Three Bini-Portuguese spoons, in the collection of Cosimo I de’ Medici Duke of Florence by 1560, ivory, Benin, 25, 24.8 and 25.7 cm long (Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Firenze, sezione di Archeologia e Etnologia; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Eating is a universal activity, but in Renaissance Europe using a spoon made from the ivory of an elephant’s tooth (known as the tusk) was a statement of status. African elephants are the largest land mammals, and beautiful spoons crafted in West Africa and then imported into Portugal in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, were a novelty. Transforming an elephant tusk into an object, whether functional or decorative, required the dense ivory to be cut, carved, and polished, and necessitated considerable artistry.

When Portuguese traders first arrived in West Africa in the later fifteenth century, they found local carvers making exquisite ivory goods, and the traders recognized their potential as luxury objects to be sold in Europe. Spoons are the oldest utensils for serving and eating food, and feature in most cultures around the world. Ivory spoons made in Africa became part of the fabric of elite life in places like Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, during the period of the Renaissance when Europe was coming increasingly in direct contact with West African communities.

The Portuguese imperial project turned Lisbon into a global city, full of different objects from all corners of the globe. Ivory spoons made in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century West Africa would have been a natural choice for Portuguese of a certain social status interested in purchasing something from outside Europe that was simultaneously reassuringly familiar and also alluringly unfamiliar. Such spoons could be used for serving and eating food by a member of the elite social class, but could also be put on display as works of art in a noble or royal Renaissance collection.

Two types of spoons

The two types of extant ivory spoons originating in Africa in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are Sapi-Portuguese from Sierra Leone and Bini-Portuguese from Benin. They can be distinguished by their form and decoration, with differing handles, bowls, proportions and hooks.

Sapi-Portuguese spoons

The first African ivory spoons to appear in Lisbon were Sapi-Portuguese. They were given this label as Sapi was the name used by Portuguese traders for the coastal peoples of Sierra Leone. Ships carrying the spoons had set off from São Jorge da Mina on the Gold Coast. In addition, some also called at Sierra Leone, where the Bullom people were recorded as making “ivory spoons of better design and workmanship than in any other part.” Unfortunately, the survival rate of Sapi-Portuguese spoons has not been high—only about 10 are known today.

Spoon (Sapi-Portuguese), 1490–1530, ivory, Sierra Leone, 24 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Sapi-Portuguese spoons often have intricate non-figurative decoration on their handles supplemented on occasion by crocodiles and snakes. They also have shallower, smaller bowls than their Bini-Portuguese counterparts. A very fine example of a Sapi-Portuguese spoon at the highest end of the artistic range is now in the British Museum in London.

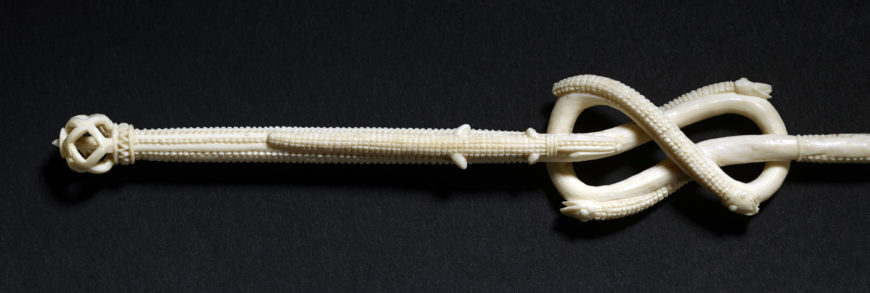

Detail of the handle. Spoon (Sapi-Portuguese), 1490–1530, ivory, Sierra Leone, 24 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Carved from a single piece of ivory, its handle expertly combines the linear effect produced by an almost perfectly straight crocodile with the curves of an intricate figure-of-eight knot around which are wrapped three snakes. Although the handle is very elaborately decorated, other underlying characteristics of Sapi-Portuguese spoons still pertain, so the bowl is shallow, thin, fig-shaped, and one third the length of the whole, and the overall effect is of great elegance. The spoon is a hybrid, with its material and parts of its decoration recognizably African (for example, the reptiles) and other parts of its decoration, such as the figure-of-eight and openwork boss, recognizably European.

