Edo period: artisans, merchants, and a flourishing urban culture

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory and territorial unification paved the way to a powerful new government. The Tokugawa shogunate would rule for over 250 years—a period of relative peace and increased prosperity. A vibrant urban culture developed in the city of Edo (today’s Tokyo) as well as in Kyoto and elsewhere. Artisans and merchants became important producers and consumers of new forms of visual and material culture. Often referred to as Japan’s “early modern” era, the long-lived Edo period is divided in multiple sub-periods, the first of which are the Kan’ei and Genroku eras, spanning the period from the 1620s to the early 1700s.

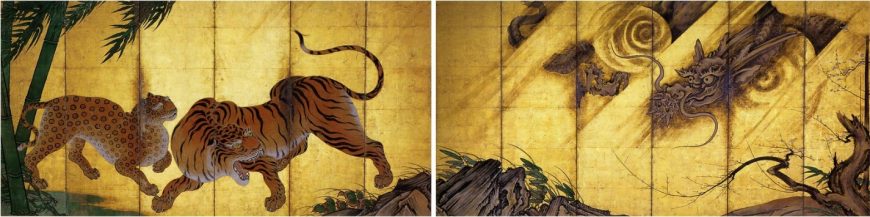

Kanō Sanraku, Dragon and Tiger, early Edo period, 17th century, pair of folding screens, color and gold on paper, 178 x 357 cm each (Myoshinji temple, Kyoto, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Kanō Tan’yū, Landscape in Moonlight, after 1662, one of three hanging scrolls, ink on silk, 100.6 x 42.5 cm. The signature mentions the painter’s Hōin title, “Seal of the Buddhist Law.” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

During the Kan’ei era, the Kanō school of painting, founded in the Muromachi period, flourished under the leadership of three of its most characteristic painters: Kanō Tan’yū, Kanō Sanraku, and Kanō Sansetsu. Their styles both emulated and departed from the formidable painting of Kanō Eitoku (discussed in the Momoyama-period section). Tan’yū was Eitoku’s grandson, Sanraku was his adopted son, and Sansetsu was Sanraku’s son-in-law (whom Sanraku eventually adopted as heir).

Their respective styles shared a creative tension between two diverging artistic directions: on the one hand, they were deeply influenced by the boldly expressive and monumental painting style of Eitoku; on the other hand, they adopted a less dramatic and subtly elegant manner, including a return to Chinese models and the earlier style of the Kanō school.

Tan’yū, in particular, spearheaded this conservative turn. His move to Edo as the painter of the Tokugawa shōgun marked a break with the Kyoto-based Kanō painters (including Sanraku and Sansetsu), one that was reflected in contemporaneous treatises that opined on issues of hierarchy and legitimacy within the school.

A versatile artist steeped in the Chinese tradition, Tan’yū was a connoisseur and collector of Chinese paintings. Drawing on his erudite visual vocabulary, Tan’yū painted both poetic landscapes in monochrome ink, typically evocative of classical subjects, and polychrome paintings in the Japanese style, accommodating large-scale commissions for palatial settings. In appreciation of his work, he was awarded, at age 61, the honorific title Hōin (“Seal of the Buddhist Law”).

Dish depicting lady with parasol, c. 1734–37, Hizen ware, Imari, design attributed to the Dutch Cornelis Pronk, porcelain with cobalt blue under clear glaze, 26.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Kan’ei and Genroku eras witnessed major developments in another medium, namely porcelain. The pioneers of Japanese porcelain were Korean potters brought to Japan after Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s incursions into Korea during the Momoyama period. These potters settled in Kyushu and paved the way for one of the world’s most innovative and prolific porcelain centers. Arita, Imari, Kakiemon are now household names, in part because of the 17th-century export of such wares from Northern Kyushu via the Dutch East India Company. This international trade company had contributed significantly to the global appeal of Chinese porcelain, particularly the blue-and-white variety. Despite the Tokugawa’s policy of self-isolation, the exception of allowing some Chinese and Dutch agents to continue international trade, combined with the political turmoil in China caused by the downfall of the Ming dynasty, created the optimal context for the Dutch to replace Chinese blue-and-white porcelain with Japanese porcelain in global trade. Japanese export ware, often referred to as Imari ware, emulated Chinese blue-and-white porcelain and reflected the Western tastes to which it catered.

