that] emerald mining was very time-consuming, very difficult and challenging work.

[5:26] It is typically Indigenous laborers who are doing that mining, but as the result of epidemics, of overworking, you also have an influx of enslaved Africans work in the mines.

[5:38] Colombia is today known for having the world’s finest emeralds. They are this beautiful, rich green. It is part of what made the region that included Popayán so wealthy throughout the Spanish colonial period.

Dr. Harris: [5:51] These emeralds were making their way across the world to the Mughal Empire in India. There was a huge market for emeralds globally.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [6:01] The mining of gold and emeralds was really important for that global flow of materials. We do have to remember the human cost of producing something like this, as well.

[6:10] [music]