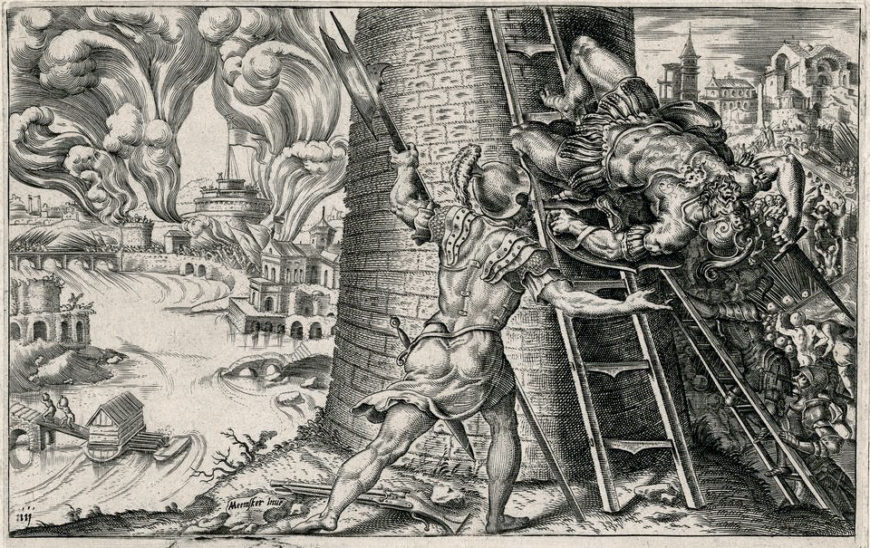

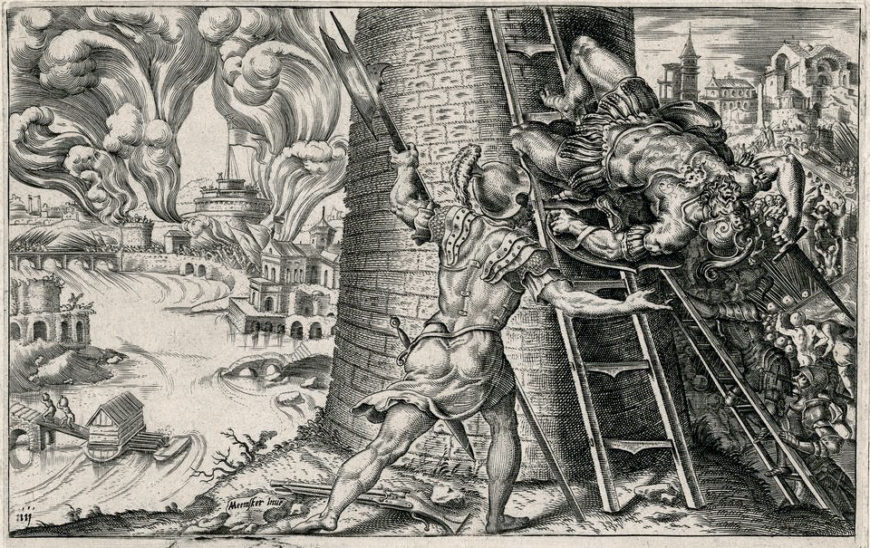

Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert, after Martin van Heemskerck, Sack of Rome in 1527 (and the Death of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon), engraving and etching on paper, in Divi Caroli (The Victories of Emperor Charles V), 1555/6, published by Hieronymus Cock (© Trustees of the British Museum). Charles III falls to his death as his Spanish and German (largely Lutheran) troops attack the Borgo (a neighborhood in Rome). Pope Clement VI is imprisoned in the Castel Sant’Angelo, which is on fire in the background. Heemskerck’s image was made almost 30 years after the sack, when Charles V abdicated and was soon to die.

When night fell and the enemy entered Rome, we in the Castello, and most particularly myself, who has always delighted in seeing new things, stood there contemplating this unbelievable spectacle and conflagration, which was of a magnitude that those who were situated in any other spot but the Castello would neither see or imagine. Benvenuto Cellini, in his autobiography, My Life (composed between 1558 and 1566) [1]

Forces under the banner of Charles V sack Rome

On May 6, 1527, the unthinkable occurred. An army of more than 20,000 soldiers invaded Rome—the Eternal City—and violently looted and pillaged it for over a month. During this time, German and Spanish soldiers under the banner of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, the Holy Roman Empire plundered churches and palaces, held cardinals and merchants for ransom, and killed men and women from all walks of life in the streets and in their homes. Rome had not suffered such a humiliating and catastrophic defeat by a foreign army since the sack of the city in 410 C.E. at the hands of the Visigoths.

