Anonymous, Albina and Spaniard Produce Return-Backwards, casta painting, 1770, oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm (Banco Nacional de México, Mexico City)

In the foreground of a Mexican painting, a family perches on a rooftop. A woman gazes upwards at the heavens, while her son, whose dark skin contrasts with that of his mother, rests his hand on her shoulder. Her husband stands to her side peering out of a telescope at the landscape below, a scene of one of the most well-known urban spaces in the Spanish American world: Mexico City’s Alameda Central.

Francisco Clapera, De Alvina, y Español, Torna-atras (Albina and Spaniard Produce Return-Backwards), from set of sixteen casta paintings, c. 1775, 51.1 x 39.6 cm (Denver Art Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Alameda Central in a casta painting

This is a casta painting, a type of painting popular in 18th-century Mexico, typically produced in sets of sixteen. They depict mixed race couples and their offspring, seeking to classify the mixed races, or “castas” into socio-racial hierarchies. However, unlike most casta paintings, where the figures take up the majority of the composition, in this painting the family is subordinate in scale to the vast urban space that unfurls below. This is but one example of the many types of paintings depicting the famed public park that, while ostensibly open to all walks of life, was particularly celebrated by the city’s elite. By the late 18th century, guards were placed at its entrances to keep out people who were deemed unfit based on their manner of dress, race, and perceived social status. [1]

The casta painting reflects some of these hierarchies. The albina (identified as such from the title), a woman of one-eighth African and the rest Spanish blood, seems to beseech God for the fate of her family. Their status is in jeopardy upon the revelation of her Black African heritage, made visible by the appearance of her dark-skinned child, referred to in the cartouche as a tourna atras (literally, turn back).

Casta paintings reveal much about racial hierarchies in New Spain, and this one in particular relates to socio-racial hierarchies in an urban setting. While her husband surveys the park below, the family’s access to the elite social rituals that were enacted in the Alameda are in jeopardy in a creole society that clung to white supremacist categories heralded as markers of what they called limpieza de sangre—cleanliness of blood.

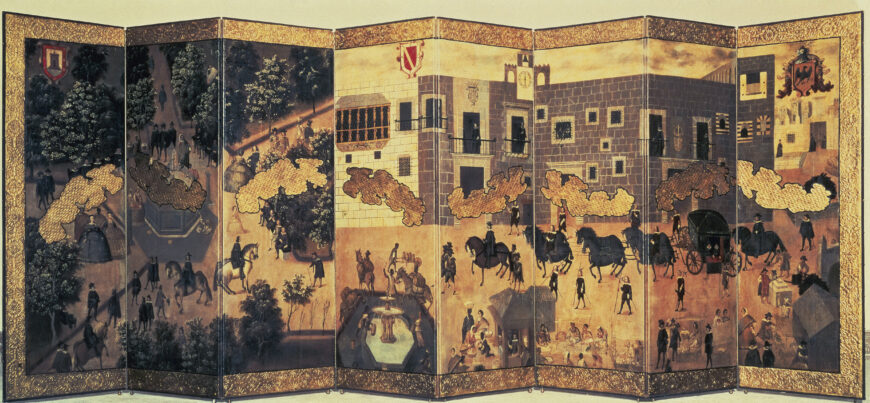

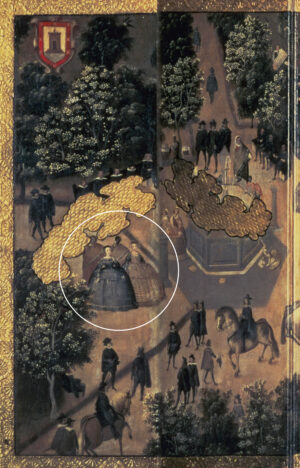

Biombo, View of the Palace of the Viceroy in Mexico City, c. 1676–1700, oil on canvas, 184 x 488 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Alameda portion (detail), Biombo, View of the Palace of the Viceroy in Mexico City, c. 1676–1700, oil on canvas, 184 x 488 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Alameda Central on a biombo

The Alameda Central was a place where, as English Dominican travel writer Thomas Gage described, elites came “…to see and be seen, to court and to be courted…” These elaborate social rituals are on display in another category of New Spanish painting, a biombo featuring a scene of the Alameda and Viceregal palace. This particular biombo collapses two separate civic spaces of the capital into a singular scene, despite their actual distance from each other. The Viceregal palace, which stretches the five panels on the right of the screen, was located in the center of Mexico City adjacent to the main square (or Zócalo). The Alameda, which occupies the left three panels, was on the outskirts of the city. Some scholars have suggested that there may be panels missing, but regardless the space has been collapsed in order to feature two important civic spaces as if they were in closer proximity to each other.

