Essay by Jang Sang-hoon

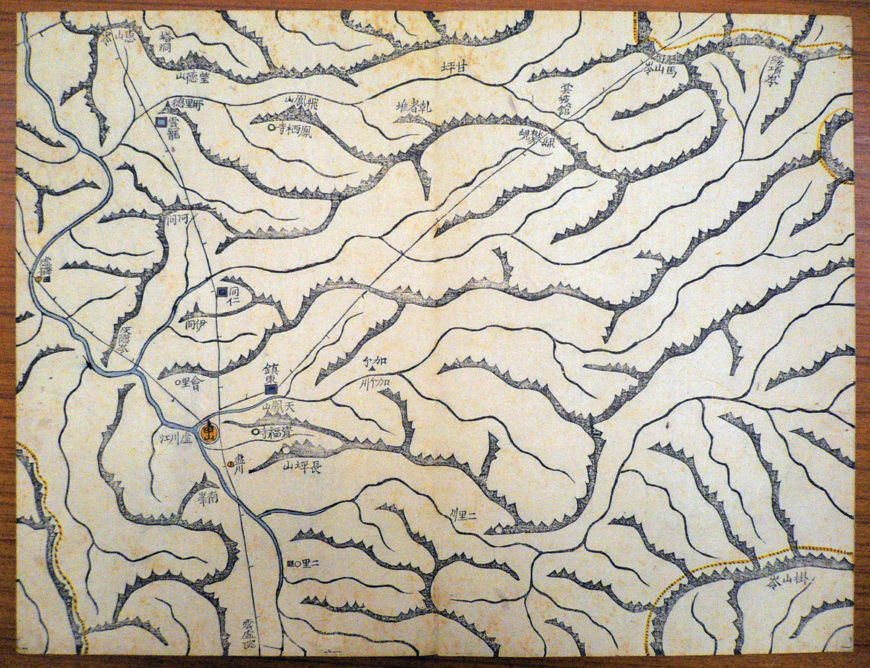

Detail of a woodblock showing the region of Mt. Jangbaek in Hamgyeong Province. Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East,” 大東輿地圖), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

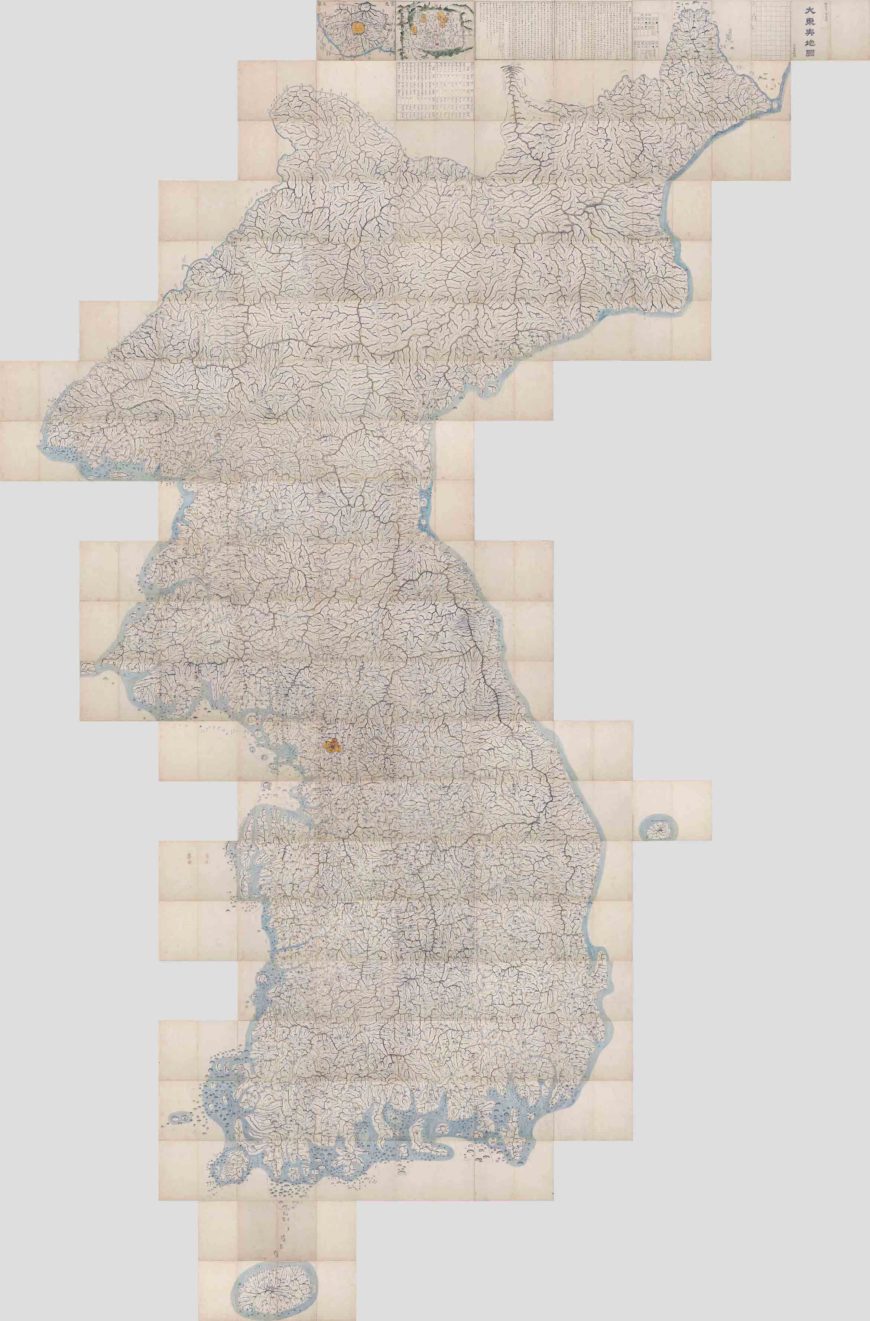

In 1861, the great cartographer Kim Jeongho produced the woodblocks and printed the map of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East,” 大東輿地圖). For this map, Kim Jeongho first divided the Korean peninsula into twenty-two equivalent sections from north to south, with each section measuring approximately 120-ri, or about 48 kilometers (1 ri equals approximately 0.4 kilometers). Each section was then made into one foldable volume of the map, with each page folding at a distance of 80-ri (approximately 32 kilometers). Thus, the entire territory of Korea was conveniently represented in twenty-two foldable volumes, much like a folding screen.

This image is a composite image of each map image stitched together. Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

By unfolding and aligning the twenty-two volumes, one could form a giant map of Korea, measuring 6.7 meters in height and 3.8 meters in width.

Detail of a woodblock showing the region of Mt. Jangbaek in Hamgyeong Province. Kim Jeongho emphasized mountain ranges as the frame of the country. Both the mountains and waterways are rendered in proportion to their respective size and significance. Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

In this map, Kim Jeongho described the Korean natural environment in great detail, emphasizing mountain ranges as the frame of the country. All of the nation’s mountains are shown to form a connected network linking to Mt. Baekdu. The mountains are elaborately rendered according to their size and significance, while the waterways flowing between the mountains are differently depicted depending on their flow and volume. In addition to natural features, the map also vividly represents many human settlements and constructions, such as towns and transportation routes. With a wealth of information related to administration, transportation, the military, and the economy, Daedongnyeojido provided viewers with a rich and varied knowledge of Korean geography.

Detail of a woodblock showing the region of Mt. Gap in Hamgyeong Province. Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

