Kamakura period (1185-1333): new aesthetic directions

The Insei rule gave way to an extra-imperial, although imperially sanctioned, military government, known in Japanese as bakufu. Military leaders—called shōguns—first came from the Minamoto family (whose headquarters in Kamakura gave the name to the period), then power concentrated in the (related) Hōjō family. Eventually, the Minamoto and Hōjō shōguns lost their respective control to internal struggles, the pressure of other clans, and an economy bankrupted by coastline fortifications undertaken in response to two (thwarted) Mongol and Korean invasions.

This binary system of government, comprising the shōgun’s rule and the (nominal) rule of the emperor, significantly contributed to a shift in aesthetic interests and artistic expression. The taste of the new military leaders was different from the aesthetic refinement that dominated Heian-period court culture. They embraced instead a sense of honesty in representation and sought works that emanated robust energy. This new development toward life-likeness and a form of idealized realism is particularly evident in portraiture, both two-dimensional and sculptural.

Left: Kamakura-period portrait of a revered monk (Portrait of Jion Daishi, 14th century, ink and color on silk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Right: Heian-period portrayal of courtier (Segment of illustrated scroll of the Tale of Genji, 12th century, opaque colors on paper, Tokyo National Museum). Note the difference in how the faces are depicted.

More detailed portraits of lay and religious leaders contrasted with the hikime kagihana (a line for the eye, a hook for the nose) practice of the Heian period, while narrative handscrolls differed from Heian-period Genji-themed pictures in their intricately detailed depictions of historical events. There is no better example than the episode of the “Night Attack on the Sanjō Palace” from the Scroll of Heiji Era Events; here, the visual richness resulting from the imagination of the scroll’s painter(s) makes the depiction appear brutally frank and viscerally impactful.

“Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace” (detail), Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki), second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Anonymous sculptor, portrait of Buddhist monk Chōgen, 1206, polychrome wood (Tōdaiji, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Unkei, Muchaku (Asanga), c. 1208-1212, polychrome wood (Kōfukuji, Nara, image: Sutori)

In sculpture, portrayals of revered monks reach an unprecedented degree of realism, whether modeled on the depicted figures or simply imagined. Sometimes the statues would have rock-crystal inlaid eyes, which heightened the immediacy of the figure’s presence.

The sculptor Unkei and his successors, especially Jōkei, created Buddhist sculptures, carved from multiple blocks of wood, whose facial and bodily features expressed not only an interest in life-likeness, but also a sense of monumentality, sheer energy, and visceral force.

