Combining metallic curls with mottled color, Kōrin’s screens capture the pulsing vitality of early spring.

Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms, 18th century (Edo period), pair of two-fold screens, color and gold leaf on paper, 156 x 172.2 cm each (National Treasure; MOA Museum, Atami). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

0:00:06.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’re in the Museum of Art in the city of Atami in Japan, looking at one of this nation’s national treasures, Ogata Kōrin’s Red and White Plum Blossoms. It’s a Japanese screen pair of two hinged panels.

0:00:22.8 Dr. Beth Harris: And not only are we looking at a National Treasure, but also perhaps the great culmination of the career of one of the most famous Japanese artists, Ogata Kōrin. This is painted late in his career. What we see are two plum trees. The one on the left has white flowers, and the one on the right has red flowers. And in the middle, a stream.

0:00:47.9 Dr. Steven Zucker: What makes this painting so extraordinary is the thin line between naturalism, his understanding of the anatomy of the plum tree, and of the water rushing down the stream, but in a high degree of abstraction.

0:01:02.5 Dr. Beth Harris: Japanese gardens are always artifice, they’re always aesthetisized. The trees are carefully pruned, the bodies of water carefully guided to produce the most heightened aesthetic effects.

0:01:17.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: Let’s look closely at the white plum on the left. We have this broad trunk that floats in space. The ground plane is simply gold. There is no cross hatching, there is no shadowing, there is no outline. He is creating a sense of volume and mass simply through color and placement.

0:01:36.2 Dr. Beth Harris: We have this gold background where we would expect to see other green growth, clouds, sky, and instead, we have this flat, gold background that to me enhances the sense of preciousness of nature. These gnarled branches that have been guided in their growth through careful pruning, to be expressive and to follow the natural growth of the tree. But at the same time, these vertical shoots that feel new as they emerge from the branches.

0:02:12.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: When I first looked at this painting, I did not associate the old trunk of the plum with the branch that enters from the top left. Instead, it seemed to me at first that that was a tree that was growing out of the ground. And it was only as I began to step back and see the panels as a whole, that I realized that that branch was actually part of that larger tree.

0:02:35.8 Dr. Beth Harris: This is, I think, part of the pictorial strategy, to almost zoom in, to abbreviate, to heighten what we’re looking at. And so we only see parts of forms, but we’re also very close to them.

0:02:51.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: This artist was not simply a painter, but he also worked in urushi lacquer, in textiles, in many media.

0:02:58.5 Dr. Beth Harris: Well, his father ran a very high level establishment that provided textiles to the elite. But toward the middle of his life, he also found himself in a position where he had to make a living and he started to paint.

0:03:13.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: The composition, at first glance, seems so simple. A stream in the center with a tree on either side. And yet, there’s nothing symmetrical about this.

0:03:21.9 Dr. Beth Harris: Well, and we also have this contrast between movement and stillness. The stream is moving around rocks and eddies, but then this stillness of the trees and the branches. So, I read this almost as three independent forms, and it reminds me of how we see so often images of three in the Buddhist tradition of Japanese art, where we see the Buddha with a bodhisattva on either side of him.

0:03:53.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: The plum tree, and the plum blossom specifically, is an ancient subject in Japan and in China. It speaks to ephemerality, that is, that beauty is only there for a moment, and then we have to wait for the cycle of the year, for that to come again.

0:04:07.5 Dr. Beth Harris: The plum blossom refers to winter and the very beginnings of spring. So, this transitional moment between the seasons, which are a kind of heightened moment where one is more aware of change.

0:04:23.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: And that must have been especially heightened because this was made so late in the artist’s life.

0:04:28.8 Dr. Beth Harris: If we look closely, we can see that he used a technique where he added more paint on top of little pools of paint that were not quite dry. And you can see the edges formed by that technique, creating a sense of the moss and the growth on the trees and the bark of the trees.

0:04:47.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: And I especially love the green blue lichen, which he produced using malachite.

0:04:51.7 Dr. Beth Harris: Art historians think about this as the height or the great masterpiece of the Rinpa school. And if we think about that word, Rinpa, “Rin,” Ogata Kōrin. And “pa” is school. So this is the school of Ogata Kōrin. It’s not a real school. It’s a group of artists painting in a particular style. And although we think about Ogata Kōrin as the quintessential artist of that school, he’s also very much looking back to other important Japanese artists from 50 or 100 years earlier, most notably Sōtatsu.

0:05:27.5 Dr. Steven Zucker: And to try to characterize the Rinpa school is not easy, but very often the art is lush, colorful. There can be a substantial amount of gold, and there’s often a high degree of abstraction.

