Japanese Haiku. Black and white movies. Zen ink drawings. Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites. What do all these have to do with a 16th-century carved wooden altarpiece? They all share an aesthetic of restraint, of less is more, of evocative intimation rather than bold declaration.

Priest celebrating the Eucharist (detail), Rogier van der Weyden, The Seven Sacraments, 1440–45, oil on panel, 200 x 223 cm (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp)

A more understated altarpiece

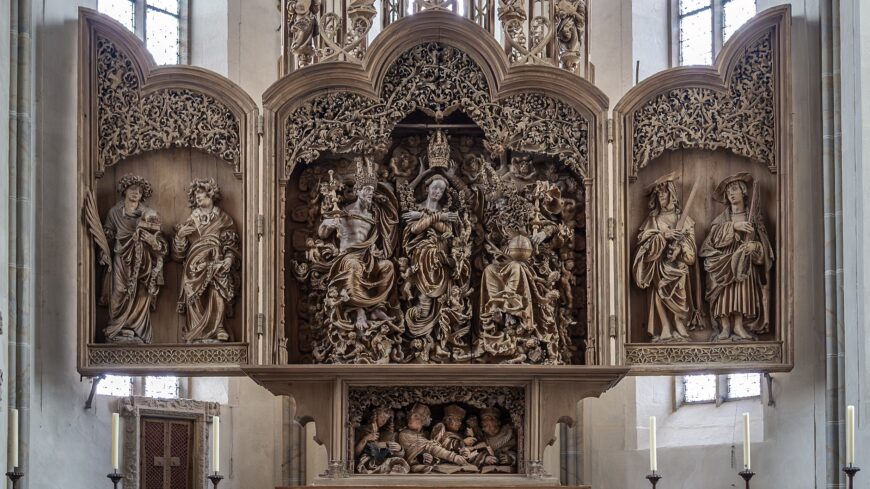

Between 1523 and 1526, the artist known as Master H.L. carved the understated yet affecting Breisach Altarpiece to adorn the high altar of the church of Saint Stephen in the city of Breisach, Germany.

Altarpieces (also called retables) may be painted, carved, or a combination of both. Master H.L. is only known to us by his initials, though art historians have speculated about his identity. His initials appear in three separate places in the altarpiece.

Altarpieces stand behind an altar and create the backdrop for the celebration of the Eucharist, the blessing and eating of the bread and wine that is the climax of public Christian worship.

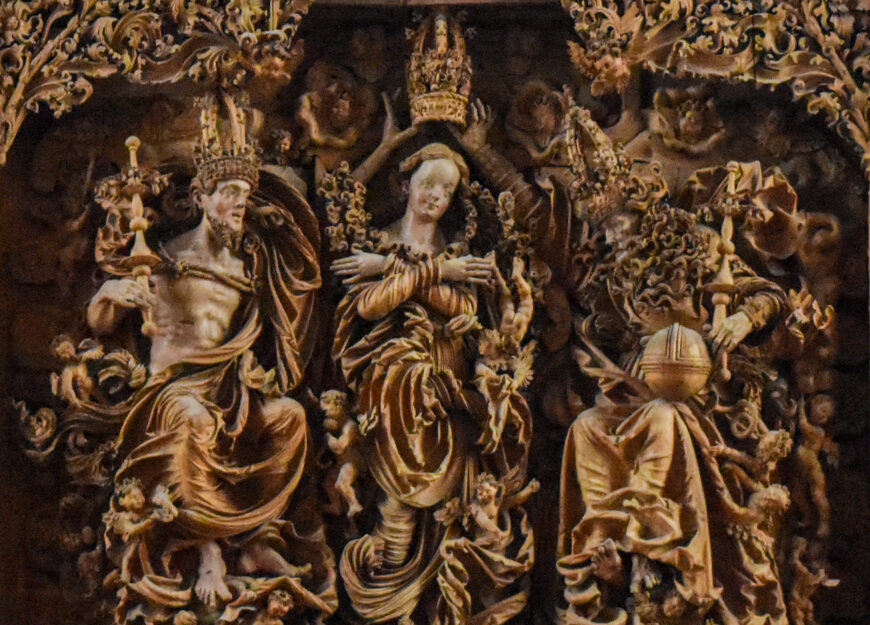

Mary (detail), center panel with the Coronation of the Virgin, Master H.L., The Breisach Altarpiece, c. 1523–26, limewood (Saint Stephan’s Cathedral, Breisach)

Master H.L. was active in an area overlapping the modern borders of Germany and France, including Colmar, Freiburg, and Strasbourg in addition to Breisach. Master H.L. was also a print maker. Like sculpture, printmaking as a technique involves carving in wood and metal and relied on line rather than color for expression.

