Essay by Lee Soomi

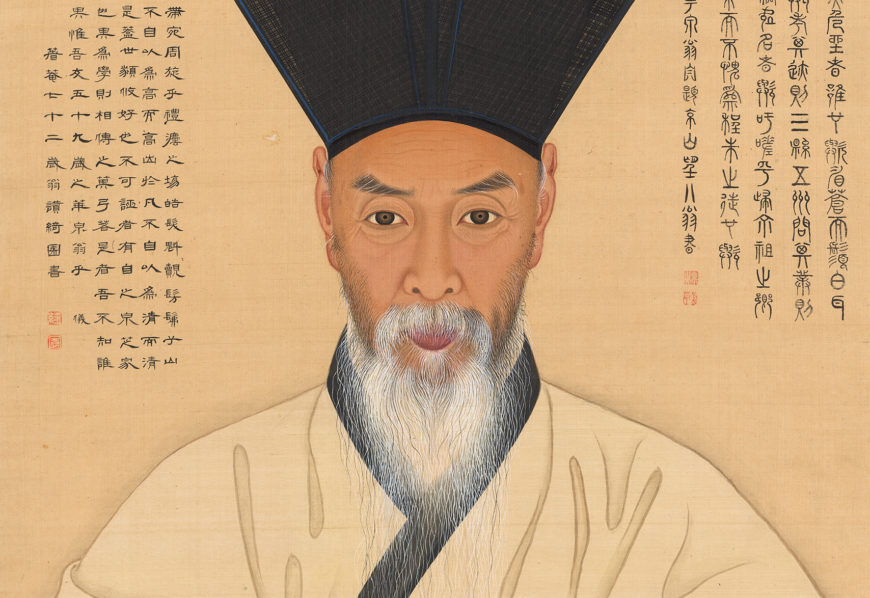

Yi Myeonggi and Kim Hongdo, Portrait of Seo Jiksu, 1796, Joseon Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 148.8 × 72.4 cm, Treasure 1487 (National Museum of Korea)

In this painting, a literati scholar stands alone, attracting and impressing the viewer with his penetrating gaze and look of quiet confidence. The famous scholar Seo Jiksu is wearing a pointed hat known as a “dongpagwan” (東坡冠), which the literati generally wore in their homes. Indeed, the semblance is so indelible that this very image instantly comes to mind when people envision a Joseon scholar. Created in 1796, when Seo Jiksu was sixty-two years old, this outstanding portrait is the work of not one, but two of the most renowned court painters of the day; Yi Myeonggi painted the face, while Kim Hongdo painted the body. Given the superior quality of this work, it is little surprise that both artists were also commissioned to paint the royal portrait of King Jeongjo (not shown here).

For added depth, the eyes were outlined with brown circles, while the pupils were highlighted with orange pigments for enhanced vivacity. Yi Myeonggi and Kim Hongdo, Portrait of Seo Jiksu (detail), 1796, Joseon Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 148.8 × 72.4 cm, Treasure 1487 (National Museum of Korea)

Seo Jiksu: Connoisseur of Literature and Art

The most striking aspect of the painting is Seo Jiksu’s piercing gaze. For added depth, the eyes were outlined with brown circles, while the pupils were highlighted with orange pigments for enhanced vivacity. The cream-colored robe is also magnificent, with huge, billowing sleeves that cover the hands and convey the ease and abundance enjoyed by a man of nobility. With a wide collar wrapping the neck, a black band casually tied in the front, soft but conspicuous folds, and a low hemline that reaches the ankles, the robe manifests the typical appearance of a dignified literati scholar.

The viewers’ attention is drawn to the bright white socks on the mat. This is one of the few Joseon portraits in which the sitter is depicted without shoes. Yi Myeonggi and Kim Hongdo, Portrait of Seo Jiksu (detail), 1796, Joseon Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 148.8 × 72.4 cm, Treasure 1487 (National Museum of Korea)

In most portraits, the feet of the sitter fail to attract much notice, but this is a rare exception, being one of the few Joseon portraits that depicts its subject without shoes. Seo is standing on a fine mat with his white socks conspicuously exposed beneath the hem of his robe. The bright white color of the socks interrupts the rhythm of the black hat and black band for a distinctive contrast, which is supported by the horizontal lines on the mat. All of these details combine to create a sense of power and serenity that defines the atmosphere of the painting.

But who is this man emitting such an air of strength and nobility? Seo Jiksu, whose courtesy name was “Gyeongji” (敬之), passed the literary licentiate examination in 1765. Despite starting out as an official charged with maintaining royal tombs, he eventually rose to become the first secretary (都正) of the Royal House Administration (敦寧府).

