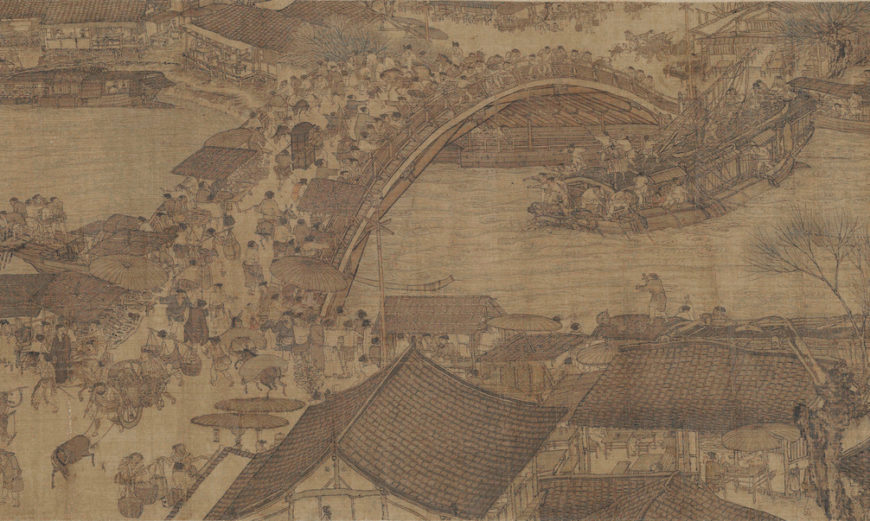

Rendered simply in tones of ink, Six Persimmons is a treasure of Zen Buddhist painting.

Six Persimmons, attributed to Muqi, 13th century (Song dynasty), ink on paper (Daitokuji Ryokoin Zen Temple, Kyoto). Speakers: Dr. Laura W. Allen, Senior curator for Japanese art, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco and Dr. Beth Harris

0:00:05.0 Dr. Beth Harris: I’m standing in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco in a very special exhibition that features just a single work of art that has never before left Japan.

0:00:17.7 Dr. Laura W. Allen: What we have here is a painting of six persimmons lined up in a perfect balance. Works by Muqi and those attributed to him, found a very enthusiastic and devoted audience in Japan after being introduced there by monks returning from studies in China. This painting belongs to Ryokoin which is a subtemple of Daitokuji, a Rinzai Zen temple in Kyoto. It’s been treasured in the temple for over 400 years.

0:00:44.6 Dr. Beth Harris: And persimmons, this juicy and sweet orange fruit. But here, no orange, only tones of grays and blacks.

0:00:54.6 Dr. Laura W. Allen: It’s really interesting to see how they’re rendered simply in tones of ink and very simple plain background. No table, no context, almost floating in space. It’s interesting because it’s one of the clues that tells us that it came from a hand scroll. That would be the way this kind of subject would be represented in a long hand scroll floating against a blank background.

0:01:16.6 Dr. Beth Harris: Those stems have such personality. They’re darker than the fruit and they’re made with a quick calligraphic feeling. And the persimmons on either end are indicated with the quickest of brushstrokes.

0:01:31.3 Dr. Laura W. Allen: A single brushstroke used to outline the two on either side of the composition. And then dark ink wash for the central persimmon and then tones of gray for the other three.

0:01:41.6 Dr. Beth Harris: It feels like we’re being asked to pay a lot of attention to things that we don’t normally pay attention to.

0:01:48.5 Dr. Laura W. Allen: The painting was hung in the tokonoma, the decorative alcove during tea gatherings. And one of the interesting things about this kind of painting is that it wasn’t meant to be hung on a permanent basis as a Western painting might be, or even as it is here in the museum for three weeks. But simply taken out for a few hours for a special occasion and then rolled up and put away for the next time. At the time when this painting entered the temple collection there was a preference for this type of rather simple ink painting or calligraphy as a choice for display in the tea room. The tea gatherings were an encounter between the host and a small number of visitors, could be as few as one visitor. And before the tea gathering occurred, they were very careful to select paintings that they thought would be suitable for a season, for a particular guest or occasion. And so we think that this painting, being seasonal for autumn, would have been used for during a fall tea gathering.

0:02:52.1 Dr. Beth Harris: Paintings by Muqi were highly sought after in Japan.

0:02:56.2 Dr. Laura W. Allen: They were and during the medieval period, the Ashikaga shoguns owned numerous paintings by or attributed to Muqi. I think over 100 are recorded in the records of that time. And within Japan, he became extremely influential. And we see the results of that in works by painters from many schools, particularly the Kano school, who were professional painters who served the shogunate.

0:03:20.9 Dr. Beth Harris: This painting and Japanese Zen painting generally started to gain popularity in the end of the 19th century but really took off in the early years of the 20th century.

0:03:30.1 Dr. Laura W. Allen: In the early 20th century, Zen Buddhism began to receive a great deal of attention outside Asia. Persimmons became a defining image for Zen. And it was featured in many different books about Zen and about the relationship between Zen and art.

0:03:46.5 Dr. Beth Harris: And it doesn’t really surprise me because at the early 20th century we have this appreciation for abstraction.

0:03:52.1 Dr. Laura W. Allen: I think that’s part of the reason they were so celebrated, especially after the Second World War. Earlier on, it really had to do with this perceived connection between the painting style and the level of spiritual awareness of the maker. And we kind of have moved away from that explanation as being too simplistic. We’re recognizing now that works like persimmons live side by side at Zen temples with myriad visual objects. There’s a huge mix of very colorful and very plain objects and objects with very specific religious subjects and more mundane subjects like these. So we now try to have a more nuanced understanding of the place of ink paintings like this one.

0:04:32.5 Dr. Beth Harris: One of the things that surprises me about this painting is how sometimes there’s little spaces between the fruit itself and those papery leaves.

0:04:42.5 Dr. Laura W. Allen: And the very wet brush that was used for those leaves is also remarkable in contrast to the very stiff and calligraphic strokes of the stems.

0:04:52.4 Dr. Beth Harris: There are places where it feels like the ink is pooling in the darkest fruit in the center, that draws our eye and gives a sense of stability to the composition. But other places where it seems the brush is drier, for example, in the line drawn on the outside of the persimmon on the far right, where we can even see the sense of the brush itself.

0:05:13.4 Dr. Laura W. Allen: And I think those variations between wet and dry brushstrokes, between dark and light, and the spacing of the persimmons, one to another, is what makes this painting so riveting. This painting is very enigmatic and open to interpretations. And that’s one thing that’s wonderful about it, that it has that open-ended quality. People will relate to it on a personal level.