All-T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, 1450–1540 (Inka), camelid fiber and cotton, 90.2 x 77.15 cm (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.)

The Inka were masters of statecraft, forging an empire that at its height extended from modern Quito, Ecuador to Santiago, Chile. One of the engines that drove the empire was the exchange of high-status goods, which helped to secure the reciprocal but unequal economic and power relationships between the Inka and their subjects. Precious materials such as Spondylus shell from the warm waters of coastal Ecuador or gold from remote mountain mines were shaped into high-status objects. These were given to local leaders as part of a system of imposed obligations that gave the Inka the right to claim portions of local produce and labor as their due. Along with jewels, political feasts and gifts of finely-made textiles would also cement these unequal relationships.

Textiles and their creation had been highly important in the Andes long before the Inka came to power in the mid-15th century—in fact, textile technologies were developed well before ceramics. Finely-made textiles from the best materials were objects of high status among nearly all Andean cultures, much more valuable than gold or gems. The All-T’oqapu Tunic is an example of the height of Andean textile fabrication and its centrality to Inka expressions of power.

Weaving on a backstrap loom, Diego Rivera, Weaving, 1936, tempera and oil on canvas, 66 x 106.7 cm (Art Institute of Chicago) © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F.

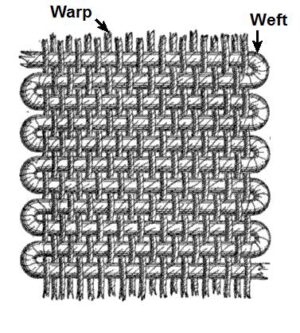

Diagram of warp and weft, (Alfred Barlow, Ryj, PKM, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The making of Andean textiles

Weaving in Andean cultures was usually done on backstrap looms made from a series of sturdy sticks supporting the warp, or skeletal threads, of the textile. A backstrap loom is tied to a post or tree at one end, while the other end is attached to a strap that passes around the back of the weaver. By leaning forward or tilting back, the weaver can adjust the tension on the warp threads as he or she passes the weft threads back and forth, creating the pattern that we see on the surface of the textile. By the time of the Inka, an incredible number of variations on this basic technique had created all kinds of textile patterns and weaves.

T’oqapu (detail), All-T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, 1450–1540 (Inka), camelid fiber and cotton, 90.2 x 77.15 cm (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.)

The two main fibers spun into the threads of the tunic came from cotton and camelids. Cotton plants grew well on the Andean coast in a variety of natural colors. Camelids thrived in the highlands (this includes the wild guanacos and vicuña and their domesticated brethren, the llama and the alpaca). Most Andean camelid-fiber textiles were made with the silky wool of the alpaca. Animal fibers are more easily dyed than plant fibers, so when weavers wanted bright colors they most commonly used alpaca wool. The All-T’oqapu Tunic is made of dyed camelid wool warp over a cotton weft, a common combination for high-status textiles.

Collecting, spinning, and dyeing the fibers for a textile represented a huge amount of work from numerous people before a weaver even began their task. Some dyes, like cochineal red or indigo blue, were especially prized and reserved for high-status textiles. Cochineal dye comes from the bodies of small insects that live on cacti, and it takes thousands of them to make a small amount of dye. Indigo dyeing requires a high level of technical skill and a large investment in time. Red- and blue-dyed textiles were not only beautiful, they also represented the apex of the resources needed to produce them and the social and political power that commanded those resources.

T’oqapu (detail), All-T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, 1450–1540 (Inka), camelid fiber and cotton, 90.2 x 77.15 cm (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.)

In the Inka empire, textiles were produced by a number of groups, but the finest cloth, called qompi in Quechua (the language of the Inkas), was produced by acllas (“chosen women”), women who were collected from across the empire and cloistered in buildings to weave fine cloth. The acllas also performed religious rituals and made and served chicha (corn beer) at state feasts. These women spun, dyed, and wove fibers that were collected as part of the Inka taxation system. The textiles they produced were then given as royal gifts, worn by the royal household, or burned as a precious sacrifice to the sun god, Inti. The threads in the All-T’oqapu Tunic were spun so finely that there are approximately 100 threads per centimeter, making for a light, strong weave. It was traditional to weave garments in a single piece if possible, as cutting the cloth once it was off the loom would destroy its spirit existence (camac), which formed as it grew on the loom. The All-T’oqapu Tunic is a single piece of cloth, woven with a slit in the center for the head to pass through, and folded over and sewn together along the sides with spaces left open as arm holes.

Iconography

The decoration of the tunic is where its name derives from. T’oqapu are the square geometric motifs that make up the entirety of this tunic. These designs were only allowed to be worn by those of high rank in Inka society. Normally, an Inka tunic with t’oqapu on it would have a band or bands of the motif near the neck or at the waist. Individual t’oqapu designs appear to have been related to various peoples, places, and social roles within the Inka empire. Covering a single tunic with a large variety of t’oqapu, as seen in this example, likely makes it a royal tunic, and symbolizes the power of the Inka ruler (the Sapa Inka). The Sapa Inka’s power is manifest in the tunic in several ways. Firstly, its fine thread, expert weave, and bright colors signify his ability to command the taxation of the empire, access to luxury goods like rare and difficult dyes, and the weaving expertise of the acllas. Secondly, among the t’oqapu in the tunic is one pattern than contains a black and white checkerboard. This was the tunic pattern worn by the Inka army, and shows the Sapa Inka’s military might. Lastly, the collection of many patterns shows that the Sapa Inka (which means “unique Inka” in Quechua) was a special individual who held claim to all t’oqapu and therefore all the peoples and places of his empire. It is a statement of absolute dominion over the land, its people, and its resources, manifested in an item that is typically Andean in its material and manufacture.