Northern European artists of the 15th and 16th centuries often made carved altarpieces (retables). A very famous example is the colorful and shining Saint Mary’s Altar in Saint Mary’s Basilica in Kraków, Poland by the German sculptor Veit Stoss.

Unlike the lavish gold and colors of the Stoss’ altarpiece in Kraków, Master H.L. and his patrons chose a quieter mood. Like his contemporary Tilman Riemenschneider, Master H.L. stained the carved limewood a warm, earthy brown. This predominant monochrome allows the crests, waves, dips, swirls, and shadows of the carving to speak for themselves almost entirely without color, save for the delicate passages of reds around the mouths, blues around the eyes, and the alabaster faces of the figures.

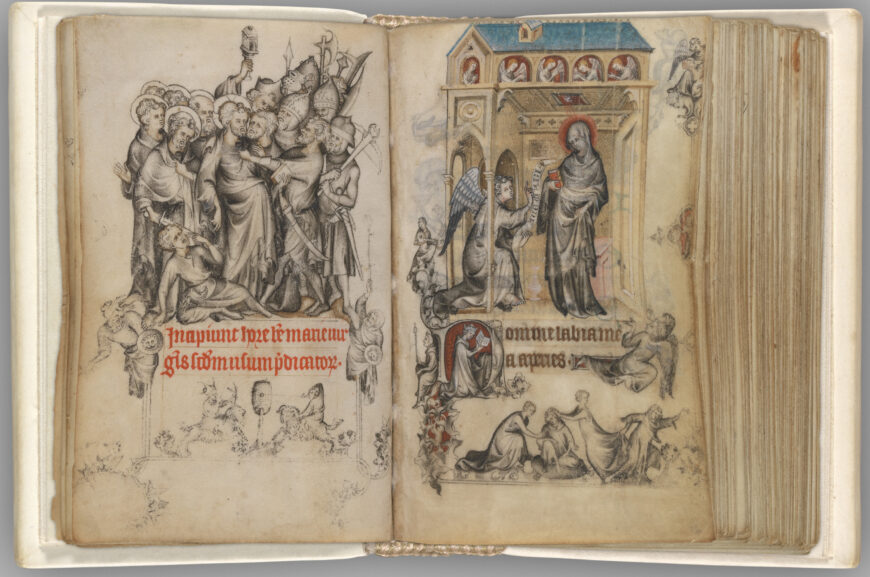

Such delicate touches of color recall a prayerbook called The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux by Jean Pucelle of 1325, painted in grisailles (shades of gray) with subtle passages of color that enliven and enhance the gray shadows and lines.

Jean Pucelle, The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France, c. 1324–28, grisaille, tempera, and ink on vellum, 9.2 x 6.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In Breisach, the restrained monochrome allows the deep carving and complex shadows to extend outward, creating a sense of figures emerging out of shadows on their own and sharing space with viewers. Flickering candlelight enlivens the figures and shadows even further.

Despite the quiet of the medium, the dancing lines and joyful subject are exuberant. The central panel displays the Coronation of the Virgin, who sits in glory in heaven, receiving a crown from God the Father to her left and the risen Christ to her right.

The Virgin herself exemplifies ideal beauty of 16th-century Northern Europe. She is a very young woman with a high forehead and long tresses. Surrounded by carved tendrils and arabesques as well as playful angels, she inclines her head to receive the crown from Christ and God the Father, looking towards the viewer rather than God or Christ. The sculptor framed her head on one side with the arms of God and on the other with the arms of Christ, while her folded arms complete the bottom length of the triangle.

In Breisach, the restrained monochrome allows the deep carving and complex shadows to extend outward, creating a sense of figures emerging out of shadows on their own and sharing space with viewers. Flickering candlelight enlivens the figures and shadows even further.

Despite the quiet of the medium, the dancing lines and joyful subject are exuberant. The central panel displays the Coronation of the Virgin, who sits is in glory in heaven, receiving a crown from God the Father to her left and the risen Christ to her right.

Center panel with the Coronation of the Virgin (detail), Master H.L., The Breisach Altarpiece, c. 1523–26, limewood (Saint Stephan’s Cathedral, Breisach)

The Virgin herself exemplifies ideal beauty of 16th-century Northern Europe. She is a very young woman with a high forehead and long tresses. Surrounded by carved tendrils and arabesques as well as playful angels, she inclines her head to receive the crown from Christ and God the Father, looking towards the viewer rather than God or Christ. The sculptor framed her head on one side with the arms of God and on the other with the arms of Christ, while her folded arms complete the bottom length of the triangle.

