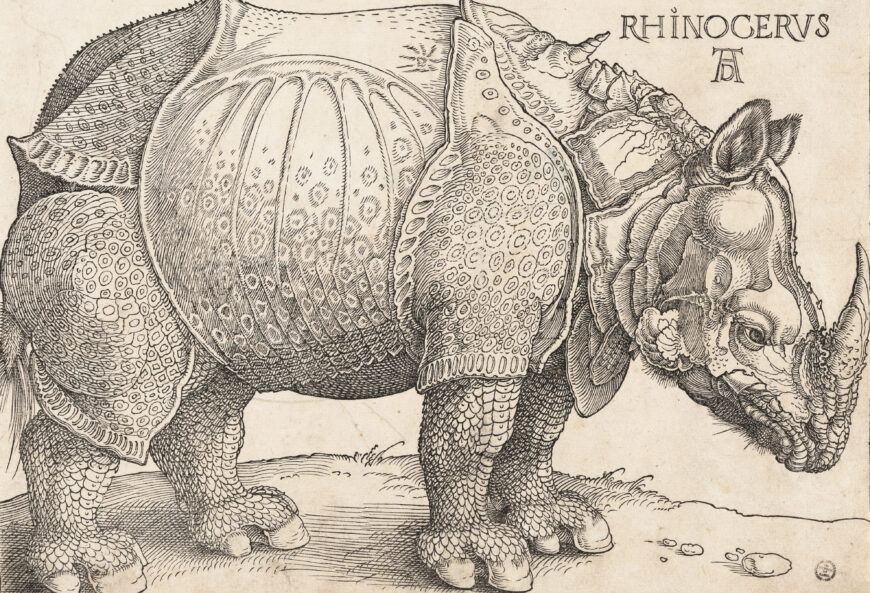

Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks, measuring almost twelve feet tall and ten feet wide (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Emperor Maximilian I as sovereign of the Order of the Golden Fleece, c. 1500, from the Livre des ordonnances de la Toison d’or (Austrian National Library)

Most prints of the early modern era (c. 1400–1800) consist of a single sheet, about letter size. But during the early sixteenth century, artists across Europe discovered that by joining sheets together, they could form a much larger composite image. [1]

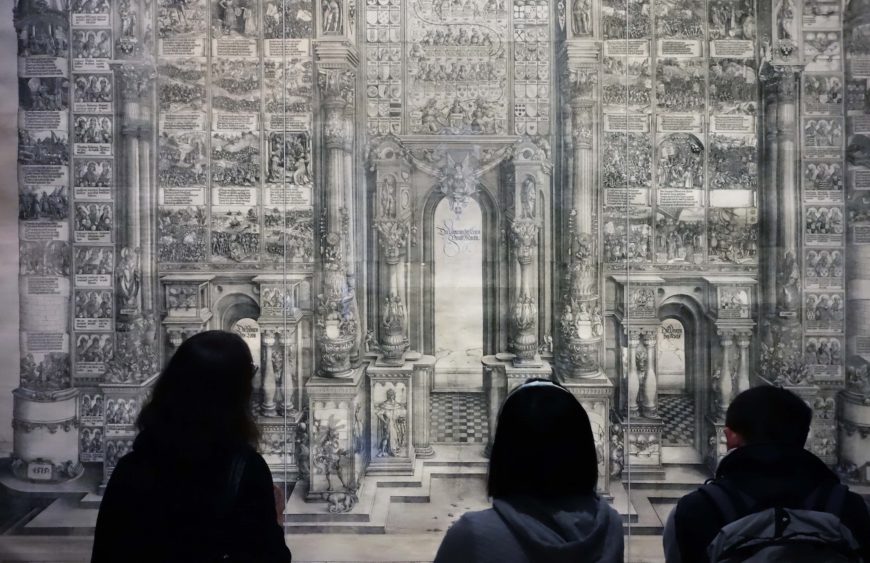

The one we are discussing in this essay is by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and other artists in his workshop. It measures almost twelve feet high! Comprised out of almost 200 separate smaller sheets, assembled into an overall image of a fantastic arch with three openings, this massive woodcut serves to glorify the Emperor, his family tree, his accomplishments (especially in battles), and his princely interests.

Most of those early large-scale works were woodcuts, printed from carved blocks, allowing them to be combined with texts composed from movable type.

