In an engraving from around 1600, a nude woman reclines on a hammock while a standing, dressed man approaches her. She is a personification of America, while he is Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine navigator who would give his name to the Americas. The scene, called “Discovery of America,” was first drawn by Netherlandish artist Johannes Stradanus in the 1580s. It was then transformed into a print series that formed part of Nova Reperta, or New Inventions and Discoveries of Modern Times (c. 1600). This scene is the most famous of that series, appearing first among twenty engraved plates.

Vespucci and a Personification of America

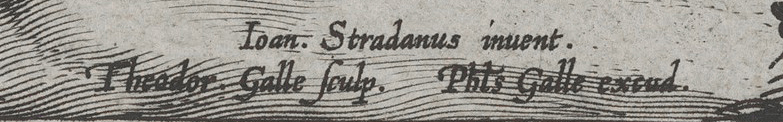

Theodoor Galle (after Johannes Stradanus) “The Discovery of America,” from Nova Reperta, c. 1600, engraving, published by Philips Galle, 27 x 20 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the print, as the original ink, Vespucci wears a cape over his armor. A sword hangs at his side. In one hand he holds a navigational instrument (an astrolabe) while in the other he holds a banner with a crucifix at the top. To his left are the ships he commands, one ashore and the other sailing towards the Brazilian coastline. His presence seems to wake or perhaps startle the woman. While she is nude, she does wear an array of accessories, including a feathered cap and loincloth, and metal anklets (likely made of gold). A weapon, perhaps a club, rests against a nearby tree.

Theodoor Galle (after Johannes Stradanus) “The Discovery of America,” detail of America, from Nova Reperta, c. 1600, engraving, published by Philips Galle, 27 x 20 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

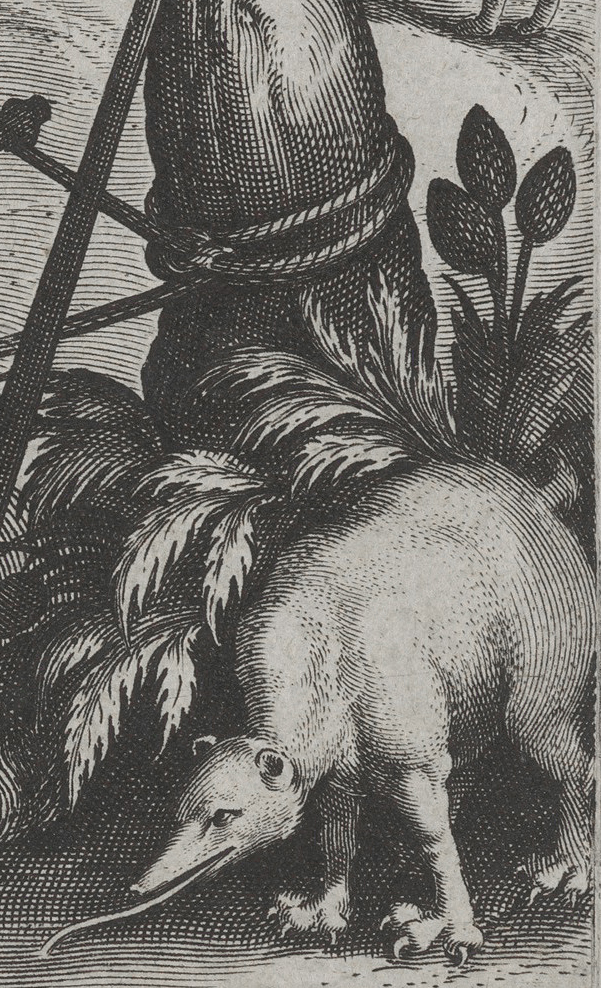

Theodoor Galle (after Johannes Stradanus) “The Discovery of America,” detail of anteater and pineapples, from Nova Reperta, c. 1600, engraving, published by Philips Galle, 27 x 20 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

