Essay by Mei Mei Chan

The Southern Colossal Buddha Maitreya, Mogao Cave 96, 618–705 C.E., High to Late Tang dynasty, China (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Buddhism teaches that all the things surrounding us in life are impermanent. Love, money, happiness, pain, and even life itself are transient. According to some Buddhist schools of thought, even Buddhism itself is transient. Its current teachings will one day be forgotten, to be replaced by a new Buddhism.

The Buddha Maitreya is the Buddha of the Future. Technically, the Maitreya is not yet a buddha, but is currently a bodhisattva who resides and waits in the Tuṣita Heaven. The Tuṣita Heaven is one of the realms in Buddhist cosmology known for being a place where deities and bodhisattvas are born before they each enter their last human life cycle and achieve final enlightenment as buddhas.

Stele with Maitreya (in the “pensive” posture), 5th century, stone with traces of pigment Northern Wei Dynasty, China, 84.5 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

At any moment

A Chinese portrayal of the Bodhisattva Maitreya depicts him sitting in a posture with one leg draped over the other. This is known as the “pensive” posture.” Although many pensive bodhisattvas are commonly identified as Maitreya, this can be a hot topic of debate, depending on the image involved. If the bodhisattva represented is just a generic bodhisattva, then the descent to earth would be to aid the faithful who call on the bodhisattva for assistance. If the bodhisattva represented is Maitreya, the pose can indicate his imminent return to earth to establish a new age in Buddhism, or kalpa.