Plate depicting autumn grasses and lozenge-shaped mist, Nabeshima ware, porcelain with underglaze blue and celadon glaze, 20.32 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Among the different porcelain kilns of northern Kyushu, Nabeshima ware was not for export but produced exclusively for the domestic market. The lord of Nabeshima, who had brought the Korean potters to his domain, embraced the local production that developed in the 17th century and patronized a special kiln whose porcelain he offered as strategic gifts to the shogun and other feudal lords. With its production processes kept secret, Nabeshima porcelain is distinguishable by its exquisite surfaces, adorned with delicate motifs drawn not from Chinese or European sources, but from the traditional Japanese visual repertory.

With its smooth surfaces and well-defined shapes, porcelain was markedly different from the stoneware produced in other ceramic centers of Japan, like the Oribe ware for tea rituals (described in the section on the Momoyama period). During the Edo period, the tea ceremony—both chanoyu and sencha, a different type of ritual for the preparation and enjoyment of steeped leaf tea—continued to flourish. Sencha, in particular, was integral to the literati culture. Japanese literati or bunjin modeled themselves on Chinese scholar-philosophers who were well-versed in painting, calligraphy, and writing poetry. As scholars with artistic pursuits, bunjin were not professional painters, but used painting—especially spontaneous renderings of landscapes, poems, and Chinese and Japanese traditional motifs in ink wash—as ways of expressing the inner energy of cultivated spirits that sought to achieve excellence by removing themselves from society and even defying societal norms. This model of reclusion was particularly embraced in periods of political unrest, which was definitely the case in Japan at the end of the 16th century during the turmoil that characterized Momoyama, the 40-year span that led to the Edo period. Gradually, literati practices developed a core tension between the rebellious and the highly individualistic, on the one hand, and the ritualistic and the normative, on the other, as traditions and lineages began to became more rigid over time.

Ike no Taiga and Yosa Buson, Ten Conveniences and Ten Pleasures, 1771, paired albums, color on paper, 17.7 x 17.7 cm (in the collection of the late Kawabata Yasunari, Kawabata Foundation, Kanagawa prefecture, image adapted from: Web Japan)

Bunjinga, literally translatable as “literati painting,” refers to painting practiced by these learned men. Literati painting often brought together references to both classical Chinese themes and local and contemporaneous literary sources, especially poems, often written by the painters themselves. The 18th-century haikai-no-renga poet Yosa Buson was also an accomplished painter and, in the collaborative spirit of haikai-no-renga, co-authored, with Ike no Taiga, a pair of albums on the Chinese theme of the “ten conveniences” and “ten pleasures” of life, combining idealized depictions of nature (mostly by Buson) with anecdotal renditions of human activities (mostly by Taiga). The collaboration between Buson and Taiga was both collegial and competitive, calling to mind the centuries-old Japanese tradition of poetry and picture contests that showcased talent and skill.

Maruyama Ōkyo, Pine Trees in Snow, between 1781 and 1789, left screen of a pair of folding screens, ink, color, and gold on paper (Mitsui Memorial Museum, image: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

A foil to Buson’s and Taiga’s approach to painting was the renewed search for realism of painter Maruyama Okyo. His naturalistic rendition of birds and animals, human figures, and landscapes contrasted with the literati mode by focusing on a rational regimen of visual representation, grounded in observation of the natural world. Trained in the European techniques of shading and one-point perspective, Okyo nonetheless created a synthesis of western-inspired naturalism and traditional Japanese techniques, styles, and subject matter. Okyo’s mode of painting was transmitted via the Maruyama-Shijō school, that Okyo first established as the Maruyama school. It was continued by Matsumura Goshun (whose studio was on the Shijō street in Kyoto), a painter who first studied with Buson and then turned to Okyo. These two closely related schools have been referred to as one entity since the late Edo period, when the distinctions between the two had faded. One of the most notable painters in the lineage of Goshun was Shibata Zeshin, a disciple of one of Goshun’s students, and an innovative painter and lacquer artist.

