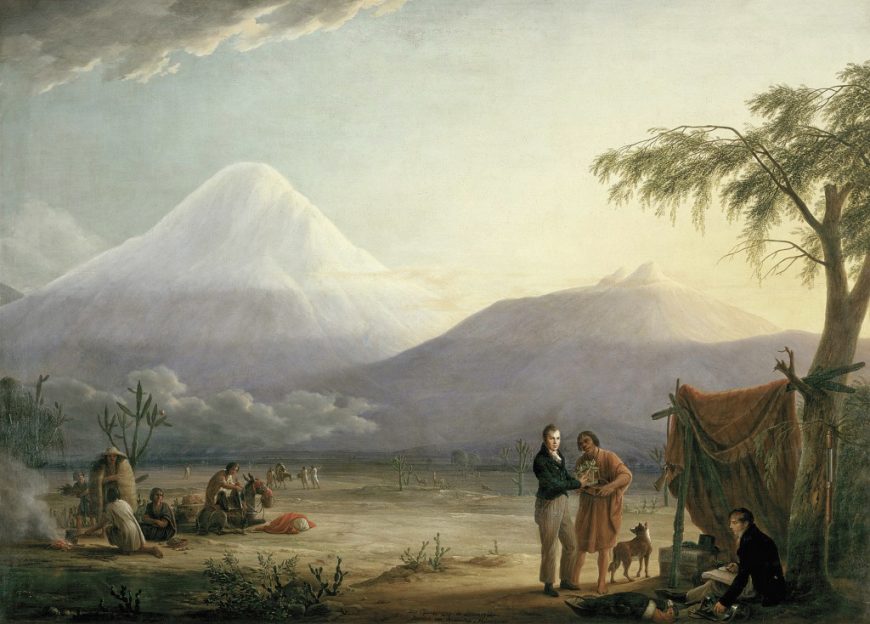

Friedrich Georg Weitsch, Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland at the Foot of the Chimborazo, 1806, oil on canvas, 163 x 226 cm (Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz)

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a growth in the inland exploration of Latin America. The desire of travelers, mainly European scientists, artists, and writers, was not to settle new frontiers. Many of these regions were colonized, or, in some cases, had even become independent from European imperial powers. Rather, the goal of these explorers was to understand the area’s botany, topography, people, and traditions. The knowledge they acquired came mainly from first-hand experience, in keeping with the Enlightenment idea of empiricism, which valued the concrete and measurable.