For contemporaries, the sack was an “unbelievable spectacle and conflagration”—to use the words of the Florentine goldsmith and artist, Benvenuto Cellini—that left Rome ruined and its population dispersed. For an entire year, civic and cultural life in the city stopped in its tracks. It would take years for Rome to recover.

It’s important to keep in mind that at that time, Italy was not unified as a nation-state. Rather it was a collection of city-states dominated by the Papal States (the lands of the papacy), the Republic of Venice, the Republic of Florence, the Duchy of Milan, and the Kingdom of Naples.

Modern scholars see the Sack of Rome as an important turning point in the history of Rome and the papacy. Many have interpreted the event as ending the golden age of the High Renaissance, embodied by the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, and hastening the onset of the Counter Reformation and its emphasis on piety and morality.

Regardless, the Sack of 1527 was a traumatic event that displaced artisans, artists, and humanists of the papal court and city; and imprinted a painful memory on the generation that experienced it.

Part of the Italian Wars

The Sack of Rome occurred amid the Italian Wars which saw French, Spanish and Imperial armies (the armies of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V) fight for dominance over the cities and states of the Italian peninsula. Once independent city-states and kingdoms, most of the Italian powers, such as the Republic of Florence, the Duchy of Milan, and the Kingdom of Naples, had come under the control and influence of Charles V.

Resentful of Charles’s power in the peninsula, Pope Clement VII organized the League of Cognac in 1526 with France, Venice, Milan, and Florence to counter-balance the influence of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in Italy. This alliance between the papacy, France, and many Italian city-states opened a new phase of the Italian Wars called the War of the League of Cognac (1526–30).

Charles V’s forces, numbering more than 20,000 Spaniards, Italians, and Germans quickly asserted itself in northern Italy, delivering several losses to the forces of the League of Cognac near Milan. However, the army was poorly equipped and even lacked the heavy artillery necessary to besiege walled cities.

The landsknechts were German mercenaries who fought in the Imperial armies during the first half of the sixteenth century. They were famed for their ferocity and skill with pikes. The landsknechts were known for their outlandish attire, which inspired fear on the battlefield. Daniel Hopfer, Landsknechte, c. 1530, etching, 20.2 × 37.7 cm (The Art Institute of Chicago)

To make matters worse, the soldiers had not been paid for months and had taken to living off the land to survive. Consequently, they mutinied and forced their general, Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, to march on Rome. Many of the Germans soldiers—mercenaries soldiers called landsknechts—were Protestants who eagerly looked forward to attacking papal Rome as a religious calling and to pillaging the famed wealth of the popes.

The assault

In the early morning of May 6, 1527, Charles III, Duke of Bourbon and his forces began their assault on Rome. Despite Rome’s massive walls (built in the third century C.E. by the Roman emperor Aurelian), the Imperial army found the city ill-prepared for the attack. Besides a contingent of Swiss guards, the city’s defenders could only muster 5,000 militiamen, composed of artisans, artists (like Cellini), and priests. In a bold move, the Duke of Bourbon personally led his men as they scaled the walls of Rome at the district of Trastevere. Wearing his characteristic white cloak, Bourbon was shot dead early in the attack by Cellini—if we are to believe his recounting of the sack.

