Attributed to Francisco Becerra, façade of the Casa del Deán, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

Renaissance architecture and humanist culture in Puebla, Mexico

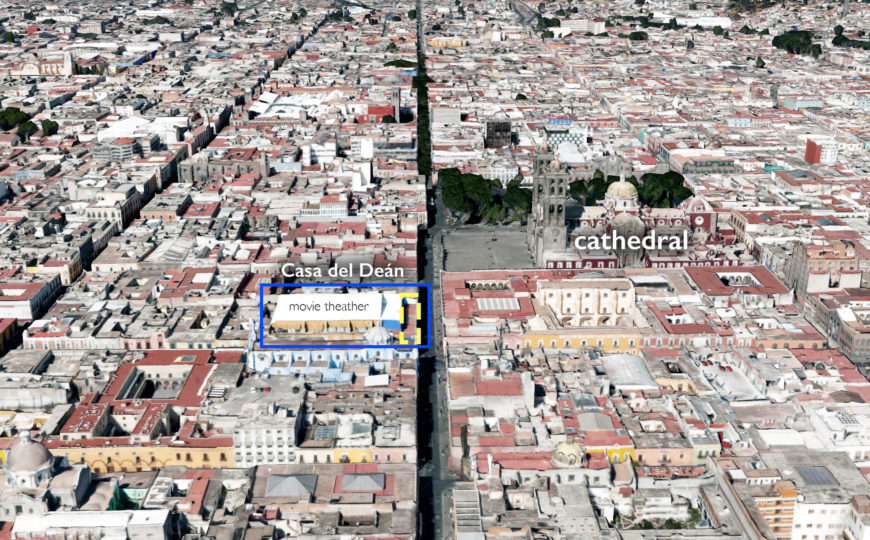

Close to Puebla’s cathedral and central square stands the once palatial residence known as the Casa del Deán or The Dean’s House. It was built around the year 1580, but most of the residence was demolished in 1953 to make room for a modern cinema house. Thanks to preservation activists, a fragment of the palatial residence survived—the façade and two upstairs rooms that contain a fascinating mural program, including elaborately dressed figures riding on horseback in a procession that takes place amongst rolling hills, patches of woods, bodies of water, mountains, and hamlets.

The Triumph of Chastity, murals of the Casa del Deán, Hall of the Triumphs, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

What remains of the residence is an outstanding example of renaissance architecture and murals made in the viceroyalty of New Spain. The building and murals also speak to the importance of renaissance humanism in the city after the Spanish conquest of surrounding lands in 1521 initiated waves of evangelization and colonization. Renaissance humanist ideas were important to some of the Spanish colonizers, as they believed Humanism, which was the study of Classical literature and sources, represented some of the outstanding traits of European and Spanish civilization. Tomás de la Plaza was known to be a humanist, a person who studied classical literature and culture, which explains his choice of the classical style for his residence.

With Spanish colonization underway, wealthy Spanish colonizers adopted the urban palatial residences found in Italy and Spain. Such palaces were built for high-ranking clerics and even some Indigenous noble families who enjoyed privileges for having fought alongside Spanish forces against the Mexica. Residences of the elite class formed part of the urban fabric in towns such as Puebla, where the religious and civil buildings designed along classical (ancient Greek and Roman) lines embodied the concept of urbanitas, or urban refinement and decorum. Spanish colonizers viewed the city as the site of their “civilizing” efforts.

While the facade displays some Classical elements, such as the pediments over the windows and doors, others, like the tracery on the windows on top, are of medieval origin. Juan Guas, Palacio del Infantado, 1480, Guadalajara, Spain

Like their prototypes in Italy and Spain, these renaissance palaces were used to to flaunt the magnificence and political weight of the urban elite. In Spain, while many palaces display a classicizing renaissance style, there is also the influence of plateresque, mudéjar, and gothic ornamentation.

