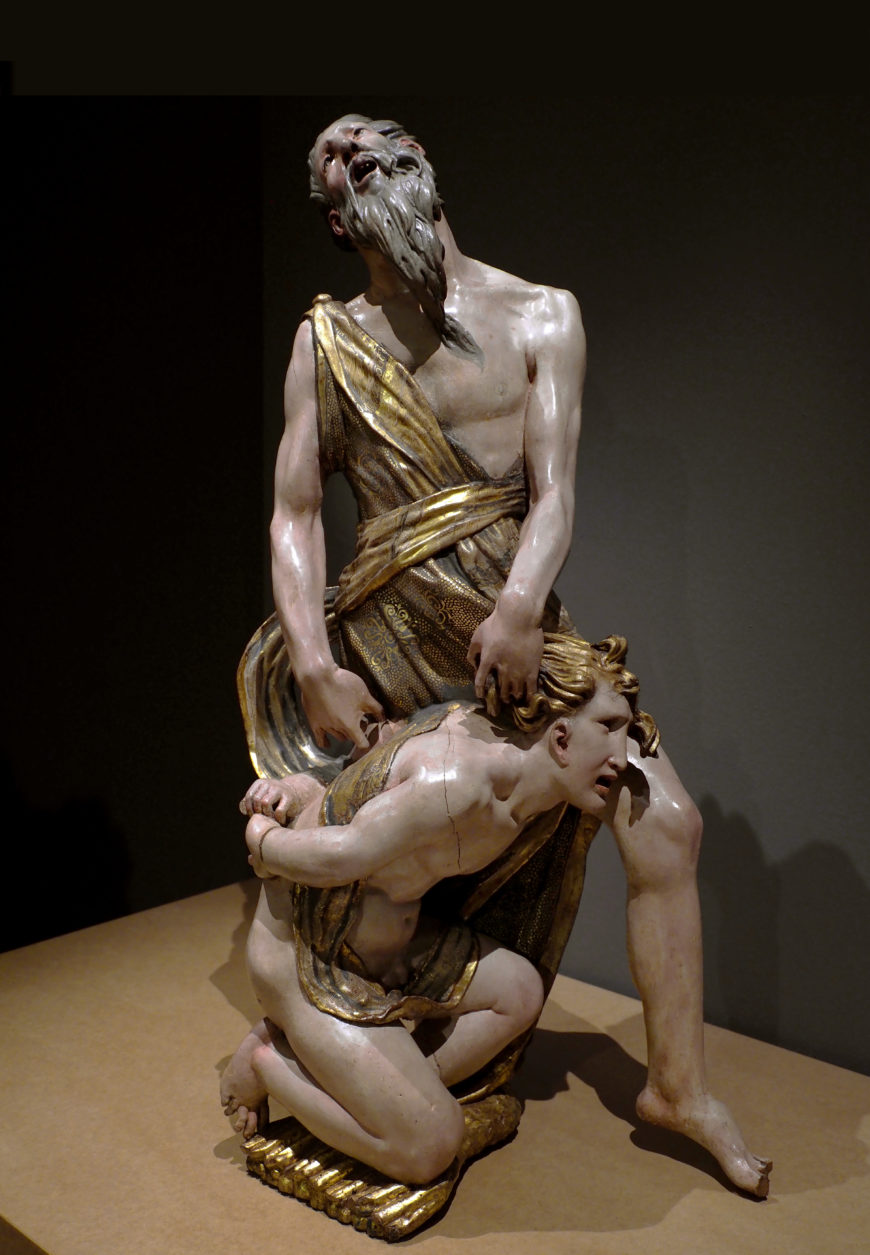

Alonso Berruguete, Abraham and Isaac, 1526–1532, polychromed wood, 89 x 46 x 32 cm (Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid; photo: Iglesia en Valladolid, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Alonso Berruguete is possibly the most famous sculptor that you have never heard of. He began his life in Paredes de Nava, a small town in northern Castile, which was by no means a major artistic center. From these remote beginnings, Berruguete rose to extraordinary success, courting some of the wealthiest and most powerful patrons on the Iberian Peninsula (what is today Spain and Portugal). After his death, Berruguete was eulogized by his peers as among the greatest artists of his time, and sculptures like his Abraham and Isaac were among the works of art for which he was most enthusiastically celebrated. Indeed, Abraham and Isaac was part of the larger-scale sculptural work that cemented Berruguete’s reputation as one of the most exciting sculptors in renaissance Spain.

