From the Meiji restoration (1868) to the first year of Reiwa (2019):

modern and contemporary art, part I

Meiji period (1868-1912)

Nanri Kajū II, pair of vases, c. 1875, porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze enameling and gilding, 75.7 cm high (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

1868 was a watershed year for Japan. After over two centuries of shogunal rule, practical political power was restored to the emperor (Meiji). 15 years earlier, the American commodore Matthew Perry led a military and diplomatic expedition to Japan, opening the country to foreign trade and thereby ending the Tokugawa-imposed self-isolation policy. The effects of this forcible “opening” were manifold and deeply affected Japan’s social and cultural fabric. Japan began to participate in World’s Fairs, curating displays of samples of Japanese cultural tradition designed for the outside world to see, and often taking the form of new porcelain vases that impressed through their monumental scale, technical excellence, and intricate decoration.

In the realm of painting, the 1870s saw a new mode of image-making that embraced western styles and techniques, known in Japanese as yōga 洋画 (“Western-style painting.”) A pioneering yōga artist, Takahashi Yuichi assisted Antonio Fontanesi, the “foreign advisor” appointed by the Meiji government to teach oil painting at the newly established Technical Fine Arts School in Tokyo. Further developed by painters like Kuroda Seiki, who studied extensively in Paris and worked in Japan into the 1920s, yōga largely embraced contemporaneous styles of French painting, from the Barbizon School to Impressionism, and their connected practices, from painting from nature to favoring subject matter drawn from the here and now.

Kuroda Seiki, Lakeside, 1897, oil on canvas, 69 x 84 cm (Important Cultural Property, Tokyo National Museum)

As a foil to yōga, other Japanese visual artists developed a parallel mode of painting, known as nihonga 日本画 (literally, “Japanese painting.”) Rejecting a straightforward adoption of techniques and styles from Euro-American pictorial traditions, nihonga was not a direct continuation of the earlier yamato-e either. Instead, nihonga broadened the traditional themes of yamato-e, created new blends of Japanese stylistic traditions like Kanō and Rinpa, and even incorporated western modes of pictorial realism in its reinvention of Japanese painting.

Yokoyama Taikan, Kutsugen (The Legendary Chinese Poet Qu Yuan), 1898, hanging scroll, colors on silk, 132.7 × 289.7 cm (Itsukushima shrine, Hiroshima, image: public domain). This painting is thought to express the painter’s loyalty to his teacher—the influential, if controversial, thinker Okakura Kakuzō. Resentful against oppressive authority, this classical Chinese poet becomes here a surrogate for Okakura, who had just resigned from the new Tokyo Fine Arts School because of internal frictions.

Two artists who significantly shaped nihonga were Kanō Hōgai and Yokoyama Taikan. Remembered as the last great master of the Kanō school, Kanō Hōgai helped pioneer nihonga alongside fellow painter Hashimoto Gahō, himself trained in the Kanō style, and Ernest Fenollosa, an American poet and art critic who assumed important cultural positions in Meiji-period Japan, as professor of philosophy and curator at the newly established Tokyo Imperial University and Imperial Museum, respectively. Modeled on European and American universities and museums, such institutions altered the old structures of the Japanese cultural field. New words became necessary in the Japanese language to translate and use foreign concepts such as “fine art” or “artist.” Thinkers like Fenollosa or Okakura Kakuzō—a sort of cultural ambassador who explained, through his subjective lens, Japanese culture to elite American audiences—affected both the production and the reception of what constituted “Japanese art” in the Meiji period. Born out of Okakura’s teachings on traditional Japanese culture was the quintessentially nihonga style of painter Yokoyama Taikan. His paintings combine canonically Japanese and western-inspired elements with unconventional techniques and high symbolic content.

Otagaki Rengetsu, Sencha cups with poems, 19th century, white stoneware, 4.13 × 6.51 × 6.35 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

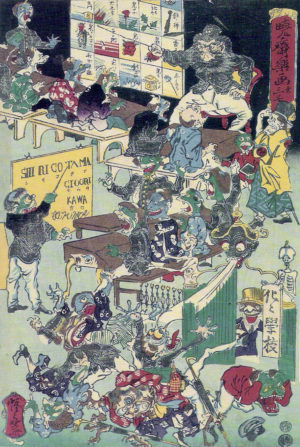

Kawanabe Kyosai, School for Demons and Ghosts, 1870s, woodblock print (image: public domain). Here, Kyosai imagines demons and other fantastical creatures learning new vocabulary—a commentary on the newly instituted Meiji-period compulsory education.

