The courtyard of the Qutb mosque, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0). In the foreground are pillars of the colonnaded walkway and in the background is a c. 4th – 5th century iron pillar and the mosque’s arched screen and prayer hall.

Layers of cultural, religious, and political history converge in the Qutb archaeological complex in Mehrauli, in Delhi, India. In its beautiful gateways, tombs, lofty screens, and pillared colonnades is a record of a centuries-long history of artistic vision, building techniques, and patronage. At the heart of the Qutb complex is a twelfth century mosque— an early example in the rich history of Indo-Islamic art and architecture.

The Qutb mosque is important for our understanding of the early part of the Delhi Sultanate (1206 – 1526), a period when new rulers would seek to cement their authority and legitimacy as kings in northern India. “Delhi Sultanate” is a collective term that refers to the Turko-Islamic dynasties that ruled, one after the other, from Delhi. [1] The monuments discussed in this essay were built by the three earliest rulers of the Sultanate. [2]

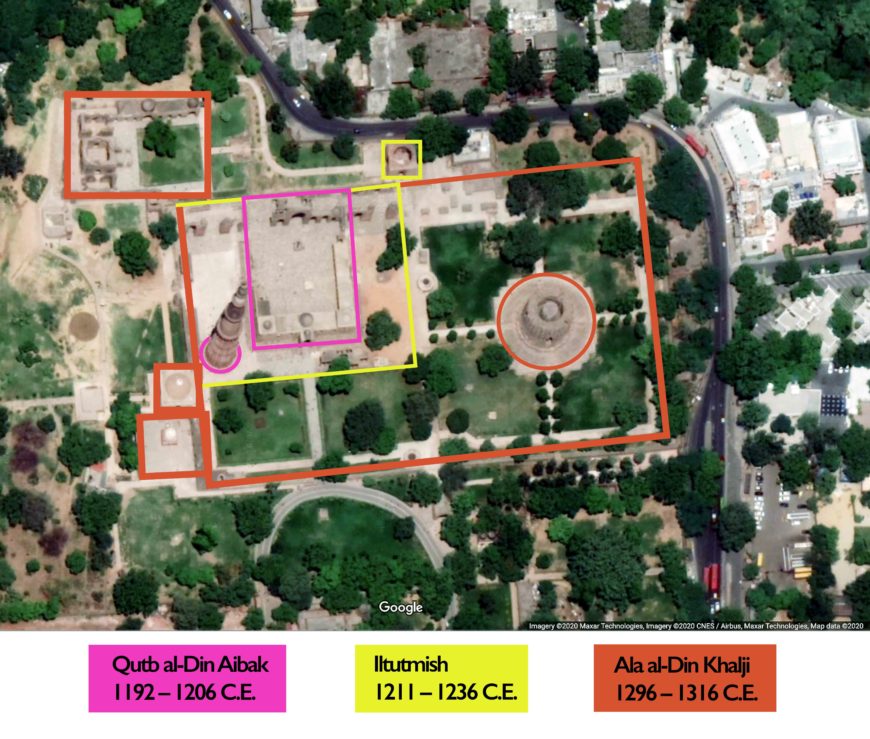

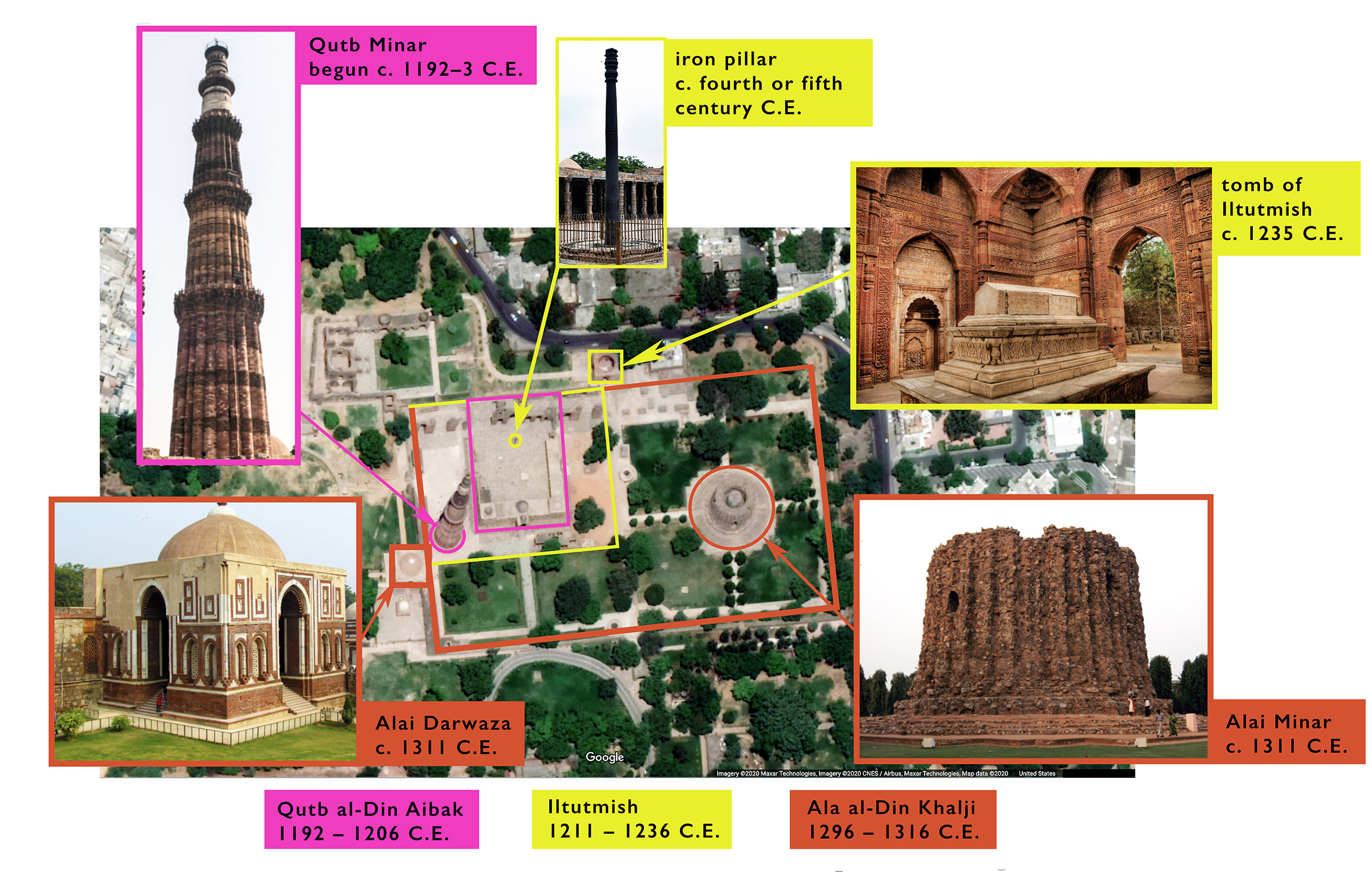

Plan of the Qutb complex showing the phases of construction of select monuments (photos: clockwise from top, Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0; Bikashrd, CC BY-SA 4.0; Kavaiyan, CC BY-SA 2.0; Alimallick, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In addition to the mosque, this essay discusses the following structures in the Qutb complex of monuments:

-

- the iron pillar

- Qutb Minar

- the tomb of Iltutmish

- the Alai Darwaza

- and the Alai minar

The 238 foot tall Qutb Minar in the background, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The first Sultan of the Delhi Sultanate

Before Qutb al-Din Aibak was the first sultan of the Delhi Sultanate, he was a Turkic military slave and a general in the army of the Ghurid dynasty of Afghanistan. He played an important role in conquering Delhi in 1192, as part of the territorial ambitions of the eleventh century Ghurid ruler Muhammad Ghuri.