Reconstruction of the Retablo Mayor of San Benito el Real, 1526–32, Valladolid. The outlined works on this reconstruction of the altarpiece of San Benito were on view in the exhibition Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance from October 13, 2019 to February 17, 2020 at the National Gallery of Art. Areas in gray have been lost. (Photo: Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid)

The Retablo of San Benito el Real

Abraham and Isaac is one small piece of a commission that Berruguete received in 1526 from the Monastery of San Benito el Real in Valladolid, the cultural capital of the region of Castile and León. The commission was for a retablo (a large and elaborate wooden altarpiece) of the kind that was installed in churches all over Spain. Berruguete was at a crucial turning point in his career, having already finished his artistic training and gone to work, however briefly, for King Charles I of Spain (later Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor). By then, Berruguete commanded an impressive workshop of assistants and was ready to take on his most ambitious project yet.

San Benito (in the central niche) on the Retablo Mayor de Benito, 1526–32, Valladolid, Spain (photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY 4.0)

Like other retablos of the period, the Retablo of San Benito el Real is a visually dazzling combination of sculpted, painted, and architectural elements (although it was at one point split apart and no longer exists in its finished state). Scenes from the Christian Bible—some fully painted, others carved in relief and then polychromed—appear framed by richly ornamented columns and pedestals. The life-sized figure of Saint Benedict (San Benito in Spanish) towers at the center of the composition, his hand lifted in blessing. At the top of the retablo is an enormous gilded shell with the Crucifixion rising above it. At the bottom is a series of architectural niches (many of which do not survive), each of which contained biblical figures sculpted in the round. Abraham and Isaac originally stood in one of these niches.

The subject and iconography

The subject of Abraham and Isaac derives from a story in the Old Testament. In the Book of Genesis, God tells Abraham, a shepherd and the first of the patriarchs of Judaism, to offer his only son, Isaac, as a sacrifice to Him. Following God’s instructions, Abraham takes Isaac to a mountaintop, where he prepares an altar with firewood. He binds his son and lays him on the altar, lifting a knife to kill him. Before Abraham can do so however, an angel appears from Heaven and stops him, replacing Isaac with a lamb for the sacrifice. In Abraham’s willingness to take His commands over and against his love for his only child, God sees an expression of Abraham’s faith and rewards that faith with the promise of more sons to come.

Titian, The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1542–44, oil on canvas, 328 x 285 cm (Santa Maria della Salute, Venice)

Depictions of this scene in renaissance art are overwhelmingly focused on the dramatic actions that drive this story forward: Abraham’s swinging of the knife into the air, or God’s angel tumbling down from the sky in a moment of literal divine intervention. This is the approach taken by contemporaries like Titian, Paolo Veronese, and Andrea del Sarto.

Alonso Berruguete, detail of Abraham in Abraham and Isaac, 1526–1532, polychromed wood, 89 x 46 x 32 cm (Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid; photo: Iglesia en Valladolid, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Berruguete’s approach suggests a different set of priorities, heightening instead the intensity of emotions expressed by Abraham and Isaac. The sculpture represents a moment of despair, the faces of both father and son distorted into screams. They do not yet know that salvation is coming. They only know the deed that is to be done—and the tremendous cost of it.