Yet other modes of painting co-existed with the strong yōga and nihonga trends. Somewhat aligned with Euro-American post-Impressionism, the artist Tomioka Tessai created his individualistic style through an inventive blend of influences, largely drawn from classical Japanese and Chinese sources. Tessai’s mentor, friend, and frequent collaborator was Otagaki Rengetsu, an artist and Buddhist nun who expressed her unique style via pottery, poetry, painting, and calligraphy. Another idiosyncratic artist of the period was Kawanabe Kyōsai, who “translated” his experience of the drastic changes that Japan underwent in the 19th century into caricatures within an exuberantly inventive pictorial realm. Through such artists, the Meiji period furthered the spirit of centuries of poetic and playful interplay among mediums and styles in Japanese arts.

Spurred by new ideas about the nation-state and by the reconfiguration of society in the modern era, Japanese urban life was transformed in the Meiji period. With this transformation came different modes of living and new architectural styles for buildings that housed newly established public institutions and for family homes, influenced by western-centric concepts of domesticity. Modeled on western architecture, buildings were built with brick and stone instead of the traditional wood. Merging international and indigenous elements, an eclectic architectural style emerged, championed by architects like Itō Chūta, who also helped establish cultural preservation laws for ancient structures such as temples and shrines.

Itō Chūta, Main Gate, Tokyo Imperial University (currently the University of Tokyo), built 1912. This gate is emblematic of Meiji-period architecture as it combines Euro-American elements—note the use of steel and granite—and Japanese elements—note the traditional gate style, known as kabuki-mon (photo: XIIIfromTOKYO, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Taishō period (1912-1926)

The Taishō period continued the process of adoption and transformation of foreign models. During this period Japan participated in World War I and continued its colonial rule of Korea and Taiwan, occupations dating from the Meiji period. In the cultural field, the eclectic style that had emerged in architecture continued to flourish, with structures emulating modernist trends like Bauhaus and Art Deco. The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, a natural disaster of catastrophic proportions, not only destroyed buildings and other cultural properties, but marked a shift in Japanese society from the optimism of the Taishō period to the radicalized nationalism of subsequent decades.

Yasuda Auditorium, architect: Uchida Yoshikazu, patron: Yasuda Zenjiro, built 1925, renovated after 1968 (image: Kakidai CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Yasuda auditorium, built in 1925 on the campus of the University of Tokyo, epitomizes the brief but consequential Taishō period. Designed in an Art Deco mode and reminiscent of the campus of the University of Cambridge, the Yasuda auditorium was sponsored by one of the founders of the Yasuda zaibatsu. It was intended as a temporary resting facility for the emperor when he visited the university. As such, the auditorium embodied the socio-cultural influence of the new financial magnates, the rising nationalism concentrated in the persona of the emperor, the adoption of the European Art-Deco architectural style, and the affirmation of the university as a modern research center.

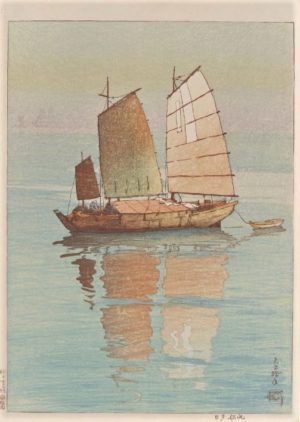

Yoshida Hiroshi, Sailing Boats: Evening Glow, 1921, shin hanga, woodblock print, ink and colors on paper (Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Robert O. Muller Collection)

Nihonga, or (modern) Japanese painting, continued to develop at the intersection of Japanese tradition, western techniques, and individual styles. The Nihonga painter Yokoyama Taikan resurrected the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Art Institute) after it had lapsed following the death of its leader, the controversial but influential thinker Okakura Kakuzō. Such developments ensured a continuation of Meiji-period discourses on the arts, entailing the adoption of western notions and terms and the formulation and crystallization of new concepts, all reflected in newly coined Japanese-language words.

An equivalent to Nihonga was the shin hanga phenomenon, namely the formation of new modes and styles of printmaking that simultaneously revitalized ukiyo-e (as defined in the section on Edo-period arts) and incorporated elements of modern design and western-inspired realism. While shin hanga largely preserved the multiple hands traditionally involved in the design and production of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, another mode of Japanese printmaking that emerged in the 1910s, known as sōsaku hanga, emphasized individual expression and featured a sole creator in charge of all aspects of the print’s production (from drawing to carving to printing). Sōsaku hanga resonated, and drew upon, contemporaneous thinkers and writers like Natsume Sōseki who advocated self-expression.