The facade of Casa de Montejo, 1540–50, Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico. The facade displays Plateresque motifs, identifiable in the intricate lace and vegetative ornaments, mixed with classical attached columns and pilasters. Of note is the violent character of the sculptures representing Spanish conquistadors standing on disembodied heads, a symbol of colonial subjugation. The Montejo family crest of arms is visible at the center of the upper body. (photo: Inri, CC0)

The urban palaces built in New Spain likewise displayed a mixture of classicizing, plateresque, mudéjar, and gothic ornamentation on their façades. Few examples of those palacios from the 16th century remain in present-day Mexico, and one of the most remarkable examples is the Casa del Deán.

Map of Puebla showing the location of the Cathedral and the Casa del Deán. The yellow box is what remains of the Casa today (© Google)

An urban residential palace in Puebla

The Spanish-born, high-ranking cleric named Tomás de la Plaza was the Dean of Puebla’s Cathedral Chapter and held important administrative roles. The design of the Dean’s House façade is attributed to the Spanish architect Francisco Becerra, who had come from Spain to design buildings that signaled the Spanish Catholic presence, including Puebla’s impressive new cathedral—a project De la Plaza was also involved with. Becerra was well-trained in classically-informed architecture, which he had practiced since he was a young man in his native Extremadura.

Attributed to Francisco Becerra, façade of the Casa del Deán, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

Sebastiano Serlio, Book 2 of The Book of Architecture, published by Jean Barbé, 1544 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

De la Plaza (the Dean) may have asked Becerra to remodel an existing building he had acquired. Becerra’s design for the entry portal possesses a sense of rhythm and repetition that lends the building a coherent sense of order (although it has been disrupted in its present state).

The balconies we see today were originally windows and the lower floor entries have changed in their dimensions and forms (see hypothetical reconstruction).

A hypothetical reconstruction of Casa del Deán in the late 16th century. Of note are the windows, which were transformed into balconies and the tower seen on the left side of the elevation. The ground floor entries and windows have also been extensively altered over the centuries (drawing by Trevor Wood, hypothetical reconstruction by Juan L. Burke)

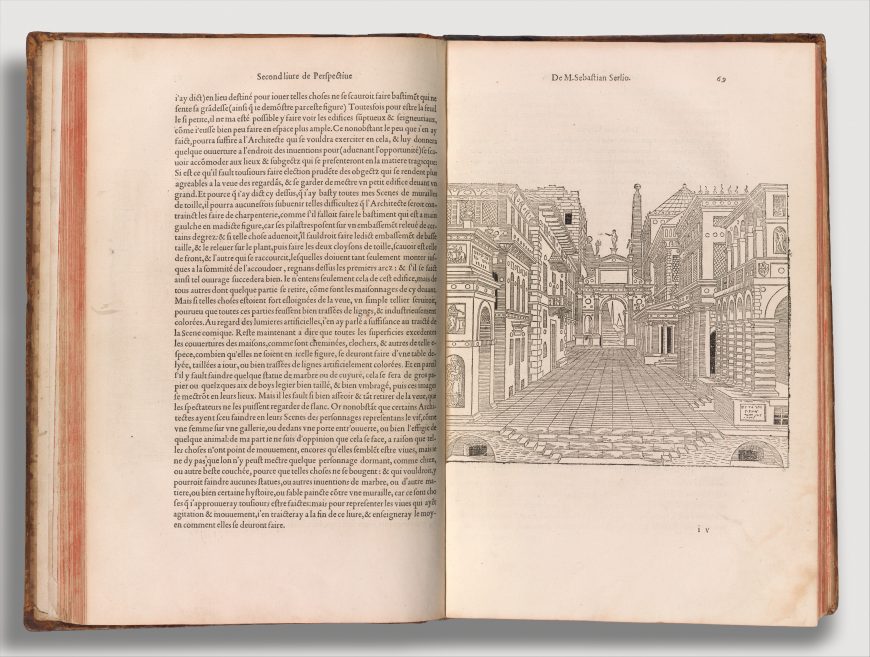

The palace also demonstrates the important role that classical architectural principles had among some elite, intellectual Spaniards who participated in the colonial enterprise. The residence portal of the Casa del Deán reminds us of Sebastiano Serlio’s popular 16th-century treatise, The Book of Architecture, that borrowed from classical architecture and ideas, and which would influence a great deal of architecture throughout the Spanish Americas.

