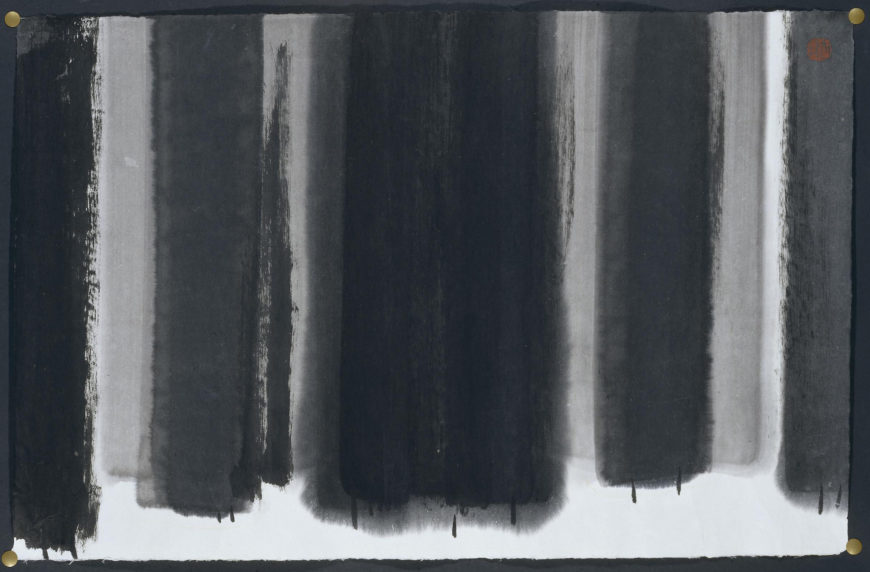

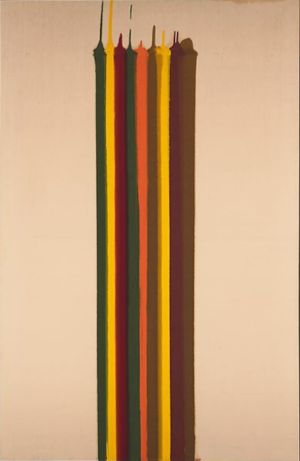

Song Su-Nam, Summer Trees, 1979, ink on paper, 2 feet 1-5/8 inches high (© Trustees of the British Museum) © Song Su-Nam

Modern, but deeply rooted in tradition

In Song Su-nam’s Summer Trees, broad, vertical parallel brush strokes of ink blend and bleed from one to the other in a stark palette of velvety blacks and diluted grays. The feathery edges of some reveal them to be pale washes applied to very wet paper, while the darkest appear as streaks that show both ink and paper were nearly dry. The forms overlap and stop just short of the bottom edge of the paper, suggesting a sense of shallow space—though one that would be difficult to enter. Only a practiced hand could control ink with such simplicity and impact. The painting exudes psychological power, despite its relatively modest proportions (it is only a little more than 2 feet high).

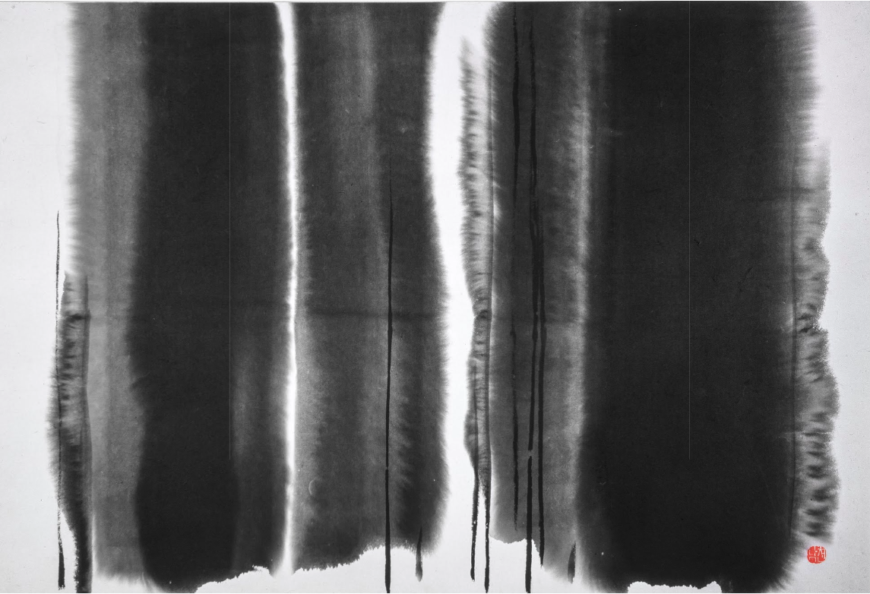

Song’s exploration of tone (the shades of black and gray) and the effects produced by the marks of the brush, the wet paper, and dripping ink, has led some to think that these abstract, formal qualities are the real subject of this very modern-looking work. But it is important that the title refers to the natural world. Song created Summer Trees in 1979, but he made at least two similar paintings. One, in 1985, he called Tree. Not until the second, painted in 2000, did he fully embrace abstraction. His title—and even his decision to create a work in ink—shows us that though clearly addressing issues of contemporary art—Song’s work is deeply rooted in tradition.

