Emerald Buddha, 15th century, Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Sodacan, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In the early 19th century, a cholera pandemic raged across many parts of the globe, sickening and killing people—not unlike the COVID-19 pandemic today. In Thailand (known as Siam in the 19th century), King Rama II turned to Thailand’s protective deity, the Emerald Buddha, to create a “protective circle” to quell angry spirits, stop the spread of cholera, and maintain social order. [1] The 15th-century sculpture of the Emerald Buddha, measuring only 26 inches in height, is named after a mythical jewel and for its emerald green color—even though it is likely carved of jadeite. This small sculpture played an important role in helping to end the spread of cholera in Thailand.

Emerald Buddha (notice the different clothes he is wearing), 15th century, Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Ninara, CC BY 2.0)

The Emerald Buddha and Buddhist Kingship

The Emerald Buddha is a protective deity (another word for this is palladium). According to the Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha, a 15th-century mytho-historical chronicle, it was sculpted from a wish-granting jewel belonging to the Universal World Ruler (Chakravartin) in 44 C.E. by the celestial architect Vissukamma. Once carved into the likeness of the Buddha, the sculpture descended from heaven to earth and traveled throughout the Buddhist-practicing world. It availed itself to meritorious kings in India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand.

The chronicle goes on to describe the great wealth and happiness that was bestowed upon a kingdom that was able to house it. In the first epoch, the chronicle describes King Asoka’s enshrinement of the Emerald Buddha in Pataliputra, India:

From that time men and angels had all what they desired thoroughly satisfied by the Emerald Buddha. Men who had during their lives paid worship to him had their wishes granted.

However, when a king no longer lived by the dharma (the Buddha’s teachings), the Emerald Buddha would bring destruction to the kingdom and be transported to another land where the Buddha’s teachings were adhered to. In one example, the king of Angkor, Cambodia, lost his authority to enshrine the Emerald Buddha because of his decision to drown his son’s friend for accidentally killing the prince’s pet greenfly. As described in the second epoch of the chronicle:

There was a great hurricane, and none of all the inhabitants did remain alive except those on boats; and the king himself perished on that very day. Then a venerable priest took away the Emerald Buddha in a junk and with the guardians of the statue went North.

The chronicle is full of tales of how great prosperity and protection was brought to the devout who worshipped him.

Although the Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha is mostly mythological in content, this did not change the very real impact it had on Buddhist kingship in Thailand. Wars were fought between kingdoms over the enshrinement of the Emerald Buddha. Since its actual carving in the mid-15th century, the Emerald Buddha was understood to be a magical sculpture that could perform miracles (such as bringing forth rain during droughts), but more importantly, it had become a powerful object of legitimation. As described in the chronicle and as demonstrated in history, a king that possessed the Emerald Buddha could claim ultimate political and religious authority.

By the 19th century, the Emerald Buddha had been in the possession of the Chakri family since 1782. The Chakri dynasty (the current ruling dynasty of Thailand) has had continued custody of the Emerald Buddha, demonstrating their fortitude as Buddhist worshippers and as kings. The Emerald Buddha has been deployed on public occasions by the Chakri kings during times of celebration and calamity. In doing so, they continue to reinforce their roles as Buddhist sovereigns and the sculpture as a palladia object.

A note about Buddhism in Thailand

Material and archaeological evidence for Buddhist practice in the modern nation we now refer to as Thailand dates to the fifth-to-sixth centuries C.E. This is roughly a millennium after the invention of Buddhism in India. Today, more than ninety percent of the population self-identify as practicing Buddhists, and the kings of Thailand are required by law to worship the Buddha. Although different schools of Buddhism were introduced and adopted, Theravada Buddhism has been the dominant school in Thailand since the 13th century.

A cholera pandemic in the early 19th century and a Buddhist response

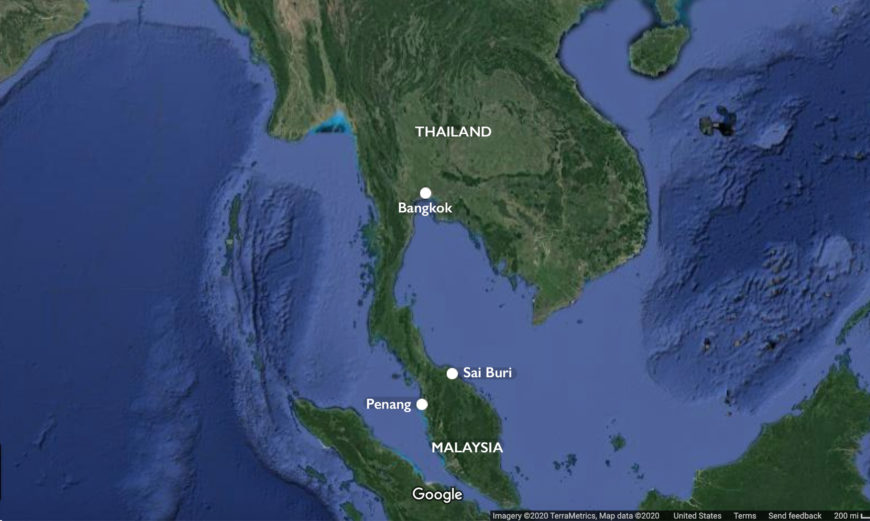

In 1817 Calcutta, India—then a British colony—a cholera epidemic turned into a pandemic that spread to the whole of Asia (including the Middle East, or West Asia), eastern Africa and parts of the Mediterranean coast. British Army and Naval officers, as well as merchants on trading ships, helped to spread cholera between their colonies and beyond. By 1820, cholera had spread to almost every corner of India, and had reached important trading ports in Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and China. It is estimated that a fifth of the population of Thailand died from the disease in less than one year. The Dynastic Chronicles of the Second Reign describes how communities were unable to handle the mass casualties, and that corpses were “heaped one upon the other like bales of cloth,” leading people to escape the horrors by traveling away from infected areas.