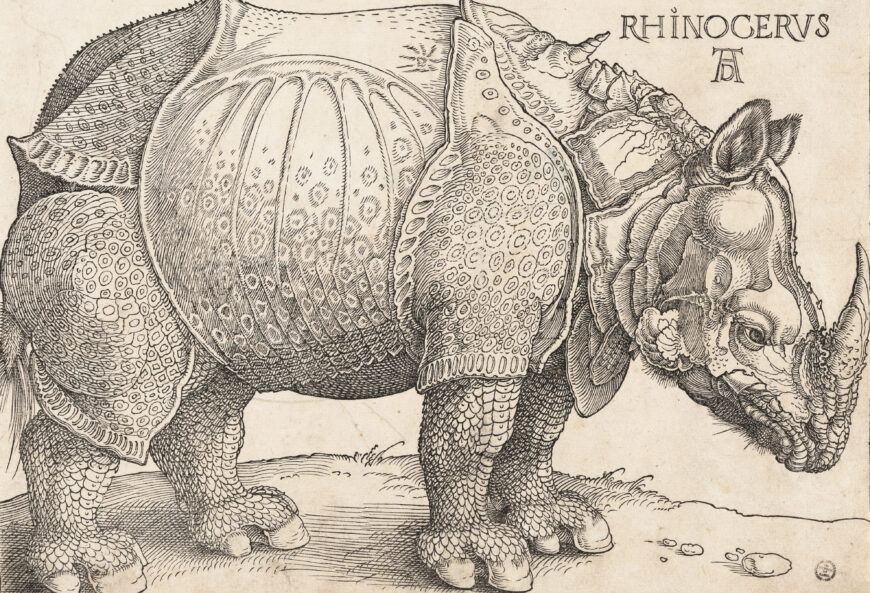

Surrounding her in the fore- and middle ground are animals, such as a sloth hanging from a tree, an anteater beside her club, and a tapir behind her shoulder, while in the background naked people roast human body parts over a fire. Pineapples grow on stalks just behind the anteater, appearing more like pinecones than fruit. It is clear that Stradanus never actually saw these plants or animals firsthand.

Stradanus contrasts the European and American figures and the worlds they signify. Vespucci is clothed, while America is not. He stands, she sits. He holds his banner upright, while her club is set aside. He comes from the sea, she comes from the land. His world has ships and navigational instruments, hers wild animals and cannibals. His body is obscured, while hers is available and sexualized.

These juxtapositions encourage viewers to make particular associations. Vespucci represents order and those that are civilized, while America symbolizes disorder and the uncivilized. His ships, sword, and astrolabe are also the instruments of exploration and conquest, used to subdue those people perceived as inferior. Stradanus portrays America and the cannibals behind her in the nude to underscore their primitive nature.

Who made this engraving?

An inscription is included that tells us who participated in making made the engraving. “Ioan. Stradanus inuent. / Theodor. Galle sculp. / Ph[i]l[ip]s Galle execud.” This means that Johannes Stradanus designed the image, Theodoor Galle engraved it, and Philips Galle distributed it.

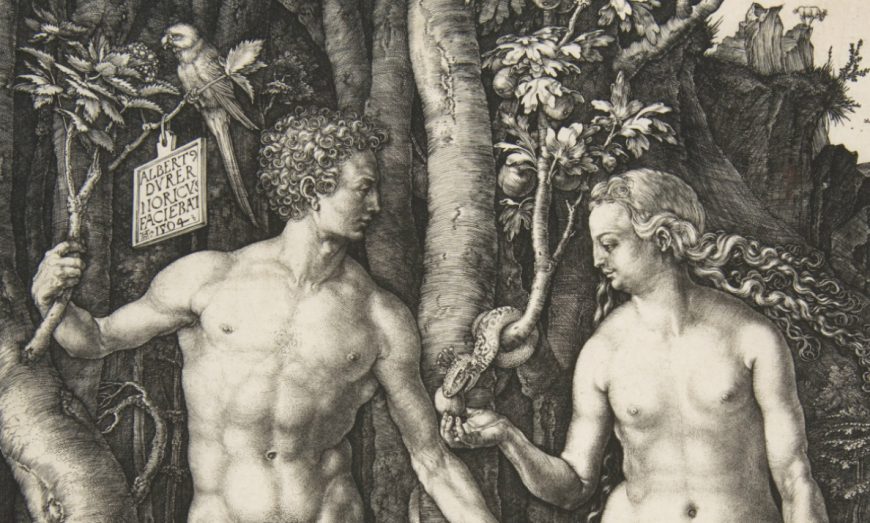

Stradanus, originally Jan van der Straet, was born in Bruges (now in Belgium), in 1523. He eventually moved to Florence where he died in 1605. More than eighty years after Vespucci’s Mundus Novus (New World) was first published in 1503, Stradanus produced his drawing, which was then engraved in Antwerp by Theodoor Galle at the workshop of Philips Galle. This collaborative practice was common among printmakers in the early modern period.