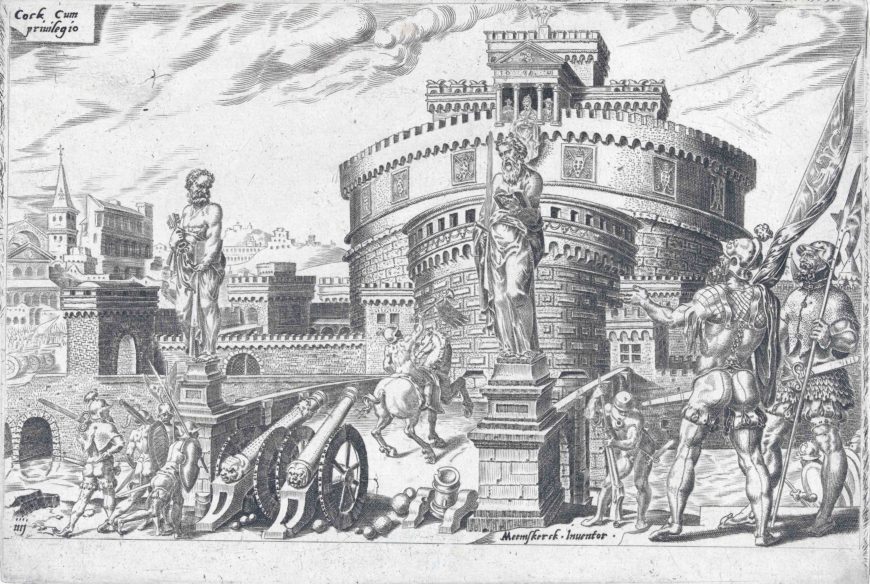

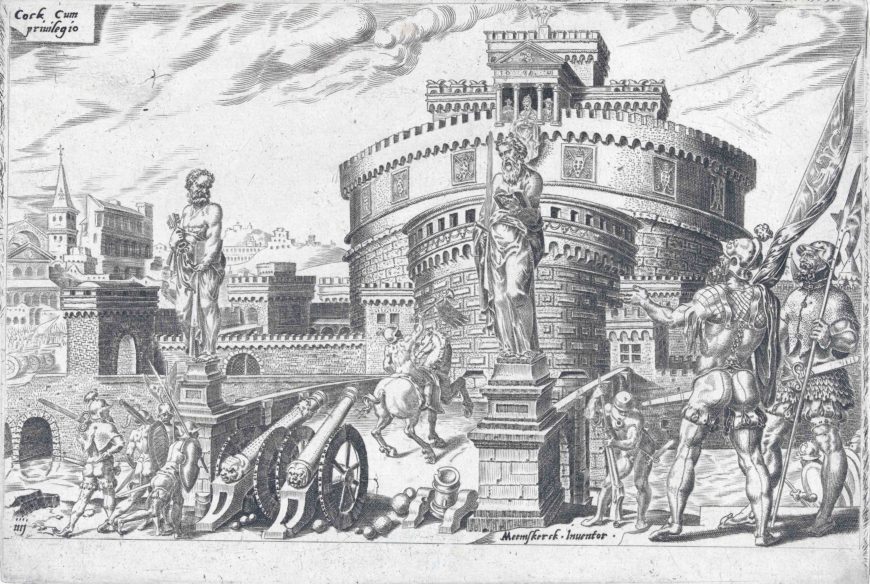

In this engraving of the sack, the siege of Castel Sant’Angelo is portrayed. The pope and two other prelates look upon the action from a balcony. Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert, after Martin van Heemskerck, Lansknechte in Front of Castel’Angelo in 1527, copper engraving in (The Victories of Emperor Charles V), 1555/6, published by Hieronymus Cock, 15.6 × 23.2 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Despite the loss of their general, the imperial forces breached the wall and swarmed into Rome, finding to their disbelief that none of the bridges connecting Trastevere to Rome had been destroyed. Quickly, the motley collection of Spaniards and Germans marched over Ponte Sisto, through the Banchi, and across Ponte Sant’Angelo to the Vatican, “killing everyone in their path.” [2]

Cardinals, prelates, and citizens all stumbled over one another in their mad rush to flee the massacre. Much of the court hid inside Castel Sant’Angelo (the ancient mausoleum of the Roman emperor, Hadrian, which had been converted into a fortress and a prison in the fourteenth century), the tall fortress on the Tiber that protected the entrance to the district around the Vatican.

Pope Clement VII, who had been praying in his private chapel, had to be rushed by cardinals and servants to the fortress through a secret pathway. Witnesses later recounted the pope’s narrow escape. According to one account, if he “had tarried for three more creeds, he would have been taken prisoner in his own palace.” [3] For an entire month, the imperial forced besieged the fortress as more than a thousand courtiers and prelates survived on dwindling supplies. Finally, on June 6, Clement VII surrendered agreeing to pay a ransom of 400,000 ducats for his freedom.