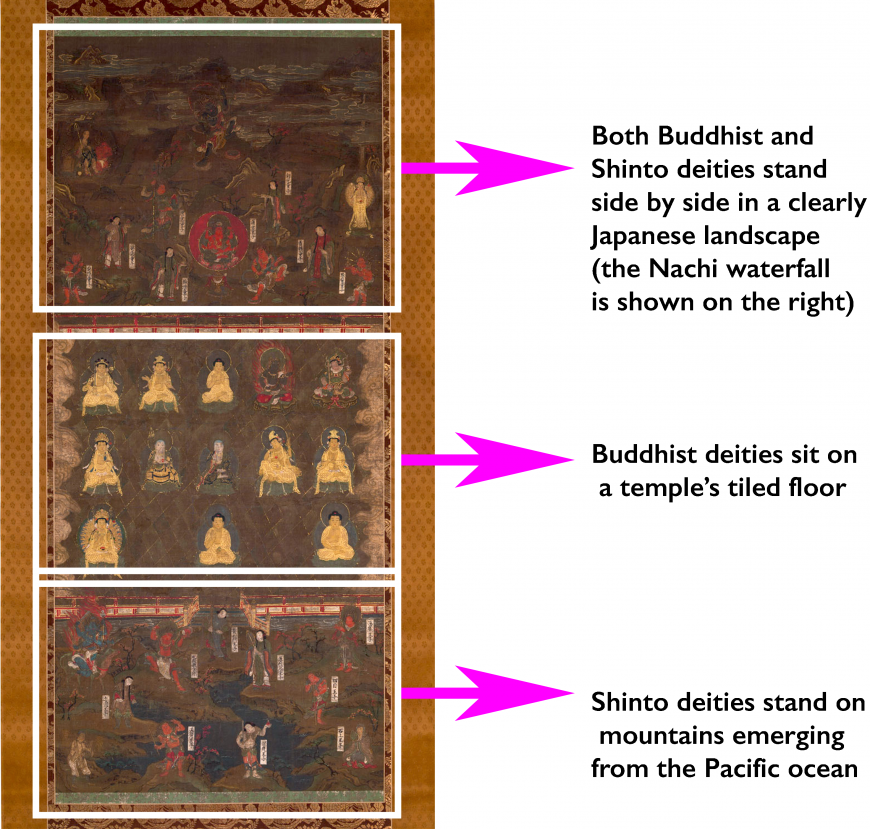

During the Kamakura period, the confluence or syncretism of Buddhism and the indigenous Shintō deepened. Paintings like the 14th-century Kumano shrine mandala contain representations of both Buddhist and Shintō deities, divided into registers that illustrate the fusion of the two world-views against the backdrop of famous sacred sites of Japan.

Kumano Shrine Mandala 熊野曼茶羅圖 (annotated), early 14th century, hanging scroll, ink, color, and gold on silk, image 131.9 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Nanbokuchō (1333 – 1392) and Muromachi (1392 – 1573) periods:

Zen principles, ink painting, and elegant beauty

The Muromachi period, coinciding with the rule of Ashikaga shōguns, was one of the most turbulent and violent in Japanese history. It started with the Nanbokuchō (“the period of the southern and northern courts”), during which political power was split between the Ashikaga-controlled “northern” court and the “southern” and short-lived court of emperor Go-Daigo. The Muromachi period also included the Sengoku (“the age of the country at war”), a period of warfare and chaos in the aftermath of the Ōnin war (1467-1477), triggered by rivalry between provincial warlords.

Zen Buddhist temple Rokuonji, commonly known as Kinkakuji/ Golden Pavilion, originally a villa, first built 1397, reconstructed 1955 (Kyoto, image: Foto Captor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Two of the Ashikaga shōguns, Yoshimitsu (14th century) and Yoshimasa (15th century), are associated with the Kitayama and Higashiyama cultures, respectively—two sub-periods of cultural efflorescence that nurtured important developments in Japanese arts across mediums. Kitayama culture, so named after an area north of Kyoto where Ashikaga Yoshimitsu had a golden pavilion—Kinkakuji 金閣寺—built for his retirement, is known for the emergence of Noh and the increased influence of Zen Buddhism and Chinese ink painting.

Art coming from contemporaneous Ming-dynasty China as well older Chinese art—dating from the Song and Yuan dynasties, such as the works of Muqi (Mokkei 牧谿 in Japanese)—deeply influenced Japanese arts, especially the emerging local tradition of ink landscape painting.

Muqi (active 13th century), Kannon framed by Crane and Gibbons, three hanging scrolls, ink and light color on silk, 174.2 cm x 98.8 cm (Kannon). Japanese artists like Hasegawa Tōhaku, who traced their stylistic roots to Sesshū, had opportunities to study these paintings at a Buddhist temple in Kyoto where they have been housed for centuries (Daitokuji)

The most influential Japanese ink master, the 15th-century painter and Zen monk Sesshū Tōyō combined, in his works, Zen principles and lessons learned from Song-dynasty Chinese ink painting—most notably a double sense of austerity and immediacy, highly admired by the Ashikaga shōguns and the samurai class who embraced Zen Buddhism.

Sesshū, Splashed-Ink Landscape (or Broken-Ink Landscape, haboku sansui zu破墨山水図), 1495, ink on paper, 148.6 × 32.7 cm (full scroll) (Tokyo National Museum, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Sesshū was a celebrated artist in his own lifetime and continued to be revered as a model by later generations of painters. He became a Zen Buddhist monk at a young age and his master taught him both about Zen and about Chinese ink painting. To perfect his understanding of both, Sesshū traveled to China, where he was honored as a distinguished guest. It is believed that he painted in both palatial and monastic contexts. Upon his return to Japan, he laid the foundation for a new era of Japanese ink painting that straddled religious and lay patronage and combined Chinese and Japanese stylistic elements.

