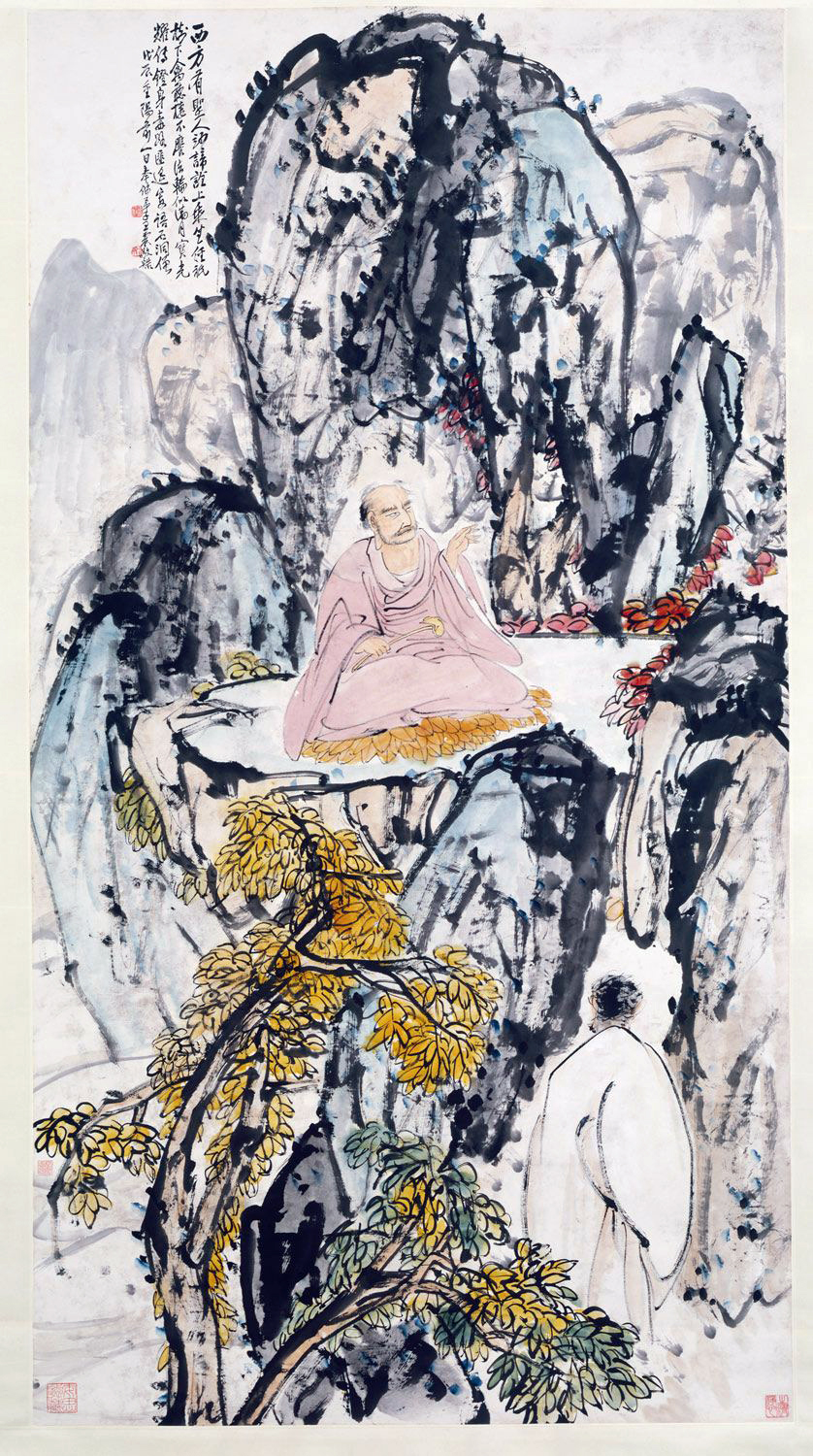

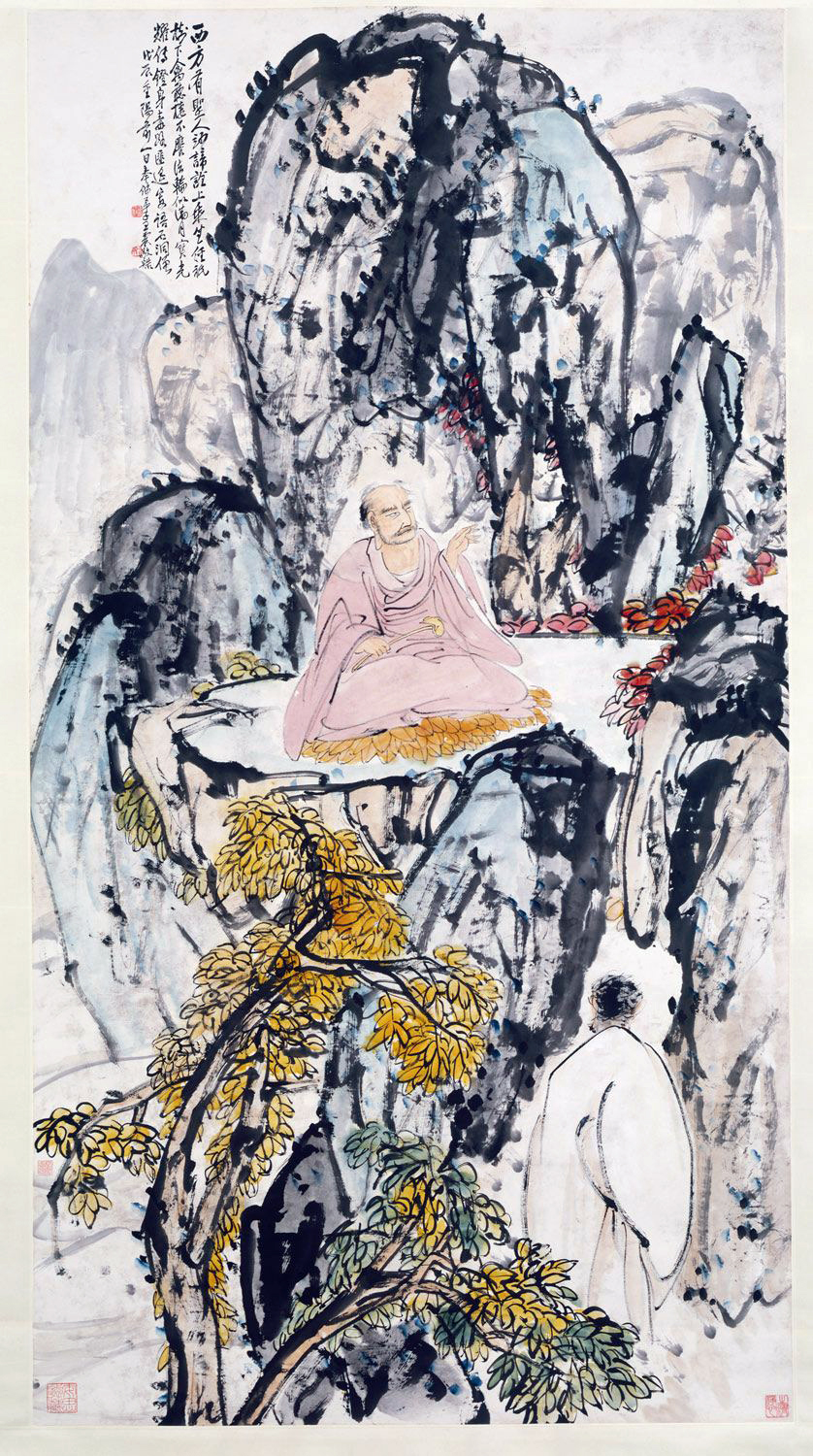

Wang Zhen, Buddhist Sage, dated October 20 1928, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 199.4 x 93.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

How modern is this Chinese painting by Wang Zhen?

Of course, it’s a trick question; it all depends on what you mean by “Chinese,” or by “modern.” This hanging scroll showing a figure seated in a swirling landscape of restless ink strokes is painted in watercolor on paper. Its vertical format, along with the medium, had been used in China for centuries. And the subject matter—an ancient Buddhist teacher preaching on a mountain ledge, his raised hand gesture indicating he is in the process of imparting wisdom to the seeker who tentatively approaches him from the bottom edge of the picture—seem to situate it within “tradition,” as opposed to “modernity.” Images of such Buddhist teachers had a long history in Chinese painting, as we see in a thirteenth-century hanging scroll showing Bodhidharma meditating while facing a cliff.