Bini-Portuguese spoon (left) with a detail of the bird on the top (right), Benin, sixteenth century, ivory, 25.4 cm (private collection, Lisbon; left photo: Mário Roque, right photo: Kate Lowe)

Bini-Portuguese spoons

Over 50 surviving ivory spoons of very distinctive and elegant form make up the category usually labeled as Bini-Portuguese on account of their traditional ascription to production in Benin. The handles of Bini-Portuguese spoons almost always feature an African bird, animal, fish or shell. The bowls of Bini-Portuguese spoons are larger in relation to the spoon as a whole, and their hooks are much more pronounced than their Sapi-Portuguese counterparts.

They appear not to have arrived in Lisbon until the mid-sixteenth century. The earliest European description of ivory spoons from the coastal area around the mouth of the River Benin dates to 1588, when James Welsh, the captain of a trading vessel, mentioned “spoones of Elephants teeth very curiously wrought with divers proportions of foules and beasts upon them.” [1]

One such spoon in a private collection features a long-legged bird with a decurved beak in an unusual action, perhaps preening the feathers of an outstretched wing, connected via another part of the handle to the head of a straight-horned antelope. The bowl under the trademark hook is thin, translucent and not entirely symmetrical.

A Medici inventory in Florence of 1560 included 5 of these spoons, but described them incorrectly as “mother-of-pearl” rather than ivory, presumably because both materials were translucent but mother-of-pearl was more familiar to the inventory taker. The ivory spoons were transported by ship from West Africa to Portugal, but then were sometimes sent to other parts of Europe as gifts to princes and rulers (which probably explains their appearance in the Medici collection in Florence).

A silver spoon made in Lisbon has a visible silver mark (detail on the right), dating it to the reign of King Manuel I. Spoon, silver, 16th century, Lisbon (private collection, photos: Mário Roque)

Silver spoons

Homegrown spoons were made in silver by Portuguese and other European silversmiths. The foremost scholar of fifteenth and sixteenth-century African ivories, Ezio Bassani, believed that Portuguese metal spoons served as “models to African carvers” for the Sapi-Portuguese spoons brought to Lisbon during the Renaissance, which would explain the similarity of their shapes and aspects of the decoration of their handles. A unique early sixteenth-century Portuguese silver spoon now in a private collection has a visible silver mark, dating it to the reign of King Manuel I (1495–1521). The handles of ivory spoons made in Sierra Leone quite closely resemble the handle of the Portuguese silver spoon made in Lisbon. The silver handle is separated into three sections; one section is quadrangular, the other two sections are rounded, and the sections are separated by pearled rings. The bowl is fig-shaped. This spoon is an important piece of evidence in the debate over the degree of influence that European metal spoons exercised on the design and decoration of Sapi- and Bini-Portuguese ivory spoons.

Ivory spoons in documents

The earliest references to ivory spoons in Lisbon appear in lists of possessions from 1497 and 1498 of two men with links to the royal court, suggesting that a royal connection might have facilitated access to non-European goods. In addition, receipts of payments of customs duties imposed on 114 ivory spoons and 22 wooden spoons imported into Lisbon are listed in the one surviving account book of the treasurer of the Guinea House, for the financial year 1504–05. These spoons were brought to Lisbon by sailors of varied income levels, and many of the spoons may have been quite utilitarian. The spoon from the 1498 inventory was valued at 180 reais, and five silver spoons in the same inventory were together valued at 850 reais (that is, each spoon was worth 170 reais). So in this instance the ivory and silver spoons were considered to be worth approximately the same amount, giving equivalence to the two types of material. As a point of comparison, in 1501 a skilled worker in Lisbon could have earned 55 reais a day, and an unskilled laborer 35 reais a day [2]. The ivory spoons on which customs duties were paid in 1504–05 were valued at between 40 and 100 reais, which is considerably less than the valuation given to the ivory spoon from 1498.