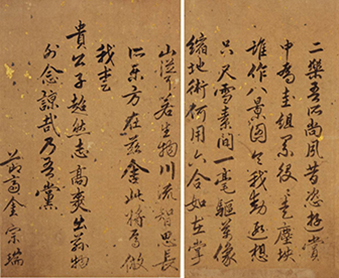

Inscription in the upper right corner. Yi Myeonggi and Kim Hongdo, Portrait of Seo Jiksu (detail), 1796, Joseon Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 148.8 × 72.4 cm, Treasure 1487 (National Museum of Korea)

The inscription in the upper right corner was written by Seo Jiksu himself. Notably, some parts of the inscription have been corrected in ink, demonstrating that this is an unofficial and private portrait. In the inscription, quoted below, Seo Jiksu expresses the contemporaneous view of portraiture:

Yi Myeonggi painted the face and Kim Hongdo painted the body. Despite the best efforts of these renowned painters, this work is missing some intangible aspect of my essential character. How regrettable! Maybe I wasted my spirit and vitality by traveling to majestic mountains and producing meaningless writings, rather than withdrawing from the social world for a life of solitude, fully devoted to my studies. But looking back, I can at least say that I have maintained some dignity by abstaining from a worldly life.

(李命基畫面, 金弘道畫體. 兩人名於畫者, 而不能畫一片靈臺. 惜乎.

何不修道於林下, 浪費心力於名山雜記. 槪論其平生, 不俗也貴).

Can a Portrait Represent the Mind?

Joseon portraits are like photographs, enabling us to not only envision the outward appearance of people of the past, but also to contemplate their inward psychology. At the time, a royal portrait of the Joseon king represented the physical presence of the king himself, and thus embodied the entire nation.

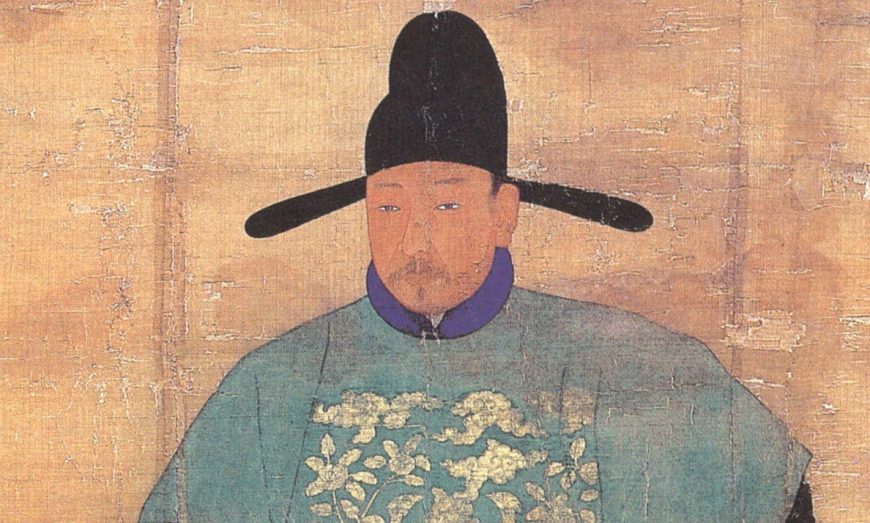

Portrait of Yun Geup shows the hat (“samo,” 紗帽) and robe of a government official. Joseon Dynasty, silk hanging scroll, 224.0×105.5cm, Treasure 1496 (National Museum of Korea)

Similarly, portraits of “gongsin” (“meritorious subjects,” 功臣) who had made notable contributions to the country and “giro” (high-ranking officials over the age of seventy, 耆老) were produced as models for their families or the general populace. These figures were almost always depicted in a very solemn manner, seated in a chair wearing a hat called a “samo” (紗帽) and the robe of a government official. Serving as national symbols of loyalty and political instruments for the government, portraits of revered officials were produced by the most renowned court painters of the time.

Yi Myeonggi and Kim Hongdo, Portrait of Seo Jiksu (detail), 1796, Joseon Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 148.8 × 72.4 cm, Treasure 1487 (National Museum of Korea)

In contrast with portraits showing the official’s hat and robe, this portrait depicts Seo Jiksu in his casual everyday clothes—known as “yabok” (野服)—consisting of a scholar’s robe (made from white hemp with black trim) or another plain robe, along with either a “bokgeon” (black hat with rear flap) or a black pointed hat called either a “dongpagwan” or “jeongjagwan.” Originally, the term “yabok” was used to refer to clothing worn by literati scholars who had not taken a government post. Thus, representing the austere aesthetics and elegance of a true Neo-Confucianist, so-called “yabok portraits” were generally preferred by “sarim” (士林), a group of literati scholars who strictly interpreted and emphasized Neo-Confucianism. But as Neo-Confucian values became more deeply entrenched in the Joseon society, yabok clothing became more popular. By the late Joseon period, even government officials often had yabok portraits painted.