Anonymous, Bodhidharma Meditating Facing a Cliff, late 13th century, hanging scroll, ink on silk, 203.2 x 63.5 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

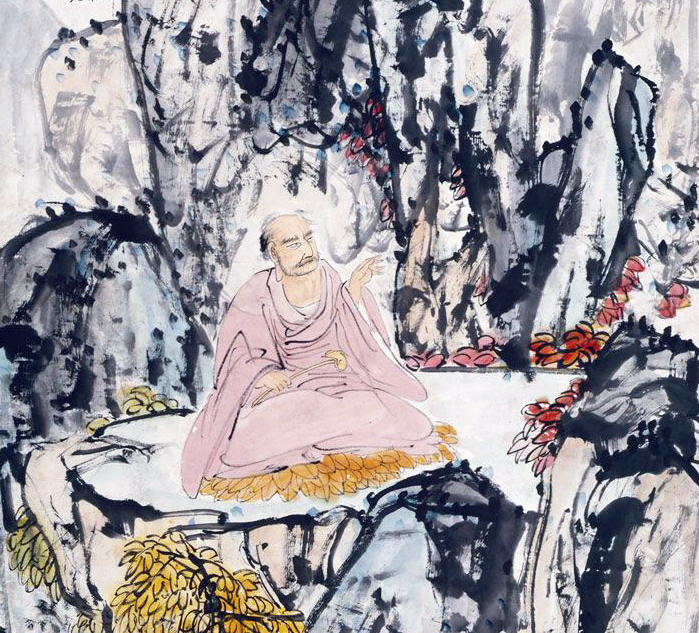

Wang Zhen, Buddhist Sage (detail), dated October 20 1928, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 199.4 x 93.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

But a closer investigation of Buddhist Sage (a title given by the museum where the scroll now resides) and of its painter, suggests these neat oppositions are unhelpful in thinking about art produced in China in the Republican period (1912–1949), the decades between the end of the imperial Qing dynasty (1636–1912) in 1911 and the coming to power of the Chinese Communist Party in 1949. The theme may be an ancient one, but the manner in which it is treated, with very loose swirling brushwork and an explicit emphasis on color, are unlike any Chinese painting painted before the nineteenth century. The density of the composition, where ink covers the whole surface and no blank space is left unpainted, is also something not seen in earlier Chinese painting (compare the large areas of silk left blank on the earlier thirteenth-century painting of the same subject).

The format, medium, and subject matter may have a long history—so too do early twentieth-century European paintings like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, with both its medium (oil on canvas) and subject matter (female nudes). Yet it is Picasso’s painting which is often described as “a breakthrough,” “a modern masterpiece,” while works like Buddhist Sage are often described as “traditional Chinese painting,” as if it was impossible for a work of art to be both “Chinese” and “modern.”

The artist as celebrity

Buddhist Sage was painted by Wang Zhen (also known as Wang Yiting). In China, the year of his birth was the “Sixth Year of the Tongzhi Period of the Great Qing” (1867 in the Western calendar); he died in the “Twenty-seventh year of the Chinese Republic” (1938). He was part of a generation that lived through traumatic times, with China buffeted by internal and external wars, political instability, and natural disasters.

