![Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks 春樹奇峰, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print from combined negatives. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 31. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui (from the Trans Asia Photography Review)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/tapic_7977573.0003.204-00000017_full_546_1200__0_default.jpg)

Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks 春樹奇峰, c. 1934, gelatin silver print from combined negatives (U-M Library Digital Collections, Trans-Asia Photography Review Images)

Photography in China

Photography arrived in China from Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, soon after the invention of the first photographic processes became publicly available. Around this time, the Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860) forced the Chinese imperial government to open trading ports to the West, including Shanghai and Canton. As trade developed along these port cities, Western diplomats, missionaries, and merchants brought the fashionable new medium of photography with them, along with the art of photographic portraiture.

Liang Shitai, Portrait of Li Hongzhang in Tianjin, 1878, albumen print, 29 x 22 cm (Lowentheil China Photography Collection)

Photography’s Indigenization

Almost as soon as photography was introduced, Chinese photographic entrepreneurs entered the field—first as portrait studio assistants and then as studio owners and even as photographers themselves. Working first with glass negatives, and eventually film, by the early twentieth century, Chinese photographers were already widely disseminating their own photography through magazines and journals.[1] Portraiture remained the most popular photographic genre.

Chinese photographers and their clients approached photography by adapting visual conventions and embellishments from painting such as inscribing their work with calligraphy using a Chinese brush. For example, Portrait of Li Hongzhang in Tianjin by Liang Shitai, includes a painted inscription and some inked retouching among the flowers. Such touch-ups were not necessarily to supplement or correct deficits in the image, but rather to adjust photographs to meet visual conventions. Popular motifs from traditional painting, such as plums, bamboo, and orchids, were added to photographic prints. All of these photographic manipulations suggest that artists actively adopted this foreign technology by imbuing it with characteristics of traditional Chinese painting.

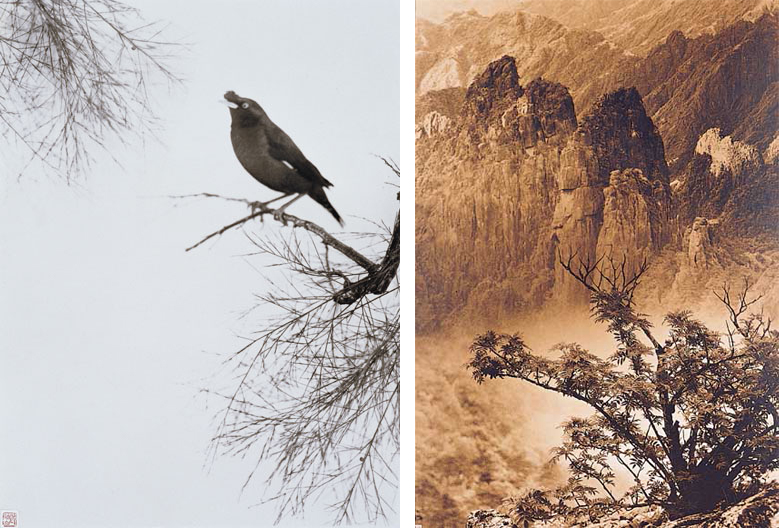

Left: Lang Jingshan, The Mynah, 1930, 35 x 27 cm, gelatin silver print (Taipei Fine Arts Museum); right: Lang Jingshan, Spring Trees, 1934, 90 x 62 cm, gelatin silver print (Taipei Fine Arts Museum)

Lang Jingshan

It was in the early Republican Era (1912–1949) that Chinese fine-art photography (photography created as a form of artistic expression) emerged, and Lang Jingshan was one of its early innovators. As a teenager studying in Shanghai, Lang received training in Chinese painting, but when his art teacher introduced him to the camera, he promptly fell in love with photography instead. Eventually, he became a central figure in the growing circle of serious amateur photographers in Shanghai. In 1928, Lang helped established the Chinese Society of Photography, a group of amateur photographers who promoted Chinese fine-art photography. His passion was art photography, but to pay the bills he also worked for newspapers and magazines, covering news and events, and shooting fashion spreads and advertisements. He even worked as photojournalist and war photographer during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.[2]

Composite Photography

With his broad photographic know-how, in the early 1930s, Lang developed his signature style of photography, which he called “composite photography.” In this specific style of fine-art photography, Lang utilized combination-printing and other darkroom methods to assemble photographic fragments into seamless compositions of his own creation. Lang describes composite photography as a kind of technical solution to the problem of photographing in the style of Chinese painting:

The difficulty, in photography, of producing an ideal and beautiful scene is two-fold. It depends on what the lens can take in, and it is limited by the disadvantages of machinery. . . . With composite pictures, photographers can now do just the same as the Chinese artists; they now have their choice among natural objects; they may now make their own compositions in photography. Neither time nor space need hereafter be an obstacle.[3]

A modern innovator, Lang Jingshan devised this photographic approach so that photographers could create their own compositions in much the same way as Chinese painters do.

