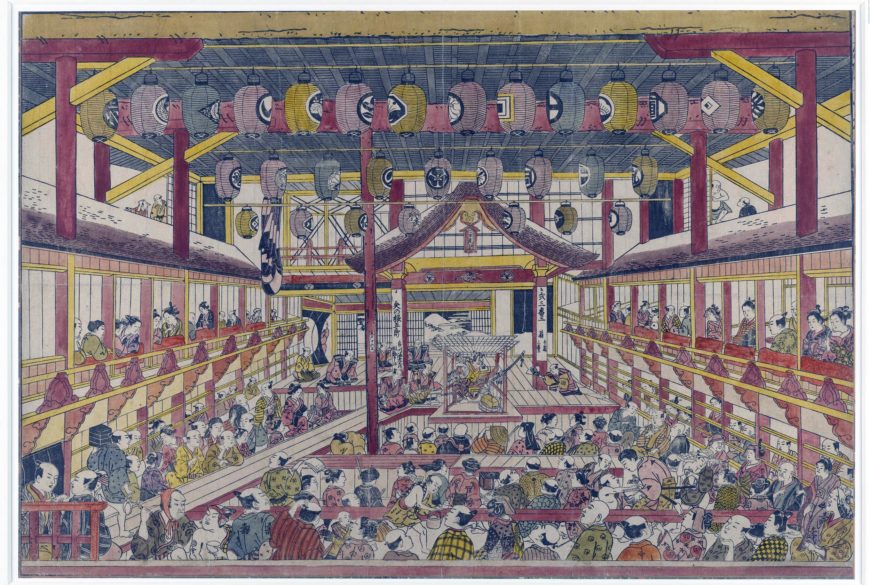

Okumura Masanobu (奥村政信), Interior of Nakamura-za theatre in Edo, with depiction of renowned actor Ichikawa Ebizo performing ‘Ya no ne Goro’ (Arrowhead Goro), 1745 (Edo Period), woodblock print with hand-colouring, uki-e, published by Okumura Genroku, Japan, 43.8 x 65 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Kabuki theatre developed from a popular entertainment performed by female dancers in Kyoto. This was banned in 1629 as detrimental to public morals, and replaced by young men’s Kabuki. From 1652 this was replaced by Kabuki performed by adult males. Although the government attempted to regulate Kabuki, the theatres, and their neighboring teahouses and houses of often homosexual assignation became thriving centers of urban culture, part of the ‘floating world’. The leading actors, including the onnagata, male performers of female roles, influenced fashion and taste and quickly became the subject of popular woodblock prints. It is likely that between one third and a half of prints published in the Edo period depicted Kabuki actors.