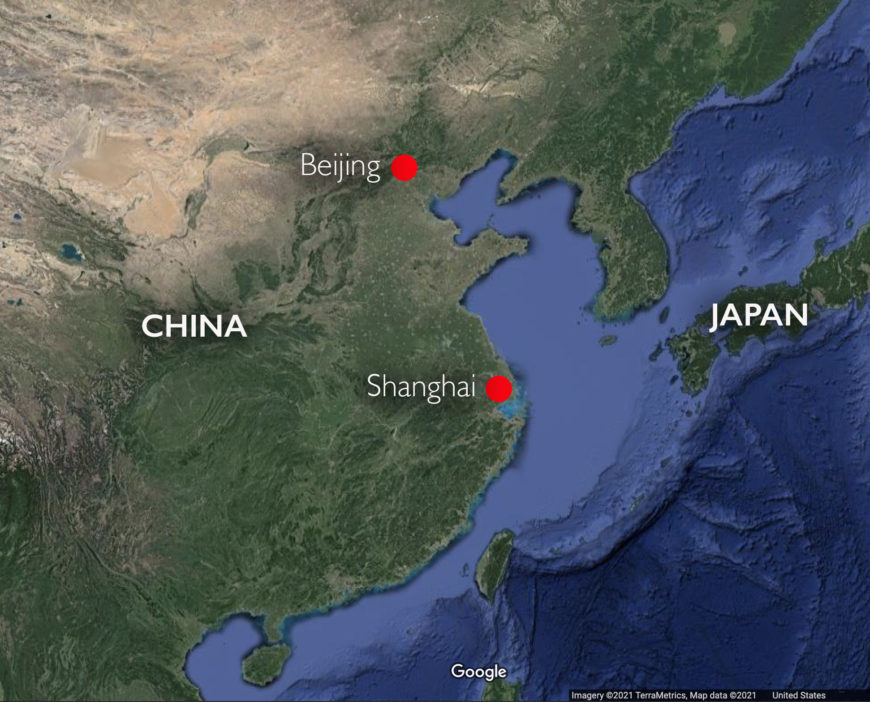

Wang Zhen was born in the great coastal city of Shanghai, where his family had moved to avoid the horrors of the civil war between the Qing and the “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace,” which killed up to seventy million people, and which ended only three years before Wang was born. His family, neither wealthy nor impoverished, were dealers in cloth and clothing. In his early teens Wang Zhen was apprenticed to a bank, and showed the kind of aptitude for business which meant that by the time he was forty he was a prominent figure managing a major shipping company. This was a Chinese-Japanese joint venture, and it was in the service of Japanese concerns that Wang established himself as one of the most prosperous and successful members of the business community in Shanghai, the city which was the key point of access for the commercial and political interests of European, American, and Japanese empires in China.

Wang Zhen had been active in campaigns to overthrow the Qing empire, to build a strong and independent China, but he abandoned the messy (and violent) world of politics after the Republic was founded in 1912. Instead he devoted himself to his many commercial interests, as well as to the spheres of charitable activity and culture, most notably his participation in various artistic societies and his production of a large body of painting.

Presentation photography commemorating the visit of Albert Einstein (center front) to the garden of Wang Zhen, the second figure from the right in the front row, 1922

He was an extremely prominent figure, what we would now call a major celebrity, his activities often mentioned in contemporary newspapers. For example, he hosted the scientist Albert Einstein, visiting Shanghai in the course of a world tour in 1922.

Wang Zhen, Buddhist Sage, dated October 20 1928, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 199.4 x 93.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The subject

Buddhist Sage carries a poetic inscription that identifies who and what we see in the painting. It reads:

A sage from the West

Preaches the miraculous doctrine of the Upper Vehicle.

Preaching, he sits under a bodhi tree,

With roosting birds listening in silence.

The Wheel of the Law is as bright as a full moon,

Its precious light illuminating the lamp of transmission.

Ailing worshipers travel from afar

To receive guidance from the monk at the stone cave.One day before the Zhongyang Festival [the 9th day of the 9th month] 1928. Respectfully painted, the Buddhist Wang Zhen

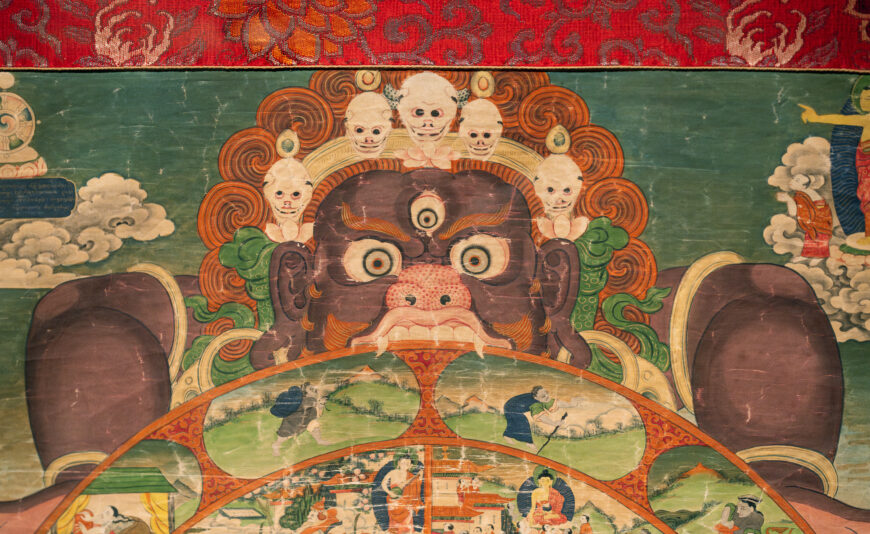

The “sage from the West” is the semi-legendary founder of the Chan sect of Buddhism, Bodhidharma, active in the early 5th century C.E. The earliest Chinese sources to mention him state that he was a visitor to China from “the Western regions,” a large and vague area which encompasses the whole of South and Central Asia, as far as modern Iran; some sources claim he was the son of an Indian king. In later centuries, many legends and miracle tales are associated with him, stressing his emphasis on meditation over ritual as the key to the achievement of enlightenment. In one of these legends, he refuses to accept a supplicant named Huike as his student until Huike demonstrates sufficient sincerity by severing his own arm. Huike, later revered as the Second Patriarch of the Chan School of Buddhism, is represented in both the Bodhidharma paintings above, the thirteenth-century one from Cleveland (where he wears a monk’s robe), and the Wang Zhen scroll, where he appears dressed in white at the bottom of the scroll.

This image of Bodhidharma is likely to have had a personal meaning for Wang Zhen, as well as being suitable for sale or gift to other Buddhist devotees, whether in China or Japan, where “Zen” (Chan Buddhism in China) was coming to be seen as the most relevant of Buddhist schools to contemporary thought. The artist’s self-identification as a Buddhist is an important part of his identity. His mother and grandmother were both Buddhists, and his own religious faith deepened after the political assassination of a close friend in 1913. In 1916 he undertook the formal “Three Refuges” , his vows being administered by Taixu, a prominent monk attempting to create a Buddhism that was both Chinese and modern. Active in many Buddhist organizations, and funding a great deal of charitable activity (for example in the wake of a great earthquake which devastated Japan in 1923), Wang Zhen was a committed believer in Buddhist precepts.

Buddhist Sage is a reminder that the most “Chinese” of Buddhist sects (Chan) was not only a meaningful part of the modern world, but was in its origins something brought to China from “the Western regions,” by a foreigner, the sage Bodhidharma. It shows how Wang Zhen’s art challenges simplistic categories, of “Eastern” and “Western”, and undermines any too-neat division of Republican China’s art into “traditional” and “modern.”

