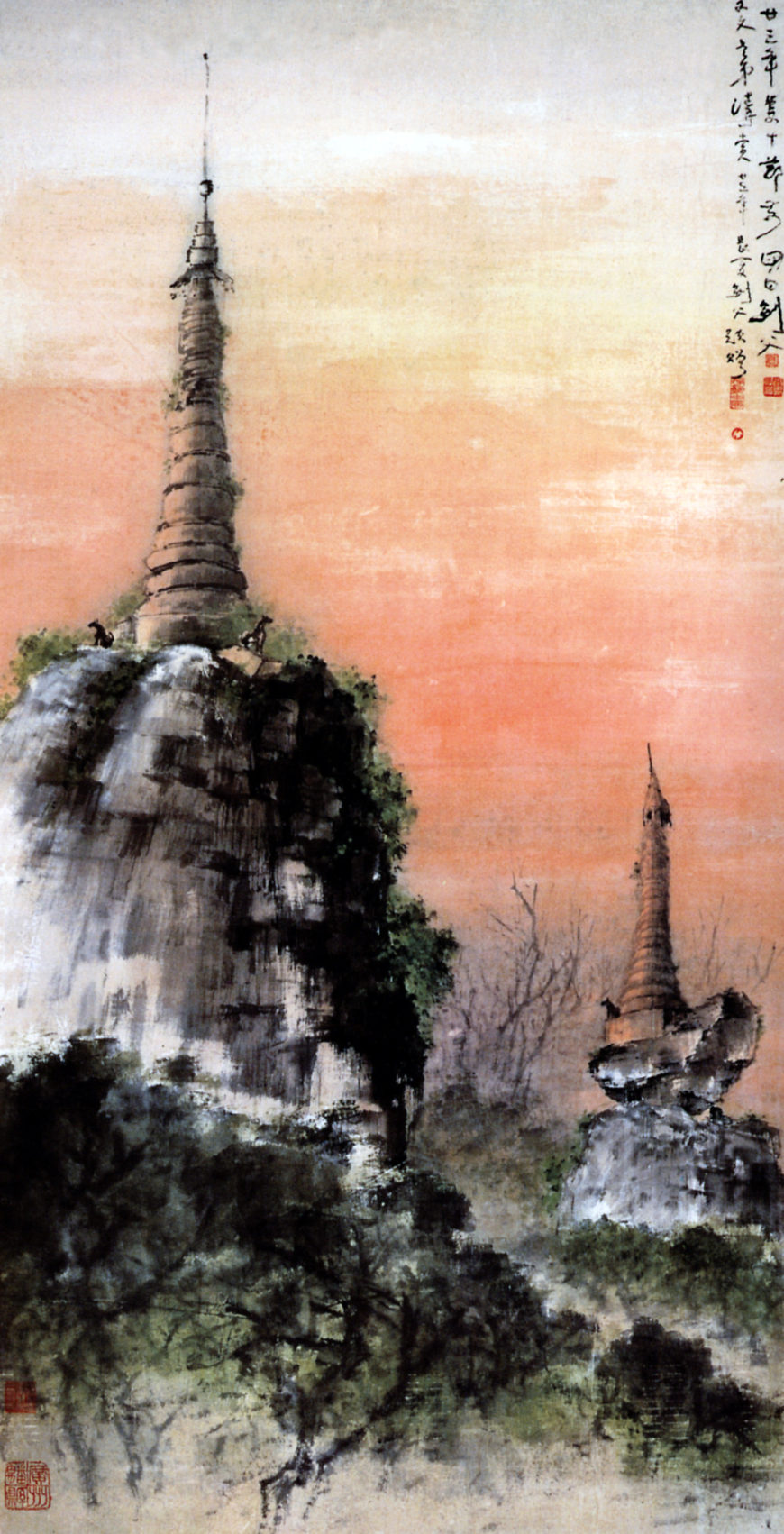

Gao Jianfu (高劍父), Flying in the Rain, 1932, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), China, 46 x 35.5 cm (Hong Kong, Art Gallery, Chinese University of Hong Kong)

At first glance, the landscape elements of Flying in the Rain appear like many Chinese paintings: low-lying sandbars and distant mountains, with a Buddhist pagoda emerging from the haze. However, an earthy brown wash and splashes of ink lend an ominous tone to the scene, one that evokes the marshy southern landscape of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers, to which emperors often banished unruly court officials and scholars. Poets throughout the past millennium described this legendary landscape in their laments. As early as the eleventh century, artists composed the landscape in eight views, one of which portrayed geese descending on the sandbar—a metaphor for the exiled scholar.

