Raja Ravi Varma, A Galaxy of Musicians, 1889, oil on canvas. 49 x 43 inches (Sri Jayachama Rajendra Art Gallery, Jaganmohan Palace, Mysore, Karnatak)

Map of British India, 1914 (NZ Ministry for Culture and Heritage)

A Galaxy of Musicians, one of Ravi Varma’s most famous paintings, depicts 11 Indian women who appear to be in the midst of an elaborate musical performance. Some sit, others stand. Some hold instruments, others seem to listen. If we look closely at the painting, we can see that Varma also shows each woman wearing different types of dresses and adornments associated with different regions or communities in India. There is a Muslim woman on the right, a Nair caste woman wearing the Nair mundu dress and playing a veena on the left, and a woman at center wearing a Marathi-style saree and green glass bangles typical of Marathi brides. A woman standing in the back row on the left holds a fan and wears a saree with an embroidered border typical of the Parsi community, while the woman next to her dons a dress and feathered hat similar to those which a British or Indo-European woman might wear. Each of the women in Varma’s Galaxy of Musicians not only symbolize the geographic and cultural diversity of India, but also appears to represent idealized forms of femininity and beauty according to the artist: they are young, fair-skinned, attractive, desirable and demure. Only two women in the group (back row, right side) seem to meet the viewer’s gaze; instead, these women are largely unaware of the viewer’s presence and appear as if on display for the visual pleasure of a (presumably male) onlooker.

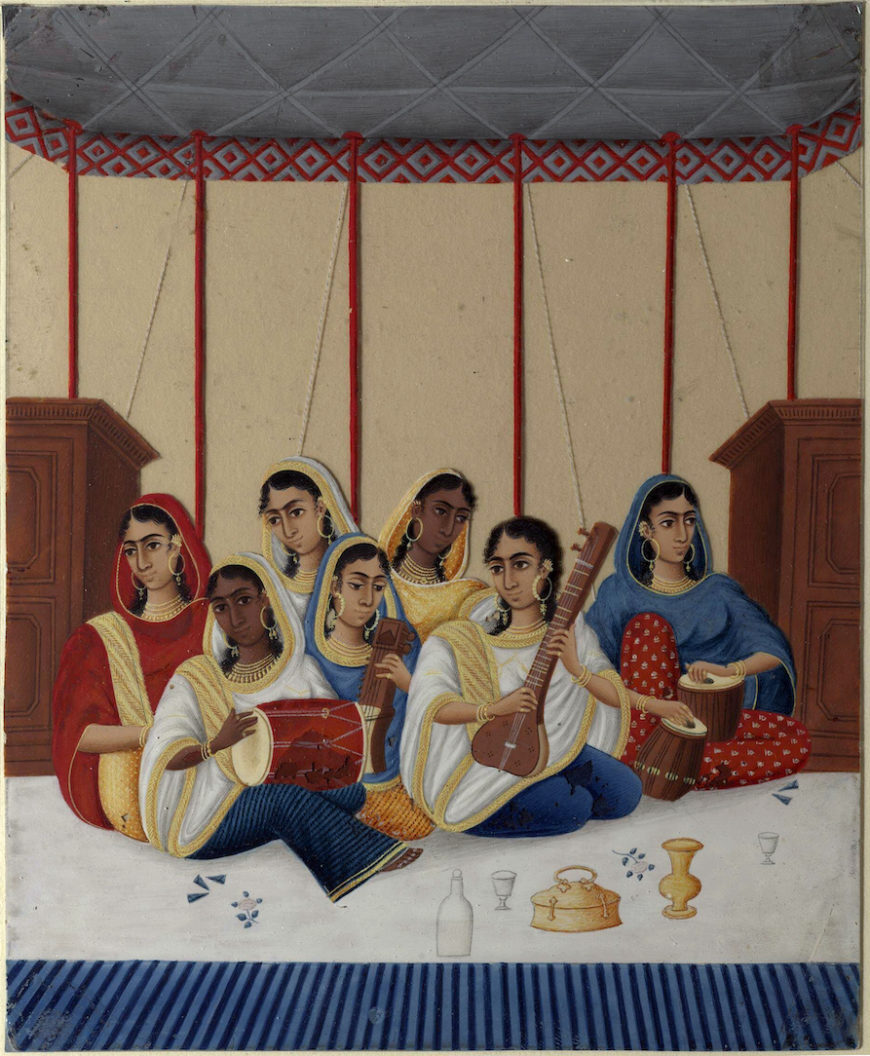

Shiva Lal, A group of seven female musicians seated under a canopy, c. 1865, gouache on mica, Patna, India, 20 16.5 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum)