0:05:41.1 Dr. Beth Harris: What artists of the Rinpa school often do is take one element and really focus our attention on it, enlarge it. And so instead of having a tree and a stream in space in a garden, we’re just face to face with these natural elements. And, in fact, there is a painting that Kōrin did that’s a copy of a painting by Sōtatsu, where we see a very similar tree to the one we see here on the right, as though Kōrin has taken that tree and enlarged it and made it the focus of this very decorative and stylized image.

0:06:23.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: Looking at this painting, it’s impossible not to think about Gustav Klimt, of the use of gold, of pattern, of the formality, of the rejection of clear space, of the interest in abstraction and geometry.

0:06:37.1 Dr. Beth Harris: So much of the Art Nouveau movement, the Secession movements at the end of the 19th and early 20th century, certainly looking to Japan, something that began in 1852 when Japan opened up to the West.

0:06:50.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: Like so many light-sensitive works of art in Japanese museums and monasteries, these panels are only brought out generally once a year, in late winter, when the plum trees bloom. And so we’re so lucky to be here in Atami to see this painting now.

A landscape transformed

Right screen (detail), Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms, 18th century (Edo period), pair of two-fold screens, color and gold leaf on paper, 156 x 172.2 cm each (National Treasure; MOA Museum, Atami; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In Red and White Plum Blossoms, Ogata Kōrin transforms a very simple landscape theme—two flowering trees on either side of a brook—into a dream vision. Executed in black ink and blotchy washes of gem-like mineral color on a pair of folding screens, the image seems both abstract and realistic at the same time. Its background, a subtle grid of gold leaf, denies any sense of place or time and imbues everything with an ethereal glow. The stream’s swelling metallic curls and spirals are a make-believe of flowing water, and its sharply tapered serpentine contour lines angle the picture plane in an unnatural upward tilt. The trunks of the trees are nothing more than pools of mottled color without so much as an outline. These forms and spaces appear flat to the eye. Yet the artist’s intimate knowledge of how a plum tree grows can be seen in their writhing forms and tangle of shoots and branches.

Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms, 18th century (Edo period), pair of two-fold screens, color and gold leaf on paper, 156 x 172.2 cm each (National Treasure; MOA Museum, Atami; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Left screen (detail), Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms, 18th century (Edo period), pair of two-fold screens, color and gold leaf on paper, 156 x 172.2 cm each (National Treasure; MOA Museum, Atami; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Enveloping us in spring

In planning its imagery, Kōrin closely considered the function of the folding screen within the traditional Japanese interior. The two sections would have been positioned separately yet near enough to each other to define an enclosed space. At 156 cm (or approximately 67 inches) in height, they towered over the average Japanese person of the day. Kōrin depicted only the lower parts of the trees, as if viewed from very near: the tree with red blossoms thrusts upward from the ground and out of sight; the white pushes leftward out of view and then, two slender branches appear to spring back diagonally downward from the top corner and jab upward. With each screen standing hinged at its central fold, a viewer experiences these exaggerated two-dimensional images in three dimensions. Stopping us in our tracks by confounding logic with this combination of pure design and intimate naturalism, Kōrin envelops us in the pulsing vitality of early spring.

Rinpa, or “School of Kōrin”

An acknowledged masterpiece painted toward the end of his life, Red and White Plum Blossoms exemplifies a style that for many epitomizes Japanese art. It has profoundly impacted modernism in the West, most famously in the work of Gustav Klimt. Since the 19th century, this combination of abstraction and naturalism, monumental presence, dynamism, and gorgeous sensuality has commonly been referred to as Rinpa, or “School of Kōrin.” But Kōrin neither originated this aesthetic, nor presided over a formal school. More accurately, he stood at the forefront of a loose movement of like-minded artists and designers in various media. Rinpa first appeared a century earlier, in the brilliant relationship of a gifted calligrapher, connoisseur, and intellectual named Hon’ami Kōetsu, and an equally gifted painter of fans and screens, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, who created works that aimed to satisfy the luxurious tastes of 17th-century Kyoto’s aristocrats and wealthy merchants.