When medical treatments that included the ingestion of herbs did not help to quell the disease or prevent the death of those inflicted, King Rama II announced a royal decree on May 22, 1820. He declared that:

Great cannons would be fired the whole night until dawn. The Emerald Buddha and precious relics would be taken in procession on land and by boat by monks of the ratchakhana rank [appointed by the king] scattering sand and sprinkling lustral water. The king exhorted royalty, both from krom [princely] rank and without, as well as officials both high and low of the Front Palace and the Inner Palace, to suspend all duties and to stop all work…. He let them direct their attention to meritorious things, chanting Buddhist stanzas and gift-giving.

Temple complex with Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Preecha.MJ, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The decree goes on to command people to stop all travel, and cease the killing of animals.

King Rama II’s decision to deploy the Emerald Buddha—enshrined in his private temple, Wat Phra Kaew—served both a religious and a political purpose. First, since its invention, the Emerald Buddha was believed to have magical powers. Water that was lustrated (ceremonial washing) on the icon was believed to cure illness by ingestion or by touch. It therefore made sense that the icon would travel the kingdom “on land and by boat” with monks to purify affected communities with water that was blessed by the Emerald Buddha. When water was unavailable, sand sanctified by the icon was used. The sprinkling of both by monks, and the chanting of expiation sutras to push out evil spirits, created a literal boundary of protection.

Emerald Buddha, 15th century, Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Sodacan, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The second function of deploying the Emerald Buddha was to visualize the king’s religious authority. As outlined in the Chronicles of the Emerald Buddha, the mere presence of the sculpture could bring peace and happiness to a kingdom under the auspices of a devout ruler. As an object under his sole possession, King Rama II’s decision to have the Emerald Buddha publicly paraded during the cholera pandemic visualized his ability to return the country to a period of health and stability.

Cholera began to subside in Thailand by April 1821. At the time, the king and court’s decision to deploy the Emerald Buddha and enact protective state rituals were seen by the public as effective measures against the cholera pandemic. However, it was the government’s stay at home orders and the public’s awareness of the dangers of contaminated water that limited the actual spread of the disease. While cholera was not completely understood in 1820, intellectuals at court had become aware of European drugs that were used to combat diseases. By the reign of King Rama III (r. 1824–1851), vaccinations and Western medicine were used alongside traditional medical knowledge and treatments.

The Emerald Buddha in the age of COVID-19

The Emerald Buddha has yet to leave the royal chapel during the COVID-19 pandemic and so it has not been paraded through the streets of Bangkok. This is due, in part, to King Rama V (who ruled from 1868-1910) who banned the procession of important relics and the Emerald Buddha during times of catastrophe (he considered it superstitious and unfounded in scientific methods for combating natural disasters and diseases). Moreover, unlike most Buddhist temples in Thailand and elsewhere in Asia such as Todai-ji in Japan, Wat Phra Kaew where the Emerald Buddha is enshrined, is not attached to an active monastery overseen by monks or nuns. The icon is under the control of the royal household, which has continued to adopt the position of King Rama V. This has not, however, stopped worshippers from visiting the Grand Palace and Wat Phra Kaew to leave offerings or to pray to the Emerald Buddha.

Throughout history, as demonstrated by the 19th-century cholera pandemic in Thailand, Buddhist communities in times of peril have looked to such collective efforts to harness their anxieties into positive action.

Notes:

[1] B.J. Terwiel, “Asiatic Cholera in Siam: Its First Occurrence and the 1820 Epidemic,” in Death and Disease in Southeast Asia: Explorations in Social, Medical and Demographic History, ed. Norman G. Owen (Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia and Oxford University Press, 1987), 151.

[2] Camille Notton (trs.), The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha (Bangkok: Bangkok Times Press, 1931).

[3] Notton, 18.

[4] Notton, 27.

[5] Melody Rod-ari, “Origins of the Emerald Buddha Icon,” in Across the South of Asia: A Volume in Honor of Prof. Robert L. Brown, eds. Robert DeCaroli and Paul A. Lavy (New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, Ltd., 2020).

[6] “Thailand,” Central Intelligence Agency, accessed July 7, 2020, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/attachments/summaries/TH-summary.pdf.

[7] Terwiel, 154.

[8] Terwiel, 150.

Additional resources:

Learn more about southeast Asian art from LACMA

For the classroom

Discussion questions

While this essay focuses on themes of Buddhist ethics and kingship in response to the cholera pandemic in Thailand, it is a useful case study that allows students to make broader connections to ideas about effective leadership. Specifically:

- How have political leaders responded to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Have leaders and governments with strong religious ties been better able to meet the needs of their communities?

Moreover, colonization helped to spread cholera, turning it from an epidemic in Calcutta, India into a world-wide pandemic. Many have blamed globalization on the rapid spread of COVID-19.

- What is the future of economic and cultural globalization?

- Can we solve the many crises that have emerged from the pandemic without multi-national collaboration?