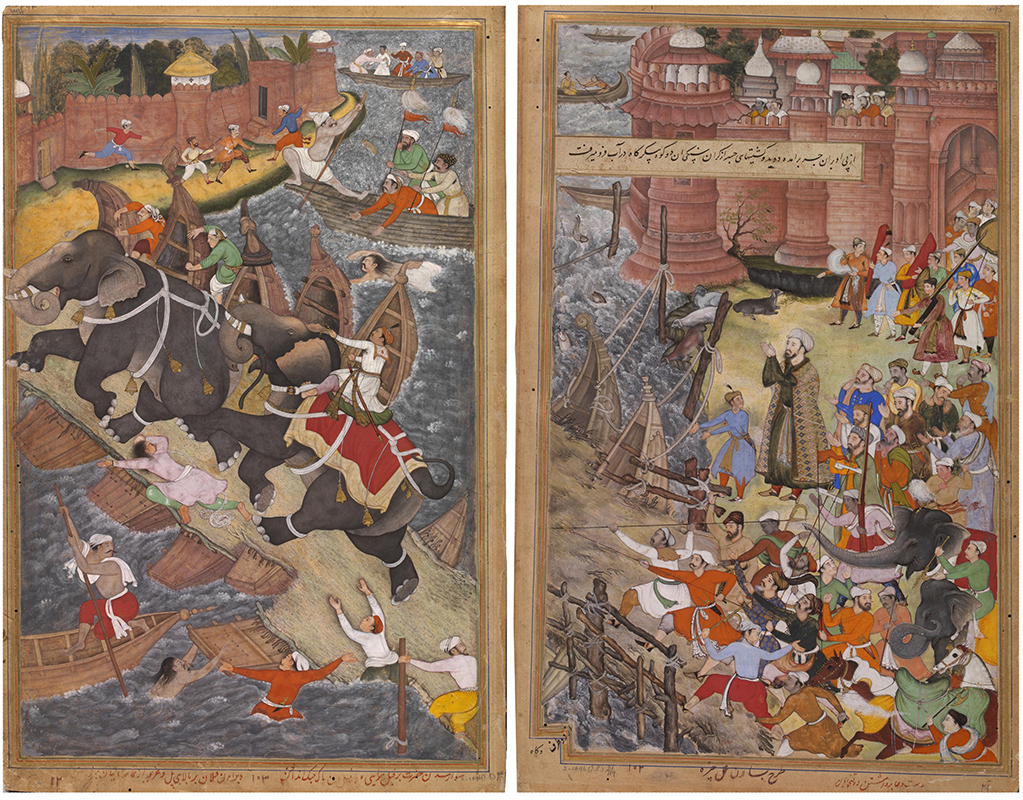

“Emperor Akbar on an elephant hunt,” Basawan and Chetar, illustrations from the Akbarnama, c. 1586–89, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, each page 33 x 30 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

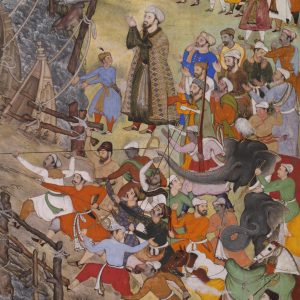

In these small, brilliantly-colored paintings from the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), a rampaging elephant crashes over a bridge of boats on the River Jumna, in front of the Agra Fort. He is so out of control that his tusks, trunk, and front leg burst through the edge of the frame (see image below). Several nearby men scramble to get out of the way, clinging to the edges of their boats or leaping into the water for safety. The accompanying right page shows a swirling mass of onlookers, each expressing distress and astonishment at the event unfolding before their eyes.