Detailed Information on Both Sides of Woodblocks

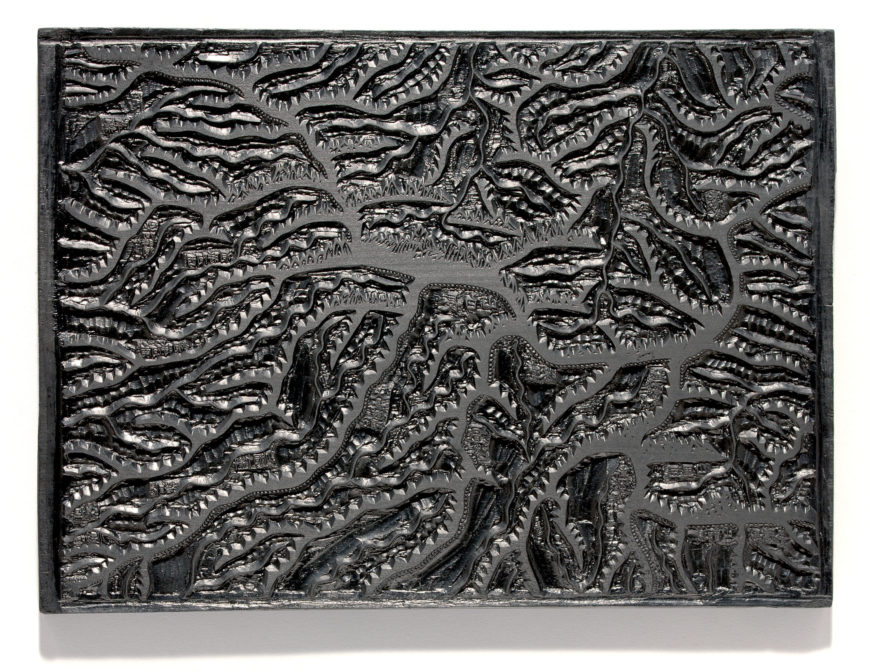

Beyond the vast geographical information that it conveys, this map is also an exceptional example of woodblock printing. All of the details of the map were meticulously carved into woodblocks, so that it could be easily printed many times and widely distributed. The decision to produce the maps with woodblocks was a stroke of genius intended to eliminate the flaws and mistakes that had plagued earlier maps, which were traditionally transcribed by hand.

The map is also notable for its use of symbols to represent about 11,500 places, making them easy to recognize and understand. While enhancing users’ ability to interpret the geographical information, this innovation also served a more practical purpose related to the woodblock printing technique, as the use of symbols minimized the number of Chinese characters that had to be carved. Much like contemporary cartographic symbols, Kim Jeongho’s symbols are conveniently listed in a legend for easy comprehension.

The original version of the map was printed with approximately sixty woodblocks, carved on both sides; today, only twelve of these woodblocks are extant. Amazingly, it is estimated that these woodblocks were personally carved by Kim Jeongho himself. According to Village Observations (里鄕見聞錄) by Yu Jaegeon, Kim Jeongho was an adept sculptor who carved the world map Jigudo (地球圖) into woodblocks, at the request of Choe Hangi. However, the extant woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido show relatively diverse sculpting techniques, suggesting that Kim Jeongho may have been aided by one or more assistants.

Detail of a woodblock showing the region of Mt. Gap in Hamgyeong Province. Both the mountains and waterways are rendered in proportion to their respective size and significance. Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

With some variations, each woodblock is approximately 43 cm in length, 32 cm in height, and 1.5 cm in width. Unlike most other woodblocks from this era, these blocks have no handle, and they are relatively thinner in size. They were carved from lime trees that were around 100 years old. Like most Joseon woodblocks used to print books, eleven of the twelve extant woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido are carved on both sides, with each side covering an area of approximately 120 ri (north-south) by 160 ri (east-west).

Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

The only extant woodblock that is not carved on both sides is the one used to print the title page of Daedongnyeojido. About half of the surface of that woodblock is carved with the title (大東輿地圖), the date of production (當宁十二年辛酉, the “Sinyu version,” referring to the year 1861), and the name of the producer (古山子校刊, “edited and printed by Kim Jeongho”). In fact, there is now a blank indentation that was formerly occupied by the five characters representing the date (十二年辛酉, “Sinyu version”). It is thought that these characters were removed in preparation for the printing of the revised “Gapja” version of the map, produced in 1864; for the reprinting, the blank space was likely filled with four new carved characters representing the new date (元年甲子, the “Gapja year”).

Interestingly, the back side of the woodblock containing the map of Hamheung in Hamgyeong Province is carved not with a map, but with a template used to print ruled paper for transcriptions. In addition to the template, this side of the block also includes a dotted line and a small shape resembling an island. The latter may have been a type of sketch, used for practice before the final carving. Like the front surface, bearing the map of Hamheung, the back surface is also saturated with black ink, confirming that it was actually used to print ruled paper for transcriptions.

In fact, researchers recently discovered that the ruled template from the back of this woodblock was actually used to transcribe certain pages of Daedong Jiji (Geography of the Great East, 大東地志), Kim Jeongho’s famed geography book. Researchers studying “Overview of Geography” (方輿總志, housed in the library of Korea University) from Volume 15 of Daedong Jiji identified traces of the aforementioned dotted line and the island shape on certain pages, confirming that those pages must have printed with the back side of the Hamheung woodblock.

Detail of a woodblock featuring carvings of Yongcheon (Pyeongan Province), Bukcheong (Hamgyeong Province), and Gyodong (Gyeonggi Province). To maximize space, the blank areas on some woodblocks were filled with carvings of non-adjacent regions. Woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), Kim Jeongho, 1861l Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

Maximizing Space by Utilizing Blank Areas

Some of the woodblocks used to produce Daedongnyeojido, such as those representing coastlines or islands, featured areas of water with no designated sites. Rather than simply leaving these areas blank, Kim Jeongho wisely “recycled” the space by carving portions of non-adjacent regions. For example, the blank area on one of the extant woodblocks is carved with separate maps of Myeongcheon and Dancheon in Hamgyeong Province. Another woodblock features three different maps, representing Yongcheon (Pyeongan Province), Bukcheong (Hamgyeong Province), and Gyodong (Gyeonggi Province). The woodblock depicting Dongnae (Gyeongsang Province) is also carved with Heuksando Island (Jeolla Province), while Imjado Island (Jeolla Province) was added to the woodblock depicting Ulsan (Gyeongsang Province). During the printing process, only the part of the woodblock representing the desired area would be coated with ink, enabling the woodblocks to be used to print two (or more) regions.

Along with these extant woodblocks, printed editions of Daedongnyeojido confirm that other woodblocks were also carved with multiple regions. For example, the map of the thirteenth section (from north to south) shows traces of Muido Island off the coast of Gangneung in the East Sea, even though Muido Island is actually located south of Ganghwado Island in the Yellow Sea. Thus, although the woodblocks for this section are no longer extant, we can estimate that Muido Island was carved onto the blank area of the woodblock representing the coast of Gangneung.

Revising Woodblocks for Accuracy

Striving to produce the most accurate maps, Kim Jeongho pioneered the use of woodblocks for easy publication and revision. The woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido show many traces where errors were corrected after the initial publication. Kim Jeongho (金正浩, c. 1804–c. 1866), woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido (“Territorial Map of the Great East”), 1861, Joseon Dynasty, 32.0 × 43.0cm, Treasure 1581 (National Museum of Korea)

The woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido show many traces of revisions where errors were corrected after the initial publication. In order to print updated versions of the map, it was necessary to make the corrections directly on the woodblocks. Various extant editions of the map confirm that revisions were made from the very first edition. The revisions include fixing typos and misspellings, adding omitted places, and correcting the details of various terrains, boundaries, and transportation routes.

In the original edition, for example, Aneon Station in Seongju, Gyeongsang Province was misplaced. Thus, on the woodblock for that area, the original carving of Aneon Station was cut away, and a newly carved representation of Aneon Station was placed in the correct location. This revision can be easily discerned on the extant woodblock, which has an empty place where the name of Aneon Station was originally carved and the new carving of Aneon Station in the proper place.

Another revision can be seen on the woodblock representing part of Hamgyeong Province. Early editions of the map misrepresented the border between Simmallyeong and Hwatongnyeong in Jangjin of Hamgyeong Province, so the inaccurate border was eventually cut away from the woodblock. In later editions of the map, this border was either omitted or corrected by hand.

Furthermore, early editions of the map failed to include Samhakjin in Chogye, Gyeongsang Province. Thus, a rectangular slot was carved into the woodblock and a small piece carved with the name “Samhakjin” was inserted. That piece has been lost, but the extant woodblock contains the vacant rectangular slot.

As such, these woodblocks of Daedongnyeojido embody not only the territorial representation of Korea in the late Joseon period, but also the blood, sweat, and tears of the master cartographer Kim Jeongho, who dedicated his life to recording and distributing accurate geographical information.