From the Meiji restoration (1868) to the first year of Reiwa (2019):

modern and contemporary art, part II

Shōwa period (1926-1989)

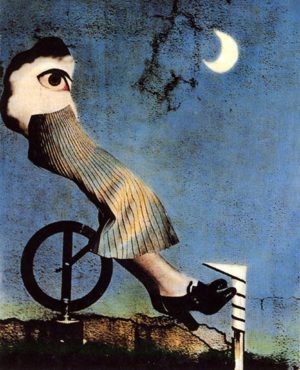

Hirai Teruschichi, Fantasies of the Moon, 1938, gelatin silver print, painted collage (© Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture, image: Tokyo Digital Museum)

The years leading to Japan’s involvement in World War II saw the rise of militarism, ultra-nationalism, and increasing imperialistic ambitions, fueled in part by Japan’s emulation of western colonialism. In the 1920s and 30s, Japanese poets, photographers, and painters who had studied abroad developed, in Japan, styles aligned with contemporaneous global art movements, combining elements of surrealism, absurdist Dada, and futurism. For example, the paintings of Fukuzawa Ichirō combined surrealist imagery with political commentary; Hirai Terushichi made use of color painting and photomontage to create photographic prints that blurred the boundary between reality and imagination.

Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Battle on the Bank of the Halha, 1941, oil on canvas (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

Such artists were silenced in 1941 by the Japanese “thought police” that aimed to control any and all ideologies that seemed to pose a threat to the ideals and agenda of the Nazi-allied Empire of Japan. War-time painting depicting military men and battles came to be heavily criticized after the war for their political charge, but recent scholarship by Ikeda Asato suggests that seemingly apolitical paintings of the pre-war period, which romanticized subjects of “authentic” Japanese culture such as Mount Fuji or bijin (“beautiful women”), can also be understood as having supported the militaristic state ideology of the time.

Postwar Japan was a period of unprecedented change. From the end of the war in 1945 to 1952, Japan was occupied by the victorious Allied forces, led by American General Douglas MacArthur. From 1952 to the death of the Shōwa emperor (Hirohito) in 1989, Japan witnessed a successful U.S.-influenced economic redevelopment. In the cultural sphere, as early as 1954, the newly established Gutai art association promoted “concrete” or “embodied” artistic expressions, pushing abstraction to its limits and foreshadowing the performance and conceptual art of the 1960s and 70s.

Sekine Nobuo, Phase: Mother Earth, 1968, earth and cement, 220 x 270 cm (equally sized hole and cylinder) (Kobe Suma Rikyū Park Contemporary Sculpture Exhibition, 1968, image: Murai Osamu, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In those later decades, the exploration of materiality continued to preoccupy artists of the so-called mono-ha (literally “school of things”), including the Korean Lee Ufan. Mono-ha artists created works that tested the tension between natural and manmade materials and between their chosen materials and the environment in which they were placed. Mono-ha artists may have been influenced by the sociopolitical climate of distrust, protest, and counterculture that dominated the 60s and 70s. Referring to one of his most influential works, Phase: Mother Earth, consisting of a deep and wide hole in the ground and an equally sized cylinder of the excavated earth, the Mono-ha artist Sekine Nobuo affirmed:

“If you dig a hole in the earth and keep digging forever, (…) and if you go on to pull out all the earth, [the Earth] will be reversed into a negative version of itself.”Sekine Nobuo cited in Reconsidering Mono-ha, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2005, p. 74

The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923 and the ravages of war created successive scenes of destruction and contributed to a collective memory of ruins, used as evocative subject matter by Japanese painters and photographers to this day.

In the postwar period, reconstruction was not only political and economic, but also literal, in the urban and architectural sense. Modernism was adopted as the language of this reconstruction. The architect Tange Kenzo, who worked for Maekawa Kunio, one of Le Corbusier’s disciples, became one of the most consequential postwar modernists both as an architect and as an urban planner.

Kurokawa Kisho, the Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo, completed 1972, detail of exterior view of prefabricated units (image: City Lab)

Tange’s unrealized “Plan for Tokyo 1960” heavily influenced the Metabolist movement, which Tange himself supported. Emblematic of Metabolism is the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Shinbashi, Tokyo, whose capsule-like rooms are prefabricated units meant to be replaced once they wore out. The “capsules” were designed as integral to a megastructure of both permanent and impermanent parts, built in the spirit of organic growth.

Heisei period (1989-2019)

Corresponding to the reign of emperor Akihito, the Heisei (literally, “achieving peace”) was a period of peace, but one that nonetheless witnessed economic stagnation and natural disasters. In the cultural sphere, the Heisei period saw the establishment of new art museums and the adoption of new means of expression among Japanese artists, although always in dialogue with the recent or more distant past.