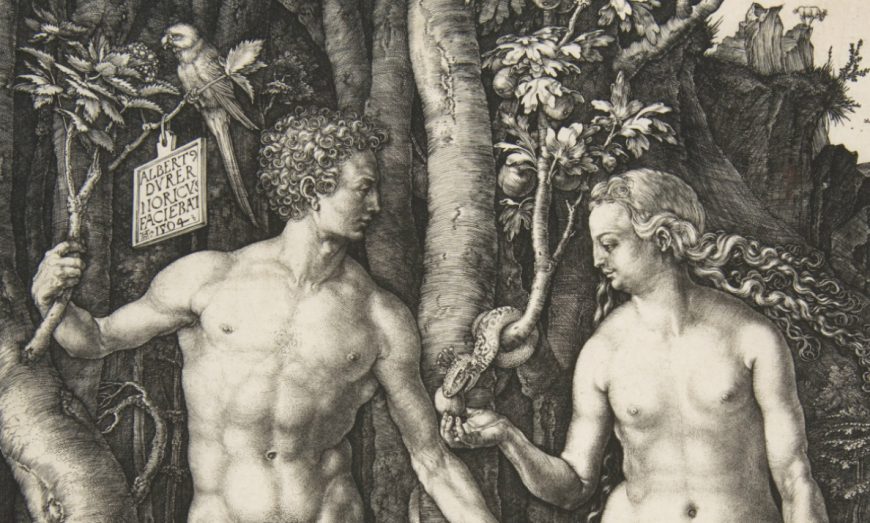

Prints for personal glory

Within the far-flung territories of the Holy Roman Empire, such prints offered a ruler new opportunities for outreach and image formation through the use of these most recent circulating media. No other ruler was so quick to recognize the opportunity to employ prints for personal glory than Emperor Maximilian I of the Habsburg dynasty (who ruled the Holy Roman Empire from 1493–1519). He coordinated the efforts of authors and illustrators to produce a series of volumes about his glorious ancestry, his political talents and deeds, and his noble, chivalrous values. [2]