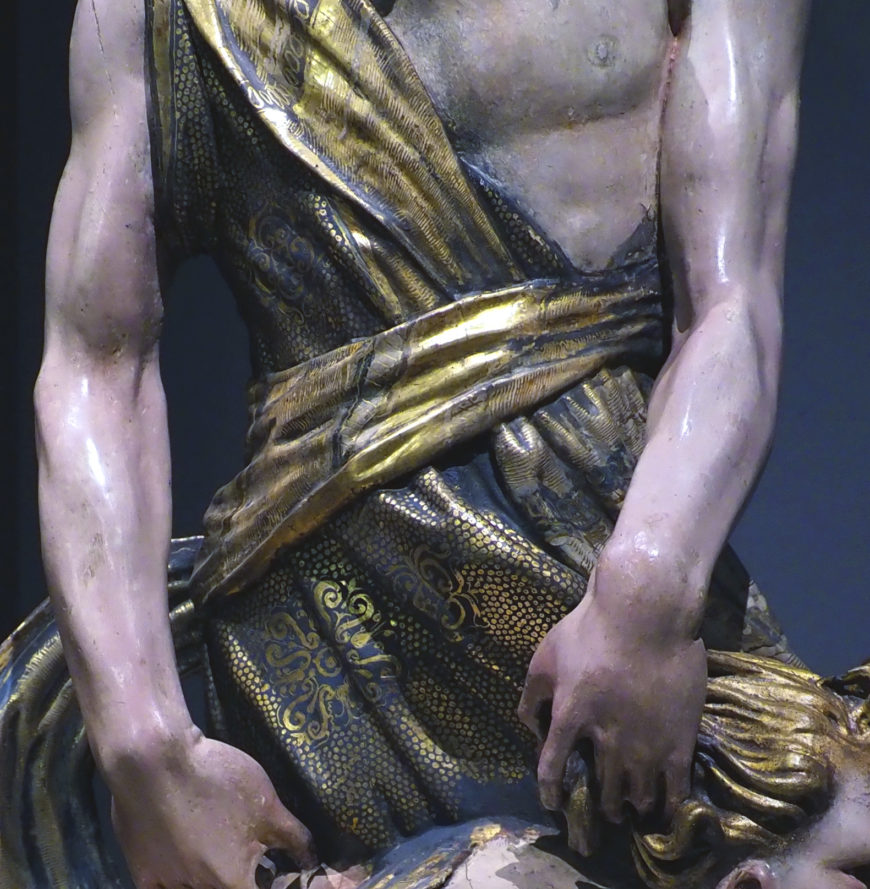

Alonso Berruguete, detail of Abraham’s clothes showing the estofado technique, Abraham and Isaac, 1526–1532, polychromed wood, 89 x 46 x 32 cm (Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid; photo: Iglesia en Valladolid, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Techniques in polychrome

The affective power of Berruguete’s wooden sculpture is thanks in part to its brilliant polychrome. The draperies that wrap around the body of Abraham and swirl across Isaac’s torso were made using the Spanish estofado technique. Berruguete and his assistants would have begun by covering the finished wooden figures first in gesso (glue mixed with plaster), then in bole (largely made of clay). After dampening the surface with water, gold-leaf was carefully applied, let dry, and polished. Finally, a layer of tempera was painted over the gilding. Once dry, the paint was scratched away to reveal the gold layer underneath, resulting in glittering geometric and floral designs.

But the sculpture gets its lifelikeness especially from the technique used to paint the faces and bodies of Abraham and Isaac, called encarnación. These parts of the sculpture, once covered in gesso, were then coated in lead white paint. From there, the details of skin tone and hair were carefully painted in, with pink glazes used to give the sculpture the warmth and vitality of human life. Each stage of the production of a polychrome sculpture—from carving to estofado and encarnación—would have required a particular skill set. Berruguete’s workshop employed carpenters, gilders, painters, woodcarvers, and other specialists who worked together under his guidance to realize his grand designs.