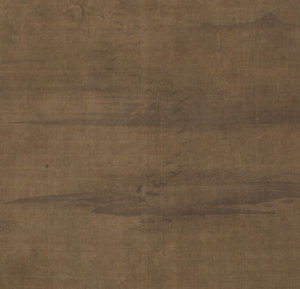

Wang Hong, Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers, Southern Song Dynasty, c. 1150, pair of handscrolls, ink and light colors on silk, each section: approximately 23.6 x 87.5 cm (Princeton University Art Museum)

Detail of geese descending. Wang Hong, Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers, Southern Song Dynasty, c. 1150, pair of handscrolls, ink and light colors on silk, each section: approximately 23.6 x 87.5 cm (Princeton University Art Museum)

In Flying in the Rain, however, Gao Jianfu pictured a squadron of biplanes emerging from cloudy skies in loose formation, alluding to the melancholy image of geese descending in imperial times (such as Wang Hong’s painting from the Song dynasty). Planes were an uncommon sight in China—a mark of modern technology and warfare.

When Gao’s painting was created, Imperial Japanese troops had just seized Manchuria (in 1931), and China’s ruling party (the Nationalist Party, KMT or GMD, or Guomindang 國民黨) struggled to defend against this growing threat to the nation. Motivated by a deep sense of patriotism, Gao Jianfu offered a bold approach to the synthesis of Chinese and European traditions at a time when many questioned the future of the ancient tradition of Chinese ink painting—believing that it could not address the demands of the modern world.

The Lingnan School

An example of nihonga. Yokoyama Taikan, Snowy Peak with Cranes, 1958 (Yokoyama Taikan Memorial Museum, Tokyo)

Based in the coastal city of Guangdong, near Hong Kong and the Cantonese-speaking region of China, the artist Gao Jianfu (along with his brother Gao Qifeng and Chen Shuren) launched a modern movement to revive Chinese painting due to concerns about the relevance of traditional Chinese painting in modern times. Gao Jianfu had gone abroad to study in Japan, where he was inspired by the Japanese movement to revive their traditional painting, called nihonga, by introducing Western techniques such as shading, modeling, and contemporary subject matter. The two brothers, along with several other loosely associated artists active in the Lingnan region, or “south of the Southern Mountains,” became known as the Lingnan school.

Artists of the Lingnan school sought to advance traditional Chinese ink painting by using Chinese brushwork in water and ink, often in the context of traditional formats of hanging scrolls or handscrolls. The Lingnan school certainly was not the only group of artists working in this mode. Artists of the Shanghai school, for instance, also worked in the traditional ink painting mode and occupied a more dominant role in the landscape of Chinese art. However, Lingnan school artists were unique in their experiments in color, volume, and other aspects associated with European art. Rather than adopt the medium and techniques of European oil painting to reform Chinese painting, artists like Gao Jianfu and the Lingnan school aimed to revive Chinese ink painting.

Reviving guohua

Although many of his contemporaries argued that traditional Chinese painting could not address the demands of modernity, Gao Jianfu sought to revive Chinese painting, or guohua (national painting) as a national art form. Having studied the synthesis of Japanese and European painting techniques to create a distinctive national style, Gao returned to China to participate in the broader movement of reviving guohua during the 1930s.

Moved by the New Culture Movement of the 1910s and 1920s, which promoted a modern Chinese culture based on progressive Western ideals, he launched a magazine that brought reproductions of artworks to a public audience. He was appointed by Sun Yatsen to lead the provincial art school in Guangdong province, and became closely aligned with the Minister of Education, Cai Yuanpei, who was a great proponent of art education. Cai felt that aesthetic education could cultivate a sense of mission about the salvation of the nation, and recognized Gao’s commitment to the patriotic cause.