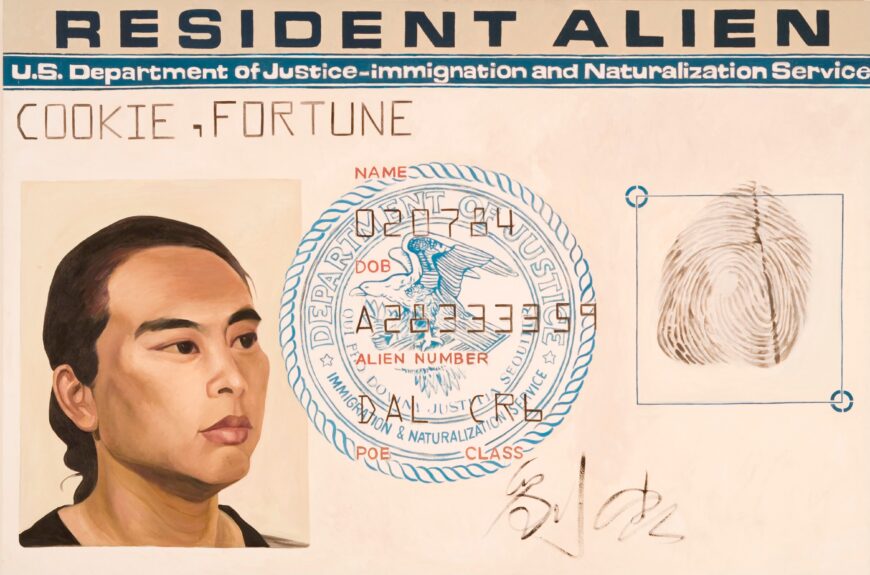

Song Su-Nam, Tree, 1985, ink on paper, 94 x 138 cm (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea) © Song Su-Nam

Ni Zan, Six Gentlemen, 1345, hanging scroll, ink on paper, 61.9 x 33.3 cm (Shanghai Museum; photo: Difference engine)

To choose the medium of ink on paper was important for the artist‚ a leader of Korea’s Sumukhwa or Oriental Ink Movement of the 1980s. Sumukwha is the Korean pronunciation of the Chinese word for “ink wash painting,” also called “literati painting.” The “literatus” can be defined as a “scholar-poet” or “scholar-artist,” a type of ideal man that emerged in China in the 11th century or before. Chinese poetry was considered the noblest art, and “ink wash painting” was its twin, because writing a poem and making a painting used the same tools and techniques—one resulting in words, the other a picture. In their simplicity and reductiveness, the style of ink wash paintings created centuries ago often seem to match Western notions of abstraction.

In Chinese poetry, mountainous landscapes and the plants that grow in them serve as metaphors for the ideal qualities of the literatus himself—qualities such as loyalty, intelligence, spirituality, and strength in adversity. The world the literatus wants to live in is one of beauty, deep in nature, away from the centers of power and money. These themes provided painters with a library of motifs. From the 1970s–90s, Song created many such landscapes, executed unconventionally, with and without titles. Summer Trees may also reference a traditional theme: a group of pine trees can symbolize a gathering of friends of upright character. Whatever his intention with this title, Song was clearly alluding to the special world of the literati. Highly educated and a respected professor, he stood among the modern literati of Korea.

Song’s interest in abstraction and the formal properties of ink has led some art historians to attribute the inspiration for his work to that of American artists like Morris Louis, who used the medium of acrylic resin on canvas in his “Stripe” paintings of the 1960s, which resemble Song’s works of later decades such as Summer Trees. But in Korea during the 1980s, there was a tension between the influence of Western art that used oil paint (whether traditional or contemporary in style), and traditional Korean art that used an East Asian style, the vocabulary of traditional motifs, and the medium of ink for calligraphy and painting. Song felt very strongly that the materials and styles of Western art did not express his identity as a Korean.

Morris Louis, Pungent Distances, 1961, Magna on canvas, 231.8 x 150.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © 1961 Morris Louis

Sumukwha provided Song and his circle with a way to express Korean identity. Since antiquity, the country had taken great pride in a political and cultural distinctiveness that was recognized throughout Asia. Yet the twentieth century had brought trauma: the end of Korea’s ancient monarchy, colonization by the Japanese who had attempted to obliterate the Korean language, mass destruction during the Korean War (1950–53), and the partitioning of the nation. In South Korea, where Song lived, the country was healing but endured authoritarian government and student unrest. People lived in constant fear of hostility from North Korea. For protection, they accepted a conspicuous American military presence, but this cast modernization in a decidedly Westernized light.

Sumukwha’s ideal—the literatus—presented a compelling antidote to the psychological displacement felt by Song’s circle of artists and intellectuals: a model individual of character and moral compass no matter what challenges life presents; and a way of expressing those ideals through his iconic tools of ink and brush. Summer Trees, with its allusions to friendship and a balmy season, could be Song’s statement of optimism in the rediscovery of traditional values recast for modern times.