Over the centuries, painters emulated Sesshū’s style, especially his “splashed ink” or “broken ink” technique, and its roots in the literati tradition, some even affixing the painter’s seal to their works, all in an attempt to follow into the footsteps of a revered artist and to attract patrons. The Unkoku school strategically considered its painters to be in the direct lineage of Sesshū. The Hasegawa school similarly traced its stylistic genealogy to Sesshū. These two schools are just two of many examples of Japanese artists embracing a stylistic lineage, whether real or construed, leading back to Sesshū or another master. Legitimizing genealogies are a hallmark of Japanese art history.

The advancement of ink painting under the influence of Sesshū is part and parcel of the second Ashikaga-patronized sociocultural sub-period—the so-called Higashiyama culture, named after an area east of Kyoto, where the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa had a silver pavilion—Ginkakuji 銀閣寺—built for his retirement.

The Higashiyama culture entailed programmatic patronage of the arts. During this period, the Kanō school of painting is established and its founder, Masanobu, is appointed official shogunal painter in the late 15th century. At this early stage, Kanō school painting is particularly indebted to Chinese ink painting and the Chinese bird-and-flower tradition. Masanobu’s son, Kanō Motonobu, widened the school’s painting repertoire by introducing color and indigenous motifs and thereby laid the foundation for an appealing synthesis of Chinese and Japanese elements.

Kano Motonobu, Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, 16th century, pair of folding screens, ink, color, and gold on paper, 162.4 × 360.2 cm each (Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum, Kobe)

The imperial court had its own favored line of painters, who worked in the yamato-e tradition and often specialized in pictures drawn from the Tale of Genji. (Both yamato-e and the Tale of Genji are described in the section on Heian-period art.) These painters are known as the Tosa school; the earliest mention of a painter named Tosa dates from the early 15th century and refers to a painter who was also the governor of the Tosa province. Contemporaneous with the beginnings of the Kanō school was Tosa Mitsunobu, who expanded his school’s repertoire much like Kanō Motonobu did for his school, except in opposite directions: while the Kanō artist added elements of traditional Japanese painting, the Tosa artist began to incorporate elements of Chinese painting. In this sense, the two schools created separate versions of a Chinese-Japanese stylistic synthesis, with the Tosa relying more heavily on the Japanese tradition and the Kanō, on the Chinese.

Storage jar, 14th-15th century, stoneware with natural ash glaze, Shigaraki, 46.7 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

At the same time, the tea ceremony (chanoyū 茶の湯) emerged as a ritualized form of preparing and enjoying powdered green tea. For this ritual, domestic ash-glazed stoneware vessels, coiled by hand and fired in wood-burning kilns, began to be favored for their austere elegance or sense of sabi 寂—an important Japanese aesthetic concept that stands for seeking beauty in what is simple, solitary, and withered.

These different art forms and mediums—painting, ceramics, dramatic performances, collaborative poetry-writing parties, and tea rituals—converged in shogunal residences like the Golden and Silver Pavilions and especially in the decor of these residences, governed by the aesthetic principle of fūryū 風流—another enduring aesthetic notion in Japan, referring to a refined taste that favors rarified elegance and sensual beauty.

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1615):

palatial opulence, bold expression, and the beauty of the imperfect

Reconstruction of main keep of Azuchi Castle (Ise Azuchi-Momoyama Bunka Mura, image: Wikimedia Commons)

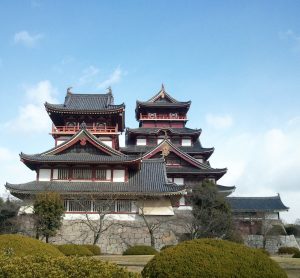

The Azuchi-Momoyama period gets its name from the opulent residences of two warlords who attempted to unify Japan at the end of the Sengoku (“warring states”) era, namely Oda Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle and Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Fushimi or Momoyama Castle. Both castles were not only martial structures for strategic warfare and defense, but also luxurious mansions meant to impress and intimidate political rivals. The architectural style of these residences derived from that of the pavilions built by Ashikaga shōguns during the previous historical period. Also, both castles’ locations were carefully selected for their optimal proximity to the capital—Nobunaga’s castle was built just outside of Kyoto on the shores of lake Biwa, while Hideyoshi’s was in Kyoto itself, in the southeastern ward of Fushimi.

