Left: brocade skirt, 20th century (Varanasi), silk, gilt metal, and cotton, 103 cm long, 352 cm circumference (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru); center: Bandhani Odhani, early 20th century (Gujarat), silk, 209 x 140 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru); right: Kalamkari, late 20th–early 21st century (Andhra Pradesh), cotton and natural dyes, 289 x 237 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

South Asia is home to hundreds of textile traditions that have evolved over centuries. Its regionally-varying resources, methods of production, and decoration techniques have given rise to diverse practices of creating cloth with different textures, colors, designs, and functions. Some of these are luxurious and ornamental, crafted for special occasions and ritual use. Others, whether plain or patterned, are used as daily attire or for domestic purposes.

While the breadth of traditions across the subcontinent can be approached in many ways, textile scholar Ruchira Ghose offers us an accessible entry point through which we can classify textiles. Her approach is based on the stage of weaving at which designs or patterns are incorporated into the fabric. These classifications are:

- Pre-Loom: When patterns are predetermined on yarns that are dyed in specially formulated sections before they enter the loom.

- On-Loom: When plain and patterned textiles are woven on the loom with the use of threads of different colors and materials that can produce a number of designs and patterns based on various types of intersections between the warp and weft threads.

- Post-Loom: When finished textiles that are off the loom are decorated using techniques such as dyeing and embroidery.

Let’s examine a selection of some of the most prominent textile traditions across the Indian subcontinent based on these classifications.

Ikat, 18th century (Surat, Gujarat), silk, 15 x 37 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Pre-loom and on-loom: woven designs

Ikat

Ikat is a complex technique of weaving fabrics in which designs are calculatedly incorporated on cotton or silk threads before they are placed on the loom. This process involves stretching the yarns and marking them with the desired patterns. These are then tied with rubber bands at strategic points corresponding to a planned design, following which they are dyed. The tied sections of the fibers remain un-dyed, while the rest of the areas take on the color. When woven into finished textiles, these yarns create soft patterns with undefined edges. This blurred quality is caused by the dye bleeding into the tied sections and is a distinctive characteristic of most Ikat fabrics.

Patola, late 19th–early 20th century (Patan, Gujarat), silk, 324 x 134 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Among the diverse range of Ikat traditions found in the subcontinent, the most well known is practiced in Patan, Gujarat. Here, Ikat textiles known as Patola feature vividly-colored motifs across grid-based formats. Compared to other Ikats, the designs featured on Patola are known for their crisply-defined outlines. Achieving this level of precision demands a rare expertise, as this complex process involves the perfectly planned intersection of pre-dyed warp and weft threads. Deeply valued for their intricate patterns, Patola were historically treasured by members of the aristocracy in the Indian subcontinent and other parts of the world.

Weaver producing a Banarasi brocade sari on a jacquard loom (photo: Unstable.atom, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Brocades

Brocades are fabrics that incorporate patterns using extra warp or weft threads during the process of weaving. Often made of gold or silver, these threads create embossed patterns across cotton or silk textiles that can easily be mistaken for embroidered designs due to their dense nature. They often cover so much ground that they make textiles appear to be entirely made of gold. However, brocades that incorporate supplementary cotton or silk threads are relatively subdued in appearance. While brocades were historically woven entirely by hand—a laborious and time-intensive process—the invention of the jacquard loom in the nineteenth century greatly sped up their production.

Banaras brocade sari, 20th century (Varanasi), silk and gilt metal, 452 x 112 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Due to the expensive nature of the materials used to make them, brocades were historically commissioned by rulers. Today, prominent centers for brocade-weaving in the Indian subcontinent include Banaras (present-day Varanasi), Kanchipuram, Gujarat, and Karachi. These textiles are popularly worn on weddings and other special occasions.

