Ban Chiang Jar, clay, Ban Chiang, north-eastern Thailand, 1st millennium B.C.E. (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The red on buff swirl designs found on Late Period (300 B.C.E.–200 C.E.) Ban Chiang vessels, like the one now housed in the British Museum, appealed to the aesthetic sensibilities of collectors. Hand painted, the bands of red that swirl every which way around the body of jars and pots, bely the steady hand of these ancient peoples and their culture of which we have no written documentation. In the decades since its discovery, archaeologists have pieced together a history for this prehistoric culture that is characterized by a peaceful Bronze Age society that was the first to develop wet-rice cultivation in the region of Southeast Asia.

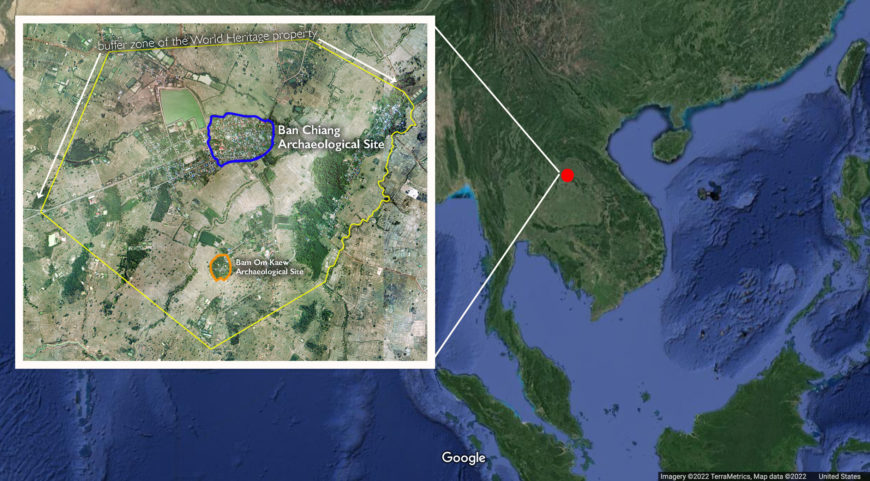

Map showing the location of the Ban Chiang Archaeological Site, province of Udon Thani, Thailand (adapted from a UNESCO map)

Ban Chiang, located in the northeastern Thai province of Udon Thani, is considered the most important prehistoric culture in Southeast Asia. Its significance is derived from over 300 excavated archaeological settlements that have unearthed a sophisticated material culture that includes painted ceramic pottery, metal tools, and jewelry, as well as the earliest evidence for farming in the region. The name “Ban Chiang” is not how the people associated with this culture referred to themselves. Instead, Ban Chiang refers to a modern village turned archaeological site where these prehistoric materials and human remains were discovered.

“Discovering” Ban Chiang

Although nearly all written histories identify Stephen Young as the first to discover this ancient culture in 1966, the villagers living there had known about artifacts related to it a decade earlier. [1] Moreover, the Fine Arts Department (FAD) of Thailand had listed Ban Chiang as an archaeological site in 1960. [2] While Young did not actually discover Ban Chiang, his political and cultural connections helped to create the right circumstances and elevate interest that made the excavations possible. In 1966, Young was a Harvard College student conducting field research for his senior thesis on Northern Thai village politics. His father, Kenneth Todd Young, Jr., had been an Ambassador to Thailand from 1961–63, and at the time of his studies was the President of the U.S.-based Asia Society. [3] During a walk in the village, he tripped on a tree root and fell over a partly buried ceramic pot, which he presented to his host Princess Chumbhot who alerted the FAD and her friend Elizabeth Lyons with the Ford Foundation in Bangkok. [4] One year later, excavations at the village commenced.

After the preliminary excavations took place, Lyons arranged for excavated ceramic sherds to be sent to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology for thermoluminescence (TL) testing. The results of the tests suggested that the sherds dated to 5,000–3,000 B.C.E. We now know that these dates are inaccurate because the TL technology—at the time—was still being refined. However, in 1971, the early dating created great excitement in the archaeological community since it suggested that Ban Chiang was the earliest Bronze Age site known. These dates have since been revised, with scholars now suggesting that the Ban Chiang culture dates from 2000 B.C.E.–300 C.E.

Reframing Southeast Asian history and culture

Adze, 300 B.C.E.–250 C.E., copper alloy, Ban Chiang Culture, Thailand (LACMA)

Even though Ban Chiang may not be the cradle of civilization, its discovery and study is significant to the history of Thailand specifically, and to the region of Southeast Asia more generally. Prior to its discovery, the region was seen as a cultural backwater whose major technological or artistic achievements were the result of Chinese and Indian influences. Until the discovery of Ban Chiang, archaeologists believed that bronze metallurgy was associated only with complex, socially stratified societies and that this technology was not introduced to Southeast Asia until 500 B.C.E. [5] Ban Chiang proved both hypotheses wrong.