Disseminating knowledge

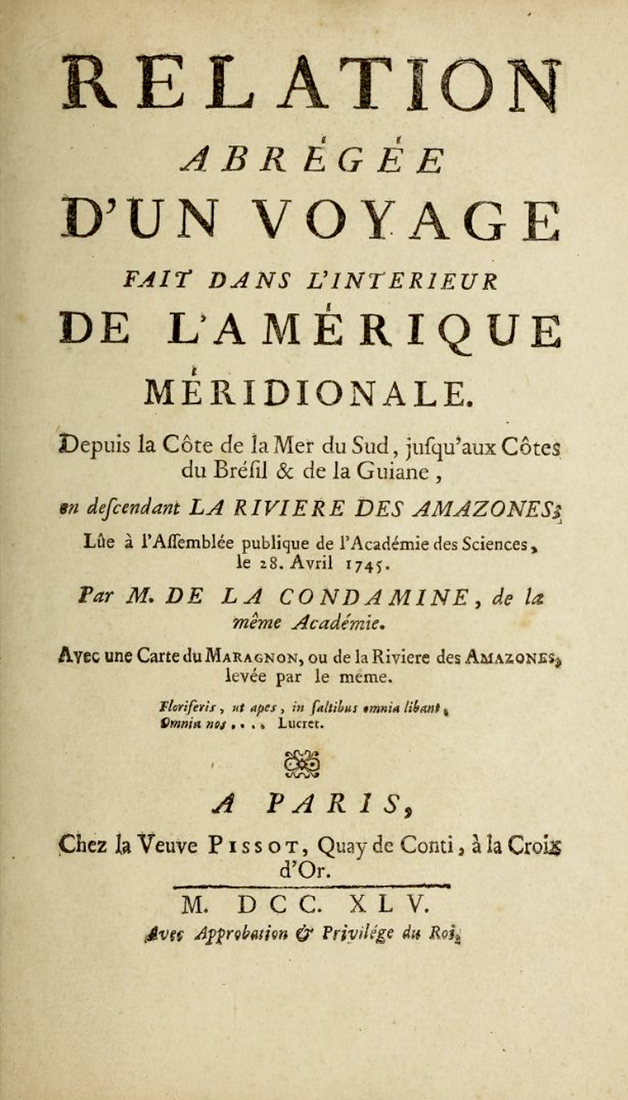

Charles Marie de la Condamine, An Abridged Account of a Journey Made in the Interior of South America (Relation abrégée d’un voyage fait dans l’interieur de l’Amerique méridionale), 1745

The distribution of these observations through various media (including books, prints, photographs, and watercolors) had a significant effect on how Latin America was conceptualized both locally and internationally. Travel books, in particular, catered to a foreign readership that could only dream of visiting far away places. For example, in the early eighteenth century, French naturalists, geographers, and engineers on the La Condamine Expedition explored the northern parts of South America—particularly Ecuador—with the goal of measuring the arc of the equatorial meridian. La Condamine’s publications in Europe helped spur interest in exploration.

The Spanish priest and botanist José Celestino Mutis was also one of the earliest researchers to contribute to the scientific documentation of Latin America, in this case through the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada, which began in 1783. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Mutis traveled extensively, documenting with extreme accuracy the flora of Colombia, among them the Mutisia Clematis, commonly known as clematis and named after the explorer himself. Botanical watercolors of these finds were valued first and foremost for their scientific accuracy, but their elaborate composition and vibrant use of color also demonstrate a concern for artistic technique and aesthetics.

Salvador Rizo, Mutisia Clematis, watercolor from José Celestino Mutis y Bossio, Flora de la Real Expedición Botanica del Nueva Reyno de Granada

The Humboldt expedition

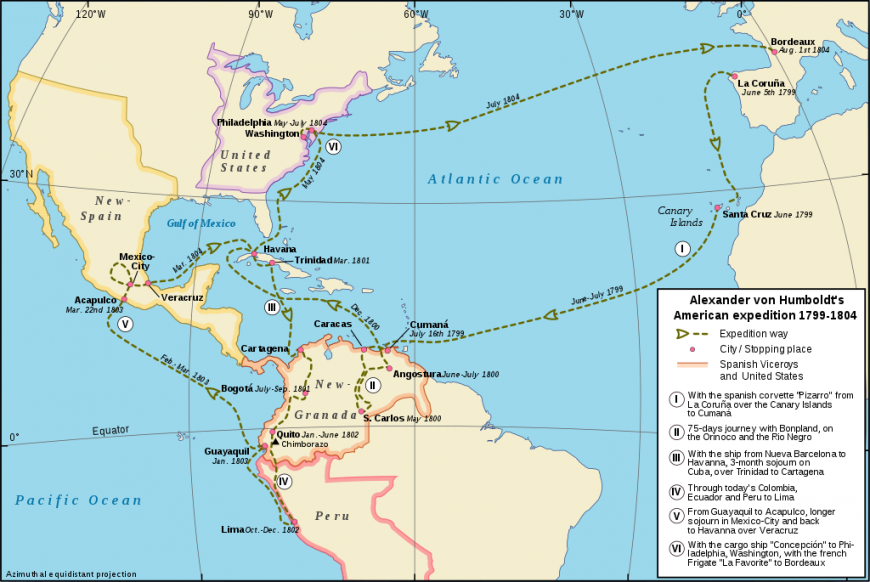

The most prominent explorer of Latin America during this time was the Prussian Alexander von Humboldt, who, together with French botanist Aimé Bonpland, surveyed the region from 1799 to 1804. Humboldt and Bonpland traveled more than 6,000 miles, through Venezuela, down the Orinoco River, through the Amazonian jungle, up towards Cuba, then back down to Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, traversing the Andes, sailing the Pacific Ocean northward toward Mexico, then back to Cuba, and finally to France, with a stop in New York. From this exhaustive voyage emerged some of the most detailed maps of the area, as well as documentation of multiple new species of flora and fauna.