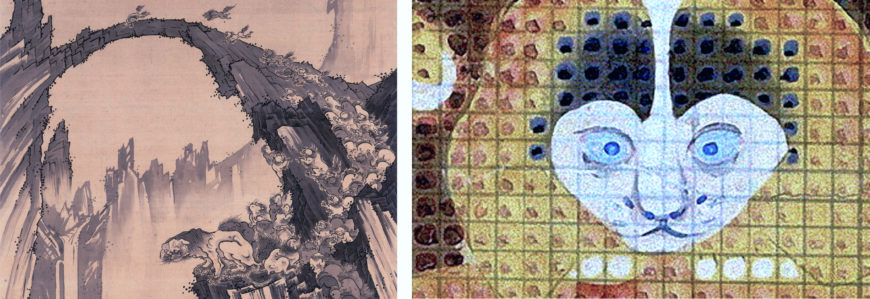

Left: Soga Shōhaku, Lions at the Stone Bridge of Mount Tiantai, 1779, hanging scroll, ink on silk, 114 × 50.8 cm, detail (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, full size image available here). Right: Itō Jakuchū, Birds, Animals, and Flowering Plants in Imaginary Scene, 18th century, pair of six-panel folding screens, ink and colors on paper, 137.5 × W355.6 cm, detail (Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, full size image available here)

Painters working outside established schools like the Tosa and the Kanō diverged from established modes of painting to varying degrees. Those whose styles were particularly unconventional have been recently re-evaluated as forming a “lineage of eccentrics” by Japanese art historian Tsuji Nobuo. Included in this “lineage” are Iwasa Matabei, Kano Sansetsu, Ito Jakuchu, Soga Shohaku, Nagasawa Rosetsu and Utagawa Kuniyoshi—each of whom had individual trajectories in their respective processes of maturing as visual artists. What they shared was a highly personal approach to painting, often characterized by unusual techniques and atypical subject matter. In Lions at the Stone Bridge at Mt. Tiantai, Soga Shōhaku chose a rarely depicted Buddhist theme and imagined it in novel ways, adding a whimsical dimension to it. In Birds, Animals, and Flowering Plants in Imaginary Scene, Itō Jakuchū painstakingly painted no fewer than 43,000 colored squares to create a fantastical, mosaic-like composition.

During the Edo period, a bustling urban culture developed. Merchants, craftsmen, and entertainers helped shape cultural and artistic tastes through their products and programs. Collaborative linked-verse parties and new forms of entertainment like kabuki theater became staples of the urban lifestyle. Tourism, too, gained in popularity as travelers went on pilgrimages to shrines, temples, and famous sites (meisho 名所), often associated with classical poems and traditional tales. All these cultural practices were mirrored in the popular paintings and prints known collectively as ukiyo-e 浮世絵. Literally “pictures of the floating world,” ukiyo-e can be best defined as genre painting for and about “common people” (shōmin 庶民)—members of the middle class of Edo-period Japanese society.

Hishikawa Moronobu, Two Lovers, c. 1675–80, polychrome woodblock print, ink and color on paper, 22.9 x 33.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Trained in his family’s textile business, 17th-century painter Hishikawa Moronobu was the earliest of the ukiyo-e masters. He focused on images of beautiful women (bijin 美人) and worked both in painting and woodblock printing. His depiction of women and lovers in Edo’s pleasure quarters deeply influenced subsequent ukiyo-e painters and print designers, notably Miyagawa Chōshun. Initially educated in the Tosa school, Chōshun signed his works by adding “yamato-e” to his name—a practice indicating that in its early days, ukiyo-e was regarded as a successor to the yamato-e style.

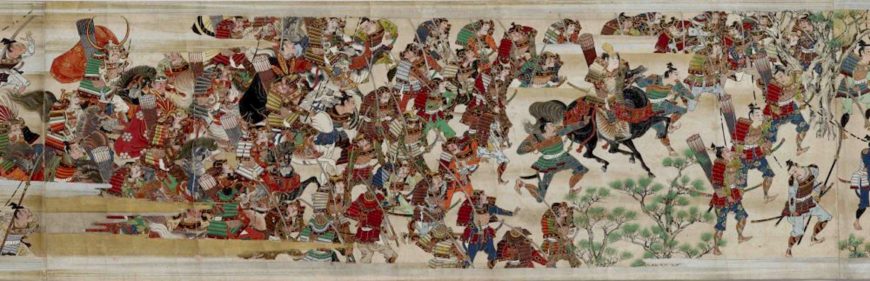

Iwasa Matabei, The Tale of Yamanaka Tokiwa, 17th century, handscroll, ink and color on paper, total length of over 70 meters, detail (Important Cultural Property, MOA Museum of Art, Atami, Shizuoka, Japan)