Attributed to Francisco Becerra, façade of the Casa del Deán, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

The lower level of the portal consists of an entry flanked by two engaged Doric columns on pedestals. The columns are fluted and sit below a robust entablature, which carries the second-story balcony. This second story balcony is fitted with a pair of rusticated jambs and lintels that are flanked by engaged and fluted columns with Ionic capitals. These columns support a cartouche of Tomás de la Plaza’s family coat of arms (now partially missing). The frieze displays the words Plaça Decanus (Plaza, the Dean), and the building’s year of completion, 1580. Flanking the upper-level balcony are two ogee windows, characterized by having a cusped lintel. These windows are complemented by classical pediments above them. Each pediment at Casa del Deán displays a sculpted scallop shell at its center—a possible sign of devotion, on behalf of de la Plaza, to St. James, the patron saint of Spain. Each window is crowned by an elegant finial.

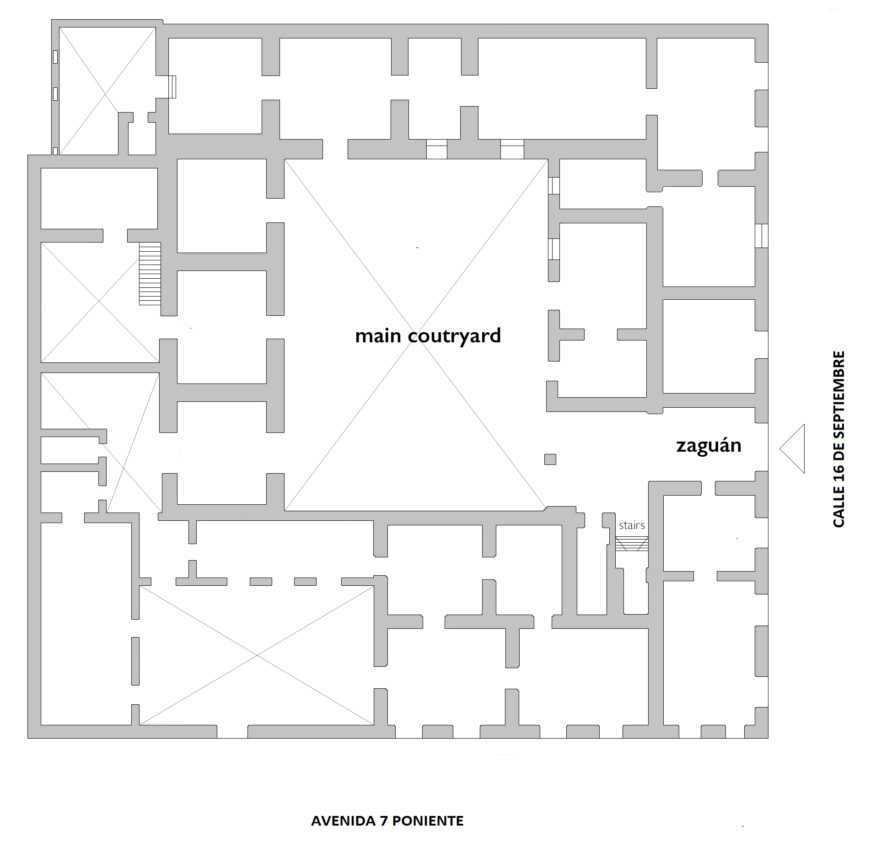

Plan of the first floor of the Casa del Deán (before the 1953), 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (plan adapted from: YoelResidente, CC BY-SA 4.0)

From this doorway, a person walked into a covered vestibule space (known in Spanish as zaguán) that led into an open courtyard, encircled by a series of rooms on two levels. At Casa del Deán, the stairs were at the left hand of the main entry. The lower level was used for storage, to house horses, and for service spaces; sometimes lower-level rooms were rented out to shopkeepers or artisans. The upper level was known as the piano nobile, an Italian term that designates the living spaces of a residence. It included bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and sometimes even a small chapel. At Casa del Deán, the only two extant rooms were probably a living or dining room, and another one may have been a a study room.