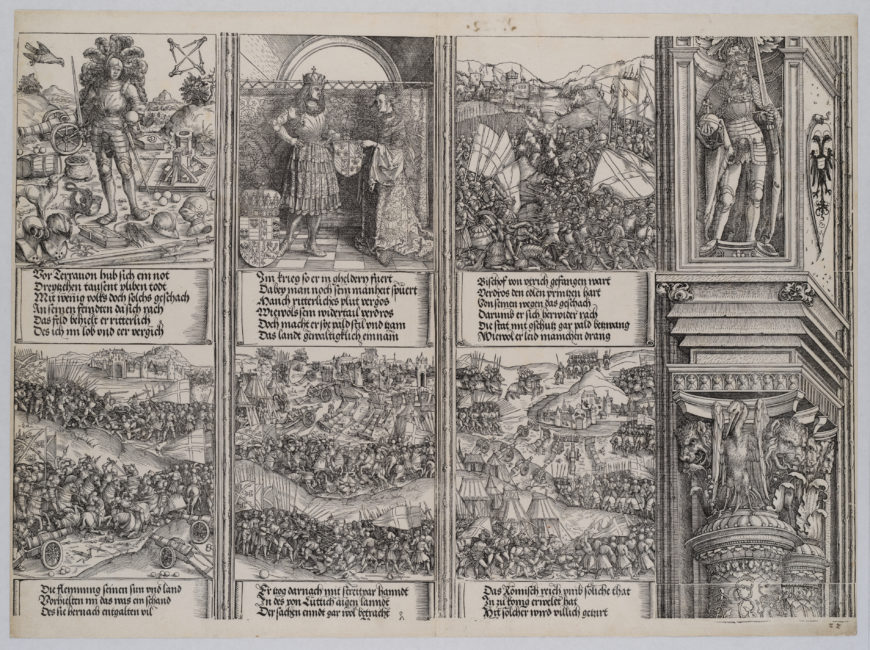

Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

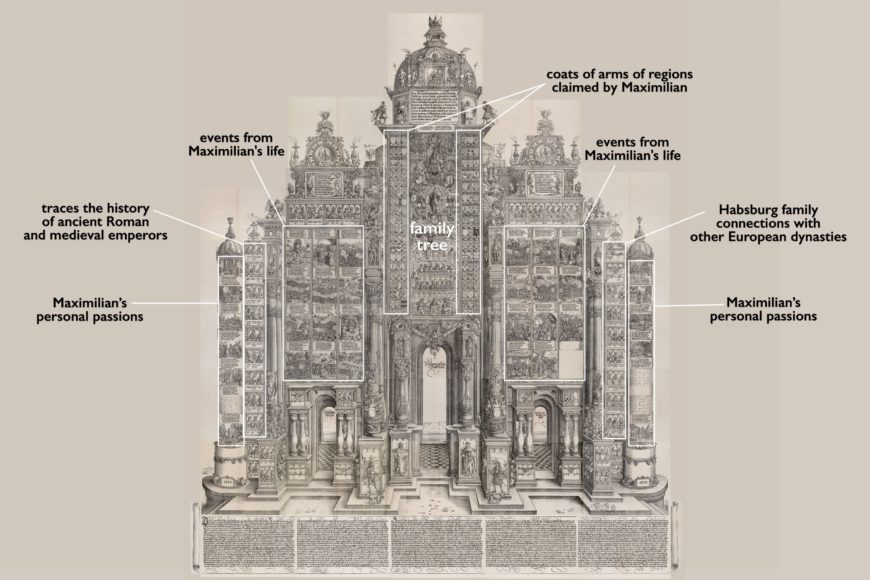

Maximilian’s most ambitious woodcut project assembled almost 200 individual woodcuts to construct a massive arch, called the Arch of Honor. While based on the idea of ancient Roman triumphal arches (which were erected in celebration of a glorious military victory), Maximilian’s Arch remained a mere paper tribute, with its own distinctive complex of imagery. In effect, the ensemble is much more complicated and filled with imagery than the basic open, flat-topped arches of ancient Rome. Instead, it is crowded with narratives, allegories, and named individuals, including former emperors, relatives among European rulers, and a central family tree.

The effect on a viewer of encountering this massive structure can be intimidating due to its sheer size. Yet the wealth of pictorial details on so many individual woodcuts also threaten to overwhelm the eye, though rhyming quatrain captions beneath the historical images help one decipher the sections and navigate the overall structure.

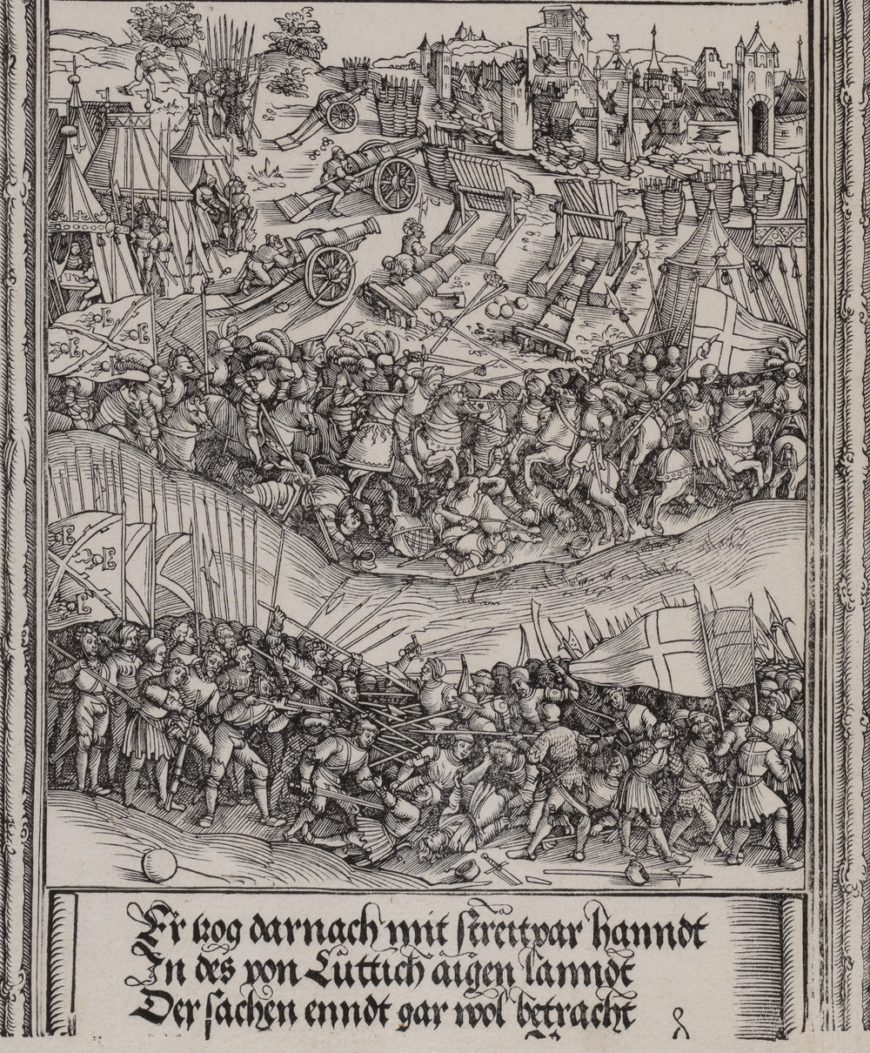

Infantry, cavalry and portable artillery, detail, Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Some of the major narrative Arch woodcuts celebrated the emperor’s military deeds (encompassing many of his campaigns, especially against the rival armies of the French king). These images also display the presence of a new coordinated professional military, which features large-scale infantry, complemented by traditional cavalry, but now supplemented with a newer military weapon resource, portable artillery.