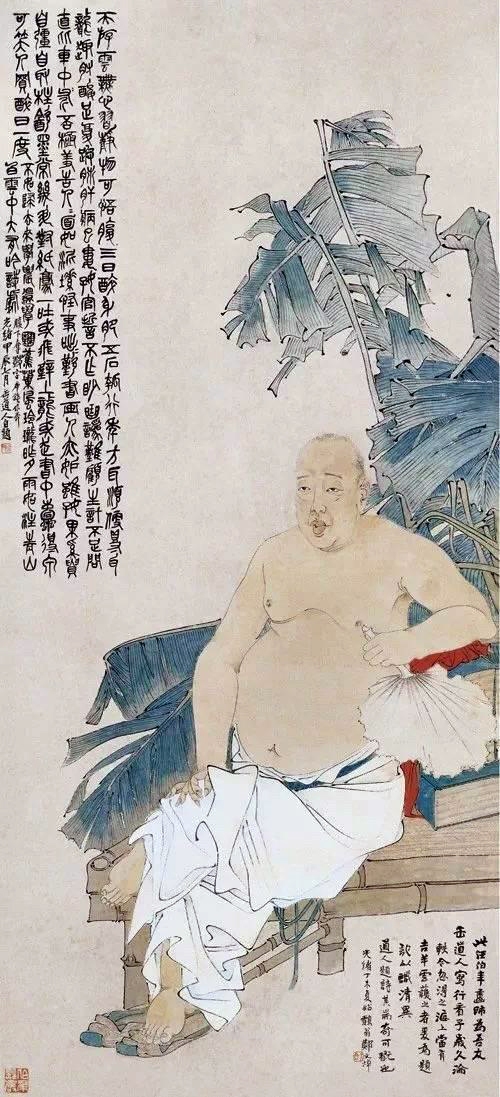

Ren Yi, Portrait of Wu Changshuo Enjoying the Cool Shade of Banana Palms, 1888, hanging scroll: ink and color on paper, 129.5 x 58.9 cms. Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou

Wang Zhen and the “Shanghai School”

Wang Zhen began painting early in life, his earliest surviving works dating from 1885, when he was in his late teens. He acknowledged as teachers two members of the Shanghai School, the more famous of these being Ren Yi, also known as Ren Bonian. Through his connection to this famous master, Wang Zhen can himself be thought of as a member of that same Shanghai School. Ren Yi’s Portrait of Wu Changshuo captures the innovative nature of the artists working in the great commercial city. Although the nude human figure had played little or no part in Chinese painting of previous centuries, Ren is unafraid to share with the viewer his subject’s enjoyment in casting off the robes of respectability to achieve some relief from the searing summer heat. The careful delineation of the facial features suggests the artist’s exposure to imported types of picture-making, as well as to photography’s ability to capture a likeness. This is a real person, and not a type.

Like some other art historical terms “Shanghai School” (Hai pai, in Chinese) began as a derogatory term, used by artists in the old imperial capital Beijing to dismiss the work of Shanghai artists they saw as too eager to please unsophisticated customers, work that was flashy, highly-colored, superficially attractive. Painters like Ren Yi used a range of new imported pigments, but also negotiated with imported forms of picture-making, as well as with the new technology of photography, to make art which was vivid and immediate. This was an art they sold openly, using the new periodical press to advertise their work in a “modern” way which deliberately flouted the conventions of the “literati” life aspired to by Chinese elites in previous centuries. Wang Zhen published price lists for his work in 1887, 1889, 1922, 1925, and 1930. [2] By the time he painted Buddhist Sage in 1928 he was one of the most commercially successful artists in China, who also used his considerable prestige to promote the price lists of other artists, including work by women painters.

Wu Changshuo, Peonies in a Bronze Vessel. Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 133 x 60 cm (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Bequeathed by Dr Oliver Impey, 2007).

In 1911 Wang Zhen came to know another of Ren Yi’s pupils, a man of an older generation named Wu Changshuo, who had abandoned a stuttering career as an official of the imperial government to live off his much-admired calligraphy, an art form where he was innovative in developing new forms of the script derived from the most ancient models. It is Wu Changshuo’s features (as well as his ample belly) which are at the centre of the Ren Yi painting shown above. Wu’s calligraphy was already highly regarded by Japanese connoisseurs, and when he increasingly took up painting after his move to Shanghai in 1912 he rapidly became a much-sought-after artist. In 1914 Wang Zhen promoted a solo show of Wu’s work in a Japanese restaurant patronized by Chinese intellectuals as well as by the Japanese community, then the largest group of foreigners in Shanghai. [1] Wu Changshuo was deeply committed to making ancient forms of the Chinese script meaningful in the current artistic context, and this engagement with the art of the past, but in a now vastly changed world, can also be seen in his painting of flowers in a bronze vessel. The large blooms of peonies are rendered in the wet ink that was a Shanghai school trademark, and which contrasts with the image of the bronze vessel, which is not painted but formed by a complex composite rubbing technique in which the elaborate decoration of its surface is transferred to the paper.

Wang Zhen’s painting of the sage Bodhidharma is capable of evoking many thoughts in the type of viewer for whom it was made. Its style and its inscription clearly signal that it is the product of a painter very closely associated with Shanghai and its commercial prosperity. Its subject, a demanding master and determined disciple, references a social relationship which must have had meaning for many who saw it, as did its strong adherence to the tenets of Buddhist belief. But above all it as a work which asserts that both these forms of art and religious beliefs have meaning now, that they can be “modern” too.