While Varma’s subject matter of female musicians was not new, his choice of materials and style of rendering the figures were different. Depictions of idealized figures wearing regional dress appear throughout so-called “Company School” paintings, a general term used to describe the diverse artistic output of Indian artists who produced work for British patrons, many of whom were affiliated with the British East India Company in India. One such painting from c. 1865 by the artist Shiva Lal depicts a group of seven female musicians seated underneath a fabric canopy. These musicians appear more like generic “types” rather than individualized portraits: the women have similar faces (even if their skin colors are different) and all appear to wear the same style of dress and jewelry. By contrast, Varma’s musicians in Galaxy seem to flaunt their differences and individuality. Varma shows an array of women from different regions of India as a way to present an image of a unified Indian nation, and to promote Indian nationalism, a difficult task given India’s diversity of ethnicities, regional groups, religions and castes as well as the fact that the country was under British colonial rule at the time.

As Galaxy indicates, art became a force of nationalist expression and artists like Varma played a key role in shaping nationalism across the hierarchy of castes and diversity of regions in India by the end of the nineteenth century. Indian opposition to British colonial rule on the subcontinent had been growing for many years and emerged through both subtle and overt acts of defiance such as peaceful protests, refusing to pay taxes, obfuscation of information, vandalism, and violent insurrections. These efforts occurred in isolated villages as well as through larger, multi-regional cooperation, and formed the basis for rising anticolonial nationalism that was sweeping the country.

In Galaxy, Varma used oil paint which allowed him to depict details of dress, the textures of fabrics and instruments, and the shine and glitter of jewelry with a degree verisimilitude not possible with water-based paints. Oil paint was not used in indigenous Indian painting, but rather was introduced by Europeans living and working on the Subcontinent. Like many artists in late nineteenth-century India, Varma was affected by new cultural and technological changes, such as new materials, like oils and new techniques such as lithography, oleography, and photography. As a child Varma showed artistic talent and moved to the Travancore capital Trivandrum to study art under the patronage of the Maharaja there for whom his uncle worked. There he was introduced to European art in books and met Anglo-Dutch painter Theodore Jensen in 1868 who allowed Varma to watch him paint with oils.

