Didarganj Yakshi, 3rd century B.C.E., polished sandstone, Didarganj Kadam Basul, Eastern Patna, India, c. 162 cm high (Bihar Museum, Patna, India; photo: Shivam Setu, CC BY-SA 4.0)

On October 18, 1917, Maulavi Qazi Sayyid Muhammad Azimul, a Muslim religious instructor, came across a large block of stone along the edge of the River Ganges while searching for a grinding stone. [1] As he began to dig away the dirt, he discovered that the block was, in fact, a pedestal for a giant, polished stone statue. When unearthed and set upright, the impressive image, about five feet two inches tall, must have awed Maulavi. The monumental sculptural figure came to be identified as a Yakshi, a female nature spirit, who embodies fertility and prosperity with her wide hips, full breasts, and an enigmatic smile. Today she is widely known as the “Didarganj Yakshi,” because she was discovered in Didarganj Kadam Basul, in northeastern India. Maulavi’s find has become one of the most celebrated and well-traveled of all Indian works of sculpture.

Didarganj Yakshi, 3rd century B.C.E., polished sandstone, Didarganj Kadam Basul, Eastern Patna, India, c. 162 cm high (Bihar Museum, Patna, India)

Didarganj figure

The sculpture (henceforth, the “Didarganj Yakshi”) was carved from Chunar sandstone, which has been burnished to create a lustrous polish on the sculpture’s surface (more on this below). The frontal stance of the Didarganj Yakshi does not distribute her weight equally on both legs; her right knee bends slightly while her weight shifts onto her left leg. Due to this, the posture of the legs gently carries through to an unusual movement in the upper body, as the figure bends her torso slightly forward. The forward movement of the body is naturalistic and demonstrates the skillfulness of the artist of the Didarjang Yakshi in capturing the body’s movement in the stone. She has delicate features, with arched eyebrows, large eyes, visible cheekbones, and small lips; however, her nose is chipped off—this damage may have been caused while she remained undiscovered at the bottom of the River Ganges.

Her ample breasts, slender waist, and wide hips accentuate her femininity. She wears finely detailed jewelry, including a jewel on the forehead, huge dangling earrings, multiple strands of necklaces, stacked bangles, a bejeweled girdle around her waist, and ornate anklets.

Didarganj Yakshi (detail), 3rd century B.C.E., polished sandstone, Didarganj Kadam Basul, Eastern Patna, India, c. 162 cm high (Bihar Museum, Patna, India; photo: Shivam Setu, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Her lower garment is carefully rendered with the folds of the fine material draped effortlessly and clinging closely to the legs. The folds fall thick and heavy at the center, covering her genitalia. Her left arm is missing, damaged over time (though likely it would have been shown at her side), while her right arm holds a long chowrie (fly-whisk) flung over the shoulder. The chowrie that she carries makes it impossible to ascertain the sculpture’s identity with absolute conviction—more on this later.

Didarganj Yakshi (detail), 3rd century B.C.E., polished sandstone, Didarganj Kadam Basul, Eastern Patna, India, c. 162 cm high (Bihar Museum, Patna, India; photo: Hpgoa, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A “Mauryan” sculpture par excellence

The Didarganj Yakshi was a significant find for the archaeologists and historians of the early twentieth century because of its incredible execution. Placing the sculpture in the history of the Indian subcontinent became important to understanding the evolution of the art of the region. Given that the sculpture was found without any indication about its original context, archaeologists and art historians have compared it to other sculptures with secure dating to help place the Didarganj Yakshi in a specific time period. At the time when the Didarganj Yakshi was found, scholars were deeply invested in building the chronology for the history of India—particularly the early centuries B.C.E. The most commonly suggested date for the sculpture is the third century B.C.E., based on the comparison with securely dated works from the third century B.C.E. that also feature highly polished sandstone and elaborate details such as those seen on the Didarganj Yakshi sculpture.

Left: Lohanipur torso, c. 3rd –2nd century B.C.E., polished dandstone, Patna, Bihar, India (Patna Museum, India); right: Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath, c. 250 B.C.E., polished sandstone, 210 x 283 cm, Sarnath Museum, India (photo: Chrisi1964, CC BY-SA 4.0)

For instance, the Didarganj Yakshi is now seen in the context of other stylistically similar sculptures, such as the Lohanipur torso, the lion Ashoka pillars, and the Rampurva Bull Capital, all of which are considered excellent examples of “Mauryan” sculpture. What do scholars mean by “Mauryan”? Mauryan sculptures are characterized by the high polish of the sandstone, an attention to detail in depicting naturalistic subjects, and the monumentality of the sculptures. The term “Mauryan” indicates that the sculptures were made during the “Mauryan dynasty,” which ruled a vast expanse of the Indian subcontinent between 322–185 B.C.E.