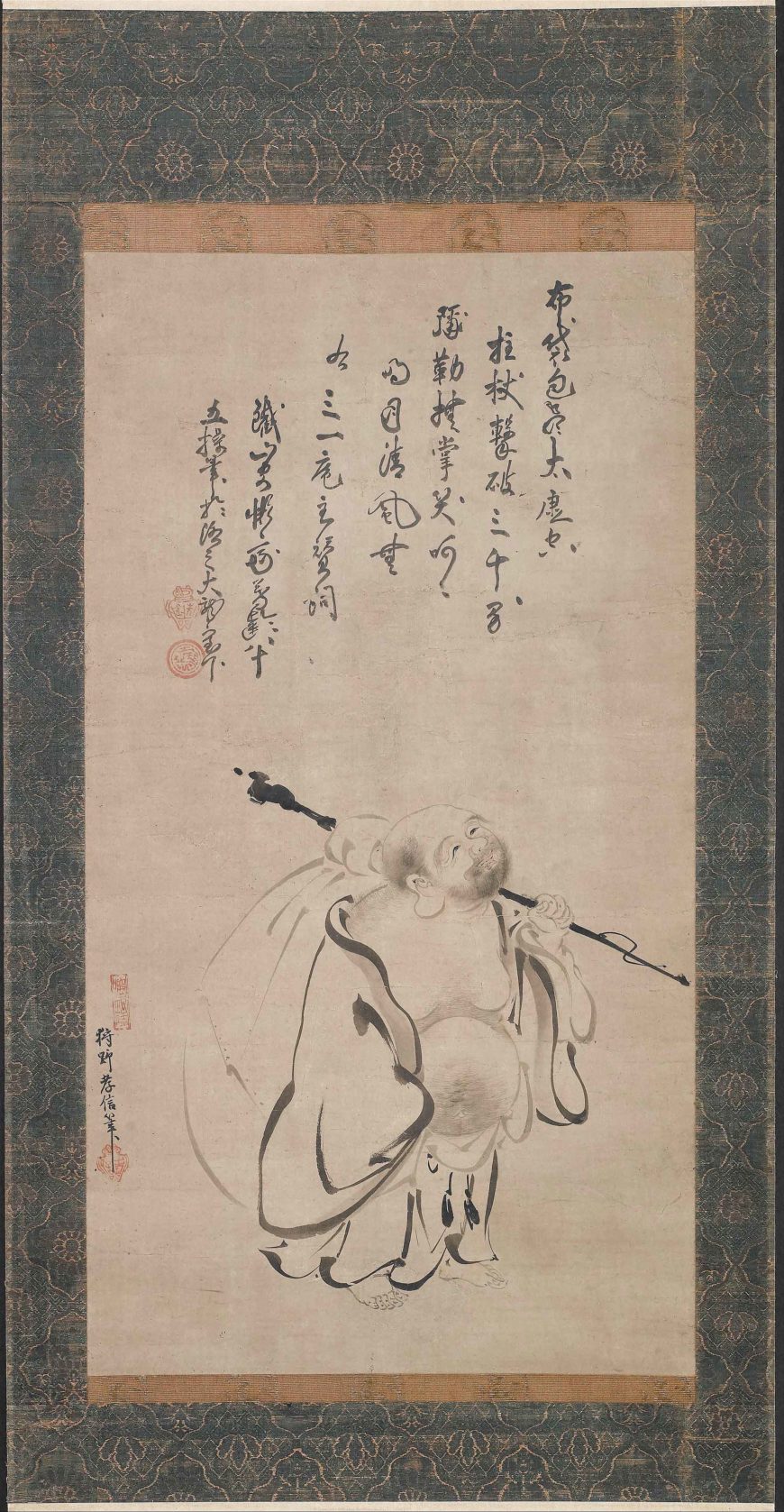

Kano Takanobu, Hotei, hanging scroll, 1616, Edo period, ink and color on paper, Japan, 69.9 x 38.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Laughing Buddha

Another popular representation of the Maitreya can be found in the images of the Laughing Buddha, or Budai (布袋, “cloth sack”), such as in a painting by Kano Takanobu. Also known as Hotei in Japanese, the round, good-humored monk is often identified as the Future Buddha. Hotei was probably a real historical figure who hailed from Zhejiang province in China.

A popular depiction of this incarnation of Maitreya is found in the final verse of the Ten Ox-Herding Verses. A young boy searches for his lost ox as a metaphor for seeking enlightenment. In the tenth and final verse, the young boy has found the ox and has returned home, and a portly stranger is suddenly introduced as the new central figure of the verse. Some readings interpret this older figure as the boy from the beginning of the poem:

He enters the city barefoot, with chest exposed;

Covered in dust and ashes, smiling broadly.

No need for the magic powers of the gods and immortals,

Just let the dead tree bloom again.Trans. Gen Sakamoto

Sanbo Zen Buddhist practitioner Kubota Jiun explains the depiction of Hotei as a laughing buddha in the visual representations of the tenth verse:

All pictures representing the tenth of the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures show a fellow named Hotei [ ?–917, Zen monk in old China]. He is said to have had a big belly. His gut is big and his chest bare. He has a big bag and a staff. And perhaps he has been walking barefooted. The attitude of the dear old Hotei, who is said to be a manifestation of Bodhisattva Maitreya, was presumably as that depicted by this verse. Kubota [Akira] Ji’un (1932–today), translated by J. Cusumano & Satō M.

The final line in the ox-herding verse may also allude to how billions of years in the future, Maitreya will usher in the rebirth of a new Buddhism following the complete passing of its current form.“Let the dead tree bloom again.” What was once old will become new again.

Wu Zeitan and Maitreya

A 17th-century Chinese depiction of Wu, from Empress Wu of the Zhou, 1690 (image in the public domain)

Beyond solely communicating Buddhist ideas, some artworks showing the Bodhisattva Maitreya had political overtones. For example, in the Tang Dynasty, Empress Wu Zetian (624–705 C.E.) used the narrative of the Bodhisattva Maitreya to further her political agenda. Empress Wu faced harsh criticisms as a female emperor, and many arguments against her were grounded in supernatural and spiritual reasons. When earthquakes or natural anomalies occurred, the court would seize the opportunity to declare that heaven and the earth were displeased by Empress Wu’s feminine energy. At the height of her power, Empress Wu declared herself the female incarnation of the Buddha Maitreya to assert her sovereignty. She called herself Emperor Shengshen (圣神), which translates to “Holy Spirit,” or “God.”

Statue of Vairocana Buddha, originally located in the grottoes of Longmen, carved in the likeness of Empress Wu Zetian during her reign (photo: Harlock81)

During Empress Wu’s reign, she commissioned large-scale Buddhist art such as statues of the Buddha carved in her own likeness. One such statue is the famous colossal Vairocana Buddha at the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, China. The Vairocana Buddha represents the “first buddha,” or the buddha from whom all other buddhas originate. The face of the Vairocana Buddha at the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang was modeled on the features of Wu Zetian.

Original essay on the Dunhuang Foundation blog.