Murals of sibyls on horseback holding standards. From left to right the sibyls are Cumana, Delphica and Hellespontica. North wall, Hall of the Sibyls, the Casa del Deán, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

The Casa del Deán’s murals

Besides its architecture, the most intriguing aspect of the Casa del Deán is its murals. In each of its two surviving halls, there is a cycle of mural paintings done in tempera, each one with a specific program and visual imagery. The Hall of the Sibyls is based on the figures of the Greek oracles that, during the renaissance period, were understood as pre-Christian prophetesses who predicted the coming of Jesus. The sibyls are depicted at Casa del Deán in a processional cycle, all of them riding on horseback. in the ancient Hellenic world, the sibyls were considered to be itinerant, which means they traveled from town to town performing their divinations, and this probably explains the reason they were represented on horseback at Casa del Deán. Each sibyl is holding a standard (type of flag) and a symbol or emblem of their prophecies. All are elaborately dressed, and their procession takes place against a picturesque landscape of rolling hills, patches of woods, bodies of water, mountains, and hamlets. These pastoral environments were referred to as a locus amoenus, a phrase in Latin meaning “beautiful place,” a common setting for classical literature and art in the pre-modern era. Framing the sibyls’ procession, at the top and bottom, are two elaborate horizontal friezes, in which putti mingle with birds, fruits, flowers, and vines, a veritable representation of a garden of delights.

Each of of the sibyls’ names are inscribed next to them, although some names became illegible over time, and their identities are now unclear. There are twelve visible sibyls in total, and each one carries a standard revealing their prophesies, which are all related to the coming, life, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The sibyl that starts the procession is called the Synagogue sybil, so-named because she represents the Old Testament. She is followed by the Erithrean sybil, who prophesied the Annunciation, and behind her is the Samian sybil, who prophesied the Nativity, and so on, ending the procession with a sybil whose name has been erased, who most likely prophesied the Ascension of Christ to the heavens.

The left (south) wall shows the Triumph of Eternity, the center (west) wall shows the Triumph of Love, and the right (east) wall, not visible here, shows the Triumph of Chastity. Murals of sibyls or horseback holding standards, Hall of the Triumphs, the Casa del Deán, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

The other hall contains a representation of the narrative poem, Triumphs (c.1351) by the Italian poet and humanist Petrarch, that was much admired in the late medieval and renaissance eras. The essence of the poem spoke of a transition from sin to Christian salvation. Petrarch populated the poem with a series of allegorical figures—Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, Time, and Eternity—that later artists often represented as a series of triumphal carts, pulled by horses, stags, or fantastical creatures such as unicorns. The murals in this room display a version of those allegorical figures in their carts.

The triumph represented in the figure above, a chariot pulled by two white unicorns, represents the Triumph of Chastity or Virtuosity. Unicorns were, in the European medieval period, considered to be a symbol of virtuosity too, an animal which was believed to be real but elusive and of a shy nature. The chariot is driven by a young female. The young woman is Laura, the love of Petrach to whom he dedicated the Triumphs. Laura is also, in this case, the embodiment of virtuosity or chastity. The women behind the chariot carry a palm in their hands, a symbol of victory in the ancient world. The embodiment of chastity carries a palm too, together with a torch, a symbol in the ancient world of a condition of enlightenment or purification.