First, metal objects found in burials at Ban Chiang date to the 900–300 B.C.E. and while the technology itself was likely introduced from southern China, this revised date is 400 years earlier than archaeologists had previously recognized. Second, burial remains at the excavation sites indicate that there was little social stratification during the Ban Chiang period; however, there is evidence that people had clear roles, such as farmers or hunters. This is quite surprising as the development of metal technology and use of metal tools and weapons is associated with social stratification and warfare, which is seen in other societies such as those from the Shang Period (1600–1050 B.C.E.) in China. Throughout its history, Ban Chiang appears to have been a largely non-hierarchical and peaceful society.

Bracelet with four bells, 300 B.C.E.–150 C.E., copper alloy, Ban Chiang Culture, Thailand (LACMA)

Also interesting is that metal jewelry such as bracelets and anklets are often found in the graves of children rather than adults, perhaps indicating their value in society. Small bracelets such as the one now in the collection of LACMA were crafted from molds utilizing an alloy of tin and copper. When new, this bracelet would have cast a golden hue.

Metal technology may have been introduced to the region from China; however, the production and craftsmanship of ceramic goods in Ban Chiang developed independently. During a joint excavation by the FAD and the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) in 1974 and 1975, an enormous number of ceramic sherds and vessels were unearthed. Ceramic vessels have been used to create a chronology for the Ban Chiang Period. This is possible because of the distinctive stylistic changes of the vessels over time and the documentation of their stratigraphic location during excavation.

Pot, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., black earthenware with incised decoration, 16.83 cm diameter, 12.86 cm high (LACMA)

Pot, Late Period, 300 B.C.E–200 C.E., fired and painted clay, Ban Chiang, Thailand (Penn Museum)

Early vessels, such as this flat bottom, black pot with corded design now at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, are distinctively different in style and form from later pots, which have thinner walls, and geometric red on buff designs. While we do not know if there was any meaning behind such painted designs, their appearance suggests that its makers and users had the time and interest in beautifying their wares. Although red on buff vessels have come to predominate our understanding of the Late Ban Chiang period, as collectors were drawn to this style, ceramic vessels continued to be made with a cord-marked design, utilizing fibrous materials such as rope, or incised with a stylus, likely made of wood.

Many of these vessels have been found in burials, but also as remains of daily life and include clues as to how these prehistoric peoples lived. In one such example, excavated pots from the joint FAD and UPenn excavations unearthed several vessels with rice grains and husks that were later examined. Studies concluded that Ban Chiang was the first culture to utilize wet-rice cultivation in the Southeast Asian region. This has been a point of pride for the modern Thai government and the nation’s people.

Celebrity and looting

After the incorrect initial TL test results, which associated Ban Chiang with the earliest Bronze Age, were made public in 1971, interest in Ban Chiang ceramic goods and metal objects increased exponentially and led to rampant looting. Collectors of such items included Thai cultural stakeholders such as Princess Chumbot and other social elites as well as American serviceman stationed at the US satellite Air Force base in Udon Thai. This helped to create a black market in illegally excavated wares and explains the prevalence and distribution of Ban Chiang artifacts in museums throughout the U.S. and elsewhere. The extent and speed of the looting threatened the ability to study the sites and better understand the prehistoric culture. In response, HM King Bhumibol Adulyadej enacted a law in 1972 that prohibited the sale or export of Ban Chiang artifacts. This, however, did not stop the continued looting or illicit market for Ban Chiang goods before the joint excavations in 1974–75, which was the first major excavations and systematic study of the sites. The excavations as well as advancements made in TL testing and carbon-14 dating resulted in a better understanding of the Ban Chiang settlements as well as a revision of the initial dates.

Open-air archaeological site of Wat Po Si Nai, with ceramic items visible, Ban Chiang Archaeological Site (photo: Ko Hon Chiu Vincent)

Interest in collecting Ban Chiang artifacts began a gradual decline after the revised dates for the period were published and made known to the public, and because the market had become diluted by forgeries made by enterprising villagers. This, however, has not diminished the importance of Ban Chiang in reframing our understanding of prehistoric Southeast Asia in the world, and the societies whose remains and material culture have given insight into this past. In 1992, the Ban Chiang Archaeological Site was recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage Site. Today, visitors can visit the Ban Chiang National Museum, which includes the open-air archaeological site of Wat Po Si Nai where one can see physical remains and ceramic items in situ. The museum also includes a building that exhibits antiquities unearthed from previous excavations.

Notes:

[1] Piset Charoenwongsa, “Ban Chiang in Retrospect: what the Expedition Means to Archaeologists and the Thai Public,” Expedition 24, issue 4 (1982): p. 13.

[2] Chester Gorman, “A Case History: Ban Chiang,” Art Research News 1, no. 2 (1981): p. 1.

[3] Stephen Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power; CORDS in the Villages of Vietnam 1967–1972 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), p. 365.

[4] Melody Rod-ari, “Who Owns Ban Chiang?: The Discovery, Collection and Repatriation of Chiang Artefacts,” in Returning Southeast Asia’s Past: Objects, Museums and Restitution, eds. Louise Tythacott and Panggah Ardiyansyah (National University of Singapore Press, 2020), p. 89.

[5] The significance of Ban Chiang from the Ban Chiang Project