Vicente Albán, Noblewoman with a Black Slave, 1783, oil on canvas, 80 x 109 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Documenting American possessions

The paintings are linked to a series of expeditions ordered and sponsored by the Spanish crown to document the natural bounty of their American possessions. One of these, led by the Spanish naturalist José Celestino Mutis, set out in 1783 to document the Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada (modern day Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela). Mutis aimed to gather information about the local landscape in order to exploit its natural resources for commercial gain.

Alongside financial interest however, was scientific curiosity. The paintings have been celebrated as products of the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement of the 17th and 18th centuries also known as the “Age of Reason.” One popular scientific theory of the time involved the development of systems to classify flora and fauna using a system that came to be known as taxonomy. While Mutis focused on botanical illustrations (and produced thousands of them), he also commissioned a series of six paintings of human figures within the bountiful landscape which were sent to Spain as diplomatic gifts. These, the canvases by Vicente Albán, were born of a conjoined ambition to both classify and extract wealth from the local landscape and its people.

Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, Bathsheba at her Toilet, 1594, oil on canvas, 77.5 x 64 cm (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Exaggerated contrasts and white supremacy

Noblewoman with a Black Slave is labeled in the cartouche, “Señora Principal con su negra esclava,” which translates to “Noblewoman with her Black slave.” [1] When looking at the two women, our eye is immediately drawn to the striking contrast between the porcelain, ghostly white complexion of the Spanish woman as contrasted with the pitch Black skin of the African woman who stands behind her. Such contrasts between exaggeratedly white and Black skin has a long history in European painting, and can be seen strikingly in, for example, Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem’s Bathsheba at her Toilet.

In both paintings the artist constructs a polarized binary between the very dark skin of an “attending” figure and the whiteness of the powerful main subject. Such contrasts were tied to white supremacist notions about the perceived beauty of whiteness. By placing the two women side by side, the artist elevates the status of the Señora Principal vis-à-vis her beauty and power derived from her white skin which contrasts starkly with the dark skin of the enslaved woman. These inequalities are further seen in the dress. While certainly well dressed, the enslaved woman’s clothing pales in comparison to the gold, pearl, silk, and lace beladen Señora Principal. Furthermore, while we may be tempted to read the nice clothing and gold jewelry worn by the enslaved woman as evidence of some perceived social mobility, the system whereby humans were commodified as property celebrated the enslaver’s great wealth and benevolent ability to dress enslaved people well. While some enslaved people were able to procure their own fine clothing, the painting’s generalized tropes reveal nothing about the African woman’s treatment or opportunities for social advancement within the slave economy.

Vicente Albán, Yapanga, 1783, oil on canvas, 80 x 109 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

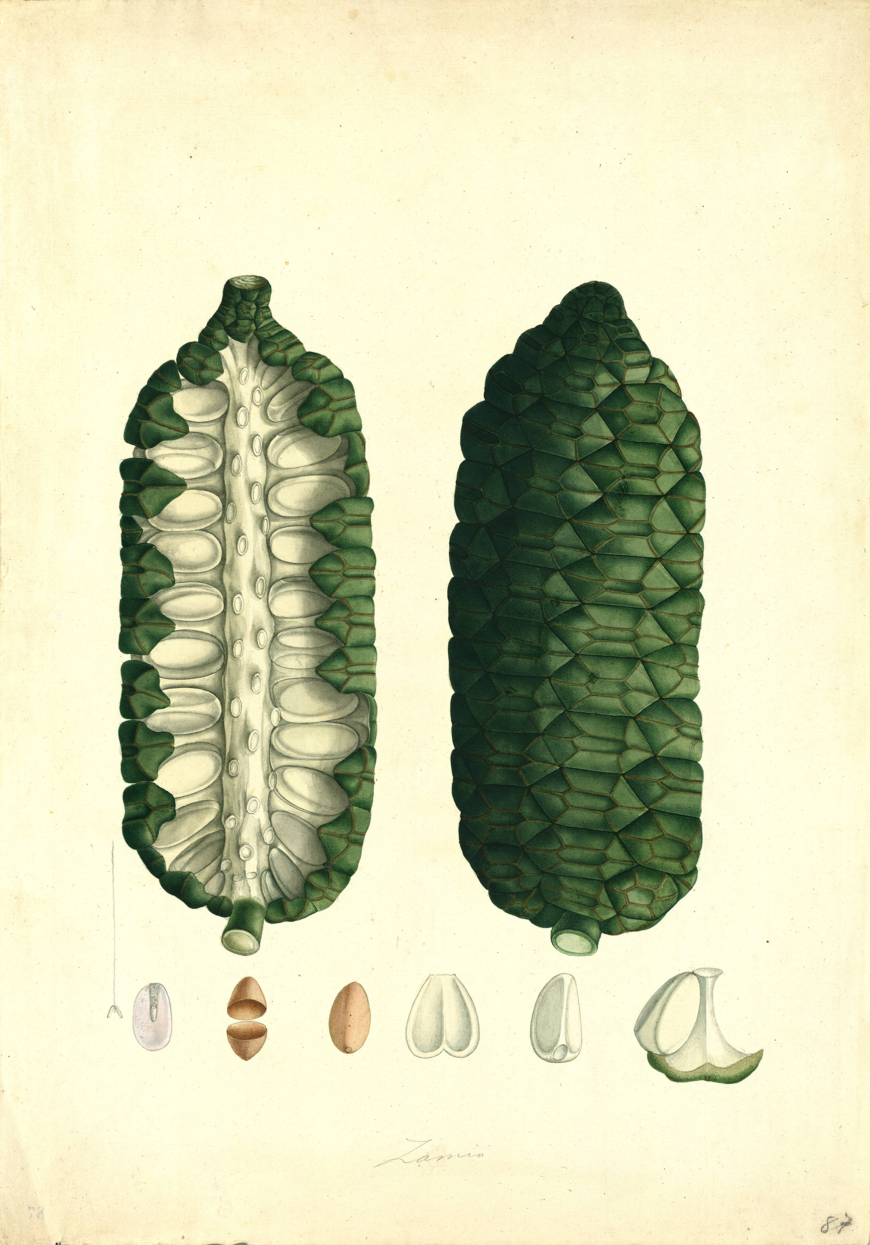

Botanical illustration from the expedition of José Celestino Mutis. Unidentified artist, Zamia cf. muricata, c. 1783–1816, 54 x 38 cm (Archivo del Real Jardín Botánico, Madrid)

The African woman in the painting also lacks shoes, a trope that we see repeated in another image from the series, the image of the Yapanga, a colloquialism for barefooted, which was also used in reference to sex workers.

Rather than the elaborate tiara of the Señora Principal, the yapanga wears a sombrero, indicating her lower social status. Interestingly, this painting contains both local and exotic specimens. Note the great attention paid to the produce which is depicted from various angles, at times exaggeratedly large for maximum visibility, and shown both whole and cut to expose their flesh. Albán’s rendering of the fruits and vegetables in this manner was likely inspired by botanical illustrations where specimens are rendered with great detail, from various angles, and at various points in the life cycle in order to provide maximum information for the purposes of scientific classification. Note the strawberry bush in the left middle-ground, laden with large ripe berries. Strawberries are native to Europe, but including them in the Quiteño landscape indicates that the landscape is fertile and ideal for a wide variety of crops, both local and imported. This was of particular importance for European audiences who were fascinated by the wealth and perceived exoticism of what they called the New World.

Left: Vicente Albán, Indio Principal, 1783, oil on canvas, 80 x 109 cm (Museo de América, Madrid); right: Vicente Albán, India in Festive Dress, 1783, oil on canvas, 80 x 109 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Left: Vicente Albán, Feathered Yumbo, 1783, oil on canvas, 80 x 109 cm (Museo de América, Madrid); right: Vicente Albán, Cargo Yumbo, 1783, oil on canvas, 80 x 109 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Apollo Belvedere (Roman copy of a Greek(?) original), original late 4th century B.C.E. marble, 2.3 m high (Vatican Museums, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Indios Principales contrast with the next two in the series: the Feathered Yumbo and the Cargo Yumbo. The yumbo refers to any number of Indigenous ethnic groups living outside of Quito and Guyaquil, commonly known as travelers and tradespeople. They were typically thought of as non-threatening and known for practicing long-distance trade. Yumbos were frequently associated with the urban marketplace. The Feathered Yumbo stands proudly in feathers and shells, holding both a spear and bow and arrow. His stance echoes that of the famed Apollo Belvedere, displaying a powerful and masculine classical pose that would have been familiar to a European audience. In contrast, the Cargo Yumbo crouches with the weight of his pack, the only one in the series in motion and engaged in physical labor.

While the first four paintings feature architectural plinths for their cornucopia of fruits, in the yumbo paintings, the exaggeratedly enormous fruits—including pineapples, bananas, and papayas—are placed within a natural environment, one that does not correspond to a perceived man-made space. In the Feathered Yumbo painting, they seem to almost spill out of the landscape, with only leaves behind them, while in Cargo Yumbo there is some reference to a platform, but one that, if man-made, appears to be crumbling and covered in vegetation. In this way, while all of the figures are painted outdoors, the artist places emphasis on the Yumbo as less civilized and closer somehow to nature.

While studying the images does provide the contemporary viewer with important information about the local landscape and its inhabitants, probably more saliently, it tells us about the ideas and concerns of the patron, artist, and intended viewer. Both scientific and political ambitions must be considered alongside the dazzling display of the bounty of the land in all its diverse and delicious splendor.

Notes:

[1] Although oftentimes likened to casta paintings, Albán is not interested in the familial model and resultant mixed-race offspring and instead focuses on singular local types (unlike the mixed-race families that were the focus of casta paintings).

Additional resources

This series at the Museo de América

Ilona Katzew, “Now on View: LACMA’s New Vicente Albán Paintings from Ecuador,” 2015.

Tamara Walker, “Black Skin, White Uniforms: Race, Clothing, and the Visual Vernacular of Luxury in the Andes,” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society, volume 19, number 2 (2017), pp. 196–212.

Sonya Wohletz, “Strange Fruit: Vicente Albán’s Quito Series And Local Ways Of Seeing In The Era Of Colonial Enlightenment,” La Península Ibérica, el Caribe y América Latina: Diálogos a través del Comercio, la Ciencia y la Técnica (Siglos XIX – XX) (Évora: Publicações do Cidehus, 2017).