The ruin of the Eternal City

“Hell was a more beautiful sight to behold.” Marin Sanuto [4]

So wrote the Venetian chronicler, Marin Sanuto, in describing the destruction wrought by the imperial army on the city and people of Rome. Numerous other diaries, letters, and contemporary histories attest to the violence and looting that took place during the sack. According to these accounts, the soldiers pillaged churches and palaces, tortured merchants to discover where they kept their fortunes, ransomed cardinals and prelates for thousands of ducats, and murdered men and women indiscriminately.

The engraving shows a German soldier dressed as the pope being paraded through the streets of Rome. In the background, fighting and pillaging ensues. In the distance, Castel Sant’Angelo and Ponte Sant’Angelo can be seen. Mattäus Merian, “Sack of Rome,” engraving in Johann Ludwig Gottfried’s Historiche Chronica (Frankfurt 1630–34), p. 33.

Much of this violence took on an anti-clerical and anti-Catholic tone with the Lutheran landsknechts stripping churches of all their valuables and mocking the relics found in their treasuries. Contemporaries described how the relics of Saints Peter and Paul were trampled underfoot, the Sudarium of Christ was sold in taverns, and a priest was killed for not administering the sacraments to a mule dressed in ecclesiastical vestments. One group even elected Martin Luther as pope and carried one of their own in his stead, dressed as the pope in ritual derision of the pope and the papacy—a moment visualized in a seventeenth-century engraving by Mattäus Merian.

The aftermath of the Sack

Clement VII and his court, despite surrendering, were held prisoners in Castel Sant’Angelo until he paid the 400,000-ducat ransom. The pope paid a few of these installments before escaping on December 7, 1527 to Orvieto, a nearby city on the border between the Papal States and Tuscany. Here, Clement held court until October 7, 1528, when it was deemed safe to return to Rome. He came back to a ruined city. The population of Rome, which before the sack numbered about 55,000 in habitants, had been reduced to a quarter of its previous size. Much of this population loss can be attributed to merchants, artists, and other temporary visitors fleeing the city. Although exact numbers are hard to come by, scholars estimate that at least ten percent of Rome’s population died in the sack and occupation of the city by the Imperial forces. It would take thirty years for Rome to reach its pre-Sack population.

Giorgio Vasari, Pope Clement VII in Conversation with Charles V, c. 1560. This painting by the Florentine painter and art critic, Giorgio Vasari, depicts the pope and emperor in conversation as equals. Note that Clement VII was beardless before the sack. He grew the beard as a form of mourning on account of the sack and his time spent in “exile” at Orvieto. The papal court soon followed his example and started to grow beards, helping to further popularize an already growing fashion for keeping beards in the sixteenth century.

Soon after the sack, Pope Clement VII and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, publicly reconciled when the emperor met the pope in Bologna, where the emperor was crowned by the pope in 1530. Although the traditional coronation ceremony long emphasized papal authority over the Empire, this time the ritual belied Charles V’s domination of Italian affairs. In the months of negotiation leading up to the coronation, Clement VII had to accept the emperor’s influence in secular and ecclesiastical affairs, most notably Charles’s leading position in the Italian peninsula and his call for a council to reform the church—what would later evolve into the Council of Trent. For the next two centuries, popes had to navigate between their own aspirations to power and the demands of secular leaders such as Charles V.

The impact of the Sack of Rome on art

The Sack of Rome also had a long-lasting impact on the cultural and artistic life of papal Rome. The sack displaced many artists and humanists working at the papal court. The art historian André Chastel has called this displacement of artists a “diaspora.” [5] A diaspora is a forced dispersal of a large group of people, often entire populations, from their homeland. The term originally applied to the forced displacement of Jews, especially after the Jewish-Roman Wars (66–73 C.E.). The term has since been applied to any large-scale displacement of people.

Long an artistic center that attracted the likes of Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo, Rome was not the same after the sack. Many artists, finding it hard to secure patronage in Rome, moved to courts in France and the Holy Roman Empire. The painter, Rosso Fiorentino, who suffered at the hands of German soldiers during the sack, found employment at the royal court of King of France in order to escape “a certain kind of wretchedness and poverty.” [6] In transferring to these courts, artists helped disseminate the burgeoning Mannerist style beyond Rome and Florence.