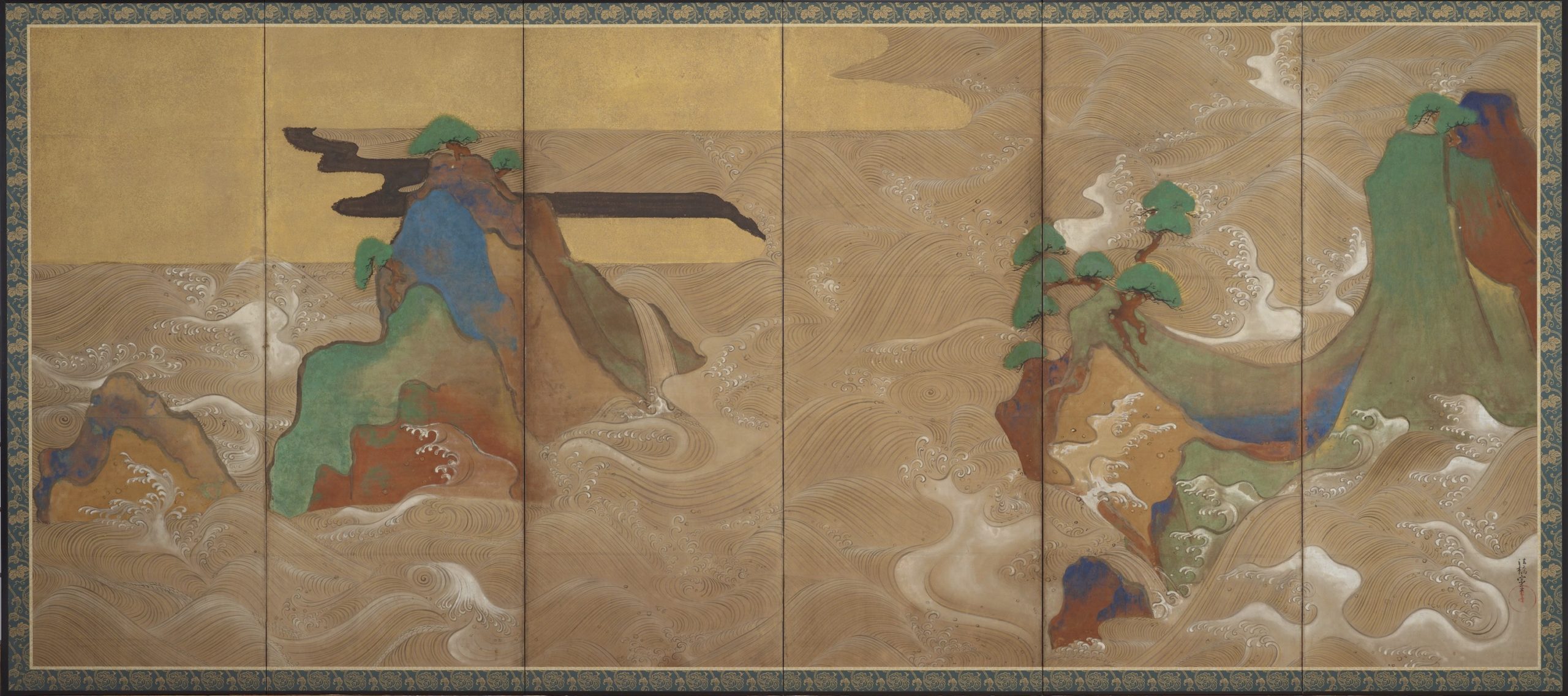

Tawaraya Sōtatsu, Waves at Matsushima, c. 1600–40, right side of a pair of six-panel folding screens, ink, color, gold, and silver on paper (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.)

Entranced by a few of Sōtatsu’s paintings that he saw in the collection of a patron, Kōrin taught himself the techniques: images pared to bare essentials and then dramatically magnified, emphasis on the interplay of forms, colors, and textures, and unconventional adaptations of ink painting methods. These methods included tarashikomi, or dilute washes of color blended while very wet, and mokkotsu, or “bonelessness,” which creates forms without exterior outlines. Some scholars now use terms such as Sōtatsu-Kōrinha, Kōetsuha, and Kōetsu-Kōrinha rather than Rinpa, in recognition of its actual origins. Yet Kōrin is owed a great debt as the one who revived a dazzling creative approach from obscurity and whose vibrant works firmly established his own reputation.

White blossoms (detail), Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms, 18th century (Edo period), pair of two-fold screens, color and gold leaf on paper, 156 x 172.2 cm each (National Treasure; MOA Museum, Atami; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A profligate who squandered his family’s enormous wealth, Kōrin benefitted from the wide design experience afforded by its position as one of Kyoto’s most distinguished producers and purveyors of fine textiles. This he combined with painting studies in one of Japan’s preeminent studios. His numerous works in this sophisticated style thus encompass many media, formats, and subjects—paintings in color and ink on large screens, small albums, fans, hanging and hand scrolls, printed books, lacquers, ceramics, and even textiles.

Initially inspired by Japanese classical literature, the Rinpa movement’s attention soon extended to themes from nature, including Chinese motifs that may have influenced Kōrin’s choice of plum trees for this painting. Looking now at the impact of his work from over three centuries ago, it seems incredible that a vision so dramatic, luxurious, and radical could ever have fallen into obscurity.