Map of the extent of the Maurya dynasty’s control in the 3rd century B.C.E. (underlying map © Google)

In the year 322 B.C.E., central and northern India, as well as parts of modern-day Iran, were united under the rule of Chandragupta Maurya, in the capital city of Pataliputra (modern Patna, Bihar). Subsequent rulers, such as Chandragupta’s grandson Ashoka, left lasting legacies in the Indian subcontinent.

Scholars of Indian art today tend to shun using dynastic labels, such as “Mauryan,” for works of art because dynastic classifications can presume that all art is produced under the patronage of the political ruler. However, what is interesting are the artistic innovations showcased by the sculptures of the period from the third to first century B.C.E. During this period, the most important innovation seems to have been the preference for stone over wood for sculpture and architecture. The most commonly used stone is the sandstone, especially the red-spotted or the “Chunar” sandstone, a reddish or buff-colored, finely grained, hard sandstone. The artists of the time harnessed the many qualities of the sandstone to produce excellent stone sculptures. The sandstone is fairly resistant to weathering, and the sculptures have stood the test of time. It is also a very easy stone to cut, making it possible for artists to carve in high relief and in the round, as well as to add extensive details to the sculptures, such as clothing, ornaments, and hairdos. These features of the sandstone made it possible for the artists to produce monumental stone sculptures with incredible detail.

Yet another technological development in the art of the late first millennium B.C.E. was the practice of burnishing the sandstone, which leads to a shiny glossy, lustrous polish on the surface, adding to the presence of the monumental sculpture.

For all the above mentioned features, the Didarganj Yakshi came to be accepted as “the high water-mark of Mauryan sculptural art.” [2]

A disputed identity: Yakshi or Ganika?

Who is this female carved in stone? For more than a hundred years, scholars have contested the sculpture’s identity. Over the twentieth century, the sculpture has been designated with a variety of identities—that of a goddess, or a yakshi (a female nature deity), or a ganika (a female royal attendant). [3] Her identity has been disputed due to the presence of the chowrie (fly-whisk), a device used to keep cool and keep insects away, which is both a common attribute for a yakshi and a ganika.

The case for identification as a yakshi

Due to her monumental size and frontal position, she has been associated with the group of protective guardian deities comprising yakshas (male spirit deities), yakshis (female spirit deities), and nagas (serpent deities) that we find from the third century B.C.E. onwards, when stone became the preferred choice of material for sculpture. In the early centuries, guardian deities were popular among devotees for health, weather, wealth, progeny, and similar concerns, and served as protectors of specific villages and towns.

Yaksha with chamara, c. 3rd–2nd century B.C.E., polished sandstone, h. 162 cm, Patna, now Indian Museum, Kolkata, acc. no. P1, photograph after Chanda 1927, pl. 4a-b

Sculptural evidence for such male and female deities is found in abundance. One of the earliest sculptural examples of a yaksha is a large-scale male figure from Patna, dated to about the same time as the Didarganj figure. The Patna figure is identified as a yaksha through the label inscription across the scarf on his left shoulder. [4] It is monumental in size, and displays the rigid frontality and equal (or near-equal) distribution of weight on both legs that we see with the Didarganj female figure. This yaksha also holds a fly-whisk in his right hand.

Left: Yakshi, 2nd century B.C.E., from Besnagar, Madhya Pradesh (Indian Museum, Kolkata); right: Bhutesvara Yakshis, 2nd century C.E., Mathura (Indian Museum, Kolkata; photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0)

Sculptures of yakshis from this time also appear similar to the Didarganj sculpture, including a female figure from Besnagar dated to the second century B.C.E. and those found on the railing pillars from Bhuteshwar mound, Mathura, dated to the early second century C.E. People worshipped yakshis in the context of fertility and prosperity. These monumental yakshis are nude and wear necklaces, anklets, and decorative girdles around their ample hips, just like the Didarganj sculpture.

Nagini (Snake Goddess), 1st century C.E., sandstone, 62 3/4 x 23 x 12 1/2 inches, carved in Mathura (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art)

There are also examples of life-size Nagini or female snake deities, all carved in the round in and around Mathura and dating from the first century B.C.E. to the first century C.E. These female nagini figures were a continuation of the same trend of large-scale free-standing sculptures of male and female deities which appeared around the same time as the Didarganj Yakshi in the third century B.C.E.

The wide range of sculptures of yakshas, yakshis, and nagas demonstrate the popularity of such images starting from the Mauryan period. Scholars have argued that the Didarganj figure must have been a yakshi due to her similarity in the stance, size, and disposition with other sculptures of yakshas and yakshis, and also because the chowrie (fly-whisk) was a common iconographic attribute of these guardian deities (though, notably, only found thus far on yaksha found at Patna. [5]

The case for identification as a ganika

Other scholars have offered a different interpretation of this figure, complicated by the presence of the chowrie (fly-whisk). In addition to being an attribute of a yakshi, the chowrie is also a common signifier of a courtesan (ganika) in the Indian tradition. Kautilya’s Arthashastra, a text of government from the Mauryan period, states that the ganika was appointed primarily to attend to the king—to hold the umbrella over his head, carry the water jug for him, fan him with a fly-whisk, and accompany him on processions. Given the ganika’s role as a highly placed royal courtesan of great talent and enviable accomplishments who fanned the monarch with a fly-whisk, it is possible that the sculpture—with its prominent fly whisk—is an image of a ganika.