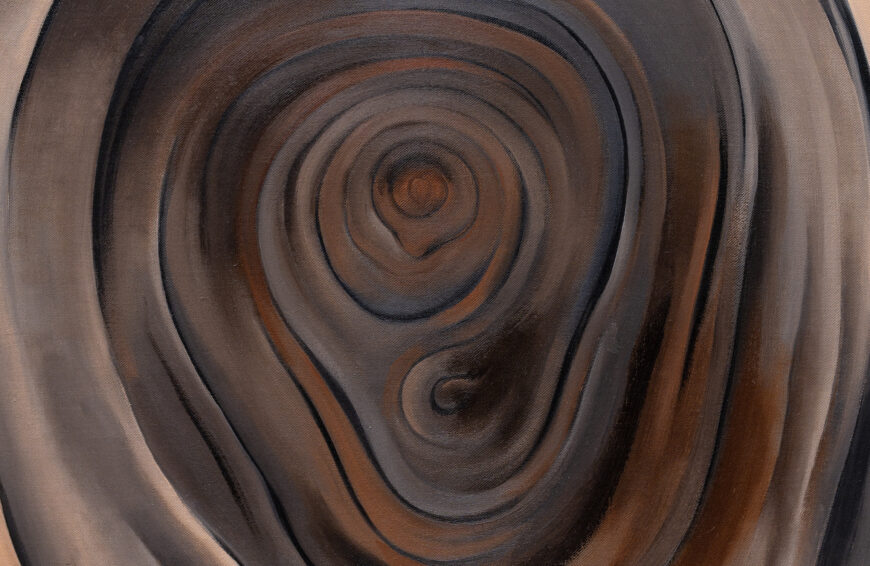

Gao Jianfu, Flying in the Rain (detail), 1932, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), China, 46 x 35.5 cm (Hong Kong, Art Gallery, Chinese University of Hong Kong)

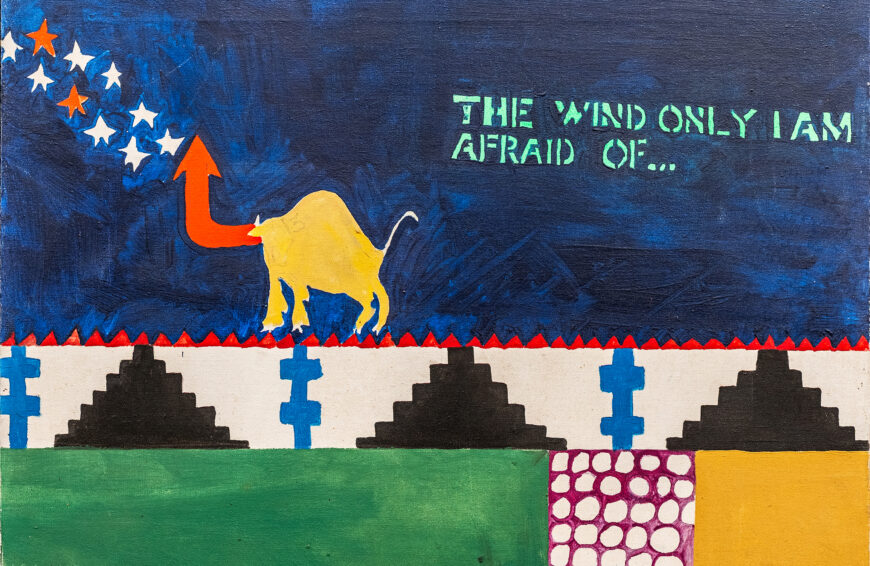

Gao Jianfu believed that he could popularize art as a national language by adapting traditional themes with modern subject matter like tanks and airplanes, as in Flying in the Rain. His images conveyed the conflicts between old and new, often with themes of grief and loss that characterized his own love for his country.

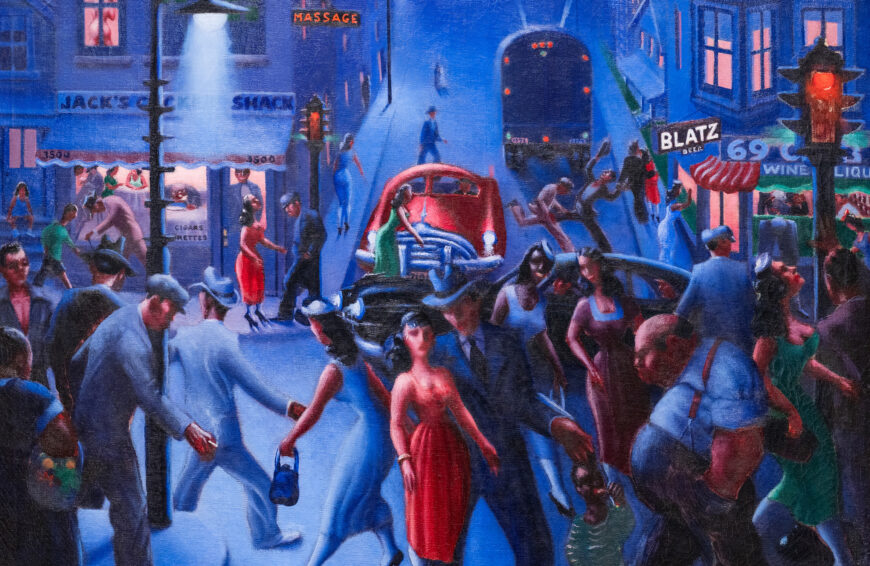

Gao Jianfu, Stupa Remains in Burma, 1934, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), 162 x 84 cm (The Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong)