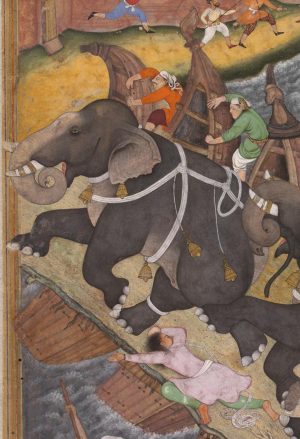

“Ran Bagha crossing the River Jumna” (detail), Basawan and Chetar, illustration from the Akbarnama, c. 1586–89, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 33 x 30 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

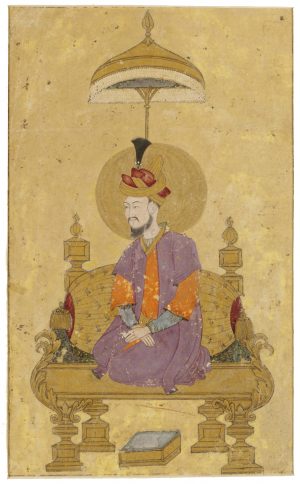

The scene is a royal elephant hunt where the Mughal emperor, Akbar, has mounted Hawa’i—an elephant known for its wild and uncontrollable disposition—to fight the equally fierce elephant Ran Bagha, who leads them on a wild chase across the river. The most prominent onlooker is the Prime Minister Ataga Khan, who holds his hands in prayer for a peaceful resolution to this chaotic scene. In the midst of the turmoil, we see Emperor Akbar, upright and unfazed, riding barefoot on the royal elephant—the very embodiment of majestic strength, courage, and faith in divine protection (below). These illustrations encapsulate, both symbolically and literally, the significant achievements of this remarkable man as told in the Akbarnama, the book he commissioned as the official chronicle of his reign.

Basawan and Chetar, “Akbar” (detail) from the Akbarnama, c. 1586–89, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 33 x 30 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Akbar the Great

Abū al-Fatḥ Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Akbar was the third emperor of a new dynasty, the Mughals, a Muslim empire established in India in the early sixteenth century by Babur, a descendent of Genghis Khan. (The name itself, Mughal, attests to this legacy, as it is the Persian and Arabic word for “Mongol”). Upon Babur’s death in 1530, the new empire was left to his 22-year-old son, Humayun, who quickly lost control of the majority of his domain as sultans fought to regain their land. In 1543 Humayun was forced to flee India and leave his young son Akbar in the care of his family at Kandahar.

Emperor Humayun, 18th century, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor on paper, 18.3 x 11.1 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

These events could have led to the end of both the fledgling empire and their lives, yet circumstances took a turn that had a profound impact on the destiny of the Mughals, and in particular that of Akbar. The Safavid Shah Tahmasp I welcomed Humayun to his court in Persia (present-day Iran), not as a fugitive, but as an equal, granting him protection and military support. Immersed for two years in the refinement and splendor of the arts and culture there, Humayun was exposed to an opulence and sophistication unlike anything he had ever seen in his father’s military encampments. As a result of his stay in Iran, the original language of the Mughals was abandoned in favor of Persian, monumental architectural forms were adopted and refined, and an imperial workshop of painters in the Persian miniature style was founded. Reunited with his son in 1545, Humayun eventually regained control of India before dying suddenly in 1556. When Akbar inherited the Mughal territories at 13 years old, he was surrounded by rivals on all sides: there was no stable government, no art the empire could call its own, and not much hope for a future. However, within less than 50 years, Akbar created all of these things and succeeded in bringing together the diverse peoples and cultures of India to form an unprecedented, cooperative whole. Akbar was instrumental in the formation of a powerful empire that lasted over 200 years.

“Emperor Akbar chasing Ran Bagha across the River Jumna,” Basawan and Chetar, illustration from the Akbarnama, c. 1586–89, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 33 x 30 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Across many cultures and time periods, a ruler’s control over the natural world is a defining symbol of noble power, and Mughal India was no exception. Akbar’s regal authority, military prowess, and personal courage are visibly celebrated in this painting through his complete control of an elephant—an animal with a long history in Indian culture as the embodiment of majesty, power, and dignity. Yet this illustration shows us Akbar’s great triumphs in more than just the subject matter: the innovations in the work’s artistic style are also reflective of the acute intelligence, voracious curiosity, and enthusiastic artistic sponsorship for which Akbar is remembered.