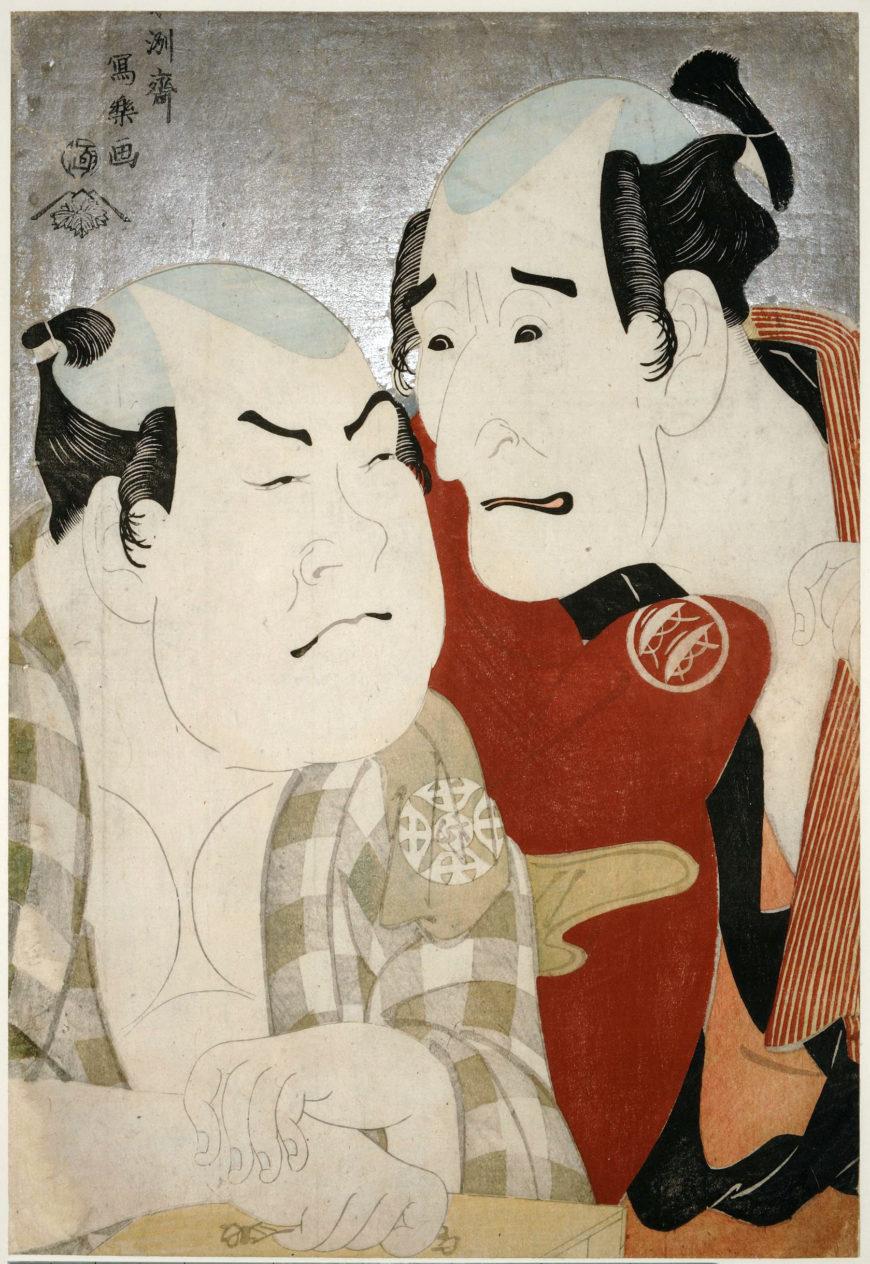

Three schools of artists specialized in designing actor prints. In the first half of the eighteenth century the Torii school was prominent. They started out using an exaggerated, muscular drawing style which captured the action of the animated aragoto (‘rough stuff’) style of the Kabuki. Later the Torii were eclipsed by the Katsukawa school. The founder, Shunshō and his contemporary Bunchō, were more restrained, and concentrated on capturing the likenesses of the actors (nigao-e). The Katsukawa school gave way to the Utagawa school (Toyokuni and Kunisada) from the 1790s onwards, and a return to a more florid schematic style. In addition, the enigmatic Tōshūsai Sharaku appeared briefly like a passing comet in 1794–95. In 1794 he produced a unique group of almost thirty highly individualized portraits in the ōkubi-e (‘big head’) format. These exaggerate the expressive quirks and gestures of the leading actors of his day.

It is often possible to date actor prints by referring to surviving printed banzuke (playbills) and yakusha hyōbanki (actor critiques). This is useful when studying the chronological development of an Ukiyo-e artist’s style.

Torii Kiyomasu I, The actors ōtani Hiroji and Ichikawa Danzō in an ‘armour-tugging’ (kusazuri-biki) scene, 1717 (Edo period), Edo (Tokyo), Japan, woodblock print, 68.7 x 51 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

‘Gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines’

The Kabuki ‘armor-tugging’ scene originated in the play about the revenge of the Soga brothers. It involved a struggle between the characters Soga no Gorō (right) and Kobayashi Asahina (left). However, it came to be inserted into other unrelated plays and in the summer of 1717 it was due to be performed ‘underwater’ in the play ‘The Battle of Coxinga’ (Kokusenya gassen), at the Ichimura Theatre. A large signboard was painted to hang outside the theatre, showing Hiroji bursting out through the side of the boat to grasp Danzō’s armor. In the event, the scene was cancelled, but the signboard painting, now lost, may well have been the inspiration for this print, since the Torii artists were responsible for producing all of the signboards, prints and illustrated programmes for the Kabuki theatres in Edo.

The characteristic acting style of Edo was known as aragoto (‘rough stuff’). The lively drawing style of the early Torii artists admirably catches the boisterous energy of the action. A later Japanese critic describes their figures as typically having ‘gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines’. The impact of this print is increased by the application by hand of orange lead pigment (tan).

