Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1491–1508, oil on panel, 189.5 x 120 cm (The National Gallery, London). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Left: Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1483–86, oil on panel, 199 x 122 cm (Musée du Louvre); right: Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1491–1508, oil on panel, 189.5 x 120 cm (The National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There are two versions of Leonardo‘s Virgin of the Rocks (the version in the Louvre was painted first). These two paintings are a good place to start to define the qualities of the new style of the High Renaissance. Leonardo painted both in Milan, where he had moved from Florence.

Normally when we have seen Mary and Christ (in, for example, paintings by Fra Filippo Lippi and Giotto), Mary has been enthroned as the queen of heaven. Here, in contrast, we see Mary seated on the ground. This type of representation of Mary is referred to as the Madonna of Humility.

Mary, St. John, Christ and an angel (detail), Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1491–1508, oil on panel, 189.5 x 120 cm (The National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with two Angels, c. 1460–1465, tempera on panel, 95 x 63.5 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Mary has her right arm around the infant St. John the Baptist who is making a gesture of prayer to the Christ child. The Christ child in turn blesses St. John. Mary’s left hand hovers protectively over the head of her son while an angel looks out and points to St. John. The figures are all located in a fabulous and mystical landscape with rivers that seem to lead nowhere and bizarre rock formations that recall the Dolomite mountains of northeastern Italy. In the foreground, we see carefully observed and precisely rendered plants and flowers.

We immediately notice Mary’s ideal beauty and the graceful way in which she moves, features typical of the High Renaissance.

This is the first time that an Italian renaissance artist has completely abandoned halos. Fra Filippo Lippi reduced the halo to a narrow ring around Mary’s head. Clearly the unreal, symbolic nature of the halo was antithetical to the realism of the Renaissance. It was, in a way, a necessary holdover from the Middle Ages: how else to indicate a figure’s divinity?

But Leonardo found another way to indicate divinity—by giving the figures ideal beauty and grace. After all, we would never mistake Leonardo’s group of figures for an ordinary picnic—the way the Lippi’s painting of the Madonna and Child with Angels almost looks like a family portrait. With Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks, we are clearly looking at a mystical vision of Mary, Christ, John the Baptist, and an angel in heaven.

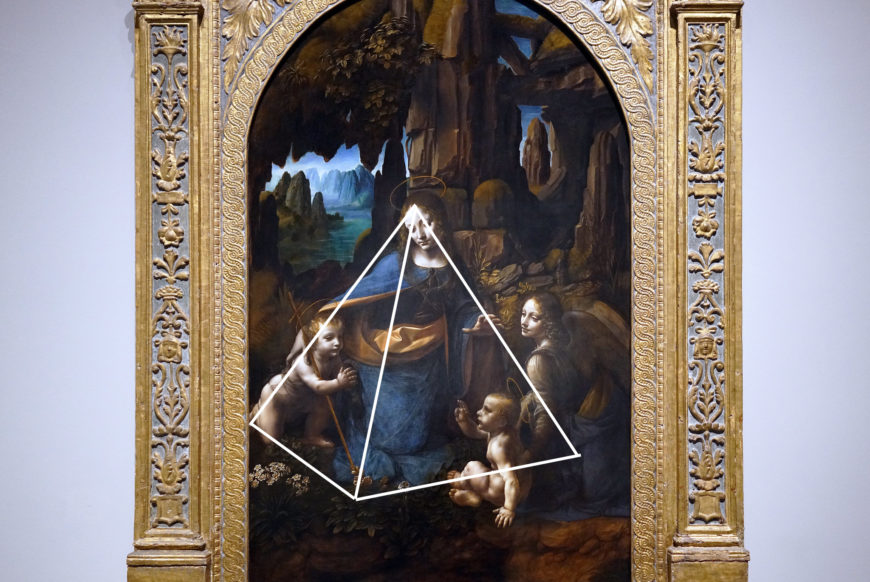

Implied pyramid, Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1483–86, oil on panel, 199 x 122 cm (The National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The unified composition

We can see that Leonardo grouped the figures together within a geometric shape of a pyramid (a pyramid instead of triangle because Leonardo is concerned with creating an illusion of space—and a pyramid is three-dimensional). He also has the figures gesturing and looking at each other. Both of these innovations serve to unify the composition. This is an important difference from paintings of the Early Renaissance where the figures often looked more separate from one another.

Left: Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ, 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Pixel8tor); right: Angels (detail), Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ, 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Pixel8tor)

Another way to think about this is to look at the angel that Leonardo painted in this work by his teacher Verrocchio. Leonardo’s angel has a more complex pose. Things that artists were just learning how to do in the Early Renaissance (like contrapposto) are now easy for the artists of the High Renaissance.

As a result, artists of the High Renaissance can do more with the body—make it more complex, more elegant, and more graceful. Similarly, the compositions of the paintings of the High Renaissance are more complex and sophisticated than the compositions of the Early Renaissance—figures interact with gestures and glances, and are often interwoven and set within the shape of a pyramid.