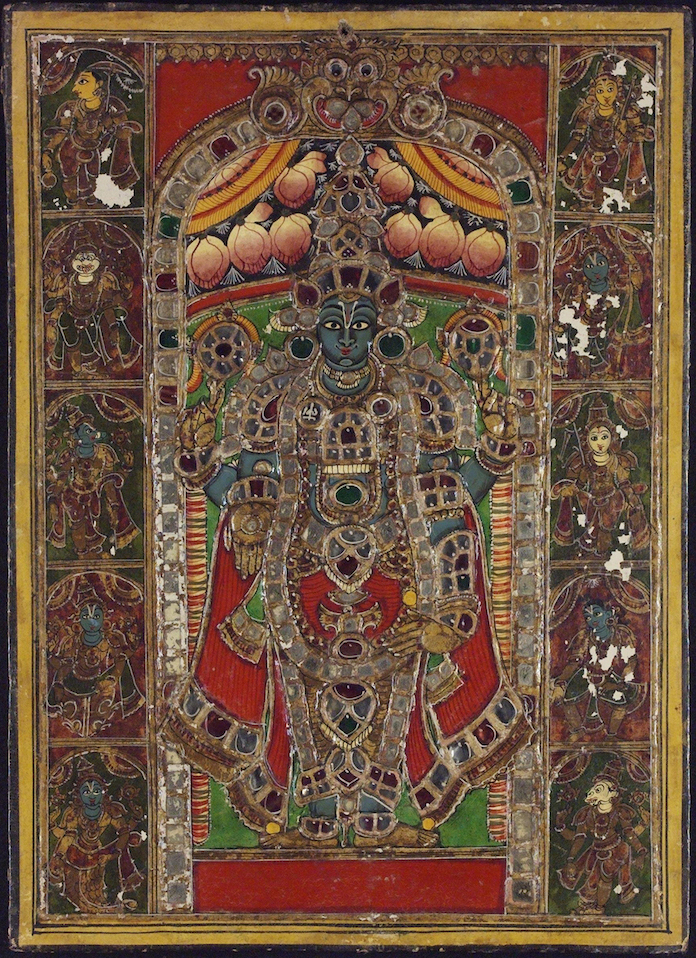

Vishnu, c. 1830–50, gouache painted on wood, with applied pieces of foiled gold, Tanjore, India (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Varma was inspired by Jensen’s painting style which echoed curricula at government-run art schools across the country and which was reflected in reproductions of European visual culture found in wide circulation in India during this time. These art schools promoted oil paint, an illusion of three-dimensionality created through the modulation of light and shadow, and one-point perspective. All of these techniques constructed a European-style realism—the attempt to depict figures and objects in three-dimensions as they appear in life. In addition to drawing inspiration from Jensen’s work, Varma also had an interest in Tanjore (now Thanjavur) painting, an artistic genre that features iconic images of Hindu gods and goddesses rendered with bright colors and rich ornamentation.

Varma’s application of oil painting and realist style, such as we see in Galaxy, is sometimes called “Indian realism.” It is considered his most important contribution to Indian art besides his attempt to represent national unity out of India’s rich cultural diversity.

Raja Ravi Varma, Shakuntala Removing a Thorn from her Foot, 1898, oil on canvas, 181 x 110 cm (Sree Chitra Art Gallery, Thiruvananthapuram; The Ganesh Shivaswamy Foundation, Bengaluru)

Besides Galaxy, Varma applied his “Indian realism” to images of gods and characters from the major Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Using European methods and oil paint, Varma visualized heroic characters from India’s myths and epics and made them more human-like, which was different from earlier depictions of gods and goddesses as otherworldly beings with multiple arms and fantastical characteristics (e.g. Shiva Nataraja or Ganesha). [1] In Shakuntala Removing a Thorn from her Foot, Shakuntala, a character from the Mahabharata, longing to be with her lover King Dushyanta, pretends to remove a thorn from her foot in order to see her lover once more before returning home. Shakuntala’s head and body twist to express her longing, her human emotion, and as scholar Tapati Guha-Thakurta notes, to place her within her story made of “an imagined sequence of images and events.” [2] Representing such figures realistically, Varma moved them from the realm of the gods to the realm of humans, from myth to history. [3]

Due to Varma’s immense popularity and the mass circulation of his compositions as oleographs printed through the Ravi Varma Press, his invented images became the prominent view of religious subjects. [4] Varma’s subjects—both his idealized, diverse figures in Galaxy and the humanized gods and mythic characters of his oil paintings and prints—became interpreted as a nostalgia for an imagined Hindu past before the period of British colonial rule (c. 1757–1947) , while also expressing India’s nascent anticolonial nationalism.

Modern master or master of kitsch?

Varma has been identified with European academic art (an art of detailed realism, such as Jensen’s paintings), Indian modernism tied to nationalism, popular kitsch, and a Romantic style. [5] With the wide circulation and mass appeal of Varma’s images as inexpensive prints, his art became synonymous with popular culture and consumerism and moved away from being exclusively associated with a realm of “fine art.” Moreover, Varma’s compositions created depictions of his subjects that connected with aesthetic trends found in Romanticism or a Romantic style, namely beautiful, idealized figures that conveyed emotional intensity and wild natural spaces that recall the aesthetics of the Sublime.

He was contradictorily seen as both modern and populist, that is, simultaneously as an innovative avant-garde artist while at the same time catering to popular trends. His identity as a modernist was contested by the modern Bengal School artists (such as Abanindranath Tagore) who attacked his Westernization and instead drew artistic inspiration from styles considered to be indigenous to India such as Mughal painting and the murals at Ajanta.

Varma’s art asks us to challenge many preconceived art historical ideas. Modernism, once defined as revolutionary art focusing on abstract form without narrative, is now recognized as a flexible term depending on the country whose modernism is studied. Kitsch is no longer considered degraded, “low brow,” or reduced to storytelling, but is now taken seriously as a cultural force. Varma’s art at different periods in history fit both of these terms.