Stradanus and new inventions

Besides the “Discovery of America,” Stradanus illustrated a number of other inventions and discoveries that were then transformed into engravings for Nova Reperta. In one, called “Color Olivi” (“Oil Paint”), he included the famous netherlandish artist Jan van Eyck in his workshop, preparing and using oil paint. Other plates credit Europeans with inventing printing, the compass, and gunpowder (despite their having all come from China originally). We can understand these engravings as participating in a broader message tying together European colonization, invention, and superiority.

The inscriptions in the engraving of America also reference these same ideas. The title is written as “America,” and more Latin text that says “Americen Americus retexit, et Semel vocauit inde semper excitam.” The first part translates as “Americus rediscovers America,” implying that Amerigo Vespucci has discovered America with fresh eyes after Christopher Columbus, who believed he had found Asia.

The “new world”

Vespucci had originally explored the Americas in two separate voyages, between 1499 and 1501, and Mundus Novus included the correspondence he supposedly wrote with Lorenzo Pietro di Medici, his patron. This correspondence might have been somewhat fictionalized. Nevertheless, it was in these letters that Vespucci first refers to the Americas as mundus novus, or “new world,” one that was not part of Asia as Christopher Columbus had claimed. This name, “new world,” has, unfortunately, stuck, privileging the European viewpoint over that of the millions of Indigenous peoples who already lived on the American continents.

Inventing the “Indio” and “America”