Mughal painting under Akbar the Great

Akbar was a champion of new styles in literature, architecture, music, and painting. Although his son Jahangir later chronicled that Akbar was illiterate, it is most likely that Akbar was dyslexic, which would have made it very difficult for him to read. Despite this personal challenge, at the time of his death in 1605 the imperial library contained 24,000 volumes, and the number of painters in the imperial workshop had expanded greatly. Much like his political policies, which encouraged tolerance, Akbar’s court included artists from all regions of India, creating a melting pot of techniques and styles. As a result, Mughal painting under Akbar the Great is known for its unique blend of indigenous Indian, Persian, and Western traditions.

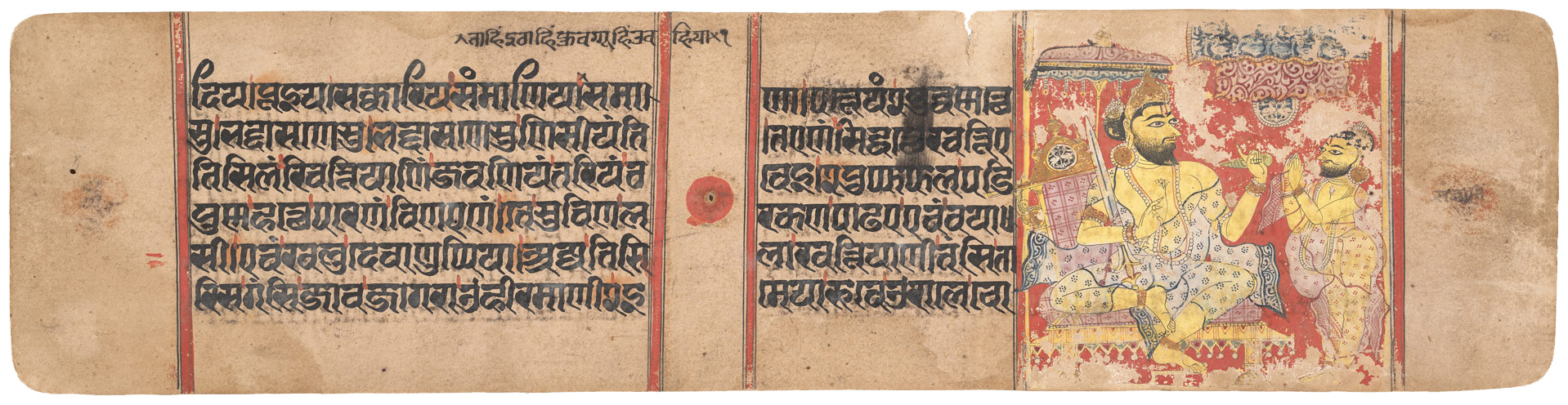

“King Siddhartha Listens to an Astrologer Forecast the Conception and Birth of His Son, the Jina Mahavira,” from a Kalpasutra manuscript, late 14th century, India, opaque watercolor on paper, 8.6 x 35.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This page from a Kalpasutra manuscript from the fourteenth century beautifully illustrates the basic qualities of the Indian tradition, with its use of bold primary colors and its horizontal format. The visual emphasis is on the text, which occupies roughly two-thirds of the page. Although the illustration (which shows King Siddhartha speaking to an astrologer who will foretell his son’s birth) takes up the smallest portion of the page, the size of the figure is very large in relation to the picture plane, with the king’s form filling up the space of the frame.

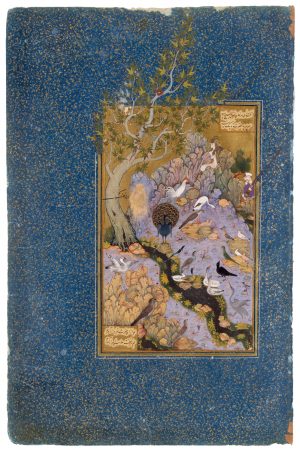

“The Concourse of the Birds,” from Habiballah of Sava, Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), c. 1600, Iran, ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 25.4 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In contrast, the Persian tradition (above) preferred a vertical format, with greater emphasis on landscape and decorative elements. In “The Concourse of the Birds,” an illustration of a mystical poem made around 1600, the color palette is much more subdued, with a preference for pastel colors like pinks, soft blues, and soft greens. The figures in the painting are relatively small, completely embedded within a scene that is rendered with painstaking detail. The subject matter of this type of manuscript—typically poetry or the pleasures of courtly life—was meant to illustrate the elegance and refinement of the ruler. How could it be possible to blend two such disparate artistic traditions?