Left: Lang Jingshan, Riverside Spring, 1934, 43 x 35 cm, gelatin silver print (Taipei Fine Arts Museum); right: Guo Xi, Early Spring, 1072, hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk, 158.3 x 108.1 cm (National Palace Museum)

Riverside Spring (1934) is an early example of Lang constructing a painting-like landscape through composite photography. It is instructive to compare Lang’s work to a classical landscape painting such as the celebrated Early Spring (1072)—Guo Xi’s vertical hanging scroll made from ink and light color on silk. Similar to the painting, Lang brings together three image sections: a foreground of trees, a middle ground populated with a figure, and a background of mountainous peaks. The major difference is that Lang used separate photographic negatives to create his composition rather than painting this space entirely from his imagination. Because each work is created in the darkroom, with Lang separately placing each negative as well as manipulating the exposure of specific areas, each print is a unique work by the artist’s hand. In Riverside Spring, Lang has skillfully blurred the boundaries between each section so that the borders appear out of focus, almost mist-like, which is also similar to the upper section of Early Spring.

Left: Lang Jingshan, Symbol of Longevity, 1943, 38 x 28 cm, gelatin silver print (Taipei Fine Arts Museum) right: Lang Jingshan, Crane, 1945, 134 x 98 cm, C print (Taipei Fine Arts Museum)

As part of this composite process, Lang also re-used and even re-oriented his negatives, which is why the same figures, boats, and animal subjects frequently appear in different compositions, sometimes with the direction of the negative flipped. Lang would also often use ink to write calligraphy on his works or add his red artist seal to the finished print. Such artistic flourishes indicate that Lang meant his photography to be appreciated and understood as a type of update to traditional Chinese painting, one judged by the same measures.

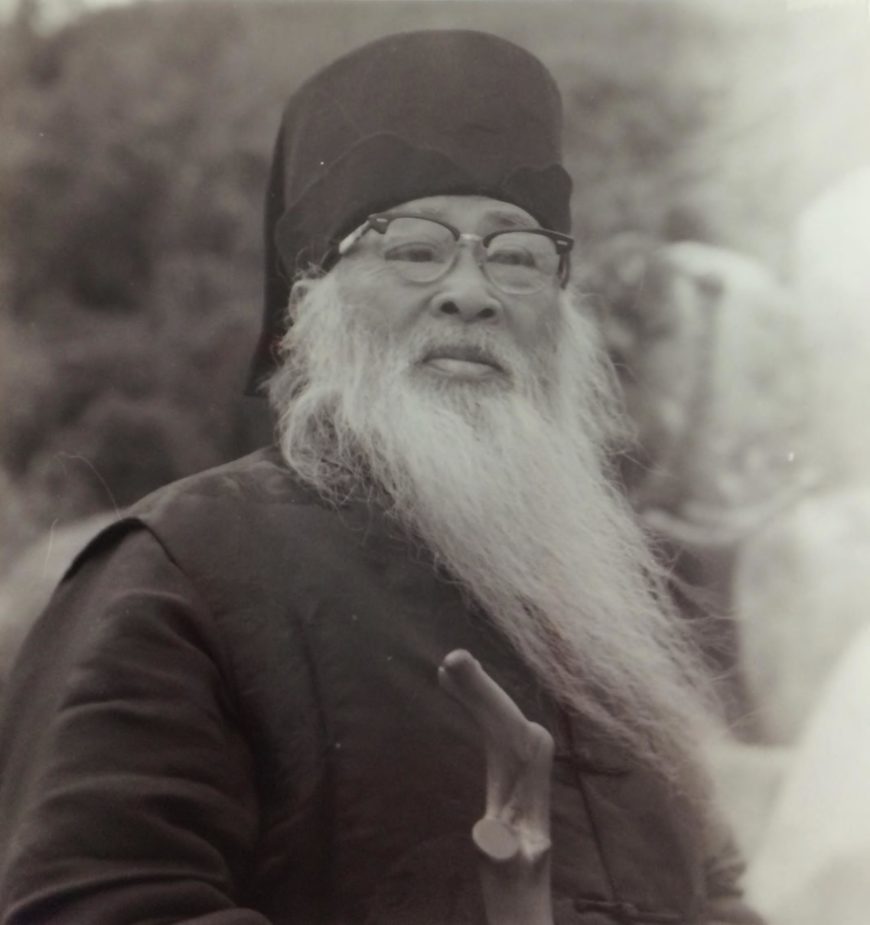

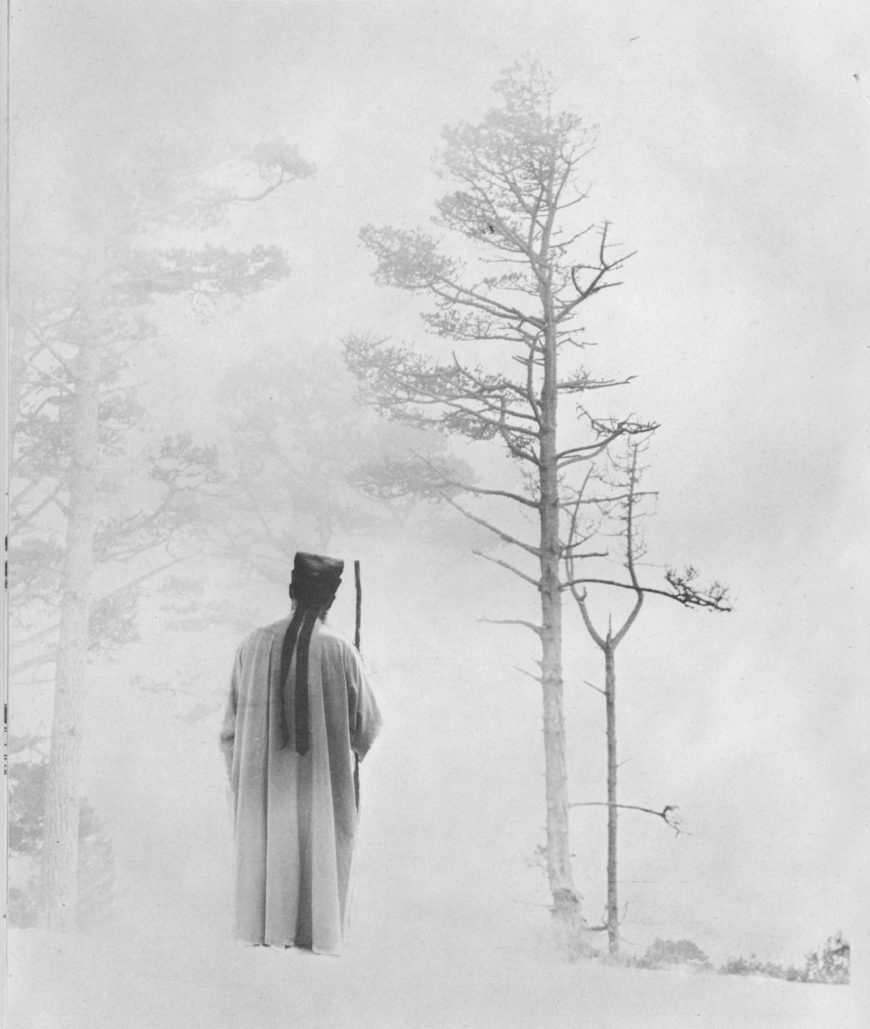

Zhang Daqian wearing a a dongpo hat and holding a walking stick to emulate Su Shi, a Song Dynasty literati artist. Lang Jingshan, Untitled (portrait of Zhang Daqian), photograph (U-M Library Digital Collections. Trans-Asia Photography Review Images)

Expanding the Photographic Genre

Lang Jingshan not only used this composite technique to capture traditional landscapes, he also created portraits and still-life images in the style of Chinese paintings. Lang’s portraits of the artist Zhang Daqian (1899–1983) depict this celebrated painter as a Taoist immortal, with his long beard and wooden staff floating in the clouds or observing nature.

In some photographs, Zhang is placed into a misty landscape. Lang Jingshan, Qinchen ru yunwu (Entering the Mist in Morning), composite photograph reproduced in Badeyuan shejing (U-M Library Digital Collections. Trans-Asia Photography Review Images)

Working together with the painter to compose these photographs, it appears that some of these composite works were even based on Zhang’s own ink paintings. Over the years, Lang assembled and reassembled his photographs drawing on popular Chinese motifs, such as clouds, mountainous peaks, pine trees, bamboo, cranes, and deer, repeatedly working through this traditional visual vocabulary to create novel compositions that strongly resemble and resonate with the aesthetics of Chinese paintings.

With each idealized, highly evocative photographic work, Lang skillfully adapted the composite method to capture the distinctive elements of Chinese painting such as its popular subjects and unique formats. The fragments form language that contemporary Chinese artists continue to draw upon today. It is a language that mirrors the conversations about life, nature, and beauty that have been going on for thousands of years within the Chinese canon.