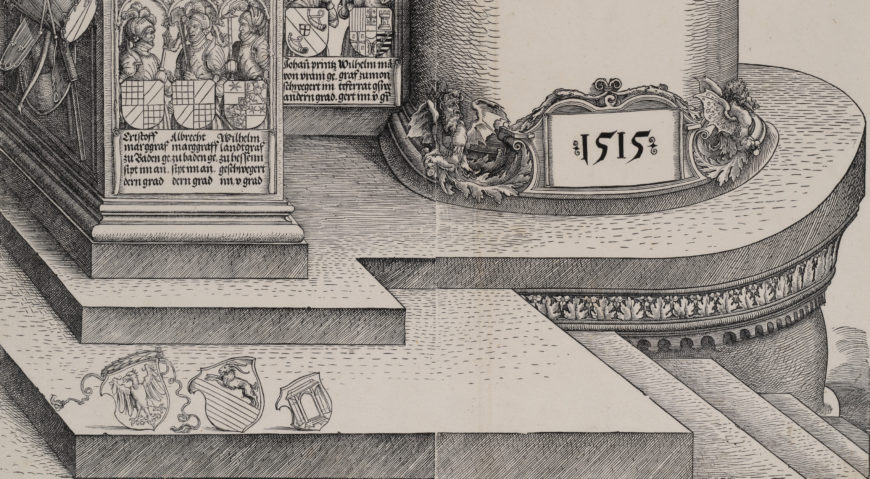

Coats of arms framing the family tree (detail), Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

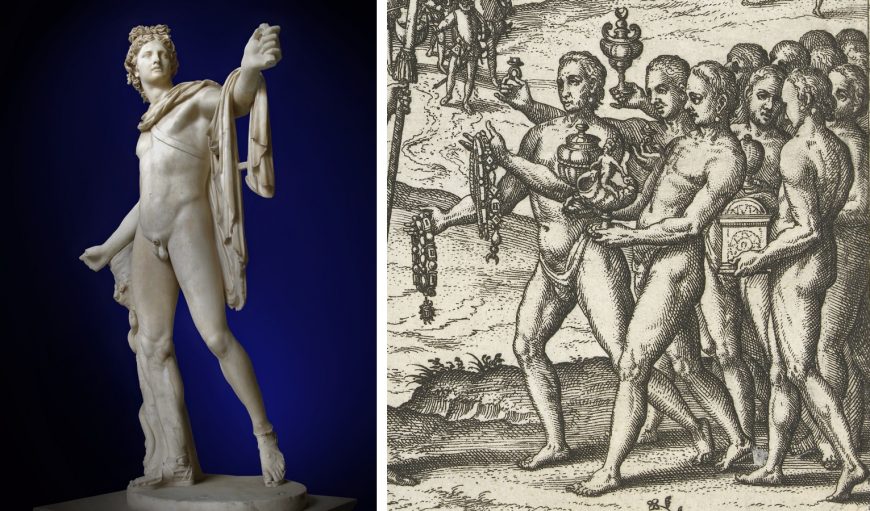

Other images in the historical section included his ambitious dynastic activity: Maximilian used strategic marriages to other royal houses to expand his territories—as noted, extending to Spain (through his children) and greater Hungary (his grandchildren), creating the foundation of the later Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The tall central tower makes its own territorial claims by showing the coats of arms of the many regions claimed by Maximilian (including fantasy claims to Jerusalem and regions of Italy, the former ruled by the Ottomans, the latter contested with France and local rulers). These flank an image of a family tree whose roots go all the way back to ancient Troy and pre-Christian Europe—raising claims by the dynasty to go back to ancient epic heroes besides Roman emperors—before rising to include later generations starting with the first Christian king of the Franks, Clovis, falsely claimed (along with the great King Charlemagne later) as an illustrious Habsburg ancestor by Maximilian. Eventually the genealogy culminates in the larger figures of Maximilian’s own imperial parents as well as his offspring successors, including two eventual Holy Roman Emperors.

Habsburg family connections extended through kinship to numerous other European dynasties, and those relations appear as portraits with labels at the right side. The corresponding left side traces the history of Roman emperors well into medieval rulers with that title, also labeled. Thus Maximilian doubly underscores his authority—through noble blood ties on one side and imperial authority on the other.