The triumphant chariot driven by Laura can be seen running over a pair of people, a man dressed as a monk and a woman. The monk could represent Petrarch himself, who was a canon, a post of lesser rank in the Catholic Church. Petrarch made a vow of chastity but was still believed to have fathered two children. The woman in the picture could be interpreted as Eve herself, a symbol of the loss of virtuosity in Christian symbolism. This mixture of pagan (ancient classical) and Christian symbols interacting together is an interesting aspect of the representation of the Triumphs at the Casa del Deán.

Murals of the Casa del Deán, Hall of the Sibyls, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

Some interesting aspects of the murals are contained in the details and the backgrounds. For instance, in both halls the murals depict vistas that are reminiscent of Northern European landscape painting.

Paired monkeys, murals of the Casa del Deán, Hall of the Sibyls, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Juan Luis Burke)

Monkey scribe, murals of the Casa del Deán, 16th century, Puebla, Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

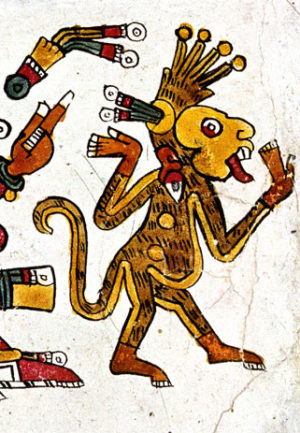

However, even if at first glance the murals at the Dean’s House are reminiscent of European art, details reveal the Indigenous background of the artists. For one, many of the animals depicted in the mural cycles are native to the Americas, such as monkeys, jaguars, opossums, coyotes, and javelinas, and they reveal traces of Amerindian iconography.

In the Hall of the Triumphs we find further evidence of the Indigenous origin of the artists, such as representations of animals in cartouches (with anthropomorphic attributes), which are shown in a series of roles, such as scribes, musicians, or dancers.

Interestingly, monkeys were held in very high regard by Mesoamerican cultures. The eleventh day of calendar was symbolized by a monkey and in some mythical narratives, like the Popol Vuh, monkeys were considered closely related to humans. In contrast, medieval Europeans considered monkeys to represent sin and debauchery. It is telling how, at Casa del Deán, monkeys are depicted carrying out human-like behaviors and in the friezes are seen with the characteristically Mesoamerican symbol of the spoken word (which looks like a little cloud close to the character’s mouth). Additionally, the monkeys depicted at Casa del Deán share many similarities with Mesoamerican depictions of these animals in pre-Hispanic or early post-Conquest documents, like the Borgia Codex.

We also see the presence of Indigenous objects, such as a jaguar depicted as a warrior holding a macuáhuitl (an Indigenous mallet used as a weapon) and a typical pre-Hispanic round shield.

Penny Morrill has argued that the artists at work in the Casa del Deán might have trained at a Franciscan monastery in the Puebla-Tlaxcala region. [1] De la Plaza, who arrived to New Spain at the age of 19, traveled the territories that comprise present-day Oaxaca and Puebla states extensively as a missionary, where he may have acquired an affection and appreciation for native cultures, which he subtly displayed in his home’s murals. Additionally, it is worthwhile to note that de la Plaza, like many educated colonialists, might have had access to prints, which were a common visual source utilized by Indigenous artists to recreate European aesthetics and visual forms.

An important architectural relic

The Casa del Deán responded to notions of magnificence and decorum (the idea that individual buildings contribute to the beauty and magnificence of a city), while reaffirming the social standing of the residence’s owner and the cultural values that he stood for. The murals in the residence’s private spaces also responded to the intellectual and theological concerns of de la Plaza. The influence of Indigenous artistic styles and the presence of native cultural symbols in the frescoes is important, because in colonial societies, the colonized groups—as was the case with the Indigenous peoples of Mexico—were not often allowed to flaunt or display their cultural values, most often deemed inferior and undesirable by the colonizers. On the other hand, the Casa del Deán testifies to the importance of renaissance classicism and humanist culture in New Spain, and Puebla in particular, as part of the belief system of the Spanish colonizers and the values they upheld in the cities they established in the Americas.