Seated Mother Goddess, Indus Civilization, c. 3000–2500 B.C.E., Mehrgarh style, terracotta, Baluchistan, Pakistan, 13.3 x 4.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Anthropomorphic and male and female human forms have been excavated from several sites associated with the Indus Valley Civilization.

These are subset of the various figurines that were made of fired clay or terracotta that contained sand, shell fragments, mica particles, and vegetable material. Despite variations in size—most are similar in size to the Indus Valley terracotta animal figurines and range from approximately 6 centimeters up to 30 centimeters—they have overarching similarities in compositional characteristics with specific differentiators based on their period and region of origin. Broadly, these figurines constitute a larger collection that also includes mythic forms (such as of unicorn-like creatures) and modular forms (such as of objects having moving parts).

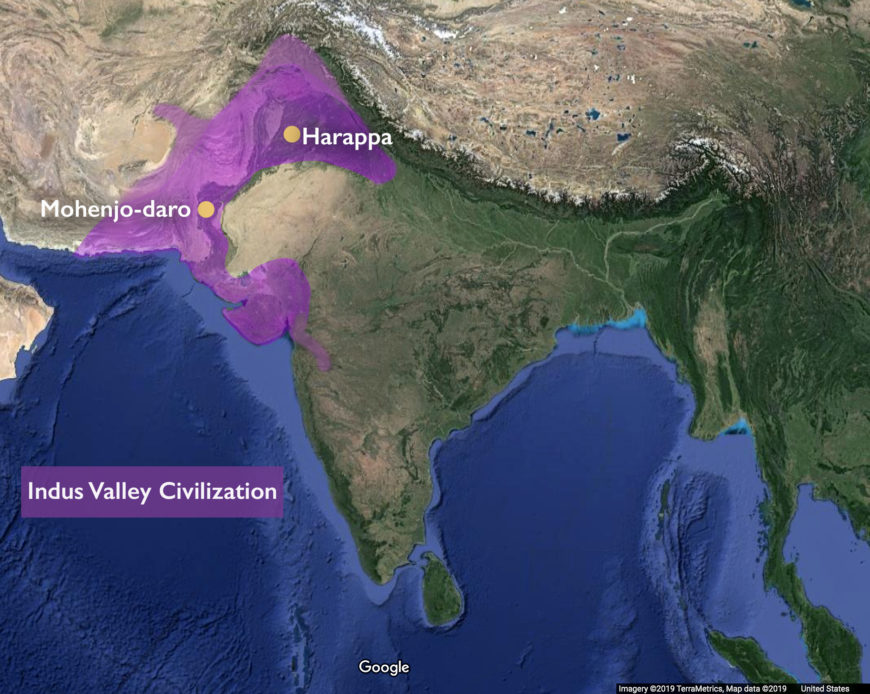

Evidence suggests that some early Indus figurines (excavated mostly from the Mehrgarh and Nausharo sites), date as far back as c. 7000 B.C.E.—prior to the Early Harappan Phase. The large hoard of figurines excavated from the Harappa and Mohenjo-daro sites in Pakistan suggest that their production reached a peak during the Mature Harappan Phase of the Civilization. The diversity in the compositional aspects of the figurines from both phases also alludes to possible trade and movement of people between present-day India and Iran.

Dog from Harappa, 2600–1900 B.C.E., terracotta, 1.9 x 5.3 x 3.3 cm (© Richard H. Meadow, Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan)

Although there is an overarching compositional continuity between these depictions and those from earlier periods, the newer figurines exhibit much greater diversity and distinctiveness in terms of their subject matter and style. Those from the Early Harappan Phase and earlier commonly featured seated females with wide hips, conical or disc-shaped breasts, joined feet and simple, unarticulated faces (such as the figure above). Leading up to the Mature Harappan Phase, however, there was a transition from seated to standing postures, with generic anthropomorphic and male figurines featuring more prominently—though less so than female figurines.

It is possible to see the attached ear ornaments and the double voluted headdress, in these figures, as well as the slightly figure-8 shape in the center figurine with the tapered waist. Fragments of terracotta figurines, Mohenjo-daro (Pakistan), Mature Harappan Period, c. 2600–1900 B.C.E., terracotta (The British Museum, photo: Zunkir, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Scholars have classified the female figurines from the mature phase into two broad categories: the early classic form and the later, figure-eight form. The early classic figures typically feature flat bodies adorned with attached ear ornaments and neck ornaments, such as chokers and necklaces, embellished with beads or pendants. The figure-eight forms are more rounded and lack ear ornaments and mouths.

