Portrait of Sin Sukju, second half of the 15th century, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 167 x 109.5 cm, Goryeong Sin Family Collection, Cheongwon, Treasure no. 613.

Portrait paintings commemorated the sitter in both life and death in Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) Korea. This painting depicts Sin Sukju (1417–75) as a “meritorious subject,” or an official honored for his distinguished service at court and loyalty to the king during a tumultuous time. Skilled in capturing the likeness of the sitter while still adhering to pictorial conventions, artists in the Royal Bureau of Painting (a government agency staffed with artists) created portraits of officials awarded this honorary title. These paintings would be cherished by their families and worshiped for generations to follow.

A meritorious portrait

This painting shows Sin Sukju dressed in his official robes with a black silk hat on his head. In accordance with Korean portraiture conventions, court artists pictured subjects like Sin Sukju seated in a full-length view, often with their heads turned slightly and only one ear showing. Crisp, angular lines and subtle gradations of color characterize the folds of his gown. Here, the subject is seated in a folding chair with cabriole-style arms, where the upper part is convex and the bottom part is concave. Leather shoes adorn his feet, which rest on an intricately carved wooden footstool. In proper decorum, his hands are folded neatly and concealed within his sleeves. He wears a rank badge on his chest.

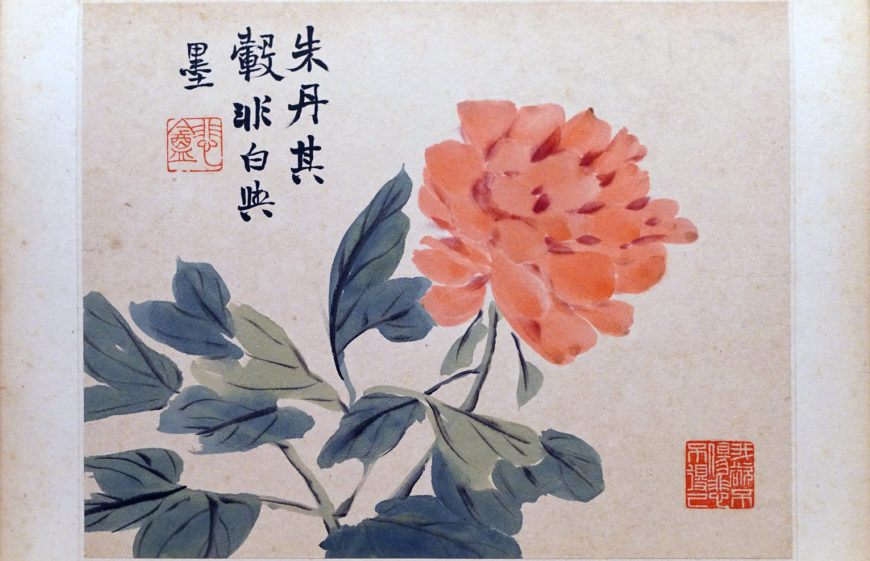

Rank badges are insignia typically made of embroidered silk. They indicate the status of the official, which could be anyone from the emperor down to a local official. As in Ming-dynasty China (1368–1644), images of birds on rank badges precisely identified the rank of the wearer. Here, Sin Sukju’s rank badge shows a pair of peacocks amongst flowering plants and clouds. It is an auspicious scene suiting a civic official, and especially luminous with the use of gold embroidery. Crafted in sets, rank badges were worn on both the front and back of the official overcoat.

Physical likeness

Although portraiture conventions, such as the attire and posture of the sitter, were quite formulaic, the facial features were painted with the goal of transmitting a sense of unique, physical likeness. This careful attention to the sitter’s face, such as wrinkles and bone structure, served the Korean belief that the face could reveal important clues about the subject.

Portrait of Sin Sukju (detail), second half of the 15th century, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 167 x 109.5 cm, Goryeong Sin Family Collection, Cheongwon, Treasure no. 613.

Look carefully and you might notice the wrinkles around the edges of Sin Sukju’s eyes (“crow’s feet”). His thin, almond-shaped eyes are bright and clear, and his mouth is surrounded by deep grooves where his moustache meets his chin. His solemn visage exudes wisdom and dignity.

The meticulous brushwork on Sin Sukju’s face is even more striking in comparison with the solid, undulating lines and bold blocks of color that define his attire. Highly skilled artists at the court may have collaborated on portraits, such that one artist may have painted the robes according to the prescribed rank or title, while another may have painted the face in great detail. Later portraits developed this interest in the face even further with the use of Western painting techniques introduced to Korea by Jesuit missionaries in China in the eighteenth century.

Portrait of Sin Sukju (detail), second half of the 15th century, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 167 x 109.5 cm, Goryeong Sin Family Collection, Cheongwon, Treasure no. 613.

Sin Sukju and Hwagi

Sin Sukju was an eminent scholar and a powerful politician who rose to the rank of Prime Minister. Named a meritorious subject four times in his life, he served both King Sejong and King Sejo. Remarkably, he managed to maintain court favor through the tumult of King Sejo’s coup in 1453. In the course of capturing the throne, King Sejo arrested and killed his own brother, Prince Anpyeong, who Sin Sukju had also served until the prince’s untimely death.

