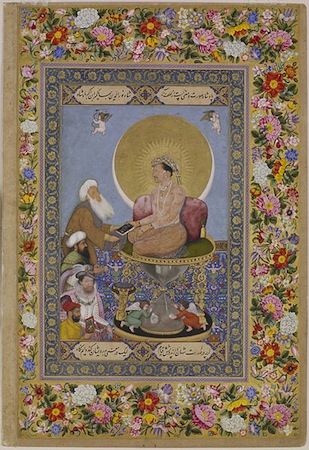

Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Seizer of the world

When Akbar, the third Emperor of the Mughal dynasty, had no living heir at age 28, he consulted with a Sufi (an Islamic mystic), Shaikh Salim, who assured him a son would come. Soon after, when a male child was born, he was named Salim. Upon his ascent to the throne in 1605, Prince Salim decided to give himself the honorific title of Nur ud-Din (“Light of Faith”) and the name Jahangir (“Seizer of the World”).

In this miniature painting, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, flames of gold radiate from the Emperor’s head against a background of a larger, darker gold disc. A slim crescent moon hugs most of the disc’s border, creating a harmonious fusion between the sun and the moon (thus, day and night), and symbolizing the ruler’s emperorship and divine truth.

Jahangir is shown seated on an elevated, stone-studded platform whose circular form mimics the disc above. The Emperor is the biggest of the five human figures painted, and the disc with his halo—a visual manifestation of his title of honor—is the largest object in this painting.

Emperor on a pedestal (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Jahangir favors a holy man over kings

Jahangir faces four bearded men of varying ethnicity, who stand in a receiving-line format on a blue carpet embellished with arabesque flower designs and fanciful beast motifs. Almost on par with the Emperor’s level stands the Sufi Shaikh, who accepts the gifted book, a hint of a smile brightening his face. By engaging directly only with the Shaikh, Jahangir is making a statement about his spiritual leanings. Inscriptions in the cartouches on the top and bottom margins of the folio reiterate the fact that the Emperor favors visitation with a holy man over an audience with kings.

From top to bottom, in order of importance, Ottoman Sultan, King James I of England, and the artist Bichitr (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Below the Shaikh, and thus, second in the hierarchical order of importance, stands an Ottoman Sultan. The unidentified leader, dressed in gold-embroidered green clothing and a turban tied in a style that distinguishes him as a foreigner, looks in the direction of the throne, his hands joined in respectful supplication.

The third standing figure awaiting a reception with the Emperor has been identified as King James I of England. By his European attire—plumed hat worn at a tilt; pink cloak; fitted shirt with lace ruff; and elaborate jewelry—he appears distinctive. His uniquely frontal posture and direct gaze also make him appear indecorous and perhaps even uneasy.

Last in line is Bichitr, the artist responsible for this miniature, shown wearing an understated yellow jama (robe) tied on his left, which indicates that he is a Hindu in service at the Mughal court—a reminder that artists who created Islamic art were not always Muslim.

This miniature folio was once a part of a muraqqa’, or album, which would typically have had alternating folios containing calligraphic text and painting. In all, six such albums are attributed to the rule of Jahangir and his heir, Shah Jahan. But the folios, which vary greatly in subject matter, have now been widely dispersed over collections across three continents.

During Mughal rule artists were singled out for their special talents—some for their detailed work in botanical paintings; others for naturalistic treatment of fauna; while some artists were lauded for their calligraphic skills. In recent scholarship, Bichitr’s reputation is strong in formal portraiture, and within this category, his superior rendering of hands.

Shaikh’s bare hands and the bejeweled hands of Jahangir (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Jahangir and the Shaikh

Clear to the observer is the stark contrast between Jahangir’s gem-studded wrist bracelets and finger rings and the Shaikh’s bare hands, the distinction between rich and poor, and the pursuit of material and spiritual endeavors. Less clear is the implied deference to the Emperor by the elderly Shaikh’s decision to accept the imperial gift not directly in his hands, but in his shawl (thereby avoiding physical contact with a royal personage, a cultural taboo). A similar principle is at work in the action of the Sultan who presses his palms together in a respectful gesture. By agreeing to adopt the manner of greeting of the foreign country in which he is a guest, the Ottoman leader exhibits both respect and humility.

King James I of England (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

King James

King James’ depiction is slightly more complex: Bichitr based his image of the English monarch on a portrait by John de Crtiz, which is believed to have been given to Jahangir by Sir Thomas Roe, the first English Ambassador to the Mughal court (this was a way to cement diplomatic relations and gifted items went both ways, east and west). In Bichitr’s miniature, only one of King James’s hands can be seen, and it is worth noting that it has been positioned close to—but not touching—the hilt of his weapon. Typically, at this time, portraits of European Kings depicted one hand of the monarch resting on his hip, and the other on his sword. Thus, we can speculate that Bichitr deliberately altered the positioning of the king’s hand to avoid an interpretation of a threat to his Emperor.

A self-portrait

Finally, the artist paints himself holding a red-bordered miniature painting as though it were a prized treasure. In this tiny painting-within-a-painting, Bichitr replicates his yellow jama (a man’s robe)—perhaps to clarify his identity—and places himself alongside two horses and an elephant, which may have been imperial gifts. He shows himself bowing in the direction of his Emperor in humble gratitude. To underscore his humility, Bichitr puts his signature on the stool over which the Emperor’s feet would have to step in order to take his seat.

Angel’s at Jahangir’s pedestal (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Putti and other (more mysterious) figures

Crying putto (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Beneath Jahangir’s seat, crouching angels write (in Persian), “O Shah, May the Span of Your Life be a Thousand Years,” at the base of a mighty hourglass that makes up the pedestal of Jahangir’s throne. This reading is a clear allusion to the passage of time, but the putti figures (borrowed from European iconography) suspended in mid-air toward the top of the painting provide few clues as to their purpose or meaning.

Facing away from the Emperor, the putto on the left holds a bow with a broken string and a bent arrow, while the one on the right covers his face with his hands. Does he shield his eyes from the Emperor’s radiance, as some scholars believe? Or as others suggest, is he crying because time is running out for the Emperor (as represented in the slipping sand in the hourglass)?

Kneeling figure at base of footstool (detail), Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615-1618, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 18 x 25.3 cm (Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art)

Also cryptic is the many-headed kneeling figure that forms the base of Jahangir’s footstool. Questions remain as to who these auxiliary figures are and what they or their actions represent.

Allegorical portraits were a popular painting genre among Jahangir’s court painters from 1615. To flatter their Emperor, Jahangir’s artists portrayed him in imagined victories over rivals and enemies or painted events reflecting imperial desire. Regardless of whether Jahangir actually met the Shaikh or was visited by a real Ottoman Sultan (King James I certainly did not visit the Mughal court), Bichitr has dutifully indulged his patron’s desire to be seen as powerful ruler (in a position of superiority to other kings), but with a spiritual bent. While doing so, the artist has also cleverly taken the opportunity to immortalize himself.

Additional resources:

This work at the Freer|Sackler

Commentary by Stuart Cary Welch on this miniature

High resolution image at the Google Art Project

Another image of Jahangir from the same album at the Freer|Sackler

Crill, Rosemary and Kapil Jariwala, eds. The Indian Portrait: 1580-1860 (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2010).

Guy, John and Jorrit Britschgi, The Wonder of the Age: Master Painters of India 1100-1900 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011).

Thomas Lawton and Thomas W Lenz, eds. Beyond the Legacy: Anniversary Acquisition for the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M Sackler Gallery (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1998).

Julian Raby, ed. Ideals of Beauty: Asian and American Art in the Freer and Sackler Galleries (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2010).

Sumathi Ramaswamy, “The Conceit of the Globe in Mughal Visual Practice,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 49 no. 4 (2007), pp. 751-782.

Seyller, John, “A Mughal Code of Connoisseurship,” Muqarnas, vol. 17 (2000), pp. 177-202.

Welch, Stuart Cary. India: Art and Culture 1300-1900 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985).

Wright, Elaine, ed. Muraqqa’: Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 2008).