Left: jamb figure (detail), west portal, Notre Dame de Chartres, 12th century; right: God the Father (detail), Master H.L., The Breisach Altarpiece, c. 1523–26, limewood (Saint Stephan’s Cathedral, Breisach)

The detail of God the Father is both lush and demure. Creased skin around his eyes suggest wisdom and concentration. The thin, straight nose and sensitively formed lips are proportionate and quietly expressive. The extravagant beard, whose locks flow like long hair floating under water, flutters around the face without overwhelming it in a display of virtuoso carving and energetic line and texture. The intense bone structure and angled, thoughtful eyes recall the gaunt, inward features of Gothic sculpture, such as the 12th-century jamb figures at Chartres Cathedral.

Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (open to the Coronation of the Virgin surrounded by two panels depicting the apostles), 1516, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The subject matter and style recall the altarpiece painted by Hans Baldung Grien in nearby Freiburg. Baldung’s altarpiece is painted rather than carved, but also depicts the coronation of the Virgin surrounded by jubilant angels. Master H.L. was almost certainly familiar with and inspired by Baldung’s painting. Baldung, in turn, may have drawn inspiration from sculpted retables, as the tight composition and interweaving of figures suggests.

Wings and superstructure

The wings in Breisach depict Saints Stephen and Lawrence on the left, and the city patrons of Breisach, Saints Protaseous and Gervasius, whose relics are kept in the church, on the viewer’s right.

Left: Saints Stephan and Lawrence; right: Saints Protaseous and Gervasius, Master H.L., The Breisach Altarpiece, c. 1523–26, limewood (Saint Stephan’s Cathedral, Breisach)

The figures are dressed sumptuously, stand before a flat ground, and are surmounted by an intricate weaving of abstract leaves. The unadorned ground allows the figures to stand out as individual personalities and styles—bearded or clean shaven, baby faced or mature. The saints, blessed but less holy than the Virgin or the Trinity, are a step out of our mundane world towards the holy figures in the center.

The soaring superstructure (Aufzug or Gesprenge) that soars above the altarpiece is a tangle of vegetal lines and tendrils, with The Holy Kinship (Mary, her mother Anne, and Christ) at the top and Christ as the Man of sorrows, displaying his wounds from the Crucifixion.

Predella

The predella, the rectangular section at the bottom, depicts the four evangelists, traditionally identified as the writers of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, as life-sized busts.

Predella, Master H.L., The Breisach Altarpiece, c. 1523–26, limewood (Saint Stephan’s Cathedral, Breisach)

Each is a different age and possessed of a different personality, all seeming to bring a different perspective and attitude to the active discussion and weighty project of writing the Gospels. Their active discussion makes them look more like scholars exchanging ideas than visionaries receiving God’s word.

Jeffrey Chipps Smith (see additional resources below) rightly observes the difference between the Breisach Altarpiece and the conventions of much Italian art, where a viewers are expected to stand stock still and observe a space that opens up before them as a world seemingly contiguous with their own. In contrast, the shadows and turning attitudes of the figures within the Breisach Altarpiece practically invite the viewer to dance. To see each of the figures and enjoy the changing effects of light, the viewer must move left and right, forward and back to experience the full effect.

Choir screen

One complicating factor is the choir screen. Jacqueline Jung (see recommended sources below) proposes that choir screens organize and enliven church spaces, functioning almost cinematically.

View through the choir screen, Master H.L., The Breisach Altarpiece, c. 1523–26, limewood (Saint Stephan’s Cathedral, Breisach)

Light and shadow, figures and objects move as the viewer moves, revealing changing perspectives and fragments of the altarpiece and the rest of the space.

Choir screens divide space within a church, separating the most sacred spaces reserved for the clergy from the more workaday spaces open to the laity. Dating from the 1490s, the screen was in place when Master H.L. was designing the altarpiece. In one sense the choir screen may impede our view of the altarpiece, but on the other hand, it choreographs our dance with the object even further. The figures in Superstructure were meant to respond to the changing light coming through the screen. The Four Gospel writers are visible through central portal of the screen, and rest of the figures reveal themselves as we walk closer.

We often talk about works of art in terms of the artist’s identity; for instance, we speak of a “Michelangelo” or a “Vermeer”. We are so accustomed to this convention that it is tempting to think that works of art by anonymous masters are less worthy. We tend to forget that naming artists is a relatively recent practice. For most of human history and in most parts of the world, artists were anonymous. Though we cannot be sure about his identity, Master H.L. is no less worthy than his named contemporaries.