A final pair of towers at the edges unspools Maximilian’s personal passions, areas where he made landmark contributions: jousting tournaments with armor, heraldry, and knightly brotherhoods; but also hunts, artillery, and constructions, both buildings and an elaborate tomb for his imperial father.

Taken together, then, the Arch of Honor provides elaborate praise of Maximilian I as the ideal emperor, a paragon of modern rulership, guided by traditional chivalric values but also aggressively modern in both diplomacy and warfare. [3]

Detail. Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

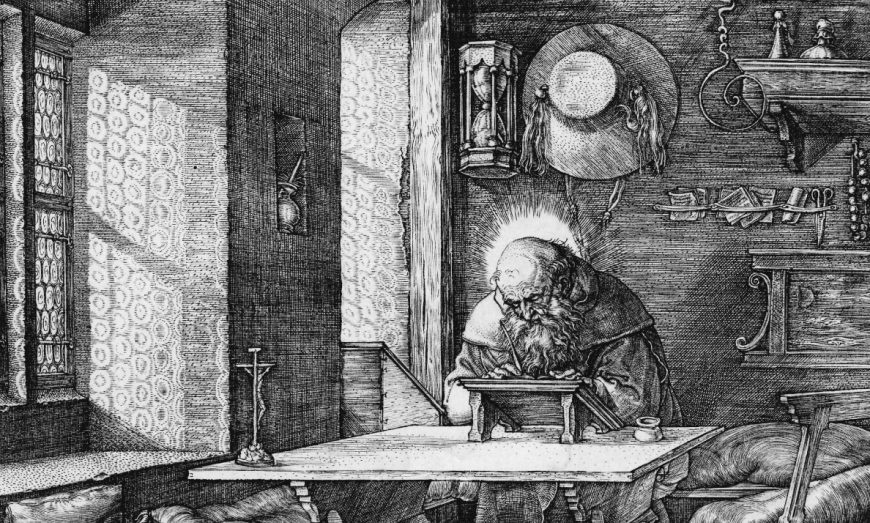

Who made the Arch?

The Arch of Honor involved collaboration between authors of the accompanying texts as well as teams of artists to design the woodcuts for professional cutters to carve on wood blocks for printing. Principal artistic responsibility was given to Germany’s most celebrated contemporary printmaker and painter from Nuremberg, Albrecht Dürer. Only a few of the scores of woodcuts stem directly from Dürer’s own hand, so he clearly delegated other portions to a variety of artists from his workshop; their names are known but their precise division of labor remains undocumented. The outer towers were executed by a second artist, Albrecht Altdorfer of Regensburg. Delegating such a large project to designers of the Dürer workshop as well as Altdorfer was necessitated by the scale of the project as well as the speed required by an aging Maximilian, who died shortly after the work was completed.

Marriage of Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy (detail), Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Close attention to individual sheets reveals the care taken by both designers and cutters to realize intricate details of battlefields or scenes of marriage with accompanying coats of arms. In detail, the intricacy of linear networks for shading as well as for representation provide convincing depictions of figures and settings, despite the limitations of black and white and of carved wooden lines.

Coats of arms of Stabius, Kölderer, and Dürer (detail), Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, 1515, printed 1517–18, woodcut, 36 sheets of large folio paper printed from 195 woodblocks (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

An overview is also provided on a colophon text (the five columns of text at the bottom of the print) by court historian Johannes Stabius. Tiny coats of arms of the collaborators, including Stabius and Dürer, appear on a step at the lower right corner of the Arch.

Printing and distribution

Production of the Arch of Honor was essentially completed by 1515 but was delayed in release while Maximilian ordered his court historians to add further research into his purported early ancestry. Only a small number of proofs were completed before the emperor’s death, so most of the early printings of complete sets of the Arch were only made and distributed by his grandson Ferdinand I in 1526. Another edition appeared from the Habsburgs in 1559. With a later revival of Habsburg ruling house interest in their heritage, restrikes from the original blocks (still housed in Vienna, in the Albertina Museum) were made at the end of the 18th century. However, the impermanence of its paper support means that few of the original copies of the Arch survive. A very few show added coloration. But most sets currently in museums derive from later restrikes.

Emperor Maximilian I has been called “the last knight” by earlier historians because of his commitment to such pastimes as jousting and exclusive chivalric brotherhoods. But in his military tactics and innovations, in his dynastic ambitions, and, finally, in his use of the latest contemporary media to create his image and legacy—particularly through a work like the Arch of Honor—he stands on the cusp of modern politics.