As the Ghurid administrator in Delhi, Aibak oversaw the building of congregational mosques, including the Qutb mosque. The mosque is believed to have been built quickly as a matter of necessity—not only would the Ghurid forces have needed a place to pray, but a mosque was crucial for the proclamation of the name of the ruler during the weekly congregational prayer. In this context, such proclamations would have affirmed the legitimacy of Muhammad’s Ghuri’s right to rule.

Stylistic influences that define early Delhi Sultanate architecture

Islamic monuments in South Asia did not begin with the Delhi Sultanate; mosques were built when Islam was introduced in Sindh (in present-day Pakistan) in the eighth century as well as for Muslim merchants and communities who lived in various ports and towns across the subcontinent. Few of these structures have survived however and the Qutb mosque holds the distinction of being the oldest mosque in Delhi, an early example of Islamic architecture in India, and one that synthesizes Persian, Islamic, and Indian influences.

Qutb al-Din Aibak had come to India from Afghanistan and was familiar with its diverse architectural landscape. Afghanistan’s architecture in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries reflected both its pre-Islamic and Islamic history, as well as cultural exchange with Central Asia and India. Historians also describe the court of the Delhi Sultanate as Persianized, because it made use of the Persian language, literature, and Perso-Islamic art and architecture.

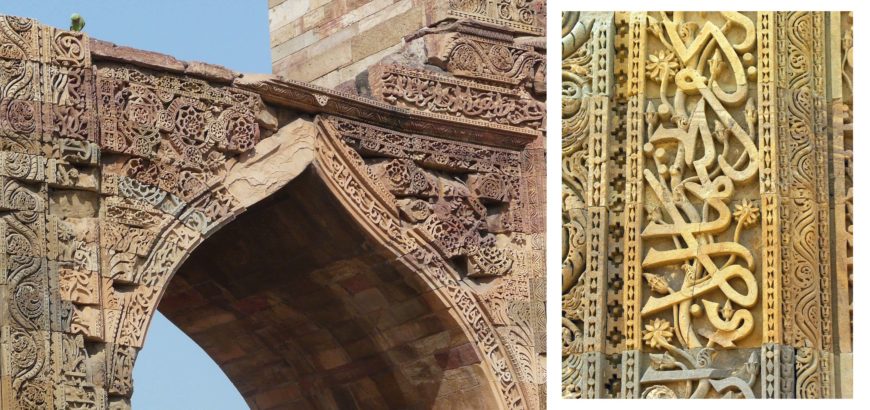

The architecture of the Delhi Sultanate is notable for its stylized decorative ornament which seamlessly incorporates features from Islamic artistic traditions such as arabesques (intertwining and scrolling vines), calligraphy, and geometric forms with Indian influences such as the floral motifs that adorn the calligraphy in the Qutb complex minar (tower) below.

Detail of the Qutb Minar, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

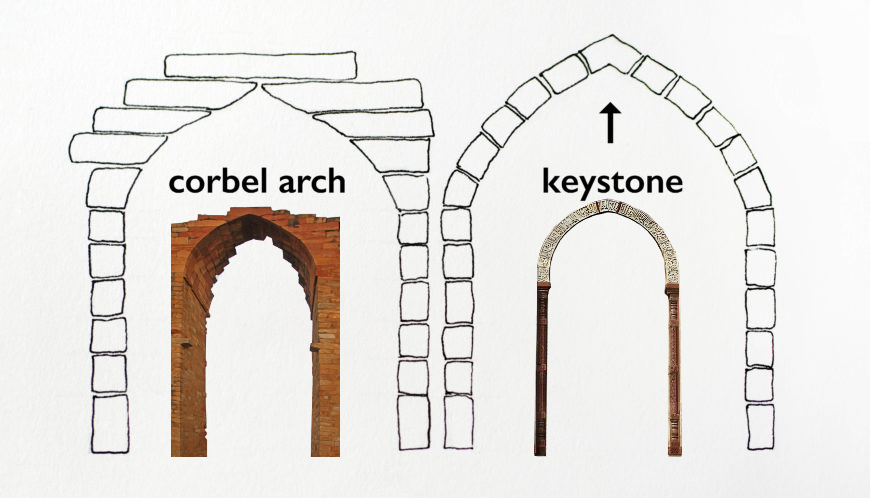

The hand of the Indian mason is discernible in the post and lintel and corbeling methods of construction employed in the earliest monuments in the complex, namely the Qutb mosque colonnade and prayer hall, its screen, and Iltutmish’s tomb. Later monuments at the Qutb complex (such as the fourteenth-century gateway Alai Darwaza) show a shift towards building techniques common in Islamic architecture outside of India. Arches in the Alai Darwaza, for instance, are not corbeled, but rather built with a series of wedge-shaped stones and a keystone.

A corbeled arch on the left (inset: Qutb mosque screen, dated 1198) and arch with a keystone on the right (inset: entrance to the Alai Darwaza, dated 1311). Photos: Gerd Eichmann, CC BY-SA 4.0; Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0).

Entrance into the Qutb mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi

The Qutb mosque and architectural re-use

The main entrance into the mosque today is on its east side. This arched doorway leads to a pillared colonnade and an open-air courtyard that is enclosed on three sides. Directly across from the main entrance, at the far end of the mosque, is an iron pillar, a monumental stone screen, and a hypostyle prayer hall.

Pillars, ceilings and stones from multiple older Hindu and Jain temples were reused in the construction of the colonnades surrounding the mosque’s open courtyard and in the prayer hall. Since the desired height for the colonnade did not match the height of older temple pillars, two or three pillars were stacked, one on top of the other, to reach the required elevation.

A view of a temple ceiling (constructed in the post and lintel and corbel technique) and pillars in the colonnaded walkway of the Qutb mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Divya Gupta, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Indian temple pillars are often adorned with anthropomorphic figures of deities and divine beings, mythical zoomorphic, and apotropaic motifs, as well as decorative bands of flowers. A belief by the builders of this mosque in a proscription against the portrayal of living beings is evident in the removal of the faces carved in the older stonework. Other decorative motifs were left untouched, likely for their apotropaic and ornamental qualities.

View of pillars in the colonnaded walkway (left) and pillar detail with faces obscured (right), Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photos: Johan Ekedum, CC BY-SA 4.0; Ronakshah1990, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Art historian Finbarr Flood has examined the complex motivations behind the re-use of stone at the Qutb mosque within a broad socio-political framework and has asked questions that go beyond the generally held view of religious iconoclasm (destruction of images). [3] Flood’s work has pointed to the probable use of spoliated (repurposed) stones from temples associated with the polities that were conquered by the Ghurid army (hence suggesting a political rather than religious motive), and has examined the important artistic interventions at the mosque (such as the meaning behind the addition of new stones that were carved to emulate temple pillars). [4]

Courtyard of the Qutb mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Daniel Villafruela, CC BY-SA 3.0). A c. 4th – 5th century iron pillar and the 12th century stone screen and prayer hall built by Qutb al-Din Aibak are seen here.

In 1198 Aibak commissioned a monumental sandstone screen with five pointed arches that was built between the courtyard and the prayer hall. The screen was constructed with corbeled arches and is emphatically decorative with bands of calligraphy, arabesques, and other motifs, including flowers and stems that pop over, under, and through the stylized letters (see below).

An arch in the screen (left) and a detail showing the calligraphy on the screen (right), Qutb mosque, screen begun c. 1198, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photos: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0; Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The prayer hall west of the screen has lost most of its components and the original mihrab (the niche that marks the direction of Mecca) no longer survives. Qutb mosque, c. 1192-3, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Ronakshah1990, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Iron pillar in the courtyard of the Qutb mosque, dated c. 4th—5th century C.E., Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Ranjith Siji, CC BY-SA 4.0)

An enduring legacy

In 1206, following the death of Muhammad Ghuri, Aibak declared himself ruler of the independent Mamluk (translated as “slave”) dynasty. Aibak’s efforts in building the Qutb mosque would endure longer than his tenure as sultan. Later rulers retained the mosque during expansions, indicating their reverence for the first mosque built in Delhi, and their regard for Aibak himself.

When Iltutmish became the new sultan of the Mamluk dynasty in 1211, he made Delhi the capital of the sultanate. During his reign, Iltutmish extended the screen and prayer hall on both sides of the west end of the Qutb mosque and added surrounding colonnades that, in effect, enclosed the original mosque. Iltutmish is also believed to have been responsible for the installation of the iron pillar in the mosque, a dhwaja stambha (ceremonial pillar) that dates to the fourth or fifth century and was originally installed in a Hindu temple.

The pillar has an inscription in the Sanskrit language that praises and eulogizes a ruler. In installing the pillar in the mosque and giving it pride of place, Iltutmish was following a tradition of previous rulers who appropriated such emblems of historic kingship to announce their legitimacy. In appropriating the pillar—and in effect the Qutb mosque as a whole—Iltutmish sought to affirm his political authority and legitimacy. [5]

Just as Iltutmish enclosed Aibak’s mosque with his additions, Ala al-Din Khalji, the ruler of the next Sultanate, would enclose the extension built by Iltutmish. Khalji had even grander plans, although his efforts were only partially realized (see annotated plan below).

Qutb Minar, begun c. 1192–3, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: lensnmatter, CC BY-2.0)

The Qutb Minar

In 1192–93, soon after conquering Delhi, Aibak also began work on the Qutb Minar, the impressive 238 foot tall minaret (tower) of red and light sandstone for his Ghurid overlord. The minar’s tapering, fluted, and angular bands contribute to the soaring affect of the monument. Its balconies are decorated with muqarna style (three-dimensional honeycomb forms) corbels that allow us to imagine the expansive views of Delhi from each of its five stories. The minar is decorated with bands of calligraphy that are both historic (referencing Muhammad Ghuri) and religious.

Detail of the Qutb Minar, begun c. 1192–3, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: juggadery, CC BY-2.0)

Construction on the minar had only reached the height of its first story at the time of Aibak’s death in 1210. The minar would be completed by Iltutmish and its great height and beauty would became emblematic of the power of the Delhi Sultanate.

Exterior view of Iltutmish’s tomb, c. 1236, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

An open-air tomb

Iltutmish’s tomb, which the namesake commissioned during his reign, is located in the northwest corner of the Qutb complex, outside of the mosque’s courtyard. Constructed from new stone (that is, not spolia), this square tomb is relatively simple in its exterior decorative program, but its interior stuns with its overwhelming ornament. Tall pointed arches frame arched doorways and niches, and calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran, floral ornament, arabesques, and geometric patterns adorn the walls.

Although it has been suggested that the tomb is missing its dome, its absence may have been intentional, allowing light to bathe the marble grave marker. Like the ornament that surrounds the tomb’s interior, this light directs our focus to the center of the monument, below which lies Iltutmish’s burial chamber.

Iltutmish’s tomb, c. 1236, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

Like the Qutb mosque and screen, Iltutmish’s tomb was built in the post and lintel fashion and its arches were corbeled. In contrast, less than a hundred years later, arches in Ala al-Din Khalji’s monuments were constructed with a keystone at its summit.

Domed gateways

Ala al-Din Khalji, a fourteenth century ruler who conducted many campaigns to subjugate rivals and to increase his wealth, had plans to expand the Qutb complex substantially. Although he was largely unsuccessful in realizing these ambitions, a ceremonial gateway attributed to his patronage is one of the site’s most important monuments. It is the only remaining monumental gateway of four that are believed to have been built along the perimeter walls of the complex.

Alai Darwaza, c. 1311, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Known as the Alai Darwaza, the gateway is a square structure built in 1311. Like Iltutmish’s tomb, the gateway is built from new stone. The tall red base, the alternation of white marble and red sandstone ornament, and the latticed windows lend substantial grandeur to the gateway.

The arches in the Alai Darwaza are in the form of horseshoe arches (literally an arch in the form of a horseshoe); the same form is used to also ornament the squinches, i.e., the transition (at the corners of the structure) from the square base to the octagonal ceiling that helps receive the dome. The dome rests on the arches and squinches, in the fashion commonly found in contemporaneous Islamic architecture outside of India.

Interior of the Alai Darwaza showing part of the dome, horseshoe-arch doorways, and the squinch (in the ceiling corner, above the latticed window), c. 1311, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

While building techniques changed from the corbeled arches of the Qutb mosque to the keystone-arches of the Alai Darwaza, there were also continuities. The use of Indic style architectural ornament (flowers, lotus buds, and bells), for example, remained an emphatic part of the sculptural vocabulary of Sultanate architecture.

Alai Minar

Ala al-Din also began construction of a minar that would have been considerably taller than the Qutb Minar, had it been completed—the unfinished base rises 80 feet in height. All that was built is the rubble core of the structure; the minar would have eventually been faced with stone, perhaps in a fashion and with adornment similar to that of the Qutb Minar.

Alai Minar, c. 1311, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Kavaiyan, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The early sultans of the Delhi Sultanate employed architecture as a tool to announce, maintain, and advance their identity as rulers. Much like older monuments were appropriated in the construction of the Qutb mosque, subsequent sultans appropriated the Sultanate’s earliest work to advance their claims to legitimacy.

The Qutb complex today

The Qutb complex of monuments is now a popular tourist destination, a transformation that can be traced back to the nineteenth century when the grounds were redesigned to appeal to English colonial visitors. The monuments were surrounded by neatly manicured lawns, roads were diverted for the exclusive use of visitors, and enclosures were built to fashion a tranquil setting. Although the Qutb complex has been changed throughout its history, the vision of its original builders remain plainly transparent.

Many thanks to Dr. Marta Becherini for her comments on this essay.

Notes:

[1] The five dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate were: Mamluk (1206–90), Khalji (1290–1320), Tughlaq (1320–1414), Sayyid (1414–51), and Lodi dynasties (1451–1526).

[2] These were Qutb al-Din Aibak (ruled 1206–10) and Shams al-Din Iltutmish (r. 1211–36) of the Mamluk Sultanate, and Ala al-Din (r. 1296–1316) of the Khalji Sultanate.

[3] Flood has shown that the inscription referencing the use of stone from 27 temples in the mosque’s entrance is anachronistic to Aibak’s reign; it is hence not considered here. See Finbarr Barry Flood, “Appropriation as Inscription: Making History in the First Friday Mosque of Delhi.” In Reuse value [electronic resource] : spolia and appropriation in art and architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine, edited by Richard Brilliant and Dale Kinney (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 121–47.

[4] See Flood’s Objects of translation: material culture and medieval “Hindu-Muslim” encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009); “Refiguring Iconoclasm in the early Indian mosque.” In Negating the Image: Case Studies in Iconoclasm, edited by Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 15–40; and “Appropriation as Inscription.”

[5] Flood, Objects, pp. 247–51.

Additional resources

Watch Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi, from UNESCO.

Catherine B. Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India before Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Aditi Chandra, “On Becoming a Monument: Landscaping, Views, and Tourists at the Qutb Complex,” in On the Becoming and Unbecoming of Monuments: Archaeology, Tourism and Delhi’s Islamic Architecture (1828-1963). University of Minnesota, 2011, pp. 16-70.

Finbarr Barry Flood, “Appropriation as Inscription: Making History in the First Friday Mosque of Delhi.” In Reuse value [electronic resource] : spolia and appropriation in art and architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine, edited by Richard Brilliant and Dale Kinney (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 121-47.

Finbarr Barry Flood, Objects of translation: material culture and medieval “Hindu-Muslim” encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Finbarr Barry Flood, “Refiguring Iconoclasm in the early Indian mosque.” In Negating the Image: Case Studies in Iconoclasm, edited by Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 15–40.

Street views:

Qutb mosque

Qutb Minar

View of Iltutmish’s tomb

Alai Darwaza

Alai Minar