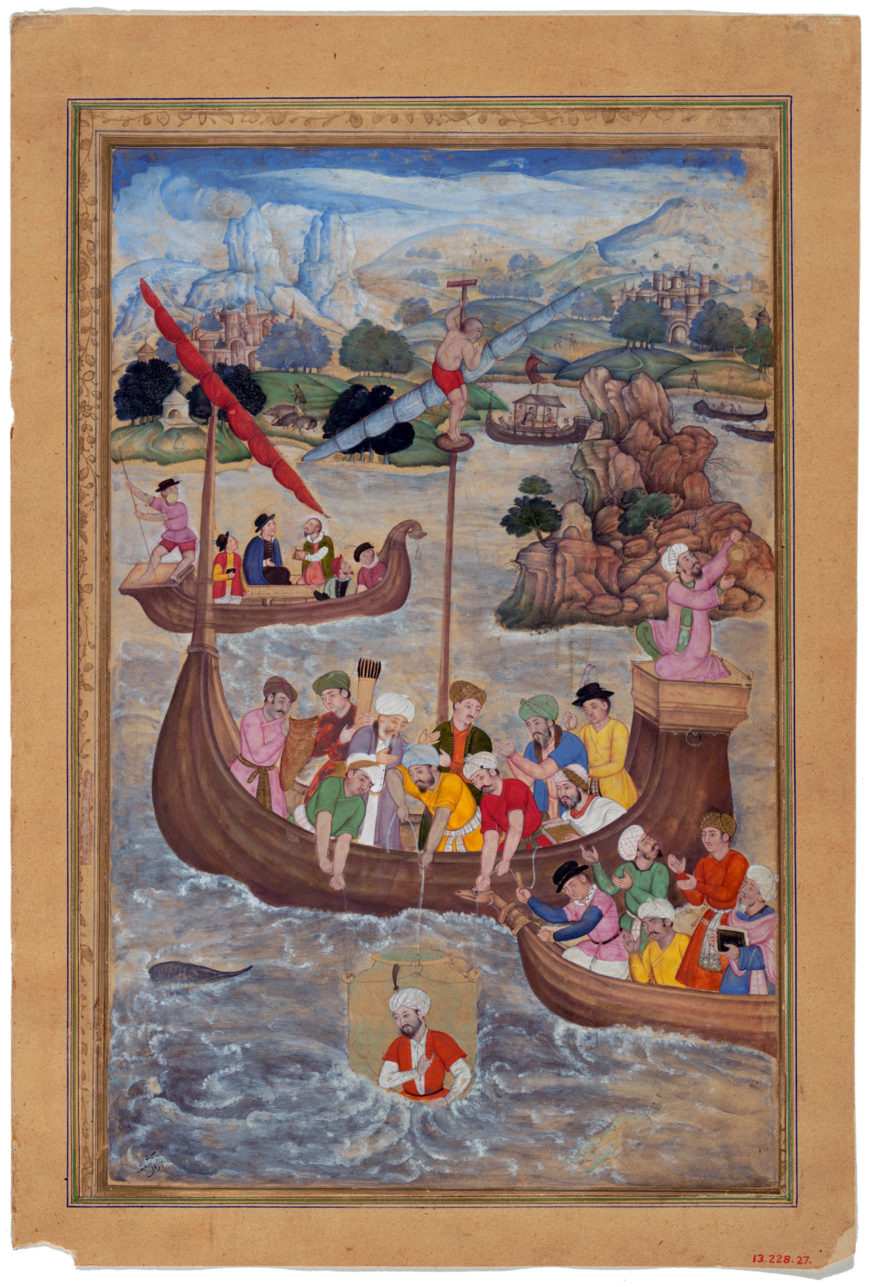

“Alexander is Lowered into the Sea”, folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi, 1597–98, India, ink, watercolor, and gold on paper, 9-3/8 x 6-1/4 inches (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