Follower or workshop of Frei Carlos, Virgin and Child with Angel, early 16th century, oil on panel, 102 x 98 cm (Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga; photo: © Paulo Alexandrino)

Sapi-Portuguese spoons in Renaissance Portuguese paintings

Early sixteenth-century Portuguese paintings offer another way to visualize these spoons, in terms of how they were used as well as the status they implied of their owner. At least five sixteenth-century panel paintings include what appear to be representations of ivory Sapi-Portuguese spoons, or silver spoons similar to those upon which West African spoons may have been modeled. None depicts a Bini-Portuguese spoon. Very importantly, the representations of the spoons indicate how these global objects were used once in Lisbon. Originally in the monastery of São Vicente de Fora, a painting from the workshop of Frei Carlos of the Virgin and Child with an angel, dated c. 1530, shows an ivory Sapi-Portuguese spoon in a lipped plate held by the angel, containing food for the Christ Child. This painting elucidates two points: first that the ivory spoons could be used functionally for eating, conveying food into mouths rather than just serving food, in addition to being kept as display objects, and that they were also markers of social importance.

Detail of plate with spoon. Follower or workshop of Frei Carlos, Virgin and Child with Angel, early 16th century, oil on panel, 102 x 98 cm (Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga; photo: © Paulo Alexandrino)

The similarity of the placement of the spoons in the five paintings is striking: they all lie in bowls or lipped plates, on low tables next to or at the foot of beds, in religiously charged scenes of great moment. Their connectivity to food is unmistakable—but not to “ordinary” food. African spoons were being used as implements to nourish the most important people in the Christian world: the Virgin, the Christ Child, saints, and cardinals. The spoons, while at one level merely a fashionable accessory, at another were clearly significant in their signaling of the status of certain global objects, specifically suited to their purpose of being employed by critical figures in the Catholic Church. Although they were details that were peripheral to the main focus of the paintings, and of relatively small size, in terms of their spatial positioning within the compositions the spoons are also surprisingly prominent; in most cases, they are either in the immediate foreground, or in the center of the whole composition. The fact that these spoons were used in imagined biblical scenes and episodes from saints’ lives by Portuguese artists in the second and third decades of the sixteenth century suggests that this was a common detail often inserted into paintings at the time, and that more such representations may once have existed.

Three Bini-Portuguese spoons, in the collection of Cosimo I de’ Medici Duke of Florence by 1560, ivory, Benin, 25, 24.8 and 25.7 cm long (Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Firenze, sezione di Archeologia e Etnologia; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There are large gaps in our knowledge about African spoons in Renaissance Lisbon. But, against all the odds, examples of both Sapi- and Bini-Portuguese spoons have either survived materially, or left traces in the documentary or visual record, allowing their presence and their contemporary worth to be reassessed 500 years later.

Notes:

[1] James Welsh, “A voyage to Benin beyond the country of Guinea made by Master James Welsh, who set forth in the yeere 1588,” in The Second Part of this Second Volume containing the Principall Navigations Voyages Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, ed. Richard Hakluyt (London: George Bishop, Ralph Newberie, and Robert Barker, 1599), p. 129.

[2] Information from the Prices, Wages and Rents in Portugal, 1300–1910 project.

Additional resources

Ezio Bassani and William B. Fagg, Africa and the Renaissance: Art in Ivory (New York: The Center for African Art, 1988).

Ezio Bassani, African Art and Artefacts in European Collections, 1400–1800, ed. Malcolm McLeod (London: The British Museum Press, 2000).

Kate Lowe, “Made in Africa: West African luxury goods for Lisbon’s markets,” in Annemarie Jordan Gschwend and K. J. P. Lowe ed., The Global City: On the Streets of Renaissance Lisbon (London: Paul Holberton publishing, 2015), pp. 162–77.