Contemporaneous with the ukiyo-e master Hishikawa Moronobu was the painter Iwasa Matabei, who, like Moronobu and his followers, saw himself as an heir to the yamato-e and Tosa-school traditions. Given his anecdotal painting style and his allegiance to Japanese subjects and painting techniques, Matabei is often regarded as a founding figure of ukiyo-e along with Moronobu. Matabei drew inspiration for his paintings from the classics of Japanese literature such as the Tale of Genji. However, in the spirit of ukiyo-e, his paintings are infused with a sense of everyday life and personal experience. The highly personal dimension of his art made others think of Matabei as one of the “eccentrics” (used here in the sense previously explained in relation to Shōhaku and Jakuchū, and aligned with the definition of art historian Tsuji Nobuo). Whether Tosa, ukiyo-e, or eccentric, Matabei broke with tradition by focusing on contemporaneous experiences and aspects of everyday life. Often, these themes were playfully intertwined with classical subject matter, resulting in a visual simile, which was at times parody, known as mitate. Realities of the present were superimposed over classical or mythic themes of the past. This practice ranges in Edo-period painting from an emphasis on the mundane and the anecdotal, as seen in Matabei’s compositions, to playful depictions of contemporaneous figures (such as beautiful women and kabuki actors) in the guise of legendary or historical figures such as poets and warriors, as seen later in the works of 18th- and 19th-century ukiyo-e artists like Andō (Utagawa) Hiroshige and Utagawa Kunisada.

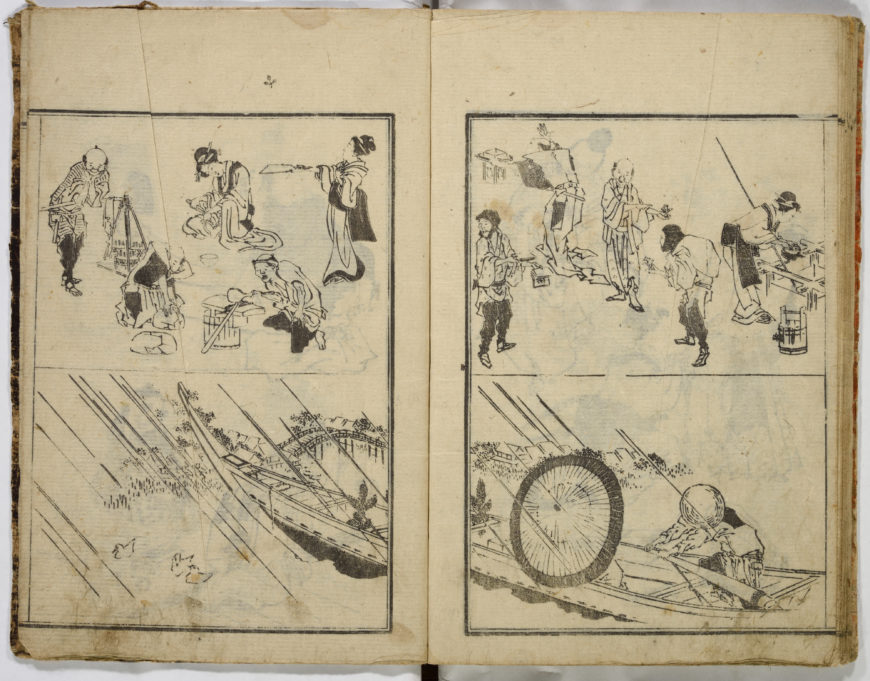

Hokusai, Random Sketches (Manga), 1834, eight volumes of woodblock printed books, ink and color on paper, 22.9 x 15.9 cm, two-page spread (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Hokusai’s Manga create a microcosm of Edo-period culture and have been a major source of inspiration for European artists in the 19th century.

Hokusai, Woodcutter, 1849, ink and color on silk, 113.6 × 39.6 cm (Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1904.182, Freer Gallery of Art)

Ukiyo-e images were made available in a variety of formats, from paintings and surimono to picture books (ehon 画本) and loose woodblock prints, often conceived in series (e.g. thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, seven episodes in the life of 9th-century poetess Ono no Komachi). One of the best known ukiyo-e masters and an emblem for Japanese art in the western world, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) not only designed woodblock print series and picture books, but also authored numerous paintings. Leading a frugal life and living in unkempt abodes, Hokusai was remarkably prolific over his long life, adopting various monikers and carefully dating his works by indicating how old he was when he painted them. Hokusai is deservedly famous for his exceptional draughtsmanship and exuberant imagination, coupled with a fine understanding of Japanese life and culture, both classical and contemporaneous. Like other Edo-period painters, he often inserted himself in his own work via quasi-self-portraits and reflections on impermanence and old age.