Left: textile production using the Ajrakh block-printing method (photo: Kashif11, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: detail of Ajrakh textile, Khatri community (photo: Rick Bradley, CC BY 2.0)

Post loom: printed, resist dyed and painted textiles

Ajrakh

Ajrakh is an ancient block-printing method. It is characterized by intricate patterning in vibrant, long-lasting shades of red and blue. In block printing, the dye is applied directly to a wooden block, which is then stamped on the fabric, leaving an imprint of the design carved on it. The process of carving these blocks, integral to the Ajrakh process, is itself a prominent craft tradition.

While block printing is the most significant step used in making Ajrakh textiles, the complete process involves more than twenty steps that can sometimes take over a month. Ajrakh is typically associated with the Khatri community, who have lived on both sides of the present-day India-Pakistan border, and the technique is practiced in both countries even today.

Dabu

Similar to Ajrakh, Dabu is also a prominent method of block-printing commonly practiced in Rajasthan and Gujarat. However, unlike Ajrakh—in which designs are printed directly onto fabric using carved blocks and dye—Dabu is a resist-printing method that uses a substance known as a resist, which prevents the textile from absorbing dye in specific areas, creating patterns in the cloth.

In the case of Dabu, the resist may include a combination of a wet mud paste, lime, or sand. The resist is transferred to the surface of the cloth using a wooden block, after which the fabric is immersed in a dye. The resist is only washed off once the desired color is achieved, although the process may be repeated so that solid designs can be printed on top of the untouched areas. Unlike Ajrakh, which often has intricate patterning carved into the wooden blocks, Dabu prints are characterized by their solid shapes and silhouettes of motifs.

Left: detail of Bandhani sari (photo: Mandayamr); right: detail of Bandhani dupattā (photo: RubyGoes, CC BY 2.0)

Bandhani

Bandhani, another resist-dyeing technique, is prominently practiced in the Kutch region of Gujarat and Rajasthan. The term itself derives from the word bandh, which means “to tie.” As part of the dyeing process, a woven fabric is first marked at strategic points, folded to produce symmetrical sections, pinched and tied at these marked sections and then dyed with the desired colors. The resulting pattern is characterized by clusters of white dots or squares at the points where the fabric was tied. These dots, which appear across the fabric, are the result of careful planning by the hands of expert artisans. This process may be repeated multiple times to achieve different layers of colors or even different shades of the same color. Used for a range of purposes, Bandhani is one of the most prominent tie-dyeing textile traditions in the Indian subcontinent.

Kalamkari textile, 21st century (Andhra Pradesh), cotton, 59 x 169 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Kalamkari

Kalamkari is a textile tradition known for its vivid, hand-painted imagery. Originating from the Persian words kalam (“pen”) and kari (“work”), Kalamkari literally translates to “the work of the pen.” Kalamkari textiles are known for the depiction of scenes from Hindu mythology or royal conquests as well as nature-inspired motifs.

In addition to being drawn using a pen-like tool, these textiles are often produced with a combination of other techniques such as mordant dyeing, resist-dyeing, and block printing, in a process that can involve up to twenty-three steps.

Kalamkari textile, mid-19th–mid-20th century (Machilipatnam, Andhra Pradesh), cotton and natural dyes, 81 x 123 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Kalamkari has been practiced across different regions, including Burhanpur in Madhya Pradesh and Srikalahasti and Machilipatnam in Andhra Pradesh. As one of the most prominent painted textile traditions of the subcontinent, works of Kalamkari were also widely traded around the world.