That the two castles were built only 20 years apart reveals the rapid succession of consequential political events that defined the Momoyama period: Oda Nobunaga rose to power starting in 1560 and by 1582, when he was betrayed by his own retainers, he had managed to gain control of most of Japan’s main island of Honshū.

Fushimi-Momoyama castle, built 1594, rebuilt 1964 (Fushimi Ward, Kyoto, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Nobunaga’s warrior, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, succeeded him and used his strategic thinking and negotiation skills to continue the efforts of unification, besides twice invading Korea (in 1592 and 1597). He was succeeded by another former retainer of Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who managed to secure unprecedented power in 1600, winning the most important of Japanese feudal battles, that of Sekigahara.

Only three years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed shōgun by the emperor and spent the remainder of his years consolidating the Tokugawa shōgunate, which would become a 250-year rule of relative peace and prosperity. Only forty years had passed from Nobunaga’s ascension to power to Ieyasu’s appointment as shōgun, but these were years filled with momentous change.

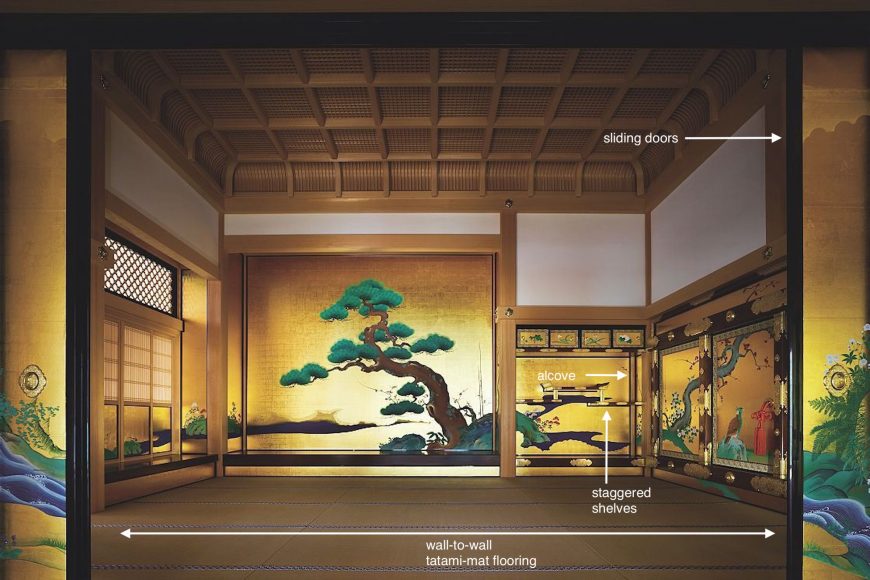

Like other opulent residences of its time, the Azuchi castle comprised numerous buildings in the shoin 書院 architectural style, developed in the Momoyama period. This style entailed a main area flanked by aisles, wall-to-wall tatami-mat flooring, square pillars, and various types of sliding doors and walls that partitioned and reconfigured space. Shoin also featured an alcove in the reception room, known as tokonoma, and elements developed in the Muromachi period for shogunal residences such as staggered shelves and a built-in desk.

Jodan-no-ma (feudal lord’s audience chamber), Honmaru Palace, Nagoya Castle, first built 1615 for Tokugawa Ieyasu’s son, reconstructed 2009-18 (image adapted from: japan-guide)

Kano Eitoku, Chinese lions, 16th century, six-fold screen, color and gold on paper, 223.6×451.8 (Sannomaru, Imperial Household Agency, Japan)

In addition to displaying the power of their owners, Nobunaga’s and Hideyoshi’s castles featured the bold and expressive art that characterized the Momoyama period, perhaps mirroring the energy and courage of the era’s military leaders.

Nobunaga’s Azuchi castle was adorned with the highly expressive paintings of Kanō Eitoku, the grandson of Motonobu, the Kanō painter who established the synthetic Chinese-Japanese aesthetic of the shōgun-patronized school. The very few surviving paintings of Eitoku exemplify this painter’s innovative approach to painting, characterized by dynamic compositions, bold and expressive brushwork, oversized animals, and imagery drawn from nature but set against an opulent golden background that would shimmer in the relatively dark interiors of the warlords’ residences. It can be said that Eitoku’s style matched the power that the painter’s patrons had and wished to put on display.

