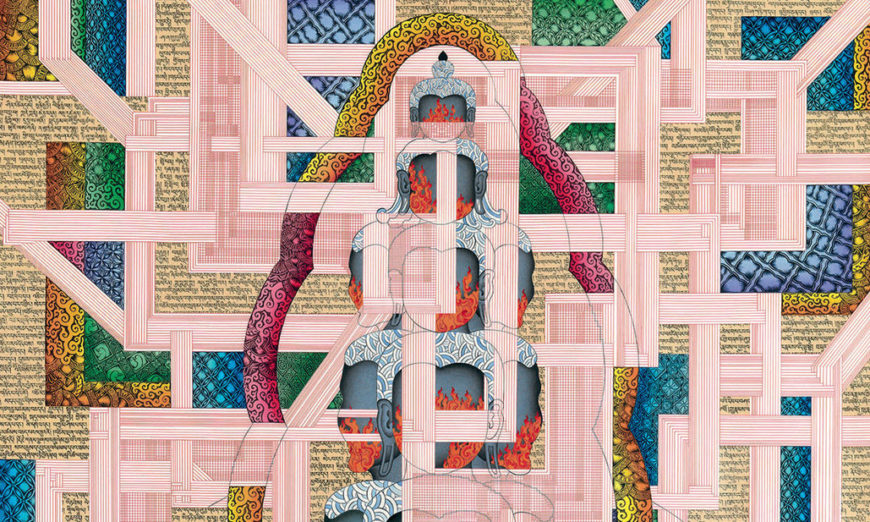

Each perfectly geometric, these mandalas are a graphic representation of the Buddhist conception of the cosmos.

Wangguli and five additional Newar artists, Four Mandalas of the Vajravali Cycle (Ewam Choden Monastery, Tsang Province, Central Tibet), 1429–56, pigments on cloth, 88.9 x 73.7 cm; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2007.6.1 (HAR 81826). Speakers: Dr. Karl Debreczeny, Senior Curator, Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art and Dr. Steven Zucker

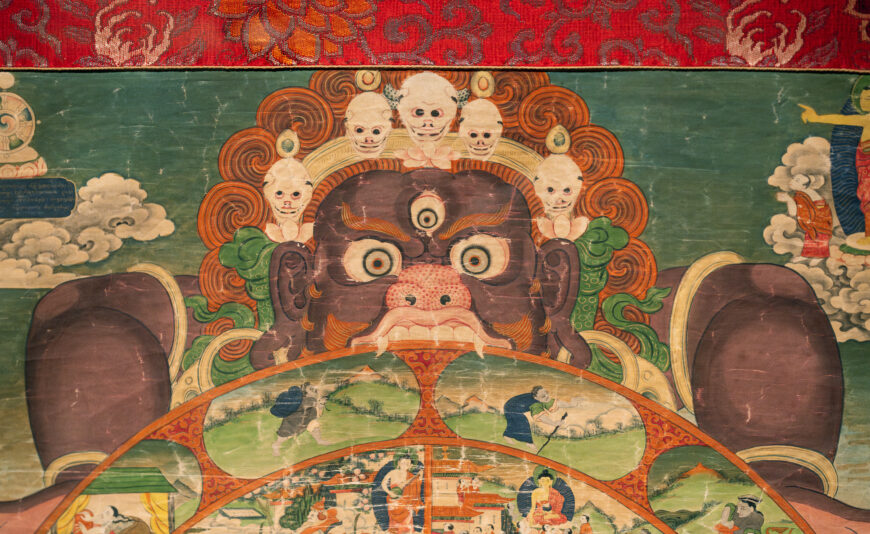

In Buddhism, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace. Mandalas are used by Buddhist practitioners for visualization during meditation. The Rubin’s Senior Curator Dr. Karl Debreczeny and Smarthistory’s Dr. Steven Zucker delve into one of the most important paintings in the Rubin’s collection, Four Mandalas of the Vajravali Cycle.

The Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art has teamed up with Smarthistory to bring you an “up-close” look at select objects from the Rubin’s preeminent collection of Himalayan art. Featuring conversations with senior curators and close-looking at art, this video series is an accessible introduction to the art and material culture of the Tibetan, Himalayan, and Inner Asian regions. Learn about the living traditions and art-making practices of the Himalayas from the past to today.