Stiching a Nakshi Kantha (embroidered quilt), Bangladesh (photo: Faizul Latif Chowdhury, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Post loom: embroidered textiles

Kantha

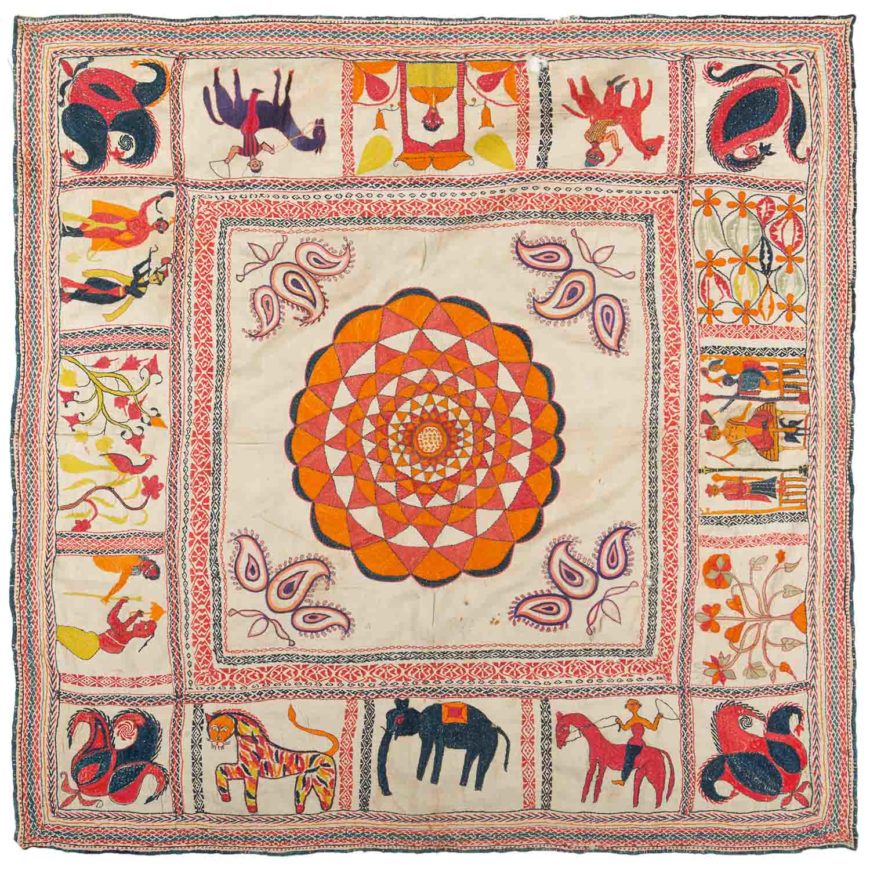

Kantha, c. 1890 (Undivided Bengal), cotton, 93 x 93 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Kantha is a type of embroidery that originated in pre-partition Bengal. Traditionally practiced by women, Kantha-making was largely a domestic activity, centered around the re-use of old or discarded textiles. These fabrics are first rendered with vivid motifs and scenes, and then joined together using a running stitch. The term Kantha may refer to either the stitch or the fabric itself.

The look and feel of a Kantha may depend on the size, thickness, and material of the repurposed fabrics, as well as the embroidery, design and layout of its composition. Kanthas tend to be narrative in nature and are often inspired by the daily lives and surroundings of their makers.

Bagh Phulkari, 20th century (Undivided Punjab), cotton and floss silk, 243 x 130 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Phulkari

Also traditionally practiced by women within domestic spaces, Phulkari is a type of embroidery that originates from pre-partition Punjab, and is known for its glossy, satin-like texture. The term Phulkari translates to “flower work” and refers to the characteristic floral motifs rendered in the form of naturalistic or geometric shapes. The embroidery is most commonly seen on cotton shawls and is characterized by the use of a darning stitch that runs through the reverse side of the fabric. The making and motifs of these elaborate shawls are embedded in the wedding traditions of the region. Triangles, for instance, are emblematic of the red, vermillion mark made on a bride’s forehead and along her hair parting line as a symbol of her married status.

The hundreds of textile traditions in the subcontinent have developed from the constant exchange of skills, designs, and techniques, as well as generations of rigor and practice. Because of this, it is often difficult to define their historical trajectories or sometimes even differentiate traditions from one another. The resulting variety in the region’s handloom and handcrafted traditions is a testament to the technical expertise, creativity, and intimate knowledge of materials that textile artisans possess.

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy