Esztergom Basilica, Esztergom, Hungary, 19th century (photo: © Google Street View)

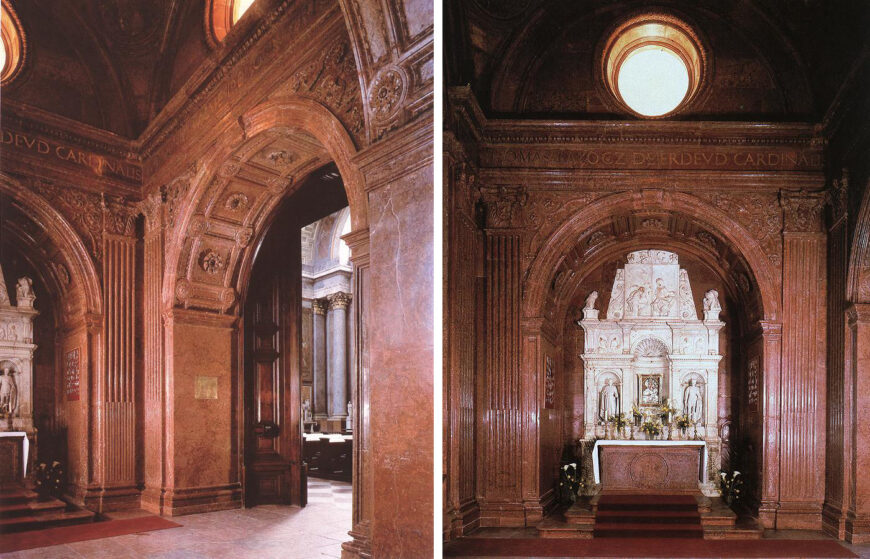

When you enter the monumental 19th-century Basilica in Esztergom in Hungary (today about an hour north of Budapest), you may notice a small, much older chapel that sits just left of the nave. Visitors are drawn to the chapel by the sight of the shiny red marble covering the chapel walls, which is further accentuated by the contrast with a white marble altarpiece occupying the back wall. This is Bakócz Chapel, the only element deemed worthy of saving from the old cathedral, built more than 300 years earlier.

Jacopo di Biagio di Camicia, Bakócz Chapel in Esztergom Basilica, Esztergom, Hungary, 1506–07, red marble (photo: Fine Arts in Hungary)

A surviving Renaissance chapel

The foundation stone of the chapel was laid in 1506, and by the next year, most of the structure was finished. The façade and the bronze dome of the chapel were finished during the following years, while the main altar of the chapel was installed in 1519. Sources tell us that Tamás Bakócz, the Archbishop of Esztergom from 1497–1521 had richly equipped the chapel (which served as his place of burial) with liturgical objects, gold and silver utensils, and expensive vestments. He also left other treasures in the chapel, but they were later confiscated by King Louis II. The chapel, as well as a few surviving objects—such as a monumental gradual commissioned by him and a chasuble—testify to his patronage in Esztergom.

Left: Bakócz Gradual, early 16th century, Ms. I. 1a, folio 1 recto (Bibliotheca Ecclesiae Metropolitanae Strigoniensis, Esztergom); right: Chasuble, 1500–1510 (Esztergom Cathedral)

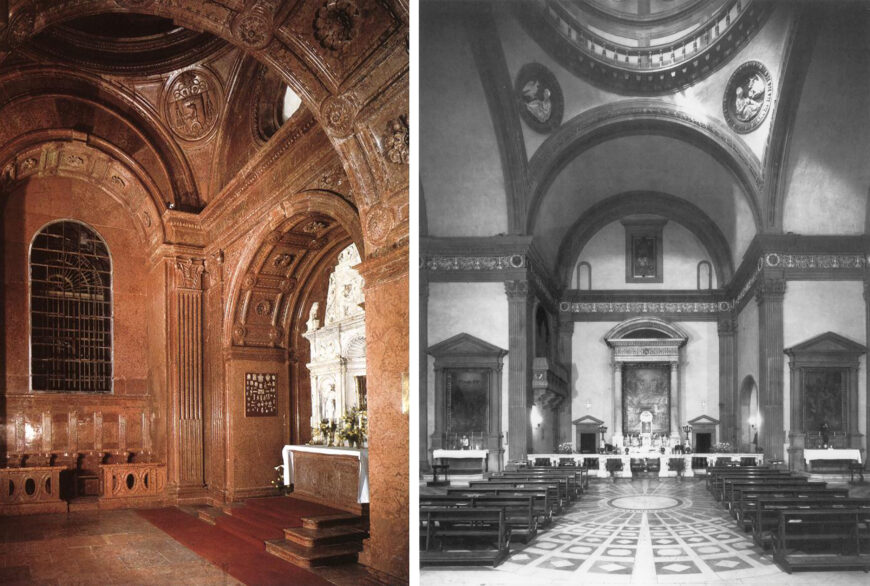

The Bakócz chapel is the earliest Italian Renaissance-style building north of the Alps. It is also the first fully Renaissance-era, centrally planned ecclesiastical building outside of Italy. It is a groundbreaking and influential structure, which uniquely fuses the style of Tuscan (central Italian) early Renaissance with Hungarian architectural traditions.