The Edo period saw an intensified circulation of visual vocabulary and aesthetic principles between mediums (paintings, ceramics, lacquerware, and textiles often shared the similar motifs) and crossing different registers of culture from design to popular culture to nostalgia for a romanticized pre-modern past. These intersections were further enabled by collaborations between artists of different specializations. One of the most consequential of these collaborations was that between the Kyoto-based, 17th-century painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu and calligrapher and ceramist Hon’ami Kōetsu.

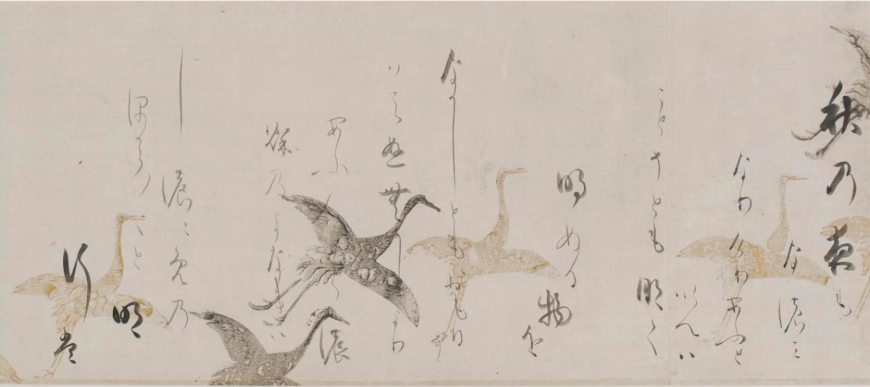

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (painting), Hon’ami Kōetsu (calligraphy), Poems from the Kokin wakashū, early 1600s, handscroll, ink, gold, silver, and mica on paper, 33 cm high, detail (Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1903.309, Freer Gallery of Art)

Hon’ami Kōetsu 本阿弥光悦, Tea bowl named Mino-game (“long-tailed tortoise”), earthenware with black Raku glaze, 8.7 x 12.5 x 12.5 cm (Freer Gallery of Art)

Their combined practice entailed an elegant aesthetic emphasizing traditional cultural references shared across painting, poetry, calligraphy, lacquer, ceramics, and tea ritual.

Along with potter Nonomura Ninsei, Kōetsu was among the first to sign their pottery in Japan. He would shape his tea bowls, then send them to the Raku-ware workshop to have the bowls glazed and fired. Kōetsu worked across multiple media and his collaborations with painters and potters contributed to a more unified visual culture. As is the case with Japanese art across the ages, lineages played a vital role in the survival and transformation of Sōtatsu’s and Kōetsu’s aesthetic programs.

Ogata Kenzan’s Narutaki workshop (1699-1712), Incense container with imagery from Tales of Ise, stoneware, underglaze cobalt and overglaze enamels, 2.5 x 10 x 7.3 cm (Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1907.84a-b, Freer Gallery of Art)

The intertwined styles of these two 17th-century artists were emulated and consolidated by the early-18th-century artists Ogata Kōrin and his brother Ogata Kenzan, who became school leaders in their own right. A familial relationship doubled this stylistic genealogy: Kōrin and Kenzan’s great-grandmother was an elder sister of Kōetsu. And the two brothers collaborated on occasion. Kōrin specialized in painting, while Kenzan became one of the most influential names in Kyoto-area ceramics. Later generations of potters emulated and even copied Kenzan’s style, while Kōrin gave his name to a new school, Rinpa (“Rin 琳” from “Kōrin 光琳” + “pa/ ha 派”, meaning “school”), that traced its aesthetic origins to Kōrin’s and Kenzan’s models, namely Sōtatsu and Kōetsu. Rinpa artists’ refined and ingenious designs were based on traditional themes and motifs, and rendered in gold, silver, and bold colors. They worked across mediums and genres ranging from painting to lacquer and from episodes in the Tale of Genji to depictions of the four seasons.

Left: Ogata Kōrin, Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges), after 1709, one of a pair of folding screens, ink, color, and gold on paper, 163.7 x 352.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). The depicted motifs evoke the classical Japanese text, the Tales of Ise. Right: Sakai Hōitsu, Summer and Autumn Flowers, right screen of a pair of screens, 164.5 x 181.8 cm (Tokyo National Museum). Hōitsu was a Rinpa artist who revived Kōrin’s style in the late 18th and early 19th century.

Additional resources

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Nobuo Tsuji, translated by Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, History of Art in Japan (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2019)

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)