Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha)

Maybe you can bring it with you…if you are rich enough. The elite men and women of the Han dynasty enjoyed an opulent lifestyle that could stretch into the afterlife. Today, the well-furnished tombs of the elite give us a glimpse of the luxurious goods they treasured and enjoyed. For instance, a wealthy official could afford beautiful silk robes in contrast to the homespun or paper garments of a laborer or peasant. Their tombs also inform us about their cosmological beliefs.

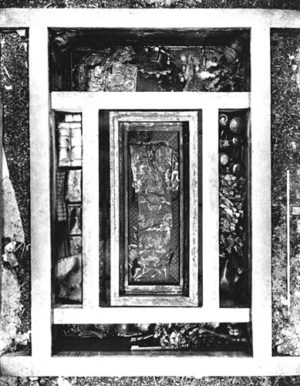

Nesting coffins of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., wood, lacquered exteriors and interiors, 256 x 118 x 114 cm, 230 x 92 x 89 cm, and 202 x 69 x 63 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha)

Marquis of Dai, Lady Dai, and a son

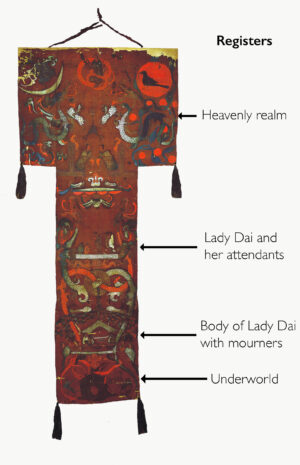

Diagram of Funeral Banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha)

Three elite tombs, discovered in 1972, at Mawangdui, Hunan Province (eastern China) rank amongst the greatest archeological discoveries in China during the 20th century. They are the tombs of a high-ranking Han official civil servant, the Marquis of Dai, Lady Dai (his wife), and their son. The Marquis died in 186 B.C.E., and his wife and son both died by 163 B.C.E. The Marquis’ tomb was not in good condition when it was discovered. However, the objects in the son’s and wife’s tombs were of extraordinary quality and very well preserved. From these objects, we can see that Lady Dai and her son were to spend the afterlife in sumptuous comfort.

In Lady Dai’s tomb, archaeologists found a painted silk banner over six feet long in excellent condition. The T-shaped banner was on top of the innermost of four nesting coffins. Although scholars still debate the function of these banners, we know they had some connection with the afterlife. They may be “name banners” used to identify the dead during the mourning ceremonies, or they may have been burial shrouds intended to aid the soul in its passage to the afterlife. Lady Dai’s banner is important for two primary reasons. It is an early example of pictorial (representing naturalistic scenes, not just abstract shapes) art in China. Secondly, the banner features the earliest known portrait in Chinese painting.

We can divide Lady Dai’s banner into four horizontal registers. In the lower central register, we see Lady Dai in an embroidered silk robe leaning on a staff. This remarkable portrait of Lady Dai is the earliest example of a painted portrait of a specific individual in China. She stands on a platform along with her servants–two in front and three behind.

Left: Lady Dai and her attendants (detail), Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm; right: Lady Dai and her attendants (detail), Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha)

Long, sinuous dragons frame the scene on either side, and their white and pink bodies loop through a bi (a disc with a hole thought to represent the sky) underneath Lady Dai. We understand that this is not a portrait of Lady Dai in her former life, but an image of her in the afterlife enjoying the immortal comforts of her tomb as she ascends toward the heavens.

Body of Lady Dai with mourners (detail), Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha)

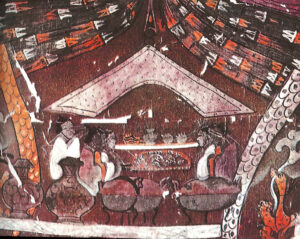

In the register below the scene of Lady Dai, we see sacrificial funerary rituals taking place in a mourning hall. Tripod containers and vase-shaped vessels for offering food and wine stand in the foreground. In the middle ground, seated mourners line up in two rows. Look for the mound in the center, between the two rows of mourners. If you look closely, you can see the patterns on the silk that match the robe Lady Dai wears in the scene above. Her corpse is wrapped in her finest robe! More vessels appear on a shelf in the background.

In the mourning scene, we can also appreciate the importance of Lady Dai’s banner for understanding how artists began to represent depth and space in early Chinese painting. They made efforts to indicate depth through the use of the overlapping bodies of the mourners. They also made objects in the foreground larger, and objects in the background smaller, to create the illusion of space in the mourning hall.

The afterlife in Han dynasty China

Lady Dai’s banner gives us some insight into cosmological beliefs and funeral practices of Han dynasty China. Above and below the scenes of Lady Dai and the mourning hall, we see images of heaven and the underworld. Toward the top, near the cross of the “T,” two men face each other and guard the gate to the heavenly realm. Directly above the two men, at the very top of the banner, we see a deity with a human head and a dragon body.

Heavenly realm (detail), Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha)

Wooden outer coffin within the central coffin chamber surrounded by four side boxes, tomb 1,672 x 488 x 280 cm

On the left, a toad standing on a crescent moon flanks the dragon/human deity. On the right, we see what may be a three-legged crow within a pink sun. The moon and the sun are emblematic of a supernatural realm above the human world. Dragons and other immortal beings populate the sky. In the lower register, beneath the mourning hall, we see the underworld populated by two giant black fish, a red snake, a pair of blue goats, and an unidentified earthly deity. The deity appears to hold up the floor of the mourning hall, while the two fish cross to form a circle beneath him. The beings in the underworld symbolize water and earth, and they indicate an underground domain below the human world.

Four compartments surrounded Lady Dai’s central tomb, and they offer some sense of the life she was expected to lead in the afterlife. The top compartment represented a room where Lady Dai was supposed to sit while having her meal. In this compartment, researchers found cushions, an armrest, and her walking stick. The compartment also contained a meal laid out for her to eat in the afterlife. Lady Dai was 50 years old when she died, but her lavish tomb—marked by her funeral banner—ensured that she would enjoy the comforts of her earthly life for eternity.

This essay was written with the assistance of Dr. Wu Hung.