In his comment, Seo Jiksu lamented that the portrait did not fully capture his mind and spirit. In a way, his disappointment affirms that the people of the time believed that a portrait could actually represent a person’s internal essence. Indeed, from the late Joseon period, literati scholars began to evaluate portraits not only on their likeness to the sitter, but also on their expression of his internal mind.

In fact, some literati flatly refused to have their portrait painted, because they doubted the capacity of portraiture to truly capture the spirit. For example, the renowned Neo-Confucian scholar Yun Jeung repudiated the practice of portraiture, but his students secretly had his portrait painted by disguising an artist in literati clothing. Likewise, the scholar Nam Yuyong declined to be painted by the portraitist Bak Seonhaeng, claiming that external appearances were trivial, since a proper Neo-Confucianist should be concerned only with cultivating the mind. Regarding the practice of portraiture, Joseon literati scholars famously believed that, “If even a single hair is not faithfully depicted, then it is not a true portrait of the person.” Thus, in order to earn the trust and approval of the discerning scholars, Joseon portraitists endeavored to capture a person’s likeness as precisely as possible, which inspired them to develop new techniques for more lifelike depictions.

Secrets Hidden in the Portrait

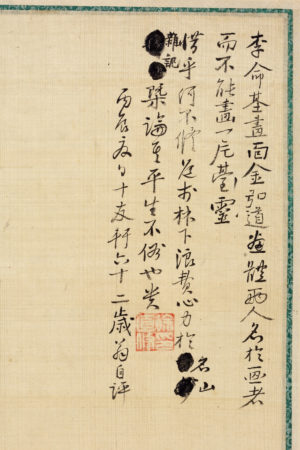

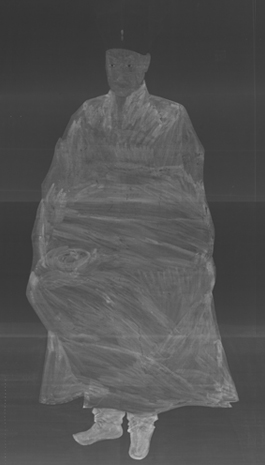

X-ray photograph of Portrait of Seo Jiksu, showing how “reverse coloring” (applying colors to the back of the canvas) was used for added depth.

Portrait of Seo Jiksu is an incredibly vivid depiction of the subject. In particular, the face painted by Yi Myeonggi, the best portraitist of the era, exemplifies the advanced capacity of Joseon portraiture at the time (1796). The facial contours and skin color were rendered with countless short, delicate brushstrokes, each of which was harmoniously blended to convey an expression of astonishing vivacity. Even the smallest details of the face, such as age spots, changes in pigmentation, and wrinkles, were meticulously rendered. In addition, the pointed dongpagwan hat was carefully shaded, making it look like a three-dimensional object.

While our gaze is initially drawn to the face, what about the body painted by Kim Hongdo? To take a closer look at the artists’ techniques, the National Museum of Korea conducted X-ray photographic analysis of this work. Having a shorter wavelength than visible light, X-rays can provide a wealth of information that cannot be seen with the naked eye. The X-ray analysis of Portrait of Seo Jiksu reveals a number of rough strokes covering the body.

What are we to make of these broad strokes that cannot even be seen in the final painting? In fact, as shown by the X-ray photograph, the brushstrokes filling the robe were actually applied to the reverse side of the canvas, a method called “reverse coloring.” With this technique, the pigments seep through the silk threads of the canvas, allowing for more subtle expressions of color. After applying the basic colors of the face and clothes to the reverse side, the details are then rendered in light colors on the front side, for a more elegant depiction of the sitter. For example, as confirmed by the X-ray photograph, Seo’s robe was painted with white on the reverse side, allowing for deeper tones and more refined expressions of color than paintings without reverse coloring.

Looking at Portrait of Seo Jiksu, we feel a tremendous sense of calm. Evincing the spirit of attempting to capture the inherent contradictions and complexities of a human being on a two-dimensional surface, this work inspires new reverence for the people of the past, who believed that a portrait could be a vessel for the mind and spirit, rather than a mere image. The infusion of such faith is what gives Joseon portraiture such remarkable power and dignity.