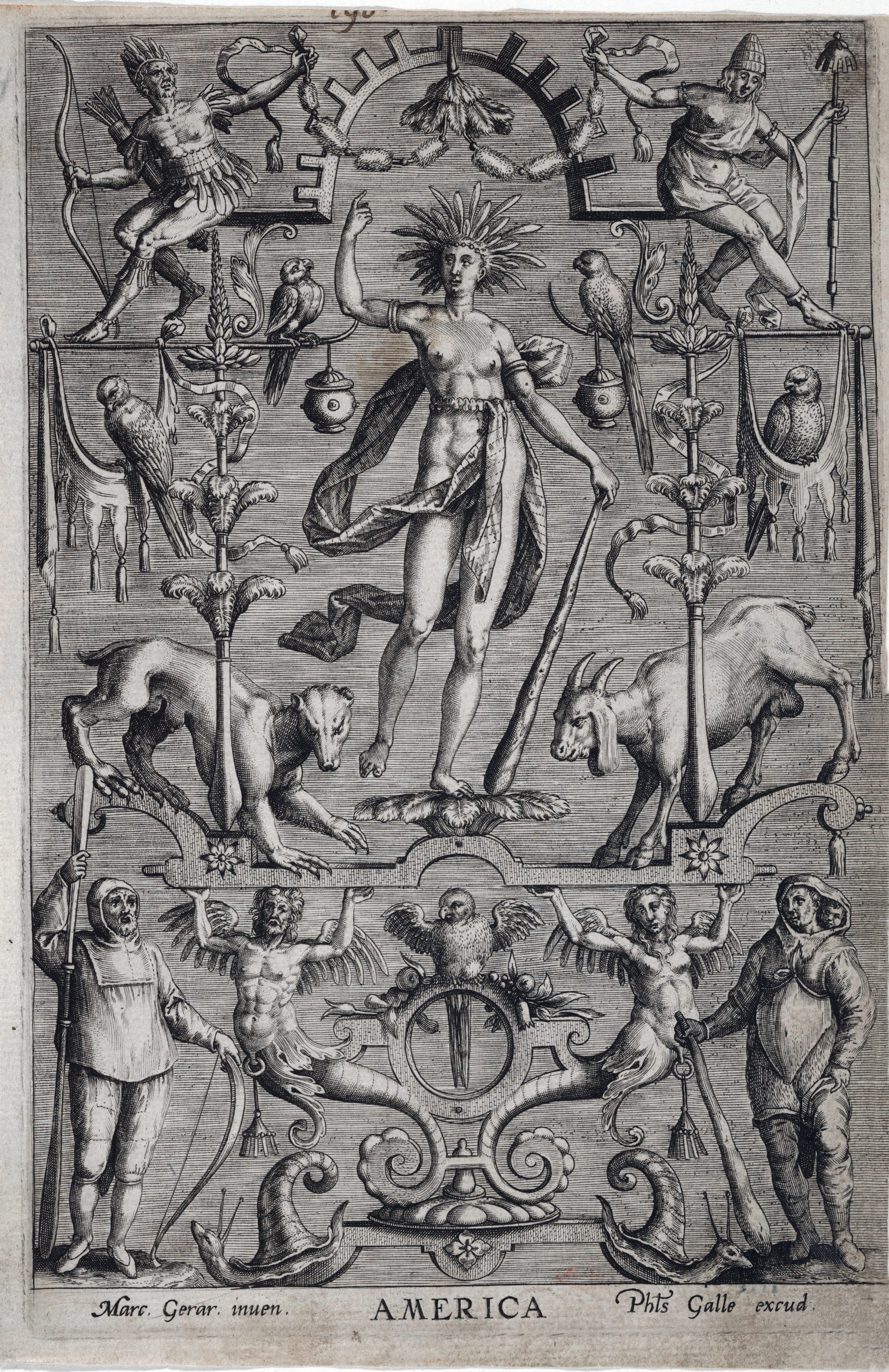

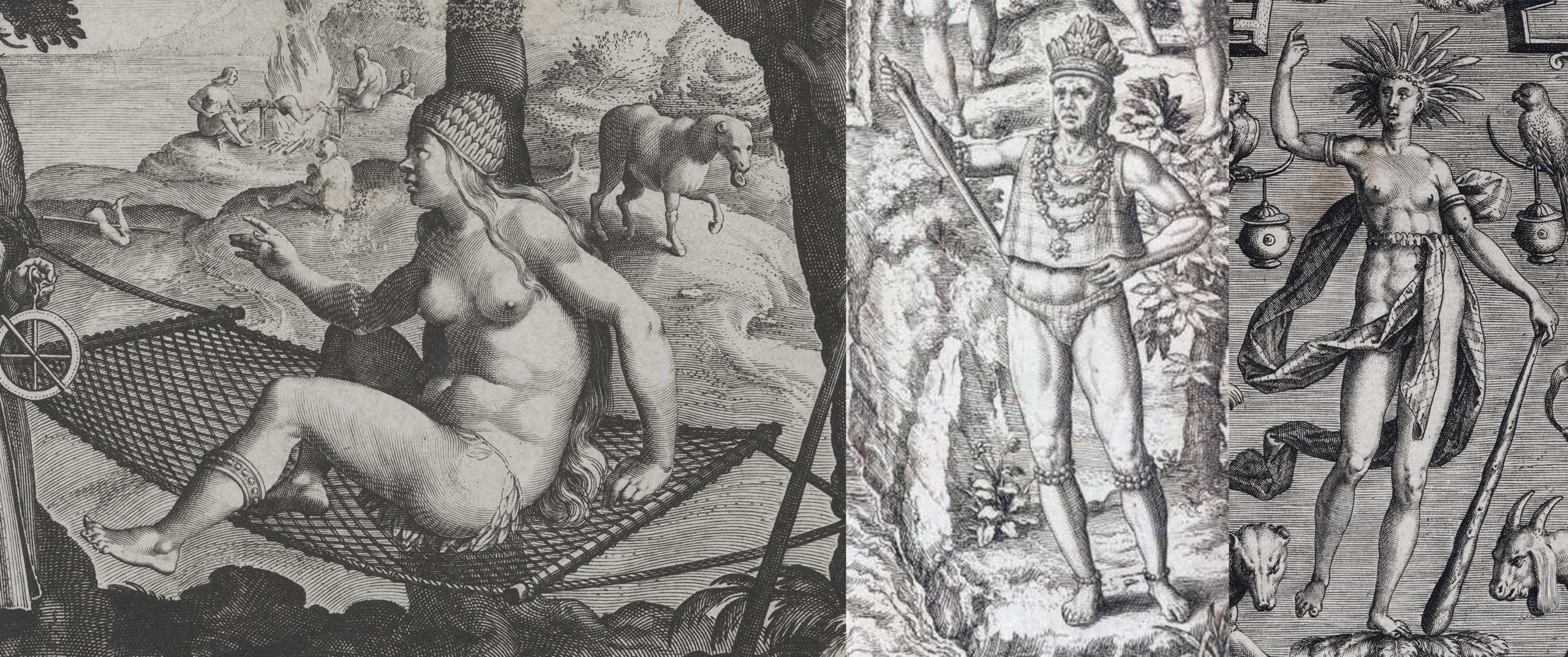

Images of “America.” Left: Theodoor Galle (after Johannes Stradanus) “The Discovery of America,” detail of America, from Nova Reperta, c. 1600, engraving, published by Philips Galle, 27 x 20 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Center: Theodor de Bry, Title page for “Historia del Mondo Nuovo,” title page (text by Girolamo Benzoni), engraving. Courtesy of the Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. Right: Marcus Gheeraerts (the elder), “America,” c. 1575–1610, engraving, published by Philips Galle (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When Christopher Columbus accidentally bumped into the Caribbean in 1492, he believed he had reached the Indies (India and Southeast Asia). As a result, the lands he encountered were named the ‘Indies’ and the peoples, indios. This misnomer of indio (Indian) wrongfully labeled the incredibly diverse groups of people not only of the Caribbean, but throughout all of what would come to be called the Americas. The name of indio aided in a process of homogenization of the peoples of this land. The term indio, at least early on, also served to differentiate those who were Christian from those who were not. Stradanus’s print participates in this homogenization. America is represented by a female personification, not specific individuals.

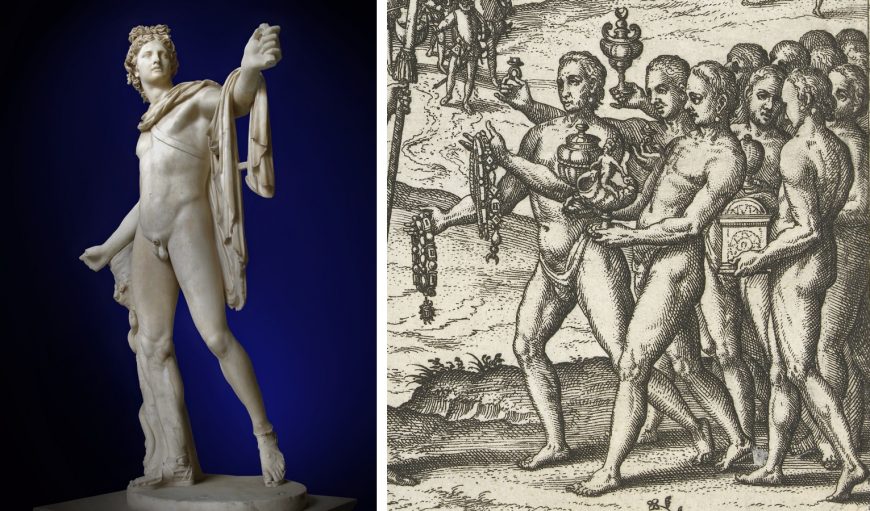

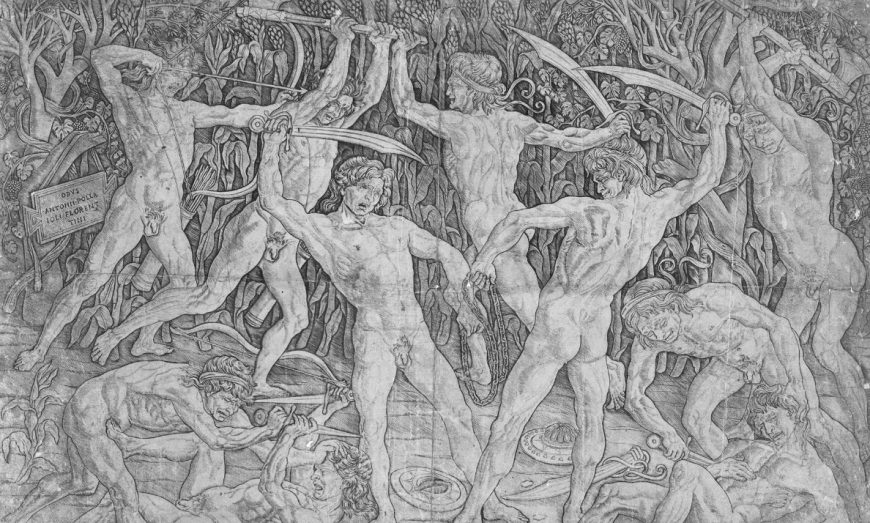

Earlier publications about the Americas had few illustrations, so printmakers like Stradanus felt free to invent imagery within their engravings and to borrow figures and motifs from other artists. We find many of the same visual motifs associated with America in prints by Stradanus and the artists Theodor de Bry and Marcus Gheeraerts (among others).