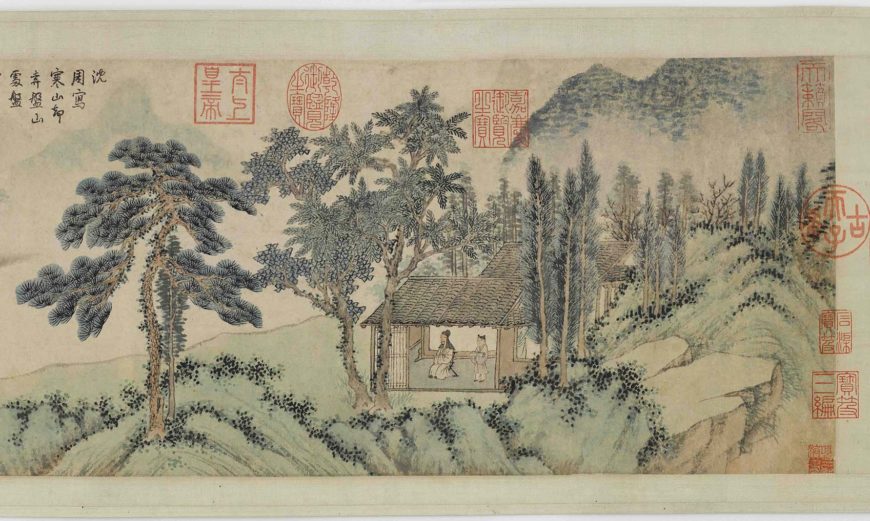

It was his service to Prince Anpyeong that earned Sin Sukju a significant place in the history of art. In 1445, Sin Sukju compiled Hwagi (Commentaries on Painting), which contains a catalogue of Prince Anpyeong’s collection of paintings. Sin Sukju’s detailed records revealed the prince’s interest in Chinese paintings and his patronage of the Joseon court painter, An Gyeon, who was professionally active as an artist for 30 years beginning in approximately 1440. Sin Sukju’s commentaries have helped scholars to identify specific works and prompted speculation on the cultural exchange between China and Korea.

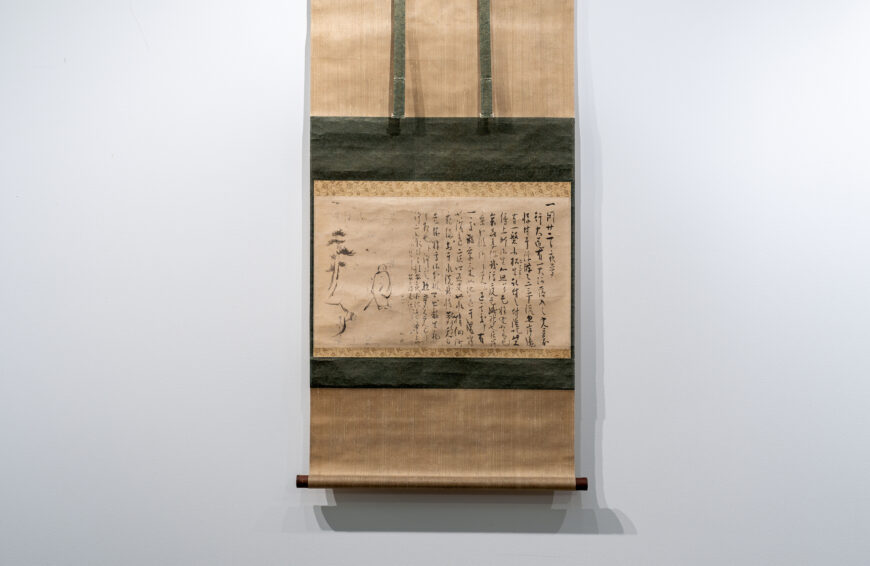

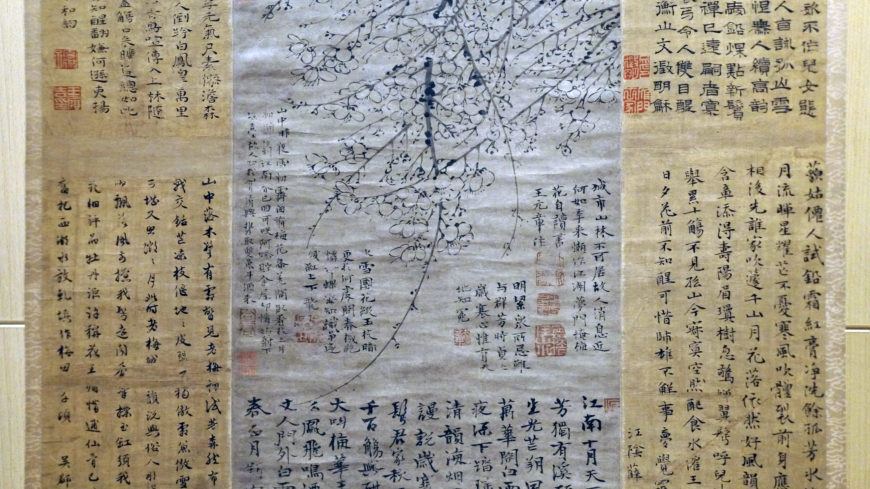

An Gyeon, Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land, 1447, handscroll with ink and light color on silk, 38.6 x 106.2 cm, Tenri Central Library, Tenri University, Nara, Japan

Ancestral worship

In addition to the virtue of loyalty (such as the devotion of a subject to his ruler), Confucianism emphasized filial piety, or honor and respect for one’s elders and ancestors. Even more important than recording the sitter’s appearance and preserving his rank during life, portrait painting served as a focus for ancestral rituals after his death. It was thought that when a person died, the soul of the deceased remained among the world of the living until it gradually dissipated. Rendered in the format of a hanging scroll, this painting likely hung within the family shrine to guide the soul in the practice of ancestral worship. In this way, Portrait of Sin Sukju reflected both the honor that Sin Sukju brought to his lineage as a meritorious official as well as Confucian beliefs about the afterlife.