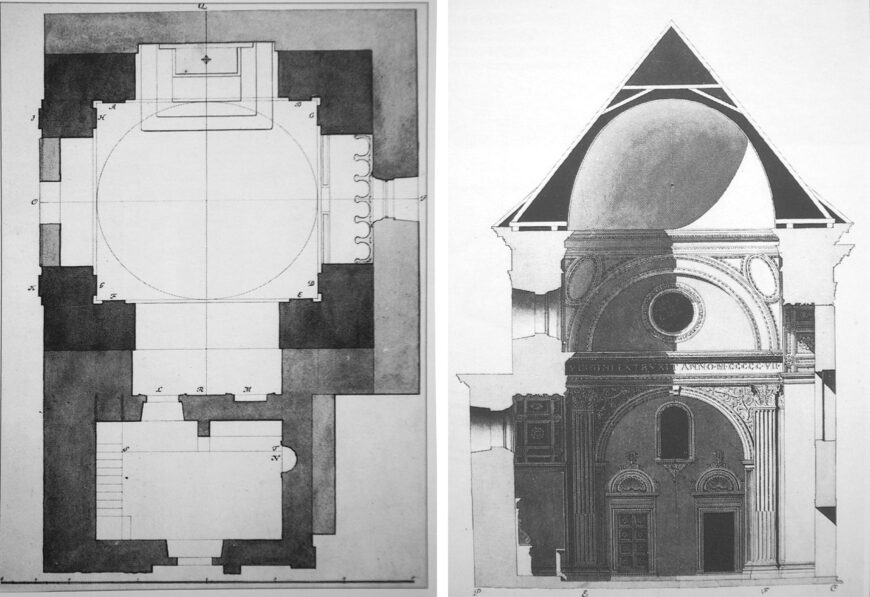

In 1823, the chapel was dismantled and was later rebuilt block-by-block, incorporated into the fabric of the Neoclassical building. The orientation of the chapel was turned around and the building lost its original façade. The original configuration of the chapel is known from numerous drawings. The plan is based on a Greek cross. This architectural shape of the structure is part of a long sequence of centrally-planned Italian chapels, including Brunelleschi’s Old Sacristy in San Lorenzo and the Sacristy of Santo Spirito, both in Florence. The Santo Spirito Sacristy and the small chapel of the Barbadori family attached to it, both designed by architect Giuliano da Sangallo between 1488–97, are the closest analogy to the Bakócz chapel. Giuliano da Sangallo’s Santa Maria delle Carceri church in Prato (1485–91) is a more monumental and free-standing version of such a centrally-planned space.

Left: Jacopo di Biagio di Camicia, Bakócz Chapel in Esztergom Basilica, Esztergom, Hungary, 1506–07, red marble (photo: Fine Arts in Hungary); right: Giuliano da Sangallo, Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato, Italy

The Florentine structures, however, generally used grey stone (pietra serena) for elements of the architectural articulation, combined with plain white walls. In contrast, the chapel in Esztergom was built entirely from red marble. This building material—in reality a local red limestone, quarried in the hills near Esztergom—has been used in Hungary since the late 12th century. It was clearly the patron’s request to conform to this tradition, while at the same time red marble, with its ancient and imperial associations, seemed perfectly fitting as a medium for his funerary chapel.

The cornice of the chapel, running around the inside of the building above the wall niches, contains a large inscription in antiqua letters, referring to the founder and the year of completion:

THOMAS BAKOCZ DE ERDEUD CARDINALIS — STRIGONIENSIS ALME DEI GENITRICI MARIE — VIRGINI EXTRUXIT ANNO M CCCCC VII

Thomas Bakócz of Erdőd, Cardinal of Esztergom, built this to the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary, in the year 1507

Originally, the letters were inserted in bronze. In fact, the original dome of the chapel was also made of bronze and decorated with a total of 96 reliefs (these did not survive the rebuilding of the chapel). The four pendentives are decorated with a coat of arms.

Andrea Ferrucci, Altar, 1519, white marble (Bakócz Chapel in Esztergom Basilica, Esztergom, Hungary; photo: Fine Arts in Hungary)

The masters of the chapel

Some documents recently published by Doris Carl shine light on the masters of the Bakócz chapel. The architect of the chapel can be identified as Jacopo di Biagio di Camicia, who arrived in Hungary first around 1477. In Florence, he had worked on a wooden model for the inner façade of the basilica of Santo Spirito and was a close collaborator of Giovanni di Mariano and Salvi d’Andrea, who worked on the realization of Brunelleschi’s plan. The Florentine sculptor Andrea Ferrucci—identified by Giorgio Vasari as the master of the chapel—executed the white marble altar of the chapel. This was delivered to Esztergom in 1519. Of the original carvings, only the kneeling figure of the patron next to the central niche as well as the scene of the Annunciation on the top remain. A similar white marble altarpiece of Ferrucci, originally from Fiesole, is now at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The leading master of the stone carvers executing the ornamental decoration of the Bakócz Chapel is probably Domenico Baccelli, who was Giuliano da Sangallo’s nephew and who was trained in the workshop of Jacopo del Mazza and Andrea Ferrucci. He was also master of the Pécs tabernacle, and it was most likely his workshop that executed two similar red marble tabernacles in the parish church of Our Lady in Pest (present-day Budapest). The identification of these masters shines new light not only on the extensive presence of Florentine artists in late-15th-century Hungary but also on the connections of Bakócz’s architectural project with earlier works carried out for King Matthias Corvinus in Buda.

The Florentine sculptor Ioannes Fiorentinus (Giovanni Fiorentino) worked on the execution of the chapel. He was a prolific stone carver, based in Esztergom, who usually worked in red marble, and often signed his works. These were exported to far-away towns, such as Gniezno in Poland, Zagreb, and even to Transylvania. He can be identified as one of the carvers of the decoration of the Bakócz-chapel, along with at least two other unidentified sculptors.