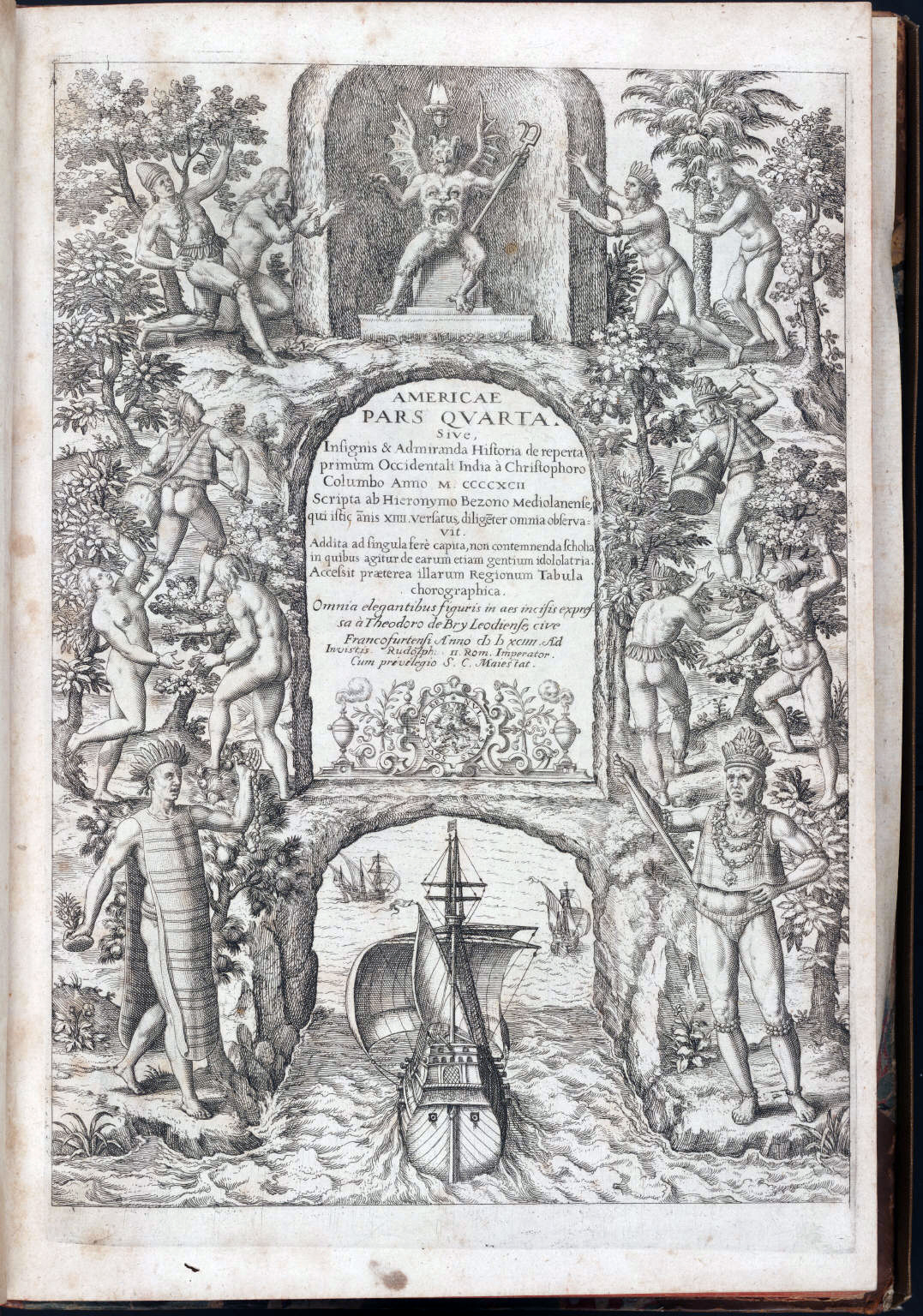

Theodor de Bry, Title page for “Historia del Mondo Nuovo,” title page (text by Girolamo Benzoni), engraving. Courtesy of the Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