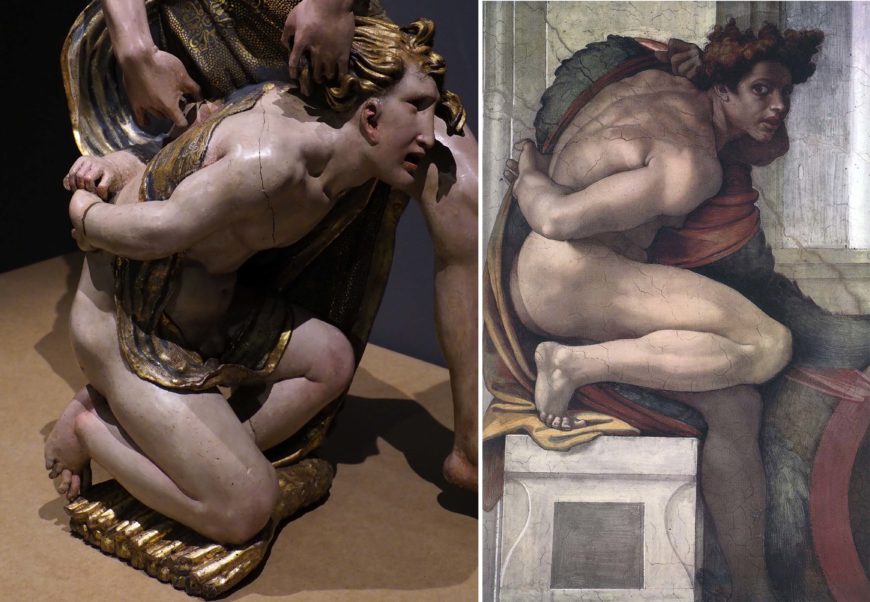

Left: Alonso Berruguete, Abraham and Isaac, 1526–1532, polychromed wood, 89 x 46 x 32 cm (Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid; photo: Iglesia en Valladolid, CC BY-SA 2.0); right: Michelangelo, Ignudo, c. 1511, fresco, part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (Vatican Museums)

Michelangelo’s Laocoön

Abraham and Isaac also owes much to Berruguete’s training in Italy. Sometime between around 1506 and 1518, Berruguete travelled between Florence, Rome, and other major centers to study art. While there, he came into the orbit of Michelangelo, who at the time was occupied with the painting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. It was a transformative phase for Berruguete. In these years, he made several drawings and paintings that reflect his careful study of Michelangelo’s work. This study paid off when Berruguete returned to Spain and got to work on sculptural commissions like the Retablo of San Benito el Real. Several of the figures on the retablo owe their poses to the sibyls and prophets on Michelangelo’s ceiling, including those depicted in Abraham and Isaac. With his torso bent over and his arms twisted behind his back, Berruguete’s Isaac is a close copy of one of the many nudes in Michelangelo’s famous fresco.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Berruguete’s travels in Italy also coincided with an important moment in the history of renaissance art. In 1506, an ancient marble was excavated in Rome: Laocoön, a Hellenistic work depicting a scene from Virgil’s Aeneid. In this scene, a Trojan priest and his two sons are consumed by giant snakes that emerged from the sea. As a striking portrayal of human agony, the sculpture was a sensation. None other than Michelangelo was tasked with its restoration.