Map of Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland’s American expedition, 1799-1804 (source: Alexrk, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Equipped with a variety of scientific instruments including thermometers, compasses, telescopes, and microscopes, Humboldt’s aim was to scientifically document the unique topography of Latin America. But he also hoped to capture the emotional intensity of these mysterious territories: in his writings, words such as a “grandeur” and “marvel” appear alongside scientific measurements, demonstrating the extent to which Humboldt was both a scientist and a romantic.

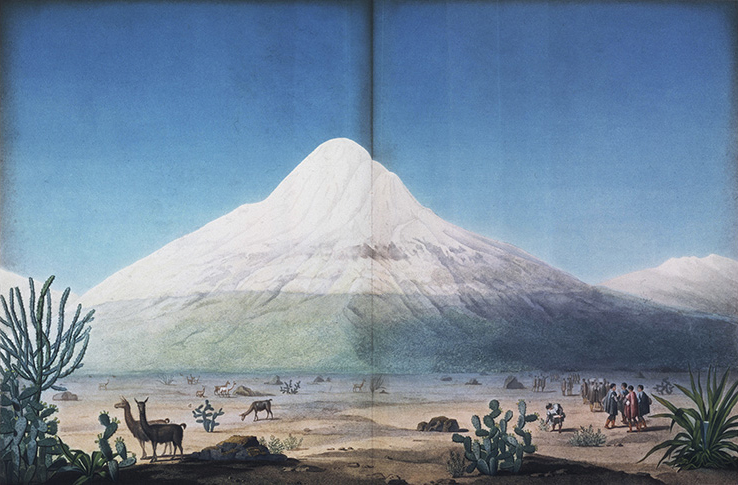

Humboldt’s and Bonpland’s findings appeared in various publications, one of which was Views of the Mountain Ranges and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of America (Vues des Cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique) (1810-1813), featuring 69 engravings. The centerpiece of the publication, Chimborazo Seen from the Tapia Plateau, Ecuador (below), occupies the entirety of two pages. This landscape captures the geological and environmental diversity of the region—including the immensity of the volcano (the highest in Ecuador), the recognizable plants on site, and the variations in the terrain (from an arid climate in the foreground to a snowy peak in the background).

Alexander von Humboldt, Chimborazo Seen from the Tapia Plateau, Ecuador, hand-colored engraving, in Vues des Cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique, 1810

These engravings were composite views, meaning that they were based on various drawings of different sites. This reflects the general trend of the time: to present images of nature that were grounded in research, yet expressed visually in ways that were picturesque—a word that is usually understood as meaning “quaint” or “charming,” but which in this case has a broader meaning, referring to views of nature that were enhanced versions of reality. Humboldt’s journey and writings sparked a strong interest in Latin America, prompting explorers, artists, and scientists to travel there, Including the American painter Frederic Edwin Church, Italian geographer Agustin Codazzi, and British scientist Charles Darwin.

Re-conquest through science

Though they brought much new knowledge to light, the activities of these explorers in many ways represented a re-conquest of Latin America, an inevitable result of the fact that the mapping, representation, and documentation of the region and its people was largely pursued by Europeans rather than locals. Such expeditions by outsiders contributed to the idea that Europeans were the sole “creators” of scientific knowledge.

Even if some Latin Americans did pursue such projects, their views of the territory were shaped in part by European modes of thought and representation: the perspective of the outsider looking in. And despite the existence and growth of scientific interest among locals, explorers, for their part, still preferred to romanticize Latin America “as a primal world of nature, an unclaimed and timeless space occupied by plants and creatures (some of them human), but not organized by societies and economies; a world whose only history was the one about to begin.” [1]

- Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, (New York: Routledge, 1992), p. 126

Additional resources:

Empiricism and the Enlightenment from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Frederic Edwin Church on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History