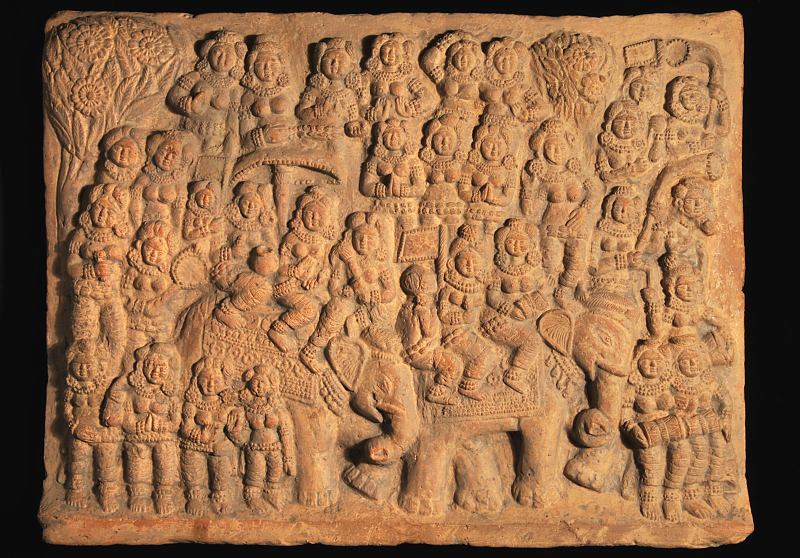

Procession Scene, Mauryan Period, terracotta, Chandraketugarh, India, 38 x 50 cm (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

In the Mauryan period, we find representations of female figures holding fly-whisks. In one example, we see a procession that depicts two giant elephants and a parade of women. We can spot a female holding a chowrie in the scene, seated on the elephant next to the king. [6] Examples such as this offer a glimpse into the role of the ganika in courtly life in the third century B.C.E. Scholars have argued that such images are evidence of the presence of ganikas at court during the Mauryan period, as described in the Arthashastra. The Didarganj Yakshi could have been a representation of a female attendant at court owing to the chowrie she holds in her hand.

These contrasting readings of the identity of the Didarganj sculpture as a yakshi or a ganika create confusion regarding who she was and what function she served. While scholars have yet to achieve consensus on who she might have been, the Didarganj female figure still is an exemplary example of sculpture from the Mauryan period and adds to our understanding of the artistic development during this time. However, she is most commonly known as the Didarganj Yakshi today, as that is the identity she assumed right after she was discovered from the bottom of the Ganges.

The afterlife of the sculpture

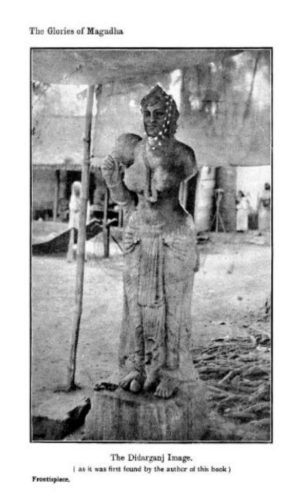

The sculpture enshrined shortly after discovery, from J. N. Samaddar, The Glories of Magadha, 1927

Shortly after Maulavi discovered the sculpture in 1917, the local people of Didarganj established a makeshift shrine, and started worshiping the sculpture as a Yakshi. [7] The deification of the sculpture in the twentieth century as a yakshi was not uncommon, as such large-scale male and female images were accepted by local people as guardian deities of their villages and towns. It is only natural that they made a shrine for their guardian deity. However, archaeologists and museum officials intervened to move the sculpture to a museum to study it for its date and iconography and ascertain her identity and context.

The sculpture was moved from the makeshift shrine to different locations until it found its home in the Patna Museum. [8] Stripped of all sacred connotations that the sculpture had assumed after its excavation, the yakshi in the museum would be reborn as the nation’s “most antique work of art” and “as one of the earliest visual statements of the Indian ideal of feminine beauty.” [9] Over time, the sculpture traveled to various exhibitions in the United Kingdom, France, and the United States to represent the art of Ancient India. However, when the Yakshi returned to India after the Sculpture of India exhibition in 1985, it allegedly bore a fresh pockmark-sized chip on her left cheek, leading to a massive outcry in the Indian media about the ethics of the international travel of such rare art treasures. [10] Its status as a national “art treasure” demanded that the sculpture be protected and conserved, available for viewing only in its original, national location. And so the Didarganj Yakshi remains in the Patna Museum, standing tall with her chowrie in hand, awaiting those who journey to the location to see her magnificence.