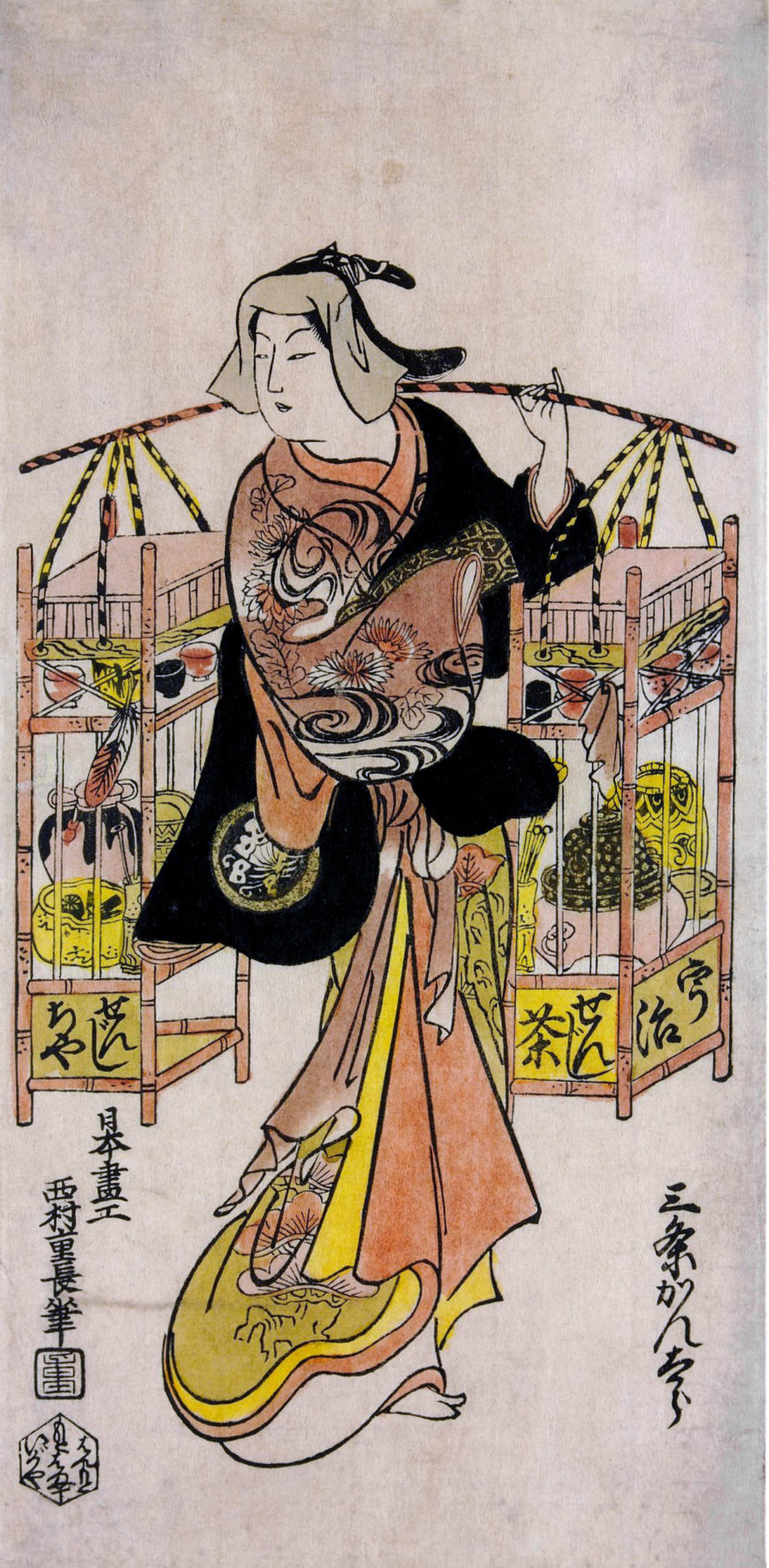

Nishimura Shigenaga, The actor Sanjō Kantarō as a tea-seller, c. 1716–36 (Edo period), Edo, Japan, a woodblock print, 32.8 x 15.9 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Female impersonators

The onnagata (female impersonator) Sanjō Kantarō plays the Kabuki role of a seller of Uji tea carrying her portable stall. The print is hand-colored in shades of red, pink and purple, all now somewhat faded. Glossy glue has been applied to the black over-kimono to give the effect of lacquer and there are sprinklings of brass dust on the obi sash, the butterfly crest on the sleeve and the lid of the kettle.