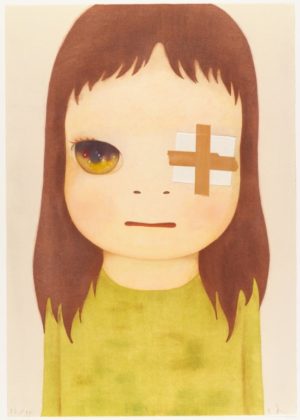

Yoshitomo Nara, Untitled (Eye Patch), 2012, woodcut with collage additions, 68.7 x 48.3 cm, Pace Editions, Inc. (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Manga and anime exploded in popularity and influence during this period, although both have deep histories. Manga refers generally to comics and its roots harken back to medieval narrative picture scrolls. Anime refers, of course, to animation, which goes back to the early 20th century and includes, in Japan, the controversial history of its use as a propaganda tool during World War II. In the 1990s, the anime industry grew via revivals and sequels of popular 1970s productions as well as via new genres.

Popular both domestically and internationally, anime and manga are closely related to the principle of kawaii, translated as “cute.” This culture of “cuteness” has often been understood as a form of escapism from the harsh realities of the postwar period and of a country often threatened by calamitous natural disasters. Artists like Yoshitomo Nara and Murakami Takashi use elements from manga and anime to explore the darker underside of kawaii.

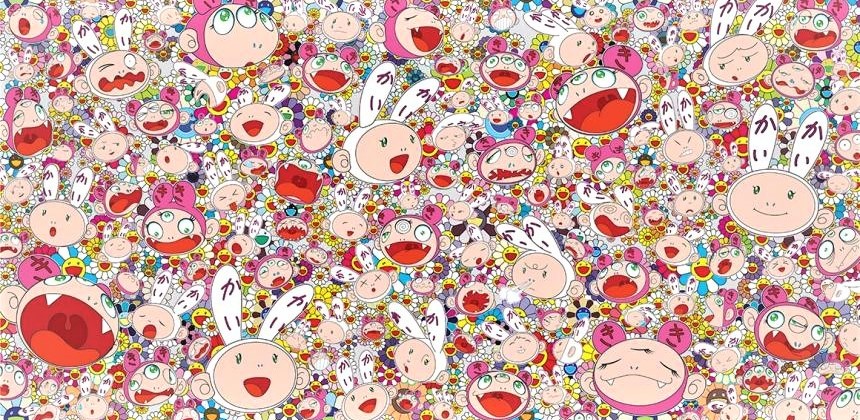

Artists like Murakami Takashi refer not only to the contemporaneous culture of manga and anime in their works, but also to older lineages and genealogies of Japanese art history. Murakami is a case in point with his personal and often provocative interpretations of Edo-period “eccentric” painters whose works nonetheless became integral to the canon of Japanese visual arts. Like Andy Warhol or more recently Jeff Koons, Murakami complements his works in painting, sculpture, and installation with merchandise and publications produced by his company, Kaikai Kiki.

Takashi Murakami, Lots, lots of Kaikai and Kiki, 2009, acrylic and platinum leaf on canvas on aluminum frame, 300 x 608 cm (private collection, © Takashi Murakami, Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.) In this painting, the seemingly inescapable accumulation of otherwise “cute” anime-like figures creates a disquieting realm, one that can serve as playful commentary both on the “flat” representation of traditional Japanese painting and on the overwhelming presence of commercial imagery.

Contemporary Japanese artists use a variety of mediums to express their vision or to focus on the perfection and re-invention of a medium. For example, Sugimoto Hiroshi has gained international acclaim for his contemplative photographs of seascapes as well as for his site-specific sculptural and architectural works. Mariko Mori epitomizes the multidisciplinary artist, exploring her sense of identity and developing her surreal imagery through photography, video, sculpture, installation, and performance. Distinct from artists like Sugimoto and Mori, many contemporary Japanese ceramists devote themselves exclusively to the materials and practices of ceramic art; and similar to artists like Murakami, they produce new works that both honor and challenge tradition.

Mariko Mori, Esoteric Cosmos (Pure Land), 1996-98, glass with photo interlayer, 305 x 610 x 2.2 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © Mariko Mori)

As of May 1st, 2019, when emperor Akihito’s son, Naruhito, ascended the throne, we entered a new era for Japan, namely the Reiwa (translatable to “beautiful harmony”). In Japan as elsewhere, the art of today continues to resonate with the past, while carving its own path forward.

Additional resources

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)