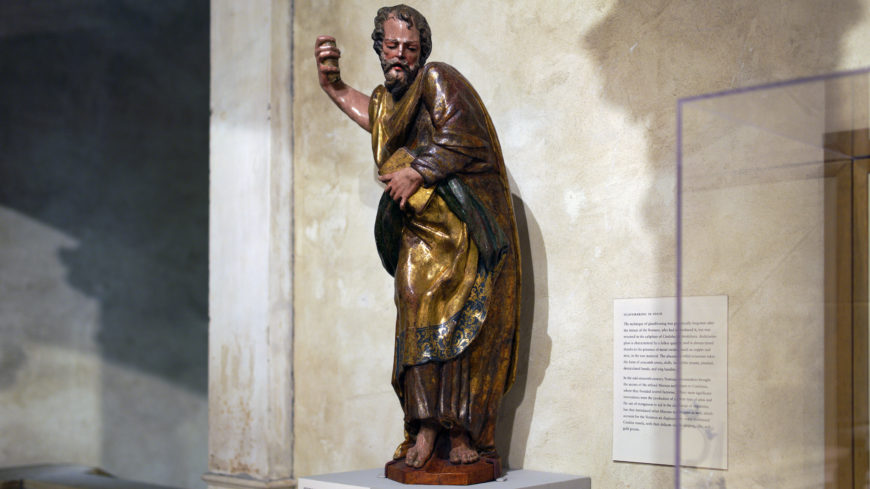

Alonso Berruguete, Apostle or Saint, c. 1520s, polychrome and gilded walnut, 103 x 37 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There can be no doubt that Berruguete saw this sculpture and appreciated what it could teach him about the expressive power of art. In its basic composition, Berruguete’s Abraham and Isaac perhaps more closely resembles a sculpture like Donatello’s take on the same subject, made for the Florentine Duomo in 1421, but its extreme pathos was drawn from Laöcoon, a work whose influence can be felt all over the twisting bodies and contorted faces that came to characterize Berruguete’s sculpted output, such as the saint or apostle now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Berruguete’s Tomb of Cardinal Juan Pardo de Tavera and El Greco’s Laocoön

Alonso Berruguete, Tomb of Cardinal Juan de Tavera, 1554-61 (for the Hospital de San Juan Bautista, Toledo, photo: Factum Foundation, and view the 3d reconstruction)

Berruguete’s ability to convey intense emotion in his sculptures remained one of the hallmarks of his oeuvre through the end of his life. His last great work was a marble tomb of the Cardinal Juan Pardo de Tavera, the archbishop of Toledo, for the Hospital de San Juan Bautista. Even here Berruguete demonstrates his ability to capture the depth of human feeling. The tomb depicts the cardinal at the moment of his death. His eyelids fall heavily over his eyes, and his cheeks appear sunken and hollow. Nestled against this fading face is another one—a shrieking figure on the crozier tucked against the cardinal’s cheek. Here, we see the echoes of Abraham and Isaac’s screaming visages.

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (El Greco), Laocoön, c. 1610/14, oil on canvas, 137.5 x 172.5 cm (The National Gallery of Art)

Tavera’s marble tomb remains in Toledo, where Berruguete spent the final decades of his life and career. He cannot have known that less than twenty years later Toledo would nurture another luminary of Spanish art: Doménikos Theotokópoulos (an artist who was originally from Crete), now best known as “El Greco.” Berruguete’s brilliance was not lost on the rising painter. In marginal notes that he made in his copy of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, El Greco praised Berruguete’s accomplishments in painting, sculpture, and architecture. Almost exactly a century after Berruguete saw Laocoön in Italy, El Greco made a painting of the very same subject. It is hard to imagine that he did so without the legacy of the Spanish renaissance master in mind.

Notes:

- D. Dickerson III and Mark McDonald, eds., Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain (Washington: National Gallery of Art; Dallas: Meadows Museum, SMU; Madrid and New York: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica/Center for Spain in America; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019)

Additional resources

Watch a short video about Berruguete from the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain

Read “Berruguete in Process: The Retablo of San Benito” from the National Gallery of Art

Learn more about how to make a Spanish polychrome sculpture from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Watch a short video in ASL about El Greco’s Laocoön from the National Gallery of Art

Manuel Arias Martínez, ed., Son of the Laocoön. Alonso Berruguete and Pagan Antiquity (Madrid: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2018)

Lynn Catterson, “Michelangelo’s ‘Laocoön?’,” Artibus et Historiae 26, no. 52 (2005), pp. 29–56

Sepulchre of Cardenal Tavera by Factum Foundation