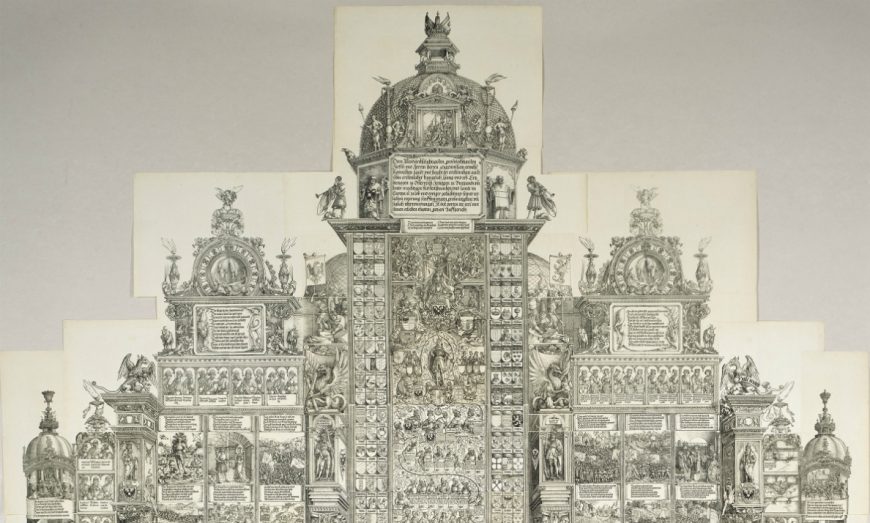

On the title page to volume four, called Americae, of his Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies, de Bry places the title in the center of a rounded-arch doorway. Above it, a demonic idol, complete with bat wings, mask-like face, and monstrous visage on its abdomen, sits on a throne. This purports to represent one of the deities of Amerindians. Below the title is a ship, sailing through a similarly shaped archway to join two other smaller ships. They represent the ships of Columbus, and we can read their passage through the arch as their departure from Europe as they embark on their voyage to the Americas. Flanking the center register are a variety of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, identifiable by what they do (or don’t) wear. Many of them are unclothed, while others wear simple loincloths and feathered headdresses. The two largest figures stand flanking the ships. One wears a long tunic and feathered headdress, while the other wears a crown, cropped tunic, large chains around his neck, and a loincloth. He holds a staff (or club) on his hip while standing in contrapposto. All the figures are idealized, with well-defined musculature that makes them look like Greco-Roman sculptures. We also find palm trees and other flora that help to locate the scenes in an American context.

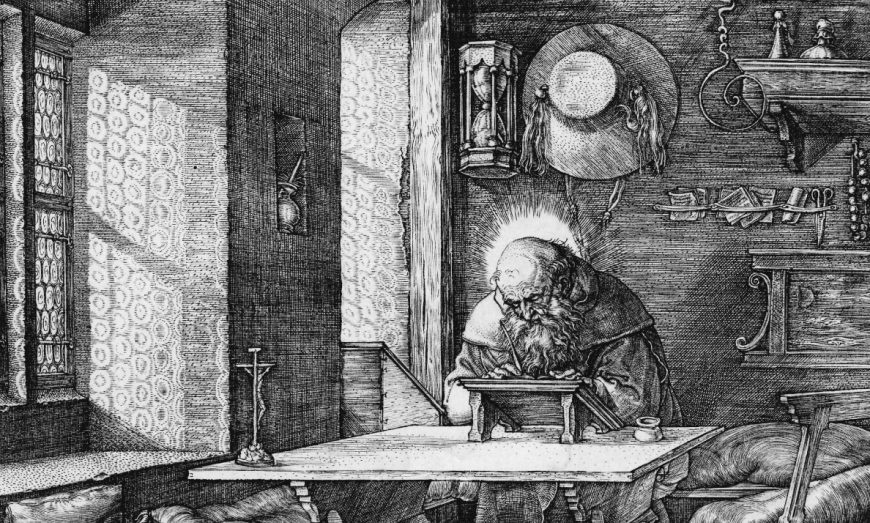

In Marcus Gheeraerts’s engraving of America, we see a barely dressed woman standing in contrapposto in the center of the composition. An elaborate feathered headdress rests on her head and she holds a club. Surrounding her are other be-feathered individuals, along with parrots, mammals like a tapir, two Inuits at the lower corners (based on drawings by John White), and even fantastical creatures–all of which draw from the same symbol set to portray the Americas.

As is clear from looking at these engravings, printed media played a crucial role in providing Europeans with information about the Americas in the early modern period. Stradanus’s print attests to the important role that iconography played in creating a defined set of symbols that would communicate to European viewers specific perceptions about America as exotic and primitive for centuries to come.