These two categories, although differing in their overall form, bear several common characteristics. The standing females are usually depicted holding an infant or with their elbows arched outwards and their hands on their hips. Also typifying this group of figurines are conical breasts and mostly uncovered torsos that are girded at the hips with a decorative belt and a short skirt-like piece of clothing that covers the genitalia. The most notable features, however, are the elaborate hairstyles and the distinctive fan-shaped headdresses, which has been of particular interest to scholars. In contrast to most hairstyles and headwear that were typically devoid of decoration, the fan-shaped headdresses—the real-life equivalents of which were thought to have been fashioned out of textiles or even hair—were multiform due to the application of various decorations like cones, flowers, ropes, tiaras, panniers and double-voluted ornaments.

Terracotta figure, Harappa (Pakistan), Indus Valley Civilization (National Museum, New Delhi; photo: Gary Todd)

The less numerous male figurines, mostly from the Mature Harappan Phase, are distinguished by their slender form, exaggerated disk-like nipples, headdress and, occasionally, a beard. Exposed genitalia are more common among the earlier seated figurines than the later standing ones. The distinctive male headdresses are usually characterized by double-buns or horns that may be pointed, V-shaped or curved. Depicted sometimes with corded neck ornaments and a loincloth or skirt; and in rarer cases as having both male, female, or indistinct attributes—as renderings of infants and children—the gender of the figurines is sometimes ambiguous.

Terracotta figures, c. 2500 B.C.E. Indus Valley Culture, Chanhu Daro, Pakistan (Brooklyn Museum)

Compared to the human figurines, the anthropomorphic ones are relatively fewer in number and are typically represented as carrying oval or cylindrical objects, believed to represent musical or ritualistic instruments. These figurines, like the former, have been discovered both independently and as a part of larger domestic scenes, in which they are seated on beds, stools, or carts, with some engaged in manual work such as grinding.

Unlike the tablets of the time that were made from molds, these figurines were hand modeled, likely using three techniques: pinching, used to create sharper ridges for facial features; appliqué, used to attach clay shapes—for eyes, eyebrows, lips, breasts and jewelry—to the main figure; and incision, used to produce designs and patterns by carving into wet clay. Interestingly, the figurines typically had flattened backs and uneven feet, possibly an intentional feature, which rendered them unable to stand unsupported and allowed only frontal viewing.

Almost all terracotta figurines from this period were created out of two vertically joined halves of fine clay, which may have been sourced from the beds of rivers and lakes in the region. Scholars believe that the process and intention behind their creation may have also had a symbolic resonance—the two vertically joined halves, for instance, connoting a Harappan concept of dualism and self-integration, or the conceptual melding of the male and female.

Terracotta figures, Harappa (Pakistan), Indus Valley Civilization (National Museum, New Delhi; photo: Gary Todd)

Differing interpretations of this group of terracotta objects, particularly the female figurines, offer different attributions. Some scholars propose a cultural or ceremonial significance and others cite religious symbolisms, some dubiously claiming the figurines to be representations of a Mother Goddess cult. As with so many other cultural artifacts uncovered from the Indus Valley sites, the purpose and meaning of the terracotta human figurines remains a mystery, in large part due to the fact that the Indus script has not yet been fully deciphered.

In total, around 8,500 fragments of figurines have been excavated since 1920, most of which were found in a broken state attributed to wear-and-tear and trampling. Although the figural content of these fragments—now scattered across museums in India, Pakistan and Europe—fail to provide definitive insights, the stylistic and material aspects of the Indus Valley terracotta figurines provide the basis for a broad understanding of the life and material culture of Indus Valley Civilization.

Additional resources

Indus Valley terracotta animal figurines from The MAP Academy.

Mother Goddess representations from The MAP Academy.

T. Richard Blurton, Hindu Art (London: British Museum Press, 1992).

Sharri R. Clark, “Representing the Indus Body: Sex, Gender, Sexuality, and the Anthropomorphic Terracotta Figurines from Harappa,” Asian Perspectives, volume 42, number 2 (Fall 2003), pp. 304–28.

Sharri R. Clark, The Social Lives of Figurines: Recontextualizing the Third-Millennium-BC Terracotta Figurines from Harappa (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press, 2017).

Sharri R. Clark, “Material Matters: Representation and Materiality of the Harappan Body,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, volume 16, number 3 (2009), pp. 231–61.

Timothy Insoll, The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Jane McIntosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2008).

Gregory L. Possehl, The Indus Civilization: a Contemporary Perspective (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2002).

Female figurine with a fan-shaped headdress from Harappa

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy