What’s in a story?

In its simplest form, a story has a beginning, an end, and events that unfold in between. It has a cast of characters—protagonists we cheer and villains we don’t—and backdrops that supply the appropriate context, space, and mood for a story to unfold. Stories are dynamic and are transformed by the creativity and vision of storytellers.

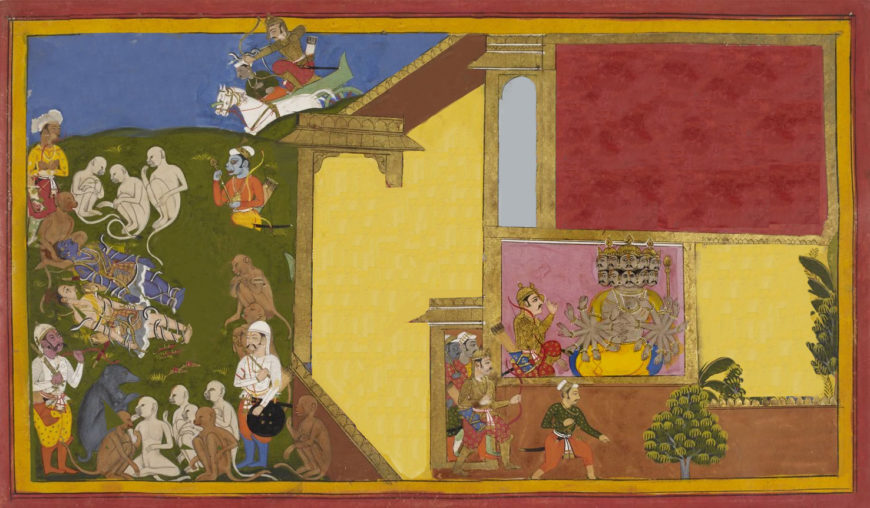

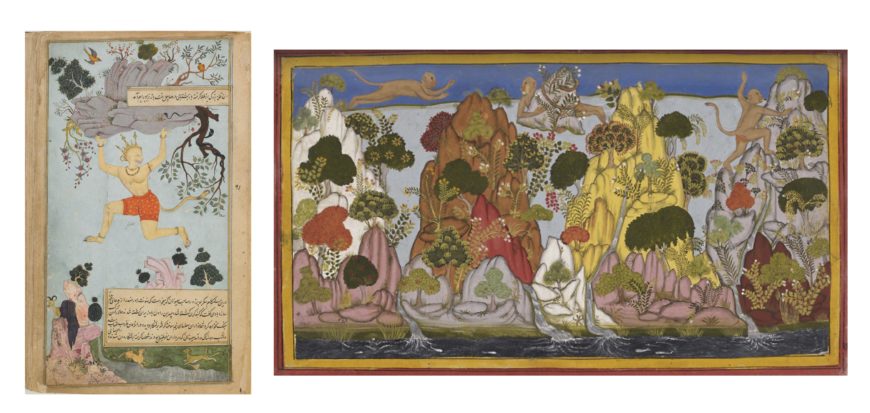

In the painted page below, the seventeenth-century master Sahib Din employed a range of colors, spatial devices, directional poses, and gestures to portray multiple events across multiple timelines. All of it is painted on a single horizontal page, only slightly larger than a sheet of typing paper.

“Indrajit meets with Ravana, then binds Rama and Laksmana with magic serpents; Sita is told they are dead,” folio from the Yuddha Kanda of the Ramayana, by Sahib Din, Udaipur, c. 1650-52, watercolor on paper, approximately 9 x 15.38 inches (British Library, Add. 15297(1), f.34 r)

The scenes portrayed in this page are a part of a much larger story, from the ancient Indian epic poem known as the Ramayana. The Ramayana was composed in Sanskrit between c. 200 B.C.E. and 200 C.E. The story centers on the confrontation of good and evil, and an exploration of the human condition. The principle characters experience love, loss, loyalty, conflict, fear, and friendship, all of which is underscored by a sense of dharmic or moral duty.

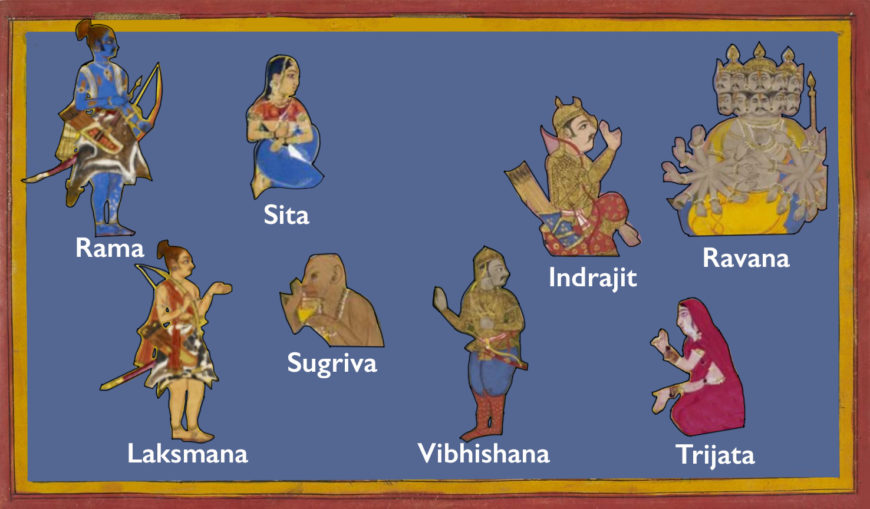

The hero of the Ramayana is the virtuous and benevolent prince Rama. Rama is accompanied by his loyal brother the prince Laksmana and many friends in a bid to rescue Rama’s wife Sita. Sita has been abducted by the demon king Ravana and is being held in the demon’s palace in the fabled kingdom of Lankapura. The Ramayana is an important text in Hinduism and Rama is held as one of the avatars of the god Vishnu.

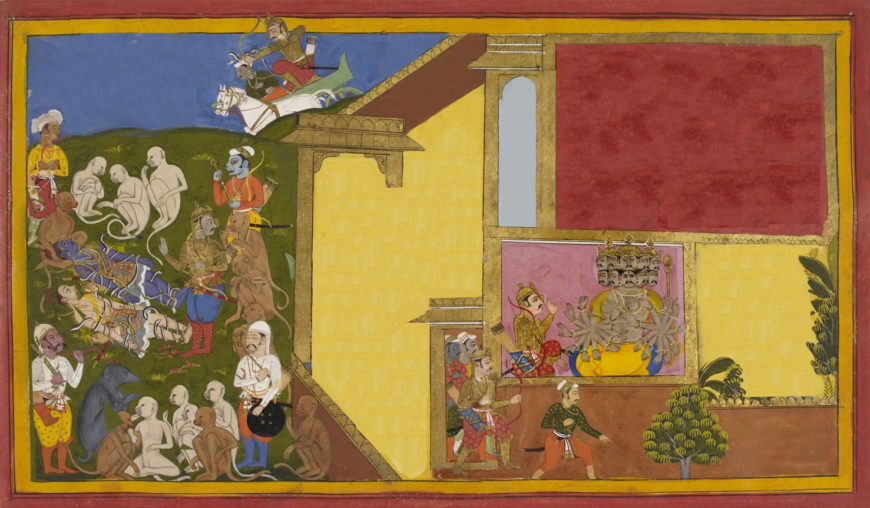

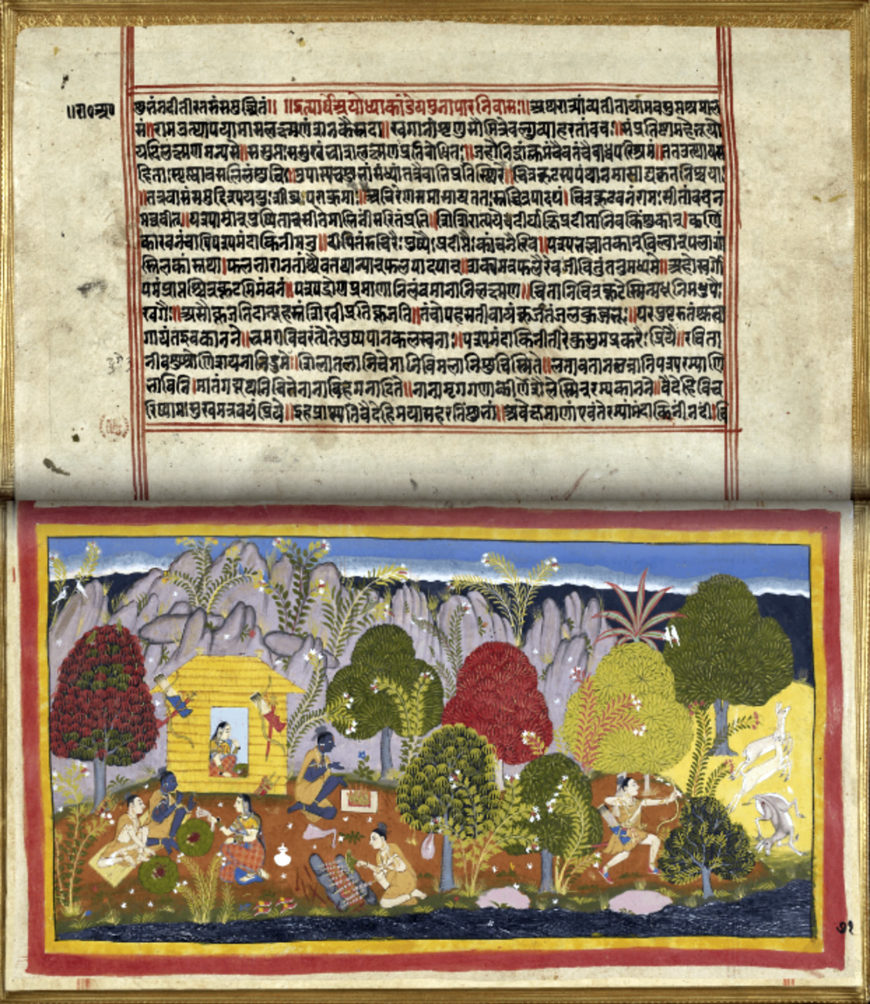

Sanskrit text and facing page showing Rama, Sita, and Laksmana living in exile, from the Ayodhya Kanda of the Ramayana, by Sahib Din, Udaipur, c. 1650-2, watercolor on paper, approximately 9 x 15.38 inches (British Library, Add. MS 15296(1) ff.70v and 71r).

According to tradition, the epic (which unfolds over multiple cantos) was composed by the legendary sage Valmiki. Scholars believe that in its earliest form, the Ramayana may have had as many as twenty thousand verses that were organized in five kanda (books). By the time the Mewar Ramayana manuscript was commissioned in c. 1650 C.E., the epic had grown to twenty-four thousand verses that were organized into seven thematic books centered on:

- Rama’s and Laksmana’s childhood and life in Ayodhya; Sita’s early life;

- Rama’s departure from Ayodhya and the start of his, Sita’s, and Laksmana’s life in exile;

- life in exile and the abduction of Sita by Ravana;

- adventures of Rama, Laksmana, and their allies;

- adventures of Rama’s friend and ally Hanuman;

- battles between Rama and Ravana’s armies and Rama’s eventual triumph; Sita’s return;

- Rama’s reign as king of Ayodhya.

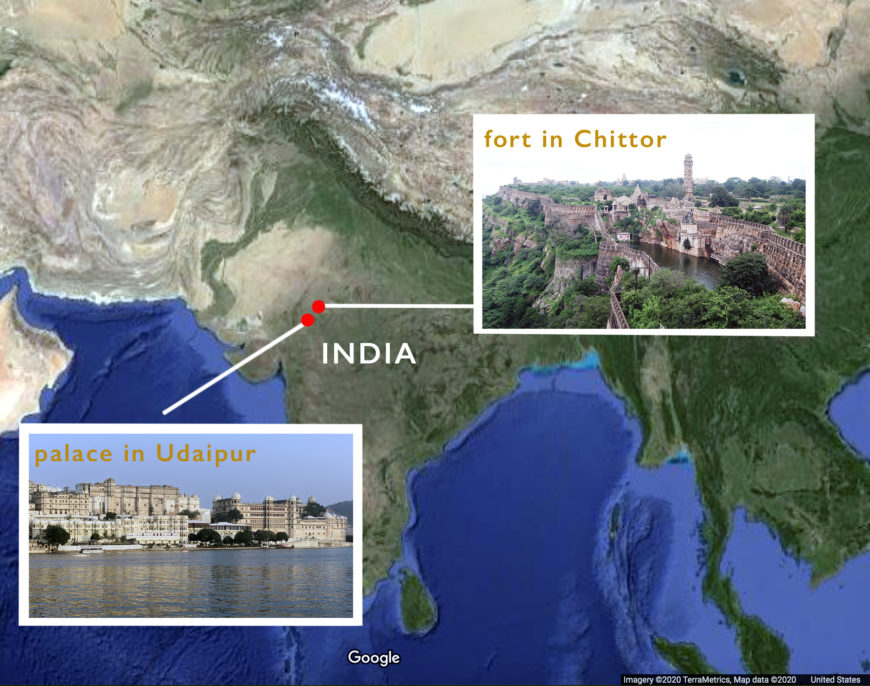

The Mewar Ramayana’s patron

The Mewar Ramayana is named for the royal Sesodiya Rajput court in the region of Mewar (in northwestern India) that commissioned it. The manuscript’s principal patron was the Maharana (Maha: great; rana: king) Jagat Singh, who ruled c. 1628–52. The rana’s investment in the production of the manuscript was immense—the illustrations in the Mewar Ramayana alone number four hundred. Scholars suggest that Rama’s identity as a righteous and powerful ruler in the poem would have been appealing to the royal patron Jagat Singh, particularly since his family, the Sesodiya Rajputs, claimed an ancestral connection to Rama.

A distinct Mewari style

Manuscripts produced in the Mewari imperial workshop were wrapped, unbound, in red cloth. A single scribe was responsible for all of the text in the Mewar Ramayana. However, at least three master artists and their respective workshops were selected to work on the seven volumes. An especially engaging artist, Sahib Din was responsible for all of the paintings in the the second and the sixth books, including the painted folio depicting “Indrajit meets with Ravana, then binds Rama and Laksmana with magic serpents; Sita is told they are dead” found in book six (see top of page) .

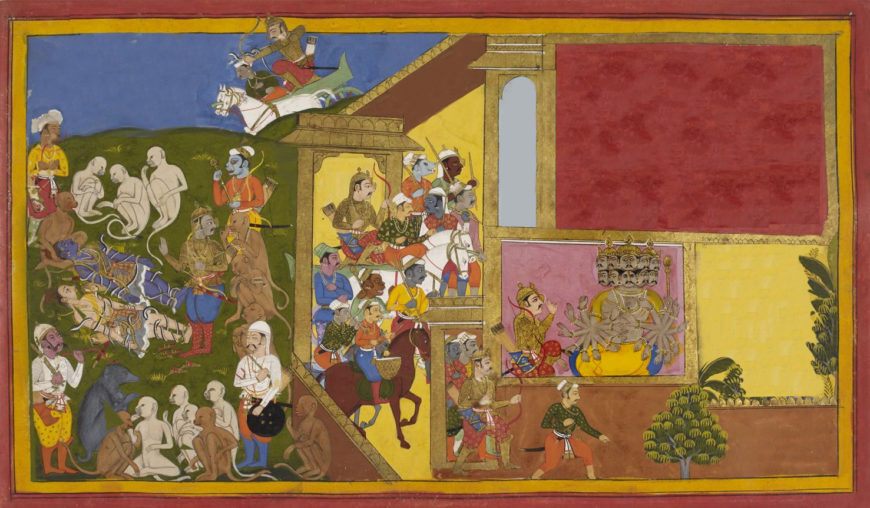

The Mewar ranas had become a vassal state of the Mughal empire—after decades of confrontation—during the reign of Jagat Singh’s grandfather Amar Singh in the early 17th century. The calm that resulted allowed contact and exchange between the courts. Even so, Mewar paintings remained distinct in style. This can be seen in the use of red and yellow borders, the use of bold deep colors, and the horizontal format which can be traced to the ancient custom of using palm leaves as a writing surface. The distinct style of Mewari paintings compared to those produced in the royal Mughal workshops can be seen by comparing a Mewari and a Mughal depiction of the same scene (images below).

Left: “Hanuman carrying a mountain of healing herbs,” folio from Mughal style Ramayana, late 16th century, 10-13/16 x 6 inches, ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper (National Museum of Asian Art); Right: “Hanuman goes to find the healing herbs, and returns with the mountain peak,” page from the Yuddha Kanda of the Ramayana, by Sahib Din, Udaipur, c. 1650-52, watercolor on paper, approximately 9 x 15.38 inches (The British Library, Add. 15297(1), f.100 r)

Mewari paintings rejected the vertical format, the relative naturalism in color, and the greater emphasis on depth found in Mughal paintings at this time. Mewari painters also depicted multiple episodes in a single scene, unlike the focus on a single event often found in Mughal paintings. Mewari techniques were also distinct. Where Mughal painters burnished each new layer of paint with a smooth stone, Mewari paintings were burnished just once after the painting was completed.

Mewari paintings more closely aligned with older regional painting traditions. A comparison between a painted folio completed more than a century before the Mewar Ramayana reveals similarities in the use of intense blocks of color as backgrounds, shallow foregrounds, and in the stylized portrayal of figures.

Left: “Krishna is Pampered by His Ladies,” Bhagavata Purana manuscript, c. 1520-40, North India (Delhi-Agra region), opaque watercolor and ink on paper, 6 7/8 x 9 3/16 inches (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); Right: “Indrajit meets with Ravana,” c. 1650-2.

Mewari manuscript paintings are especially ingenious in their portrayal of the passage of time and the representation of action. Art historian Vidya Dehejia has identified the “Indrajit meets with Ravana” page as an example of “complex synoptic portrayal.” In other words, the representation of multiple events within a single frame without a clear indication of the sequence of events. [1]

The artist, Sahib Din, used architectural features, bold colors, and manipulated perspective to structure distinct spaces that portray sequential events simultaneously. Even though the progression of events is not apparent, there is in fact a beginning, a middle and an end. The assumption is that the viewer is reading the matching text and has prior knowledge of the story. In this way, the images invite the viewer to unravel the painting’s narrative sequence.

“Indrajit meets with Ravana, then binds Rama and Laksmana with magic serpents; Sita is told they are dead,” folio from the Yuddha Kanda of the Ramayana, by Sahib Din, Udaipur, c. 1650-52, watercolor on paper, approximately 9 x 15.38 inches (British Library, Add. 15297(1), f.34 r)

Sahib Din tells the story

The painted page, “Indrajit meets with Ravana” (above) is from the sixth book known as the Yuddha Kanda, or the book of battles. Many of the pages of text in the book of battles are written on the reverse side of a painted page, although a few pages have text on both sides. The text and illustrations mostly stay on pace with one another. The page “Indrajit meets with Ravana,” portrays events from three cantos [2] and involves several protagonists. Almost all of these protagonists (shown below) appear more than once.

Principal characters in the “Indrajit meets with Ravana” folio. Figures of Rama and Laksmana (not by Sahib Din) taken from a page titled “Hanuman espies Rama and Laksmana as they approach Lake Pampa,” from the Kiskindha Kanda of the Ramayana, Mewar-Deccani style, Udaipur, 1653. British Library, Add.15297(1), f.2r. All other figures from the “Indrajit meets with Ravana” folio in the Yuddha Kanda.

Sahib Din chose to illustrate eleven moments in the principal narrative of this painting. The progression of events are each isolated below.

Scene 1:

the plan

The demon-king Ravana and his son Indrajit plan in private to defeat the prince Rama and his brother Laksmana. The multi-headed and multi-armed Ravana is much larger than his son Indrajit. Ravana is shown seated against a blue pillow, indicating his comfort within a palace represented by architectural features that structure the right side of the painting.

Scene 2:

Indrajit and his retinue leave the palace

Indrajit is recognizable among the figures walking through the doorway by the royal clothing he wears, a helmet, armor, and a bow and quiver of arrows. He has now appeared twice.

Scene 3:

Indrajit shoots magical arrows

A charioteer holds the reigns steady while Indrajit takes aim and shoots magical arrows at Rama and Laksmana. The arrows turn into snakes and the princes lie incapacitated while their allies are inconsolable. Because Indrajit’s actions were not seen, the artist has placed him at some distance behind a hill.

Scene 4:

Vibhishana assures Sugriva

In the fourth scene, Vibhishana—Ravana’s brother, an ally of Rama, and on the side of good—stands (wearing red boots) near Rama and Laksmana’s feet. He assures Sugriva—the deposed monkey king and an ally of Rama—that the brothers are unharmed. Sugriva is shown wearing a necklace of pearls (indicating his royalty) and listening to Vibhishana.

Scene 5:

Indrajit returns to the palace

Indrajit is shown a fourth time, but now at the center of the painting as he returns to the palace. His triumphant return is indicated by the crowd of figures, musical instruments, and the jubilant music they play.

Scenes 6 and 7:

Indrajit enters the throne room; Indrajit embraces Ravana

Scene 6: Indrajit enters his father’s quarters with his retinue. Ravana is again shown larger than his son. Indrajit and his soldiers report that Rama and Laksmana have been felled.

Scene 7: Father and son embrace over Indrajit’s success.

The same red background at the top right corner of the painting is used to indicate the throne room for scenes 6 and 7. Similarly, the figures of Ravana and the retinue are used for both scenes. Only the figure of Indrajit is repeated.

Scene 8:

Sita in the palace garden

Sita, Rama’s abducted wife, is shown seated in a garden within Ravana’s palace. She is surrounded by trees and has a finger to her mouth in a gesture of contemplation.

Scene 9:

The demoness Trijata misleads Sita

The demoness Trijata (an agent of Ravana) tells Sita that Rama and Laksmana have been killed. Trijata offers to take Sita to see for herself (indicated by the inclusion of the chariot behind them). Just as the throne room was reused in scenes six and seven, here the garden serves as the backdrop for scenes 8 and 9.

Scene 10:

The flying chariot

Trijata and Sita fly out of the palace on a golden chariot. Trijata sits in the front, as if leading the way.

Scene 11:

Trijata points to Rama and Laksmana

Trijata and Sita fly over the battlefield where Rama and Laksmana lie immobilized by the magical arrow-snakes. Trijata and Sita now face one another and the demoness points to the seemingly dead princes. Sita does not look, but is forlorn.

In the next illustrated page (not shown), Rama and Laksmana are freed when the magical snakes flee upon the arrival of the divine eagle Garuda.

Left and right, good and wicked

Sahib Din was careful to remain faithful to the details of the Ramayana, however incidental. Paradoxically, the artist’s evident knowledge of the story [3] enable his paintings to shine independently of the text that they are meant to illustrate.

The artist evokes from the reader an emotional investment in the characters he depicts. In addition to Sahib Din’s sensitive portrayals of Sita, the exchange between Vibhishana and Sugriva in scene four (in which Vibhishana assures Sugriva that Rama and Laksmana are still alive) conveys remarkable empathy. Sahib Din painted the eyes of Vibhishana and Sugriva in line with one another, expressing a shared moment of commiseration.

The composition of the painting reinforces the separation of heroes from villains. Rama and his army are placed on the left side; while Ravana and his kingdom Lankapura are placed on the right. This division of left (good) and right (wicked), follows the spatial organization that Sahib Din employs throughout most of the book of battles.

The artist also used this arrangement to portray multiple events within the same setting. The expansive backdrop on the left serves as the setting for Indrajit shooting magical arrows, Rama and Laksmana laying incapacitated, Vibhishana assuring Sugriva, and Trijata misleading Sita as they fly over the battlefield.

Map showing Mewar capitals of Chittor and Udaipur (photos: Ssjoshi111, CC BY-SA 3.0; Jakob Halun, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Mewar Ramayana as metaphor

While the battle between good and evil forms the arc of the Ramayana, the defining message of the epic is of Rama as a paragon of dharma. Rama sought to live his life sincerely as dharma requires—as a model son, brother, husband, prince, and king—no matter the personal consequences. Scholars believe that the Sesodiya Rajputs’ claim that they were the descendent of Rama in combination with the Maharana Jagat Singh’s considerable investment in the Mewar Ramayana indicates that the king sought to align himself with Rama as the perfect dharmic exemplar.

Vidya Dehejia has noted the timing of Jagat Singh’s commission of the Ramayana near the end of his reign, and the fact that it coincided with the rebuilding of Chittor, a Mewar fort that was destroyed during the protracted struggle between the Mughals and the Mewars. Although Jagat Singh’s grandfather Amar Singh had promised the Mughals (as part of the Mughal-Mewar treaty) that Chittor would never be rebuilt, Jagat Singh (based at the time in his capital of Udaipur) broke that promise and repaired the fort. Dehejia has suggested that the Mewar Ramayana might offer insight on the rana’s thinking at that time—perhaps he, like Rama, symbolized the good side, and Ravana and the Mughals stood to the right.