Kantarō has slipped off the right sleeve of the over-kimono to show off the elaborate under-kimono patterned with designs of waves and chrysanthemums. The overall elegance of the figure, especially the cocked little finger, suggests the he may be playing the role of some famous beauty in humble disguise. The tea implements are also drawn with great care, and we can see clearly all the details of the brazier and kettle with bamboo tea-scoop, tea jar, water pot and small cups.

Tōshūsai Sharaku, The Actors Nakamura Wadaemon and Nakamura Konozō, 1794 (Edo period), woodblock print, Japan, 35 x 24.2 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Large head portraits

The artist Tōshūsai Sharaku worked for a only a brief period, for ten months between 1794 and 1795. Very little is known of him before or after this period and his identity is the object of much conjecture among historians of Japanese art. The most likely theory is that he was one Saitō Jūrobei originally a nō actor in the service of the Lord of Awa.

Sharaku had a special talent for characterizing his subjects by differentiating their facial features. Furthermore, the development of the okubi-e (‘large head’ portraits) in the mid-1790s encouraged a more penetrating analysis of character. This print shows a scene from the play ‘A Medley of Tales of Revenge’ (Katakiuchi noriai-banashi) performed at the Kiri Theatre in the fifth month of 1794. The two subjects are strongly contrasted. On the right, Wadaemon in the role of Bodara no Chōzaemon, a customer visiting a house of pleasure, with his sharp, angular features, pleads with Kanagawaya Gon, the chubby boatman, played by Konozō. The boatman’s narrowed eyes and snub nose suggest that he is bent on striking a hard bargain.

Utagawa Kunimasa, The actor Ichikawa Ebizō in a shibaraku role, 1796 (Edo period), color woodblock print, Japan, 38.5 x 25 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

‘Wait a moment!’

Kunimasa (1773–1810) designed this print as a tribute to the great Ebizō (formerly Ichikawa Danjūrō V) on the occasion of his retirement from the Kabuki stage in 1796. He chose to depict him in the shibaraku scene, one of the most famous in all Kabuki drama. With a thundering cry of ‘shibaraku!‘ (‘wait a moment!’), the hero bursts on to the hanamichi walkway from the back of the theatre just in time to save the characters on stage from certain death. Perhaps, in this print, Ebizō is depicted on the very brink of calling out.

In this okubi-e (‘large-head portrait’), Kunimasa gives us an unusual profile view of Ebizō. The main elements of the striking costume and make-up are clearly visible: the ‘five-spoke wheel’ wig with, top right, the paper ‘strength’ decorations under the black lacquer court hat; the fierce red make-up; the green jacket with design of stylized cranes; and most significant of all, the familiar persimmon-colored costume with the three white interlocking squares (mimasu), which are the Ichikawa family emblem.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, A farewell surimono for Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII, 1849 (Edo period), Japan, color woodblock print, 27.2 x 55.5 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Tribute to a Kabuki actor

This print marks the occasion of the actor Danjūrō VIII’s temporary departure from the Edo stage in 1849 when he travelled to Osaka to visit his father, Danjūrō VII, who had been sent into exile there some seven years earlier under the severe Tempō Reforms.

To honor their idol, Danjūrō VIII, members of two haiku poetry clubs—the Shimba and the Uogashi clubs located in the fish market districts of Edo—banded together and commissioned the large de-luxe-edition print from Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). He chose as his subject a monster carp kite, appropriate to his sponsors and also to the time of year: Boys’ Day Festival is celebrated on the 5th day of the 5th month, when giant carp streamers are flown from poles. A carp ascending a waterfall was also one crest used by the Danjūrō lineage of actors. The design includes a cloth banner painted with a portrait of Shōki, ancient Chinese queller of demons. As a further tribute to the Danjūrō line, Shōki is given the features of the father, while the leaping carp, representing perseverance, may symbolize the son.

Danjūrō VII’s acting emblem was a curled lobster, and one of the poets, Taiwa, expresses the wish of all the fishmongers of the Nihombashi that he will return when he writes:

Nibune no

Ebi o machikeri

NihombashiNihombashi

Waiting for the lobster boat

To come to port

Danjūrō VII was indeed pardoned and returned to his adoring public in Edo later that year.

© The Trustees of the British Museum