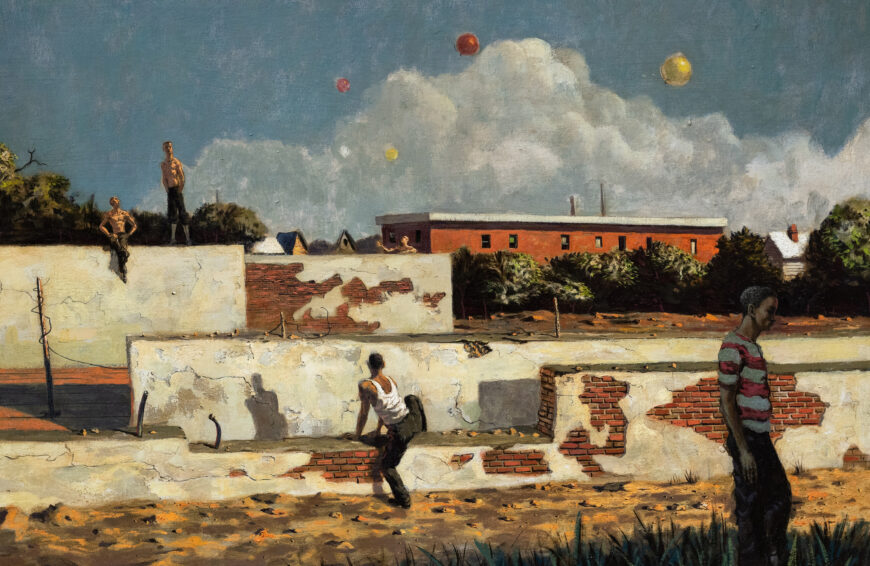

Works by Gao Jianfu often synthesized Western techniques such as the modeling of forms, as in Stupa Remains in Burma, which portrays two decaying Buddhist stupas in the golden pink hues of dusk. Here, the light of the setting sun appears to reflect off the left side of the stupas, while the right sides are darkened in shadow, giving a sense of volume and weight to their circular forms. This scene of ruins, from the stone animals guarding the cardinal directions of each stupa to the precarious perch of each stupa atop crumbling rockery, appears desolate and forgotten with no signs of movement. Gao, himself a Buddhist, had traveled extensively through India, Burma (Myanmar), and the Himalayas where he undoubtedly drew inspiration for this work.

Gao Jianfu, Flying in the Rain, 1932, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), China, 46 x 35.5 cm (Hong Kong, Art Gallery, Chinese University of Hong Kong)

Conveying a sense of melancholy and loss like that of Flying in the Rain, Gao noted in his inscription that he painted the work four days before the Double Ten Festival in the 23rd year of the Republic of China. Double Ten Festival is celebrated on the tenth day of the tenth month, marking the day that Sun Yatsen’s revolutionary army overthrew the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty and founded the Republic in 1911. This revolution, the Xinhai Revolution, brought an end to China’s long imperial history of dynasties ruled by emperors. The holiday is still celebrated in Taiwan today as National Day because the National Party retreated to Taiwan in 1949 when the Chinese Communist Party gained control of the mainland. Whether picturing modern warfare or landscapes of ruins, Gao’s images coupled sentiments of tragedy and despair with a rallying urgency to revive ink painting as a national art form.

A critical moment in modern Chinese art

With works like Flying in the Rain, Gao Jianfu inspired many artists, most directly those of the Lingnan School, in championing a revival of a national-style painting. Having studied abroad and traveled extensively, Gao offered a unique solution to ink painting in Republican China. Many of his contemporaries had not seen modern airplanes or tanks, or Japanese nihonga or Western oil paintings; in fact, many Chinese had seen few if any ink paintings because they generally were held in imperial or private collections. Although his pictorial style did not match the lasting impact of Shanghai School artists, it was Gao’s efforts to expand the role of art in society that represent a critical moment in the trajectory of art in modern China.