To further complicate matters, Western missionaries made contact with Akbar in the late sixteenth century, bringing with them European artworks and religious texts illustrated with engravings. Akbar and his expansive atelier of painters were intrigued by the illusion of depth achieved through linear perspective, as well as by novel visual attributes such as halos on religious figures. Some scholars have characterized these Western artistic traditions as the ultimate goal to which Akbar and his painters aspired; however, many Islamic artists instead integrated this new visual vocabulary into their own rich traditions. In “Alexander is Lowered into the Sea” (above), an illustration from a text of Indian poetry embellishing upon the military and spiritual adventures of the ancient Macedonian king, we see Alexander the Great, dressed in contemporary Mughal attire, seeking adventure and spiritual insight in the watery depths. Beyond its key figure, notice the other ways European ideas and techniques are included, such as the presence of European figures and the hazy blue hues of the rolling hillside at the top of the painting, indicating distance and spatial recession. And yet, many aspects of this work are distinctly Persian and Indian in style, such as the three-quarter views of their faces, the soft pastel, cloud-like rock formations, and the size of the figures in relation to the picture plane. Through the balance of seemingly contradictory styles, the artist has created an energetic scene of inspired originality.

“Ataga Khan and onlookers praying for a peaceful resolution” (detail), Basawan and Chetar, illustration from the Akbarnama, c. 1586–89, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 33 x 30 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The elephant hunt: a blend of styles

In creating the Akbarnama, the artists in Akbar’s atelier were equally proficient at blending elements from Indian, Persian, and Western traditions, while developing a distinct style of their own. In the illustration of the elephant hunt from the Akbarnama, they have retained the vertical format favored in Persian painting, as well as its traditionally intricate patterning of nature, seen in the rhythmic pulsing of the waves. In the right panel, the onlookers express fear and awe through the standardized Persian gesture of lightly pressing a finger to the lips. Yet many other figures are seen with their arms thrown overhead in distress, or with their bodies positioned off-balance, demonstrating the artists’ independence in choosing whether or not to utilize standard gestures.

The vibrant hues, on the other hand—especially the deep reds and yellows—call to mind the Indian tradition and its preference for saturated primary colors. The scale of the figures in relation to the picture plane is also much larger than in the Persian style, demonstrating a preference for the Indian tradition’s emphasis on the human form. Elements from Western artistic traditions are also present, most notably the indication of depth and distance achieved by rendering the boats and buildings as increasingly small as one looks to the top of the page.

Clearly, these artists enjoyed a remarkable degree of freedom to experiment and develop new artistic amalgams under Akbar’s patronage. Akbar’s court historian, Abu’l Fazl, noted the intense personal interest taken by Akbar in his workshop, where he personally commissioned specific subjects and conducted regular viewings of new work each week. In the illustrations of the elephant hunt, we can see his preference for depictions of heroic personal feats. From the sharp diagonal placement of the elephants upon their precarious bridge of boats, to the depiction of the thrilling story at its climax, this scene is full of vigor, action and excitement.

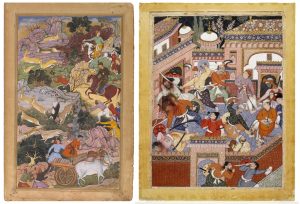

Left: “Hunting a cheetah,” La’l and Kesav Khord, illustration from the Akbarnama, c. 1586–89, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 33 x 20 cm (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London); Right: “Prison Break,” illustration from a Hamza Nama manuscript, 1562–77, Imperial Mughal school (Brooklyn Museum)

Other examples of such themes abound in Mughal art, such as a hunting scene from the Akbarnama which shows the decisive moment the cheetah tears into its prey (above left), or the scene of a prison break from the Hamza Nama manuscript, with blood spurting from the necks of those recently beheaded (above right). Yet the elephant hunt illustration is also more than a dynamic illustration of a charismatic emperor. In it we can see the new, innovative style distinct to Akbar and his court, where the personality of the ruler and a cosmopolitan blend of styles resulted in art that was unmistakably Mughal.

Additional resources

See the left and right pages of this work at the Victoria and Albert Museum.