It has been suggested that the events of 1527 brought an abrupt end to the High Renaissance—although arguments like this might be a little too strong since Clement’s successor, the popular Roman pope, Paul III, initiated a restoration of Rome’s glory through a program of reform, city-planning, and art patronage.

The Sack of Rome in art

A new spirit infused art commissioned by the popes and prelates of the church after the sack. This art was inspired by the reform movements within the church and emphasized piety and doctrine, erasing any of the “pagan” elements of the High Renaissance (most famously embodied by the painter Giulio Romano’s erotic images, I Modi). These trends were already in motion prior to the sack, but some scholars emphasize the role of the events of 1527 in hastening this change. Popes after Clement VII tended to commission works of art that glorified the Church, proclaimed papal supremacy, and educated the faithful in proper doctrine.

Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert, after Martin van Heemskerck, Sack of Rome in 1527 (and the Death of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon), engraving and etching on paper, in Divi Caroli (The Victories of Emperor Charles V), 1555/6, published by Hieronymus Cock (© Trustees of the British Museum).

In the years after 1527, humanists and chroniclers wrote about the Sack of Rome and its consequences. However, Italian artists did not produce any works that grappled with the sack itself in its immediate aftermath—perhaps the memory of the event was too painful for the generation that witnessed it to process it through art. One of first portrayals of the sack appeared in 1556 with a series of twelve engravings, The Victories of Charles V, based on the drawings of the Dutch painter, Martin van Heemskerck. The engravings, printed in the Netherlands, celebrated the emperor’s reign after his abdication of the Spanish throne in favor of his son, Philip II.

Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert, after Martin van Heemskerck, Lansknechte in Front of Castel’Angelo in 1527, copper engraving in (The Victories of Emperor Charles V), 1555/6, published by Hieronymus Cock, 15.6 × 23.2 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Although Charles V was personally embarrassed by the Sack of Rome, the publisher who commissioned the engravings, Hieronymus Cock, thought it worthy enough to include among the images of the emperor’s victories in the Italian Wars and in his battles against Protestants in Germany. The engravings proved popular and were printed seven times between 1556 and 1640, prolonging the memory of the Italian Wars and the Sack of Rome, and serving as inspiration for artistic depictions of these events.

Workshop of Guido Durantino, also known as Guido Fontana, maiolica plate, An Episode from the Sack of Rome, 1527: The Assault on the Borgo (the district where the Vatican was located), c. 1540. The plate depicts the Duke of Bourbon leading the imperial forces to the walls of Rome. Castel Sant’Angelo and Ponte Sant’Angelo can be seen in the background.

Meanwhile, one of the first Italian depictions of the sack oddly occurred in the most mundane of all places—a colorful maiolica plate produced by the workshop of Guido Durantino around 1540 in Urbino. The details of the plate’s commission are unknown, but its patron surely wanted the memory of sack to live on while entertaining dinner guests.

Notes:

[1] Benvenuto Cellini, My Life, trans. Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 62.

[2] Luigi Guicciardini, The Sack of Rome, trans. James H. McGregor (Italic Press, 1993), p. 96.

[3] Judith Hook, The Sack of Rome, 1527 (Palgrave, 2004), p. 165.

[4] Judith Hook, The Sack of Rome, 1527 (Palgrave, 2004), p. 167.

[5] André Chastel, The Sack of Rome, 1527, trans. Beth Archer, Princeton University Press, 1983, p. 3.

[6] Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, trans. Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (Oxford, 1991), p. 353

Additional resources:

André Chastel, The Sack of Rome, 1527 (Princeton University, 1983)

Jessica Goethals, “Vanquished Bodies, Weaponized Words: Pietro Aretino’s Conflicting Portraits of the Sexes and the Sack of Rome,” I Tatti: Studies in the Italian Renaissance 17 (2014): pp. 55–78

Kenneth Gouwens, Remembering the Renaissance: Humanist Narratives of the Sack of Rome (Brill, 1998)

Luigi Guicciardini, The Sack of Rome (Italica Press, 1993)

Judith Hook, The Sack of Rome, 1527 (Palgrave, 2004)

Bart Rosier, “The Victories of Charles V: A Series of Prints by Marteen van Heemskerck, 1555-1556,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 20 (1990–1991), pp. 24–38

Idan Sherer, “A Bloody Carnival? Charles V’s Soldiers and the Sack of Rome,” Renaissance Studies 34 (2020): pp. 784–802