A calm before a storm

In his painting Samson and Delilah, Anthony van Dyck presents a moment filled with tension—a calm before a storm. Instead of depicting the climax of this Old Testament story, he represented the moment immediately before the action takes place. The heroic Samson is about to have his hair cut—removing the source of his superhuman strength. Lulled to sleep by his lover Delilah, the Philistine guards lie in wait ready to capture and imprison him as soon as the deed is done.

Anthony van Dyck, Samson and Delilah, c. 1618-20, oil on canvas, 152.3 x 232 cm. (Dulwich Picture Gallery, London)

In Van Dyck’s scene, however, the focus is not the hero—Samson—but Delilah. The light within the painting is focused on her, while the edges of the canvas recede into darkness. She is shown bejewelled and in a state of undress, draped in luxurious silk and lounging on a bed covered with rich, brocaded fabric. Delilah’s soft and milky-white skin is in complete contrast to the swarthy Samson, who is covered with only a fur loincloth. All the action within the scene appears to rest on her as she raises a silencing finger, both to hush the guards and to command them into action.

The two women behind Delilah look on with interest and apprehension, waiting to see whether Samson will wake from his slumber. The guards, too, watch with anxiety, knowing that even their combined strength would be no match for the superhuman Samson. Van Dyck heightens the drama further by giving the barber what appear to be giant sheep shears, when normal scissors would do the same job.

Van Dyck and Rubens

Samson and Delilah was painted early in Van Dyck’s career, around 1618-21. During this time, Van Dyck was active in the Antwerp studio of the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, 22 years his senior. It is not known exactly when or under what terms Van Dyck entered Rubens’ studio, whether he was a pupil (or student) or rather an associate, contracted to work on specific commissions. In any case, Rubens had a definite impact upon Van Dyck’s work, revealed most clearly through Samson and Delilah.

Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, c. 1609-1610, oil on panel, 185 x 205 cm. (The National Gallery, London)

Samson and Delilah appears to be a response to Rubens earlier version of the same subject (above). Van Dyck takes a number of elements directly from Rubens—most notably the composition: the side-on-view, with the muscular Samson slumped in a heap on Delilah’s lap. However, Van Dyck reverses the grouping, perhaps indicating that he based his own painting on prints after the painting—where the composition is always reversed—rather than the original.

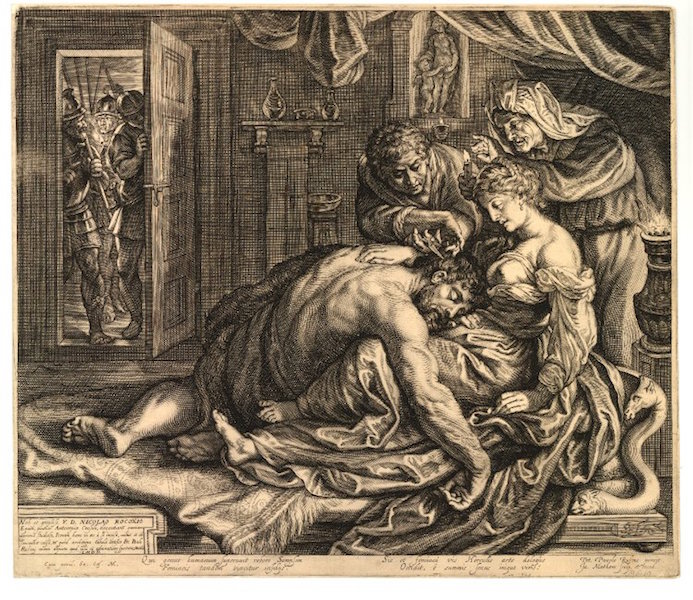

Jacob Maltham (printmaker), after Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, c. 1612, engraving (The British Museum, London)

Van Dyck also borrows from Rubens in more stylistic terms, for example, in the portrayal of flesh and musculature. This is particularly evident in Delilah’s décolletage and Samson’s muscled back. A fascination with textures and textiles is shared by both Rubens and Van Dyck, and the gold-brocaded fabric appears to have been a studio prop, appearing in other paintings by both Rubens and Van Dyck, including Rubens’ St. Ambrose and the Emperor Theodosius (Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna) and Van Dyck’s The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria (Museo del Prado, Madrid).

Greater drama

Yet, Van Dyck’s Samson and Delilah also departs from Rubens’ model in a number of important ways and, as such, can be considered a challenge to the master’s example with Van Dyck asserting his position as the foremost painter of his generation.

Left: Detail, Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, c. 1609-1610, oil on panel, 185 x 205 cm. (The National Gallery, London); right: detail, Anthony van Dyck, Samson and Delilah, c. 1618-20, oil on canvas, 152.3 x 232 cm. (Dulwich Picture Gallery, London)

Rubens sets his version of the story in a bed chamber at night. In complete contrast, Van Dyck chooses to set his scene outside and in bright daylight. Van Dyck’s decision to depict the moment before Samson’s hair is cut is also an important divergence, since in Rubens’ painting the action is already underway. Van Dyck’s aim is seemingly to exploit this moment of tension to create a greater sense of drama within the picture. Van Dyck gives greater agency to the figure of Delilah who, with her raised finger, orchestrates the entire company of characters. Within this context, he is also able to include the exaggerated and theatrical reactions of the supporting cast—especially that of the younger woman who stands behind Delilah. This was evidently something Van Dyck gave considerable thought to and to which he returned at various stages during the course of painting, as evidenced by an X-ray of the work (below), which shows that Van Dyck adjusted the fingers of the woman, splaying them out further so as to create a more dramatic silhouette against the blue sky.

X-ray, Anthony van Dyck, Samson and Delilah, c. 1618-20, oil on canvas, 152.3 x 232 cm. (Dulwich Picture Gallery, London)

Provenance and attribution

Little is known about the early history of ownership of Samson and Delilah: either who owned it or where it was displayed. Yet, the position of the figures—peering down—might suggest that it was hung high. Moreover, the presence of a ledge at the bottom of a painting could have an architectural significance, indicating perhaps that the work was hung over a mantel. By the early 18th century the painting was recorded in Amsterdam, and was later bought by Noel Desenfans (the founder of Dulwich Picture Gallery) at a London sale in 1783. The painting formed part of the core collection of Dulwich Picture Gallery, when it opened in 1811. Yet, until 1880, it was considered to be the work of Peter Paul Rubens. Today, the painting’s attribution is restored to Van Dyck and stands as an important example of the artist’s early work and the influence of Rubens on his career.

Special thanks to the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

This essay was produced in conjunction with the [“Making Discoveries”](http://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/2016/january/making-discoveries-lineup/ ) display series at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. The displays coincide with the release of the Gallery’s Dutch and Flemish Schools Catalogue, to be published fall 2016, and aims to disseminate important findings from this major research project.