Hasegawa Tōhaku, Pine trees, 16th century, ink on paper, pair of six-fold screens, 156.8 x 356 cm (Tokyo National Museum)

A rival of the Kanō school emerged in the person of Hasegawa Tōhaku, who may have studied both with Kanō painters and with a pupil of Muromachi-period ink master Sesshū. Tōhaku eventually claimed to be a descendant of Sesshū and developed a bold and highly expressive style, working typically in monochrome ink. His ties to influential tea masters and Zen teachers helped him secure important commissions. Another artist who received major commissions, alongside Kanō Eitoku and Hasegawa Tōhaku, was Kaihō Yūshō, whose military experience and Zen Buddhist training influenced his unique brand of highly charged compositions combining dramatic ink washes and unusually long brushstrokes.

Kaihō Yūshō, Dragons and clouds, 1599, ink on paper (Ken’ninji, Kyoto, image: Japan Times)

Clog-shaped tea bowl with plum-blossom motifs and geometric patterns, early 17th century, stoneware with iron-black glaze, Mino ware, black Oribe type, 7.6 x 14.3 cm, diameter of foot 5.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

At the intersection of impressive palatial architecture and powerful ink paintings was another art form, nascent in the Muromachi period—the tea ceremony or chanoyu 茶の湯. In the second half of the 16th century, the tea master Sen no Rikyū revolutionized the practice of tea by modeling it on wabi, an aesthetic concept closely related to that of sabi. Wabi refers to finding beauty in simple, even humble things. Embracing the spirit of wabi and sabi, a disciple of Sen no Rikyū, Furuta Oribe, actively supported a new type of local ceramics that became so intertwined with Oribe’s style and efforts that they came to be known as Oribe ware. These new ceramics were radically different in a number of ways. First, they were locally produced and became popular enough to compete with Chinese ceramics in the aesthetic hierarchies of tea masters. Second, they are characterized by a distinctive practice of intentionally distorting the shapes of the vessels in response to the wabi aesthetic that valued the imperfect.

The Momoyama period is also remembered for intensified contact with other cultures. Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch ships landed in the Southern island of Kyushu and brought to Japan previously unknown markets, objects, and concepts; firearms, for example, were introduced by the Portuguese as early as 1543. International trade and the spread of Christianity were regarded with suspicion and therefore short-lived, culminating in the self-isolation policy instituted by the Tokugawa. However, trade continued with the Chinese and the Dutch, and a small number of Christians continued to practice in secret.

Nanban folding screen (one of a pair), Arrival of the Europeans, first quarter of the 17th century, ink, color, and gold on paper, 105.1 × 260.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Despite its brevity and limitations, the late 16th-century encounter with Europeans had a lasting influence. In the port of Nagasaki, Japanese artists were able to observe the foreign visitors’ dress, manners, and habits, and a new painting genre emerged, the so-called nanban (literally, “Southern barbarians,” the name given in Japan to the Europeans who arrived from India via a Southern sea route). Nanban paintings depict not only European priests and traders, but also Goanese sailors, who traveled with the merchants and missionaries, and even Caucasian women, although there were no women among those who landed in Japan at the time. Nanban screens became very popular and many copies were made, increasingly more removed from first-hand observations and reliant upon the painters’ imagination.

Writing box with Nanban figures, 1633, black lacquer with gold and silver maki-e, polychrome lacquer, and gold and silver foil inlay, 4.76 × 22.23 × 20.96 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Nanban imagery was not confined to painted folding screens; we encounter nanban motifs in other mediums such as ceramics and lacquerware. The inside of the writing box shown here presents images of Portuguese and Indian or African figures, while the outside is decorated with traditional Japanese motifs of fallen cherry blossoms. Objects such as this writing box exemplify not only the integration of nanban imagery in Japanese visual culture, but also an important Japanese aesthetic principle, that of kazari. Translated as both “ornament” and “the act of decoration,” kazari is also a mode of display—and so much more than that. Above all, kazari is an organizing principle of aesthetic and social dimensions that seeks visually and conceptually stimulating juxtapositions that transform the appearance of both objects and spaces, activating the viewer’s own creativity and imagination.

Additional resources:

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)