Kamakura period (1185–1333 C.E.): new aesthetic directions

The earlier Insei rule gave way to an extra-imperial, although imperially sanctioned, military government, known in Japanese as bakufu. Military leaders—called shōguns—first came from the Minamoto family (whose headquarters in Kamakura gave the name to the period), then power concentrated in the (related) Hōjō family. Eventually, the Minamoto and Hōjō shōguns lost their respective control to internal struggles, the pressure of other clans, and an economy bankrupted by coastline fortifications undertaken in response to two (thwarted) Mongol and Korean invasions.

This binary system of government, comprising the shōgun’s rule and the (nominal) rule of the emperor, significantly contributed to a shift in aesthetic interests and artistic expression. The taste of the new military leaders was different from the aesthetic refinement that dominated Heian-period court culture. They embraced instead a sense of honesty in representation and sought works that emanated robust energy. This new development toward life-likeness and a form of idealized realism is particularly evident in portraiture, both two-dimensional and sculptural.

Left: Kamakura-period portrait of a revered monk (Portrait of Jion Daishi, 14th century, ink and color on silk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Right: Heian-period portrayal of courtier (Segment of illustrated scroll of the Tale of Genji, 12th century, opaque colors on paper, Tokyo National Museum). Note the difference in how the faces are depicted.

More detailed portraits of lay and religious leaders contrasted with the hikime kagihana (a line for the eye, a hook for the nose) practice of the Heian period, while narrative handscrolls differed from Heian-period Genji-themed pictures in their intricately detailed depictions of historical events. There is no better example than the episode of the “Night Attack on the Sanjō Palace” from the Scroll of Heiji Era Events; here, the visual richness resulting from the imagination of the scroll’s painter(s) makes the depiction appear brutally frank and viscerally impactful.

“Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace” (detail), Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki), second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Anonymous sculptor, portrait of Buddhist monk Chōgen, 1206, polychrome wood (Tōdaiji, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Unkei, Muchaku (Asanga), c. 1208-1212, polychrome wood (Kōfukuji, Nara, image: Sutori)

In sculpture, portrayals of revered monks reach an unprecedented degree of realism, whether modeled on the depicted figures or simply imagined. Sometimes the statues would have rock-crystal inlaid eyes, which heightened the immediacy of the figure’s presence.

The sculptor Unkei and his successors, especially Jōkei, created Buddhist sculptures, carved from multiple blocks of wood, whose facial and bodily features expressed not only an interest in life-likeness, but also a sense of monumentality, sheer energy, and visceral force.

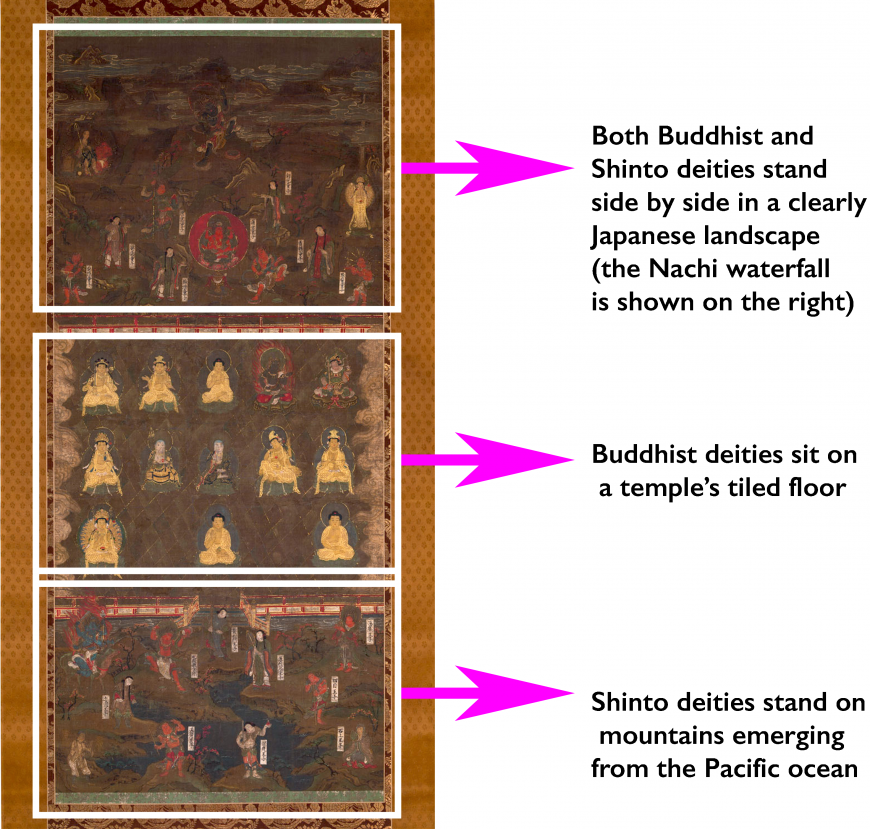

During the Kamakura period, the confluence or syncretism of Buddhism and the indigenous Shintō deepened. Paintings like the 14th-century Kumano shrine mandala contain representations of both Buddhist and Shintō deities, divided into registers that illustrate the fusion of the two world-views against the backdrop of famous sacred sites of Japan.

Kumano Shrine Mandala 熊野曼茶羅圖 (annotated), early 14th century, hanging scroll, ink, color, and gold on silk, image 131.9 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Additional resources:

For information on other periods in the arts of Japan, see the longer introductory essays here:

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)