Both today and during his lifetime, Varma held multiple, sometimes contradictory roles. The retrospective of Varma’s work at the National Museum in New Delhi in 1993 provoked debates over the artist’s legacy within the history of Indian modernism, while his popularity remains unabated. Although not the first artist to use Western style to represent Indian myths, his works’ popularity and wide dissemination made his images the most prominent ones of these subjects. In 1904 the British India government (also known as the British Raj) awarded him its highest honor, the Kaiser-i-Hind award, while Varma was also feted by the Indian National Congress for contributing to nation-building and to a movement for ending British control of India.

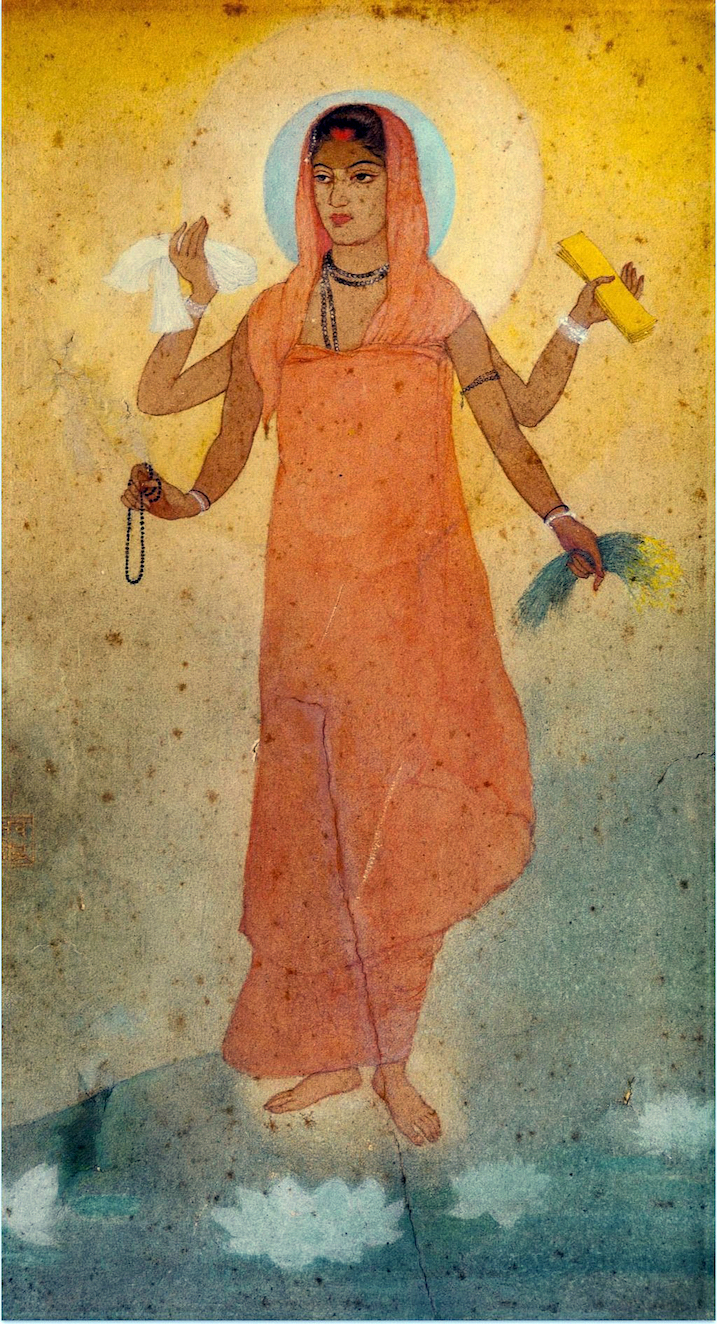

Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata, 1905, gouache, 26.6 x 15.2 cm (Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata, India)

While the subject matter of Galaxy of Musicians is not explicitly religious, the women in the painting appear very much like the goddesses that grace Varma’s other compositions. As a subject, they bring to mind the female beauties and attending musicians that appear on the exterior of many Hindu temples, creating an auspicious and celebratory environment for the gods or goddesses revered inside. In some ways, Varma’s Galaxy of Musicians perform for and attend to the idea of a nation as if it is a divine, life-giving force, and in doing so become embodiments of the nation itself, much like the goddess Bharat Mata, who visualizes the unification of the country through her body. India—conceptualized as a unified whole—becomes the center of this galaxy, surrounded by the female bodies that Varma uses to imagine it into being.