In the Alameda portion of the biombo, numerous figures are engaged in the social ritual of the paseo, or promenade, a social practice whereby elite members of society strolled through the park either on foot or horseback in order to see and be seen. Vendors often sold refreshments or trinkets, and the elites were served by servants or enslaved people.

At the far left beneath a golden Japanese-inspired cloud, four women walk beside a fountain. The two women in front wear guardainfante, a Spanish style hoop skirt. They appear to be Spaniards, or more likely creoles (Spaniards born in Mexico) who are trailed by two other women wearing much simpler dress as well as darker skin. These women are likely enslaved, and their presence in the paseo was a sign of the power and privilege of the creole women. Like the opulent dresses they wear, their human possessions are on display within the social rituals carried out in the Alameda.

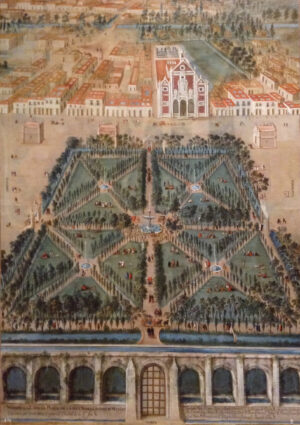

Attributed to Nicolás Enríquez, View of the Alameda Park and the Convent of Corpus Christi (Vista del Paseo de La Alameda y el convento de Corpus Christi), c. 1724, oil on canvas, 206 x 146 cm (Palacio Real de Madrid)

A painting of the park for the king

Similar scenes of the paseo are on display in Nicolás Enríquez’s View of the Alameda Park and the Convent of Corpus Christi, painted in 1742. This is one of a pair of paintings commissioned by the Viceroy as a gift to the Spanish king. The other painting in the series features an interior view of the Corpus Christi convent, which was founded for nuns who were largely from noble Indigenous families.

The convent is also seen prominently in the Alameda painting—a large classicizing façade in the right background beyond the park. The inscription at bottom indicates that the viceroy founded the convent and renovated the adjacent Alameda Central by planting trees and erecting fountains, acts which he hoped would impress the Spanish monarch and garner support for further development of the city.

Enríquez offers an almost cartographic rendering of the Alameda and its environs. Following the ideals of French landscape design, the natural environment of the park is controlled and orderly. Tree-lined lawns are bisected by paved pathways that radiate out from centrally placed fountains. Overall the park is orderly and symmetrical, displaying carefully manicured landscape design. Human figures are dwarfed by the massive scale of the scene, rendered with just small strokes of the brush due to their diminutive size within the composition.

Much like the other scenes of the Alameda, the landscape is punctuated by its human inhabitants who are cast according to socio-racial hierarchies. At the far right near the bottom of the scene a woman carries a tray or basket atop her head. She appears to be a woman of African descent, communicated through the usage of nearly ebony paint for rendering her skin. She sells something, likely food, to a group of well dressed criollos, one a man in a red jacket and a Bourbon style tricornered hat. The Black woman stands in what appears to be tattered clothing, holding her wares on her head, while the creoles lounge, chat, and ponder their purchase. Even in such a tiny detail within the composition, it is clear that the artist intended to display racial difference and social hierarchies. The vision projected of the Alameda is one of a society designed to privilege those Spaniards in power.

Four figures (detail), attributed to Nicolás Enríquez, View of the Alameda Park and the Convent of Corpus Christi, c. 1724, oil on canvas, 206 x 146 cm (Palacio Real de Madrid)

A more modern scene

Today the Alameda still stands in Mexico City. It is the oldest public park in the Americas and continues to be an important public space in the life of the city. A mural painted in 1947 by Mexican artist Diego Rivera shows a more modern reconstruction of the Alameda Central.

Central figures (detail), Diego Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park, 1947, fresco, 4.8 x 15 m (Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City)

Rivera’s mural is a surrealist reconstruction of Mexican history, drawing together figures from various epochs to gather once again in the storied Alameda Central. In the distance through the trees looms one of the park’s famous fountains, grounding the setting for the scene. Through portraying the various strata of Mexican society and history, Rivera highlights the role of the Alameda Central as a civic space in the defining of a new, modern nation in the wake of the Mexican Revolution.